What The Iconic Copacabana Nightclub Was Really Like

For three decades, the original Copacabana cabaret and nightclub in New York was one of the hottest clubs in the city, if not the entire world. The club originally opened in 1940 in the basement of a hotel on the city's 60th Street, and it quickly made an impact on the local residents. Over the years, the Copacabana played host to some of the biggest names in show business, such as heavyweight crooners like Frank Sinatra, Paul Anka, Tony Bennett, and Nat King Cole.

The original cabaret also inspired several works of art, including the 1947 Groucho Marx film "Copacabana," the Barry Manilow song "Copacabana (At the Copa)," and the subsequent musical, "Copacabana." The initial run of the Copacabana came to an end in 1973, following the death of longtime manager Jules Podell. New owners including John Juliano reopened the club in 1976, but they turned the downstairs into a disco, a true reflection of the decade, and the original spirit of the Copacabana was gone.

These days, Juliano's Copacabana nightclub — now open on 51st Street in New York City – is nothing like the cabaret that used to dominate 60th Street from the 1940s–1970s, though it does preserve the name from extinction. While the spirit and feeling of the original Copacabana might be long gone, this is what it was really like back in its golden age.

The theme was originally Latin and tropically inspired

When the Copacabana first opened the week of October 27, 1940, patrons were greeted by Latin and tropically themed decor. The vision was courtesy of the club's owner Monte Proser, who tapped his friend Clark Robinson to do the decorating and designing (according to Mickey Podell-Raber in "The Copa: Jules Podell and the Hottest Club North of Havana"). The bar stools were velvet, as was the VIP section, there were tiers of palm trees everywhere, and patrons were made to feel as if they were in Brazil — undoubtedly a throwback to inspiration for the club's moniker, the massive resort of the same name in Rio De Janeiro.

The entertainment for the opening week was Pancho's and Fausto Curbello's Orchestras, and other entertainers included Latin acts Ramon & Renita, Juanita Juarez, and Fernando Alvarez (via The New York Times). Shows would go into the very early hours of the morning, with the latest beginning at 2 a.m., and the entrance fee was only $2, except on holidays and Saturdays, when it was $3.

The club also hosted benefits, like the Family Portrait Fashion Tableaux in December 1940, where instead of charging money, customers had to bring "packages of rummage" that could be resold at a thrift shop run by charitable organizations (via The New York Times). Another early Copa performer was the vaudeville comedienne and performer Sophie Tucker, who headlined the club in January 1943 (via The New York Times).

It was not open to Black patrons at first

When the Copacabana first opened, they did not admit Black patrons. At the time, segregation was still legal in America, and it would be years before famous court cases like Brown v. The Board of Education or the Civil Rights Act of 1964 would legally end racism, so the club was able to get away with it.

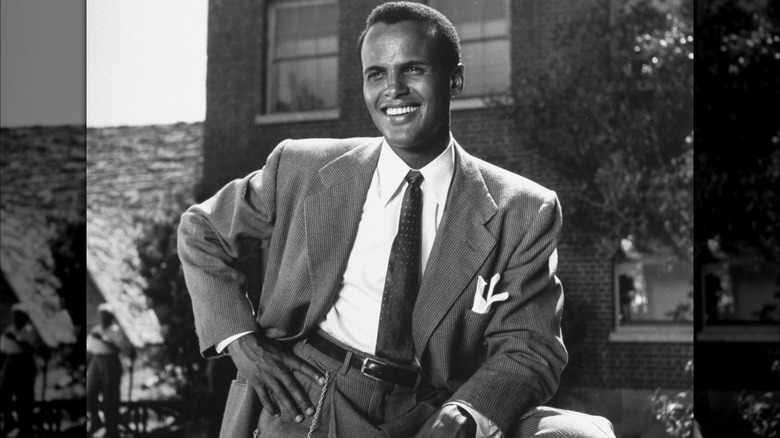

One unfortunate victim of the racist policy was Black singer, activist, and Navy veteran Harry Belafonte (via the Indiana Historical Bureau). In 1944, while on active duty, Belafonte tried to visit, but the club would not let him enter due to his skin color. Even Black performers like Nat King Cole had to use the service entrance and could not enter in the front. The discriminatory policy was in effect for years, and did not change until legendary singer Frank Sinatra threatened to stop performing (via "The Copa").

It's unclear when, but at some point Sinatra was scheduled to sing and wanted his friends Sammy Davis Jr. and Buddy Rich to attend, but the club denied them entry. Sinatra personally talked to manager Jules Podell and insisted that they be let in and treated with class, which led to the policy's end. Eventually, Black performers, including Davis, would regularly perform and even headline the club, and he and Podell became friends. Belafonte later refused a performance contract from the club over the 1944 incident, though he would return as a patron.

The Copa had a heavy mob presence

On paper, New York entrepreneur Monte Proser was the man behind the Copacabana. As someone who owned several clubs around the country at the time, including others in New York, it did not seem to be anything out of the ordinary. However, while Proser appeared to be the one in charge, in reality, the Italian-American mob was largely backing its operations.

