The Untold Truth Of J.R.R. Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien was truly "the father of modern fantasy." He may not have invented dragons, but he's the guy who made them cool. Without Tolkien, Voldemort would probably have a nose and Daenerys Targaryen would have to walk everywhere. Just about every writer of high fantasy who has ever put a word on a page has either been deeply influenced by J.R.R. Tolkien or has had to actively work to keep from being deeply influenced by him. Either way, that's pretty high praise.

But most of us know more about Frodo and Bilbo than we do about the man who created them. As it turns out, J.R.R. Tolkien wasn't just an inventor of fantastic worlds, beloved characters, and creatures both horrifying and adorable, he was also a linguistic genius and a hopeless romantic. Also, no matter what anyone tries to tell you, he clearly had a weird thing about spiders.

Tolkien had an unfortunate childhood, and not just because he had four names

The most pressing question about J.R.R. Tolkien is this one: What's the deal with the three initials, dude? That's just weird, and also, as an author name it doesn't exactly roll off the tongue, it just sort of falls awkwardly out of the mouth. But alas, Tolkien actually did have three given names, so he's not totally responsible for the fact that we all sound really stupid when we say "J.R.R. Tolkien" out loud. He was born John Ronald Reuel Tolkien and as a child was called Ronald, probably because everyone would have gotten really tired of calling him "J.R.R."

According to Biography, Tolkien was born in Bloemfontein, South Africa, in 1892. When he was still pretty small, his mother moved him and his younger brother to Sarehole in Birmingham, England. His father stayed behind in South Africa and later died from rheumatic fever when Tolkien was 4 years old. Then his mother died, too, when he was just 12, so he spent his teenage years as an orphan, living with a relative and in boarding homes, before he was finally taken under the guardianship of a Catholic priest named Father Francis. It's impossible to say how much of that difficult childhood informed his writing, but Tolkien stories do tend to be somewhat dark, so it's sadly possible that Tolkien wouldn't have been the same writer if he'd had a sunny childhood totally free of tragedy and loss.

Why the giant spiders, though, J.R.R.? Just why?

In the Lord of the Rings trilogy, Frodo nearly gets eaten by Shelob, the demon-spider who lives in "the pass of the spider," somewhere between Mordor and that one dark corner of your garage you've been avoiding for the last decade. And that's not the only Tolkien story that features arachnid horror — Bilbo also encounters a forest full of spiders in The Hobbit. So clearly, Tolkien had a thing about spiders. Why?

Well, forgetting the fact that 99 percent of the human population has a thing about spiders, Tolkien's thing may have stemmed from an encounter he had as a small child living in South Africa. According to Tor.com, J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography says Tolkien was bitten by a tarantula while learning to walk. Tolkien, though, said he had little memory of the event and actually claimed to like spiders, to the point where he would rescue them from the tub rather than letting them go down the drain like a normal, non-crazy person.

So he poo-pooed the idea that that long-ago spider bite had anything to do with Shelob and instead blamed his son Michael. Michael was evidently terrified of spiders, so Tolkien did what any good father would do — he wrote the world's scariest spider-attack scene with the sole intention of scaring the crap out of the unfortunate little thing. So now, we all get to have nightmares about giant spiders courtesy of Michael Tolkien. Thanks, kid.

The name Bag End did not just come from his weird imagination

The name "Bag End" seems really silly and totally made up. It's sort of vaguely similar to the name of our hero, "Baggins," (which by the way means "packed lunch" in the Yorkshire dialect) and we get the impression that the word "end" refers to a final destination, the place the hobbits plan to return to when they're done battling giant spiders and weird scrawny bald dudes who overuse the word "precious." But a bag end is, quite frankly, the bottom of a brown paper sack, so what the heck.

Amazingly, Tolkien did not make up the name "Bag End." According to the Tolkien Library, he borrowed it from his Aunt Jane, who owned a farm in Dormston, Worcestershire, England. The farm was not only called Bag End, it had always been called Bag End, maybe even since Anglo-Saxon times.

There are some Tolkien scholars who think he adopted more than just the name and that some of the farm's features also showed up in his description of the fictional Bag End. But Tolkien himself never had much to say about the real Bag End besides saying it was "at the end of a lane leading to it and no further," so it's really impossible to say how much inspiration he took from the place.

