The Most Popular Jobs 300 Years Ago

If you were to get into a time machine and travel three centuries into the past, you would encounter some obvious differences between then and today. The 1720s had a noticeable lack of electricity (to us, anyway), while travel and communications took far more time in an era before jet engines and the Internet. Likewise, you would have perhaps been considered a bit odd if you attempted to describe a computer chip or wireless Bluetooth technology — though it's easy to imagine a young Ben Franklin listening on with interest (the Enlightenment was well underway, after all).

What people did for a living, however, might have seemed oddly familiar. Sure, some worked in what we might now consider niche jobs making wigs and fancy saddles for rich people, but there were also plenty of bakers, early pharmacists, and clothes-makers. An even closer look at these popular jobs reveals valuable information about 18th-century society, underlining what was important to many people in Europe and the American colonies and how these communities worked in a pre-industrial era.

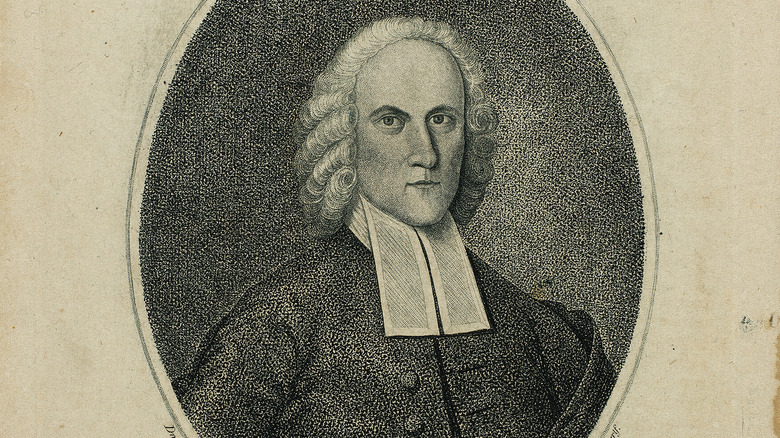

Clergy

In the early decades of the 18th century, religion was central to daily life in Europe and its colonies. With so many people trooping into and out of churches, few figures were as prominent as preachers. Though the variety of clergy and how they operated varied from community to community, it was still often a plum job. Ministers were often highly educated and established themselves as highly respected social fixtures.

Things weren't always hunky-dory for clergy, however. By the 1700s, the Enlightenment had led to increasingly secular thought, while the church began to stagnate — with dwindling congregations to show for it. Then, as the 1720s came to a close, a religious revival now known as the Great Awakening began to take root in the American colonies. One of the most prominent and controversial figures of this period was Jonathan Edwards, a New England minister whose 1741 sermon, "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," emphasized divine judgment and the innately fallen nature of humanity.

Despite Edwards' reputation (he was fired from one parish in 1750), the widespread popularity of other ministers meant that the Great Awakening was there to stay. The common messages of humanity's sin, God's forgiveness, and the highly personalized relationship with the Divine proved compelling. The Great Awakening revitalized Christianity in America and kept preachers prominent.

Tailor

In the 18th century, clothes were the products of serious labor that required workers to harvest fibers, spin them, weave that thread into cloth, and assemble the product into an outfit. Over in colonial America, just about everyone who wasn't living on the frontier needed a tailor, as they were often too busy with other tasks to make their own clothing. It got so that colonial cities were packed with tailors, while cloth was easily the most imported good in the colonies.

Tailors, who were typically men, entered the trade with a years-long apprenticeship under a more experienced tailor. In England, they would also have hoped to join the powerful tailors' guild and perhaps earn a position as a well-respected and highly-skilled cutter or finisher (as opposed to rather lowly "table monkeys" who merely sat there and sewed bits of cloth together). While urban European tailors eventually specialized in particular garments and clientele, colonial ones kept their portfolio broad and offered a wide variety of garments for everyone, from enslaved people to high-ranking elites.

Women weren't totally cut out of the profession, though they struggled to receive the same level of recognition. In late 17th-century France, seamstresses were able to form a guild of their own, though the French tailors' guild managed to get royal backing and blocked seamstresses from many competing markets. And in 18th-century England, some middle-class women accepted that they would have to sew to earn money, engaging in a genteel trade to support themselves.

Printer

The printing press likely got its start in 9th-century China, but while it was already well-established by the 1720s, there's no denying that the printed word had become very popular. Literacy figures from this time are hard to pin down, but an average of 60% of men and 40-50% of women in England were literate (with even higher rates in cities). It's likewise difficult to determine literacy rates in the American colonies, but evidence suggests that a great many colonists prized reading and patronized print shops.

That's in part because prints, newspapers, and other texts would prove pivotal in the build-up to the American Revolution. By that time, people like Paul Revere and Benjamin Franklin had already established themselves as printers and literary figures. Franklin first published while working in London as a 19-year-old printer and gained widespread acclaim for his almanac, "Poor Richard," which first came off the press in 1732.