In particular, Frank Costello (pictured above) of the Genovese crime family was the big cheese of the operation at the Copa in the club's early years. As former Copa Girl Harriet Wright wrote in her autobiography "I'd Do It Again: A Memoir," this meant that there were often a lot of "wise" guys at the club. Most of them were respectable and came across as ordinary people, though they had reputations for spending lots of money, especially on the girls. Alleged patrons included mob assassins Albert Anastasia and notorious gangster Joe Adonis, the former Brooklyn Public Enemy No. 1, who would later be sentenced to prison.

However, the mob presence eventually caught the eye of the authorities, who threatened to shutter the establishment after an investigation into Costello's secret dealings with the club. Authorities put the Copacabana on "probation" in October 1944, and the club "completely terminated" Costello from the business (via The New York Times). Yet, in reality he still pulled the strings until 1957, and patrons were undoubtedly aware of the huge mafia presence.

New acts performed in the summer

When customers went to the Copacabana, usually they could expect to see some of the biggest names in entertainment. Yet, when things were not quite as busy during the summer offseason, the manager Jules Podell would branch out and find new talent. The regular performers would be out of town doing tours and making other appearances, leaving the Copa bereft of their normal stable of acts. However, this could also benefit the newer acts at the club, as the lack of Broadway shows would sometimes mean more celebrities in New York would be free to show up.

As Mary Wilson of The Supremes wrote in her autobiography "Dreamgirl: My Life as A Supreme," she got her first opportunity to play the Copa in the summer of 1965. Podell booked The Supremes, and it ended up being a huge success for them. The Supremes played at the Copa for three weeks that summer, also recording their famous live album "The Supremes at the Copa."

The highest-paid acts at the Copa made as much as $20,000 a week in the 1960s, though probably not during the offseason. On the other hand, when The Supremes first played, their sum was substantially less at $2,750 — which didn't even cover the bar tab for all of the Motown guests in attendance. Still, it was such a thrill and honor to play the venue that the performers didn't mind, even if management may have.

The Copa Girls

Undoubtedly, for many Copacabana patrons, the world-famous Copa Girls were one of the biggest attractions, and today, they are one of its greatest legacies. Manager Jules Podell first introduced the Copa Girls in 1941, just after the Copa opened, and they were staples of the club for 28 years until he got rid of them in 1969. A 1942 profile of them in Life magazine called them "the most beautiful showgirls currently in New York," and was extremely laudatory of their beauty, dancing skills, and poise.

Most of the Copa Girls were relatively young, with the average age being just 20 years old, and were thus barely out of high school when they started dancing. In 1942, the girls made around $70 a week, which was actually pretty good considering the federal minimum wage at the same time was just 30-40 cents an hour. They performed three shows a night, seven days a week, though they largely had the daytime off, with their performances mostly coming after dark.

According to Harriet Wright in "I'd Do It Again," the first of the three shows started at 8 o'clock, with others happening at midnight and 2 a.m., and the girls sometimes had time to go on dates in between performances. At first, there were six Copa Girls, but they added a seventh in 1942, when the producer could not decide between two twins. By the time they stopped in 1969, there were 28 chorus girls.

There was incredible Chinese food

For Copacabana patrons, the food was almost as good as the entertainment. Yet, surprisingly, the best food on the menu was not tenderloins or pasta, as you might expect from a restaurant owned by the Italian-American mob, but was actually, of all things, Chinese food. Amidst the mobsters, palm trees, and Brazilian-themed decor, the best dishes were things like chop suey, chow mein, and moo goo gai pan.

In 1949, Robert W. Dana wrote about the Copacabana's kitchen, where he gushed as much about the quality of the dishes as he did about the efficiency and cleanliness of the staff (per "Food Is Tops, Too At the Copacabana"). The club's manager, Jules Podell (pictured above), ran the kitchen, and he employed a team of 20 chefs to make everything; 15 for the French cuisine and five for the Chinese fare. According to a menu from the 1940s, the Copa had a specific part of the kitchen dedicated just to making the Chinese food, and all of the chefs were from China (via Vintage Menu Art).

In addition to the Chinese dishes, the rest of the menu was mainly French-inspired, including things like lemon sole Breteuil and filet mignon. The club also had an extensive liquor list, with imported Red and White Bordeaux, Dom Perignon, and Magnum's vintage champagne at $38 a bottle. Suffice to say, if you went to the Copacabana, you could expect quite the culinary experience.

The high school prom scene

Typically, the Copacabana catered to an older and more mature crowd of clientele, but that was not always the case. In fact, every year during prom season, the Copacabana hosted scores of teenagers celebrating the most prestigious of their high school dances. The practice dated back to at least the early 1960s, and the manager of the club, Jules Podell, would hire specific performers that would appeal to the kids, like Chubby Checker — who his daughter personally requested (via "The Copa"). Another popular draw was Paul Anka, as well as the comedian Rip Taylor.

When asked, Taylor said he had to moderate some of his material from what he would usually say to adult audiences, but seemed to still enjoy his experience entertaining the students. Tony Bennett also performed for many high school proms at the Copacabana, and said that it was during the busy season for the venue, which would have been just before the summer lull took over. One high schooler who attended an after-prom party at the Copacabana was the legendary singer Barry Manilow, who saw Bobby Darin perform.