Homeschooling is the father of quirky

If you've ever thought that homeschooled kids are just weird, well, we won't say you're totally wrong. Homeschooling does kind of go hand-in-hand with quirky, but quirky isn't necessarily a bad thing, and you kind of do have to have a quirky mind to come up with things like barrow-wights, hobbits, and the eternally creepy "watcher in the water."

Tolkien and his younger brother were both homeschooled, but it wasn't like the sleep until 10 a.m. and watch cartoons sort of homeschooling. Tolkien's mother taught her sons stuff that most modern mothers don't learn until college, like Latin and botany. By the age of 4, Tolkien could read, and Biographics says he could write not long after that. He also had a talent for drawing, even as a small child — a talent he put to good use when he grew up and did all of the original illustrations for The Hobbit. So maybe it's true that homeschooled kids are a little quirky, but would we want The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings to be not-quirky? No, we would not. Although both could do with fewer giant spiders.

He married his childhood sweetheart

When Tolkien was 16, he befriended a 19-year-old neighbor named Edith. The two were fond of causing trouble, although in those days trouble evidently wasn't so much hiding in the locker room with a cigarette or stealing liquor from the corner market as it was sitting in a rooftop tea room and throwing sugar lumps into the hats of passers-by.

According to Biographics, Tolkien's guardian, Father Francis, thought the relationship between Tolkien and Edith was scandalously inappropriate, not because of the weird sugar lumps thing but because Edith was (gasp!) a Protestant. So he forbade Tolkien from seeing her again until he turned 21 years old. Tolkien dutifully obeyed, and the night before his 21st birthday he wrote Edith a letter containing a marriage proposal.

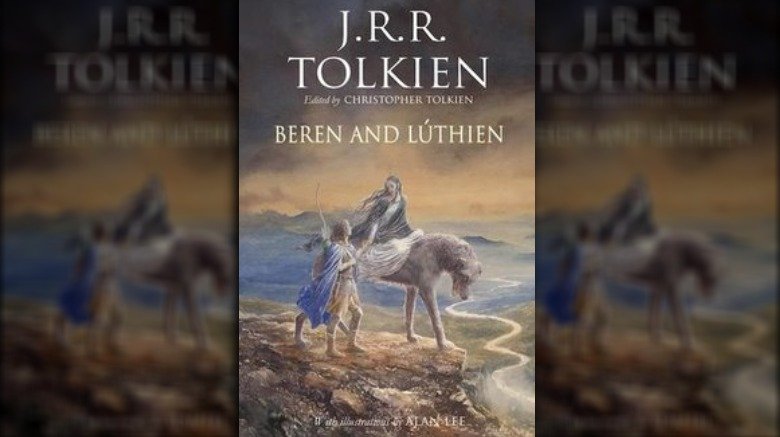

The marriage produced four children and at least two memorable characters. Tolkien's story of Beren and Luthien, a mortal who fell in love with the daughter of the Elven King after watching her dance in a glade, was inspired by a real-life moment in which Tolkien watched Edith dance in a clearing full of white hemlock flowers. So not only was Tolkien hopelessly weird about spiders, he was also a hopeless romantic. Aww.

Tolkien could talk to people who have been dead 2,000 years

While most kids are still learning how to say "poopy diaper," Tolkien could say "poopy diaper" in a dozen languages. Okay we're exaggerating, obviously, but even as a child Tolkien had a talent for languages and a great interest in learning them. Biographics called Tolkien "an exceptional student who was capable of easily mastering ancient and modern languages." He knew four languages by the time he was a teenager, and as an adult he could speak Swedish, Norwegian, Danish, German, Dutch, French, Spanish, Italian, Welsh, Russian, and Finnish. He wasn't content with just languages that you could use to speak to actual, living people, though. He also knew a whole bunch of ancient languages, including Old Norse, Old English, Middle English, and medieval Welsh.

He didn't literally talk to 2,000-year-old corpses, but if someone found a Viking shield-maiden frozen in a block of ice somewhere in Norway and then thawed her out with a hair dryer, Tolkien could have found out her name and favorite thing to have for breakfast. That sounds an awful lot like a superpower.

Speaking a ridiculous number of languages wasn't quite fulfilling enough

When Tolkien wasn't learning how to speak languages, he was inventing languages. In fact according to Hobbits, Elves and Wizards: The Wonders and Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings," Tolkien had already pulled a couple brand new languages right out of his butt before he'd even become a teenager, and he created more than a dozen languages over the course of his lifetime.