In an 18th-century print shop, the compositor was tasked with assembling a page letter by letter and backward, all to ensure that the printed lines came out in order. Once set in a frame, the assemblage was taken over to the printing press, where another worker covered the type with ink. A sheet of paper was lowered onto the inked type by a pressman who exerted about 200 pounds of force onto the press, which they would then hold for about 15 seconds. They would repeat this throughout workdays that could easily stretch beyond 12 hours.

Coffee shop owner

Though Britain is nowadays well-known as a land of tea drinkers, another caffeinated beverage once dominated the land. Coffee shops first showed up in England in 1652 Oxford and, by the 1700s, were seemingly everywhere. Yet these places weren't serving sweetened, blended drinks, but a seriously bitter brew better regarded for its effects than its taste. Energized coffee drinkers turned coffee houses into social hubs where men could chat, debate, and make business deals. However, women were often denied entry. Despite this and other less-than-savory elements (some coffee shops had a seriously downmarket reputation), they remained popular until tea took off at the end of the 18th century.

Coffee shop proprietors also set down stakes in colonial America, including in the old capital of Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia, where R. Charlton's was a popular place for men looking to take part in the community's intellectual life. Archaeologists working at the site have even uncovered the remains of an articulated skeleton held together by wire, which may have been used in anatomy talks held inside the shop.

Woodworker

A sufficiently skilled woodworker would have plenty of jobs in a community, given that 18th-century people needed not only wood structures to live and work in, but wood barrels, wheels, furniture, instruments, and more.

In cities, carpenters worked in separate yards, as they needed plenty of space to store and shape timber. While they were often busy assembling the frame of a building, joiners would focus on more detailed features like doors, shutters, and cupboards. Wheelwrights could be found doing even more specialized work, employing their skills to piece together wood and iron bands to craft tough, well-balanced wheels that could handle the unpaved roads of many settlements. Without someone to make and repair wheels, it's easy to see how travel and commerce could grind to a halt in the 18th century.

But, even with all of that woodworking going on, there's one other woodworker who might have won the most important spot in some places: the cooper. In a time before cardboard boxes and metal shipping containers, the wood barrels and casks crafted by coopers were needed to hold important commodities for shipping and storage. A carefully crafted cask made by a skilled cooper could store food, allow other workers to make food (like in a butter churn), age wine, or carry all-important trade goods like gunpowder and tobacco from one place to another.

Alewife

It may seem like women were shut out of many jobs in the 18th century. The reality is more complex, especially when you consider many had families to feed and bills to pay. Women, usually under the social and legal control of a father or husband, often took part in family enterprises, whether it was running a farm or a business. They were also expected to take on the labor of caring for home and family. Women, especially unmarried or widowed ones, could also run their own businesses.

In the 18th century, one of the more popular enterprises for European and colonial women was brewing. Though modern brewing is still male-dominated, its history shows that it was very much women's work. In Europe, medieval and early modern women set up small brewing operations that could earn money while still caring for their home and its occupants. The work sprang out of the standard housewife task of brewing low-alcohol ale for the family. Any surplus could be sold by the woman of the house, who came to be known as an alewife. Some 17th-century women were even encouraged to move to the colonies because of their brewing skills.

By the 1700s, women also ran more official pubs. Yet, alewives had been pinned with a shady reputation that claimed they were dirty, immoral folk who might even be witches. Soon, this popular job would be overtaken by increasingly strict laws that allowed male brewers to push women out of the field.

Saddler

Though horses were one of the ways 18th-century people got around, the reality is that these expensive animals required not only land and food, but spendy accouterments like bridles, saddles, plows, and other tack. So, whether you were in Europe or the North American colonies during this era, you wouldn't have been guaranteed access to a horse. If someone owned a horse, chances were that they were financially comfortable. That was all the more true in the American colonies, where horses were initially spendy imports that had to make it through a long transatlantic voyage. And, as with so many occupations of the rich both then and now, you could make a pretty penny if you were willing to cater to upper-class tastes.

Enter the saddler. In the 1700s, these people were responsible for crafting not just saddles, but many of the other leather-based objects required to ride horses, like bridles and harnesses. Becoming a saddler required a long apprenticeship and specialized tools that allowed one to carefully cut and assemble leather pieces. Saddlers also had to develop a finely-tuned understanding of their materials, as different kinds of leather perform in unique ways.

Establishing oneself as a master saddler also meant creating one's own unique patterns, which then had to be carefully guarded lest another saddler steal their intellectual property and take over a rival's client base. Saddlers also did quite a lot of repair work, so building good relationships with customers could mean lucrative repeat business.

Wigmaker

Often known as perukes, expensive wigs that were dusted with white powder for a refined look first gained popularity in the 17th century, when Louis XIV of France and Charles II of England adopted them to mask graying locks and receding hairlines. Soon, thanks to court-based trendsetters, the wig became a symbol of high rank and deep pockets. In the early American colonies, some notables still wore perukes, while others (like the redheaded George Washington) powdered their hair white to mimic the look. But as the Enlightenment and a couple of revolutions in America and France shook things up, the hoity-toity powdered wig came to be seen as an old-fashioned symbol of class inequality. By the end of the century, the wig was done for.