The practice was not just limited to locals, and students from throughout the New York and New Jersey areas would come to have some fun at the Copa. As of 2024, the reopened Copacabana is still a hot place for after-prom parties in its new location in Times Square, though the parties are obviously much different today.

The biggest stars performed

In order to keep the money flowing and customers coming back, the Copacabana had the most high-profile singers and entertainers performing. To name just a few of the stars to have worked the Copa, there was Frank Sinatra, Sam Cooke (pictured above at the Copa), the Temptations, Wayne Newton, Louis Prima, and countless others. Yet, while the entertainers included some of the most prolific in show business history, few, if any, could hold a candle to the legendary comedy duo of Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis.

Known as Martin and Lewis, they first performed at the Copa in April 1948, and their performance absolutely blew the audience away. They quickly took over as the new headliners, replacing the current one Vivian Blaine, and instead of their originally scheduled two-week stint, the pair ended up staying for more than four months as the Copa's top act. Sinatra's first performance came a few years earlier, in September 1946, and he came back in 1950 to perform regularly at the club. He would continually appear through early 1958, when he stopped headlining the Copa, though it was definitely not from lack of enthusiasm, as Sinatra was one of the club's biggest draws.

The club originally had a maximum capacity of about 1,500, and when it was full, things would be cramped. Besides singers, comedians also frequented the Copacabana's stage. Some of the most memorable names include Don Rickles, Joan Rivers, Mort Sahl, and Sophie Tucker.

It was only for the wealthy and elite

The crowd at the Copacabana was far from your ordinary fare, and included the true social elite of the time. Celebrities were always on hand, often in the crowd as paying customers. The Copa's manager Jules Podell was very popular with many important figures, including tons of sports stars. Pictures show him palling around with Hall of Famer New York Yankee Joe DiMaggio, as well as 1960 Olympic Gold Medal runner Rafer Johnson (via "The Copa"). Other sports celebrities at the club included Clem Lebine of the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers, and DiMaggio's teammates Mickey Mantle and Billy Martin.

Desi Arnaz and his wife Lucille Ball visited the Copacabana, and it was also the site of parties for major motion pictures. One of the most memorable was for the 1941 film "The Lady of Eve," which had the participants dressing up wearing jungle-themed attire. Boxers like Rocky Graziano could also be seen at the Copacabana by those lucky enough to get in, which was far from easy.

Everyone needed either a reservation or a crisp $100 bill to get past the bouncers, and good luck if you were a tourist. As Harriet Wright explains in "I'd Do It Again," the only non-locals to get in were pretty much European royalty or movie stars, and the doormen were well versed in who they should and should not admit. It was exclusivity at its finest, but the Copa more than delivered for entrants.

The New York Yankees' infamous 1957 brawl

On May 15, 1957, several New York Yankees, including greats Mickey Mantle, Billy Martin, and Hank Bauer (all pictured above at Bauer's court hearing), were celebrating Martin's birthday at the Copacabana and watching Sammy Davis Jr. perform. Yet, what started as a celebration turned into a police report. Also there was a group of racist bowlers, and they started causing trouble by saying bigoted comments to Davis Jr. during his performance.

The Yankees, who had a Black teammate at the time, Elston Howard, did not take kindly to the bowlers' comments. Just when Martin was trying to de-escalate things with one of them, another bowler got knocked out cold. Apparently, nobody actually saw who threw the punch, so everyone assumed it was either Bauer, who was an intimidating former Marine, or Martin, who had a history of brawling.

Newspapers immediately put the blame on the Yankees, and Bauer even faced a grand jury, though he was never indicted. It was not until 2020 that Joey Silvestri, a bouncer at the club, came forward and admitted to The New York Times that he in fact threw the punch. Silvestri was off duty when it happened and was only there to see Davis Jr. perform, and he hit the victim two times, breaking their jaw in the process. He claims he did so to stop the bowler from hitting one of the other bouncers, Pauly Pappas, and he never faced punishment.

The music shifted in the 1960s

To make sure that they could keep attracting new patrons while appealing to a younger crowd, the Copacabana had to evolve and adapt over its original 33-year run. In the early years, it meant having crooners and singers like Frank Sinatra and Paul Anka, but by the 1960s, the venue had to start changing things up. Sinatra stopped performing there after 1958, and soon rock and roll and Motown acts started to dominate the club's bookings.

New groups like The Temptations, Gladys Knight and The Pips, and Diana Ross and The Supremes began headlining at the Copa, though stand-up comedians also continued to make waves and were very popular. However, as the 1960s progressed further, even the Copacabana struggled to keep up with the changing times, leading to its downfall. By the time the disco scene was taking shape in the 1970s, the Copacabana was much different than it was three decades earlier. Besides, the exit of the Copa Girls and their replacement by "The Golddiggers" was symbolic of the club's decadent decline.

The club was able to play on nostalgia in its final years before manager Jules Podell's 1973 death, which spelled the ultimate end. Old favorites like Sammy Davis Jr., Joan Rivers, and Knight came back to perform, giving the original Copa its well-deserved send-off.