These weren't just some cute pig-latiny sorts of languages, either, where you just swap in one word for another but the syntax stays pretty much the same. They were real languages with unique and complex syntax, morphology, and phonology. His first attempt at a language was called Naffarin — it was heavily based on Spanish but with its own grammatical rules.

Creating a whole new language isn't something you can do in an afternoon, either. Tolkien had a whole system that encompassed not just the "modern" version of his invented language, but its historical context. He designed alphabets, too, which just seems so mind-bogglingly complex that it's hard to fathom how the dude even found time to write horrifying stories about giant hobbit-eating spiders.

What else does a super-duper word nerd do?

So if you've ever wondered who wrote the dictionary, it was Tolkien. Tolkien totally wrote the dictionary.

Not the whole dictionary, but between 1919 and 1920, the Oxford English Dictionary itself says he was on staff and working on the words at the beginning of the letter W. His contributions to the dictionary include definitions of "waggle," both the noun and the verb. He also worked on "walnut," "walrus," and "wampum," because editors felt those words had "particularly difficult etymologies" and therefore needed someone skilled in word wizardry to do them justice.

As you might expect from someone who is so clearly obsessed with words, Tolkien took his responsibilities very seriously. In fact, there's evidence he was still pondering all the etymologies of "walrus" years after he was no longer working for the Oxford Dictionary — one of his notebooks contains several pages on the subject. That's dedication.

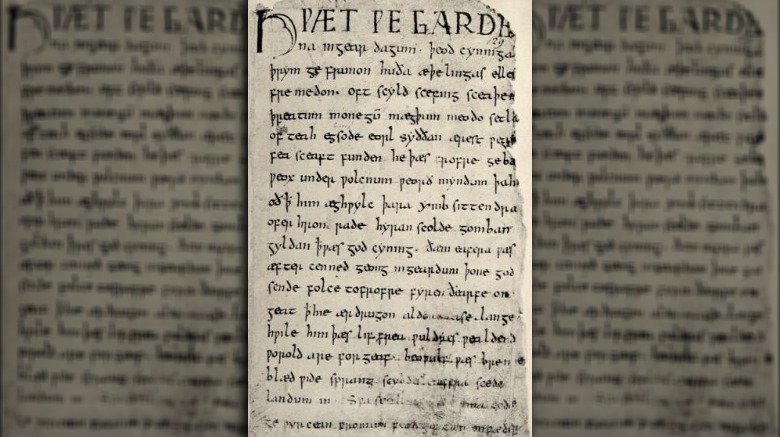

He translated Beowulf but never intended for his translation to be published

We've all read Beowulf, of course. Just kidding. Almost no one has read Beowulf, with the exception of people who enjoy especially torturous English classes and those who were homeschooled in the early 20th century.

Tolkien read Beowulf, though. He not only read it, he also called it "the greatest of the surviving works of ancient English poetic art," and because he wasn't already busy enough with all the language-inventing he was doing, he also wrote his own translation of it.

According to the New York Times, Tolkien was initially against the idea of translating the original Old English into modern English — he wondered if it would be an "abuse" to turn the famous poem into "plain prose." And he never really changed that view since he expressed dissatisfaction at his translation and then basically just stuck it in a drawer or something, where it remained for 88 years until his son Christopher dusted it off and submitted it for publication in 2014.

It's fun to note that Tolkien actually borrowed material from the thousand-year-old manuscript — that scene where Bilbo steals from the dragon Smaug was practically lifted right off the pages of Beowulf. So we're all very grateful he read Beowulf, even though we wouldn't wish it on most other human beings.

Tolkien wrote the first line of the Hobbit while grading papers

Once upon a time, J.R.R. Tolkien was totally bored. It was the 1930s, and he was working as a Professor of Anglo-Saxon (Old English) at Oxford University, and like all college professors, part of his job was to grade the super-boring work of his students. Now, just imagine how dull that work would have to be to bore someone like Tolkien, who could evidently get through Beowulf without nodding off. Anyway, according to the Independent he did get bored and so he put down his work for a little while and got out a blank sheet of paper. On the paper he wrote the words, "In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit."

That was the genesis of one of the most beloved children's stories of all time, a novel that has been continuously in print ever since its original publication date in 1937. It was an instant success, too — Allen & Unwin printed an initial run of 1,500 copies, which sold out within three months.