But when the peruke was in its heyday, a wigmaker with the right clientele could do well. It helped that they also typically worked as barbers and hairdressers even for the wig-free set. Wigs also took a lot of work and time to craft. A group of wigmakers and curators at Colonial Williamsburg found that out for themselves when they created a reproduction of an 18th-century wig used by Boston merchant Henry Bromfield (which was stored in a coconut shell). The project took about 145 hours of labor and required preparing horsehair by curling and boiling it to set the shape. Then wigmakers wove, stitched, and knotted the wig by hand (a dizzying 45 hours was required for just the knotting).

Tavern proprietor

While some communities might have made their way without saddlers, wigmakers, or printers, few would have felt complete without a tavern. In colonial America, these establishments were so important that, in 1656, Massachusetts lawmakers threatened tavern-less towns with a fine. It wasn't just that these spots served alcohol; taverns also acted as important social hubs, official meeting places, ad-hoc courthouses, and typically safe havens for travelers. Taverns may have also played a significant role in the lead-up to the American Revolution, as they became full of open political debate.

Popular as their establishments were, tavern keepers would have had quite a lot to handle. They were required to sell decent products, as some keepers were caught selling adulterated or expired booze in an attempt to cut expenses. They also had to make sure their tavern was a fun place but had to navigate local laws and social attitudes about less-than-savory activities like gambling and dancing.

Still, even if upper-crust folks or prudish types steered clear of some taverns, it's clear that these places were central in many communities, especially considering the tax breaks and practically free land granted to some proprietors. What's more, taverns provided a potentially life-saving income for women at a time when many were shut out of more lucrative work. In fact, colonial American taverns were more often run by a woman than a man. A woman might even inherit the business (and its already existing license) from a deceased husband or her own mother.

Blacksmith

If you lived in the 1700s and needed something made out of metal, there was really only one person who could help you: the blacksmith. Just about any metal object had to be crafted by one, from nails and sewing needles to plows. Horses need new shoes? Blacksmith. In the market for a cooking pot? Blacksmith. Want your doors and windows to hinge and latch properly? Call the blacksmith. And if you wanted a set of armor (or even needed a blacksmith to come along on your military campaign for running repairs), then you had better be sure you were nice to the blacksmith you hired.

It would take the 19th-century Industrial Revolution to unseat the blacksmith as a critical member of a community. Until then, they were valued as key craftspeople with a high level of skill and a tolerance for the punishing conditions of a blacksmith's shop. Blacksmiths not only had to carefully observe the color of the metal to determine when it was at the correct heat, but they also had to keep everything as clean as possible to ensure strong welds and resilient blades. At the heart of the shop was the forge, which contained a relatively small but still quite hot fire. Blacksmiths and their assistants were hard at work despite the heat, maintaining bellows that brought just the right amount of air to feed the fire while hauling sometimes large pieces of metal and heavy hammers to shape a piece.

Baker

While some modern people may maintain the fantasy of living on a self-sufficient homestead and chowing down on a fresh loaf of sourdough bread, real 18th-century life left little time for baking. Unless you were the baker, of course. While some home cooks did set aside time for the labor-intensive process of heating an oven, assembling dough, and baking it (without modern timers or thermometers), bakers also did well selling finished products to time-scrapped shoppers.

Bakeries, with their large ovens, could get seriously hot. As a result, bakers sometimes stripped down to the bare minimum of clothing, though they at least wore head coverings meant to keep the dough clean. They also worked odd hours, rising early much like modern bakers to get goods ready for the day.

While the baker was an important person in many bustling settlements, they were necessarily appreciated. Wages were highly variable and records from mid- to late-18th century France show that payment for bakers was stagnating. Given the tough working environment, demand for high skill, and disappointing payment, perhaps it's no wonder that controversial bakers and bread shortages were part of the lead-up to the French Revolution. Bakers might also be scrutinized more than other workers, as they were known to mess with ingredients and weights in an attempt to shortchange customers. Reportedly, this is where the tradition of a baker's dozen (13 instead of 12 baked goods) originated, in an attempt to level things out.

Apothecary

When an 18th-century person grew ill and had the means to get trained help, they were likely to visit an apothecary. These medical professionals were part of a three-part European-style healthcare system that also included surgeons and physicians. Where the latter two were more often found diagnosing and treating patients, apothecaries acted like early pharmacists, mixing and dispensing medications from a dedicated retail shop. In the American colonies, apothecaries could be few and far between, so physicians sometimes took on the task of handing out their own medications. Apothecaries did operate in some colonial cities, though they sometimes garnered a less-than-wholesome reputation for peddling quack remedies. In Europe, however, apothecaries were a far more organized group that sometimes even had regulatory bodies monitoring how medicines were created and distributed.

Apothecary shops relied on marketing, with a distinct look that included shelves full of glass and ceramic jars containing the necessary ingredients. The apothecaries themselves would have also compounded many remedies in their shop, oftentimes mixing and crushing ingredients with the mortar and pestle that's still on some modern pharmacy logos. In the colonies, powdered medicines were the norm, though some liquids and pills could be had at the local apothecary shop. Some might have been expensive imports, sold alongside other goods like tobacco and toothbrushes not unlike a modern convenience store.