The Hobbit we know today is actually a revision of that first manuscript — Tolkien rewrote the second edition so it would be a better companion to its follow-up The Lord of the Rings. But it all started with a bunch of really boring coursework at Oxford University.

Tolkien took inspiration from real places and things

Tolkien's Middle-earth is pure fantasy, but like all authors he drew inspiration from the things and places he encountered in his life. The Independent says the One Ring at the center of the Lord of the Rings trilogy was based on an anecdote Tolkien once heard about a cursed ring that was found near the ruins of a Roman temple. Bilbo's home, The Shire, was based on Tolkien's childhood home in Sarehole, England. In fact the Sarehole Mill was a particular source of inspiration to Tolkien — in The Hobbit, Tolkien describes Bilbo "running as fast as his furry feet could carry him down the lane, past the great Mill, across The Water and then on for a mile or more."

If you're ever inspired to go on a worldwide tour of the places that appear (at least in spirit) in Tolkien's novels, you will also need to visit the Malvern Hills in the English counties of Worcestershire, Herefordshire, and Gloucestershire, which were the inspiration for Rohan and Gondor. Rivendell was inspired by the Swiss Alps, and the Two Towers themselves are echoes of Perrett's Folly and the Waterworks Tower in Edgbaston, in Birmingham, England.

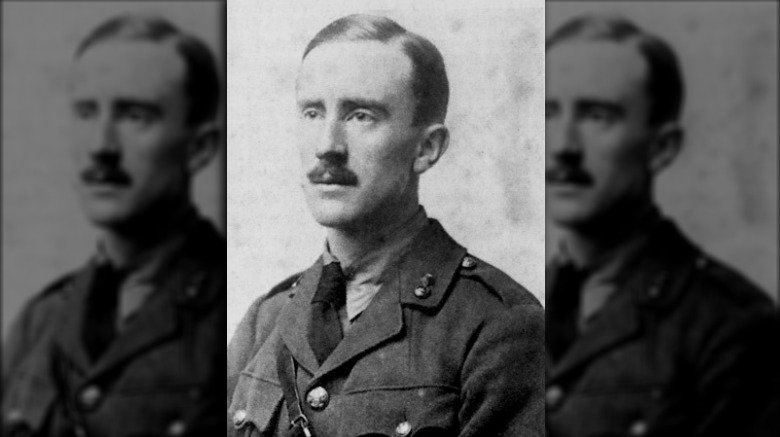

Tolkien experienced the horrors of war firsthand

Tolkien always denied that he'd been influenced by his time in the trenches during World War I, but it's hard not to believe that the Battle of the Five Armies was at least subconsciously influenced by his own personal experiences at the Battle of the Somme in 1916. In a letter Tolkien wrote in 1960, he did admit that he might have drawn from the landscape of Northern France after the Battle of Somme for his portrayal of the Dead Marshes, but he seemed reluctant to take it any further than that.

There's no doubt, though, that Tolkien was affected by the Great War. According to The Shell-shocked Hobbit: The First World War and Tolkien's Trauma of the Ring, he spent months in and out of the trenches and managed to avoid being wounded, but he did end up with "trench fever," which was caused by bacteria spread via a body louse, which you probably didn't even know was a thing since most people now wash themselves daily and are therefore not prone to body louse infestation like soldiers who live in muddy trenches are. Anyway, trench fever finally got Tolkien sent home, but many of his friends died and no one can live through war without being changed.

Tolkien totally owned the Nazis in a letter

The Hobbit was a runaway success, as we all know, and whenever anything is a runaway success there are people all over the world who want to get on board. According to Newsweek, a publisher in Berlin wrote to Tolkien to ask about printing a German translation of The Hobbit. In the letter, the publisher explained that they really wanted to print The Hobbit for sale in Germany, but before they could do that Tolkien would have to prove he had "Aryan descent."

You'll be glad to hear that Tolkien was not only disgusted by the request, he told his publisher that he was inclined to "let a German translation go hang." And instead of just leaving it there, he actually wrote back.

"I regret that I am not clear as to what you intend by arisch. I am not of Aryan extraction: that is Indo-Iranian; as far as I am aware none of my ancestors spoke Hindustani, Persian, Gypsy, or any related dialects. But if I am to understand that you are enquiring whether I am of Jewish origin, I can only reply that I regret that I appear to have no ancestors of that gifted people."

Ha. Suck on that, Nazi scum.