12 Times Police Botched Crime Scenes In Well-Known Murder Cases

When it comes to homicide investigations, there are few responsibilities more important — especially in the early stages — than the proper securing and processing of the crime scene. The site at which the murder took place (or the victim was discovered, or both) can often yield mountains of useful information. This can range from the circumstantial, such as blood spatter and the placement of the victim's body, to the damning, like fingerprints and DNA evidence, any and all of which could ultimately help to finger the perpetrator of the crime. It's a bit of a numbers game; an investigator can never know which tiny, easily overlooked piece of evidence could constitute the nail in the coffin of the murderer.

Unfortunately, there are more than a few well-known murder cases in recent history in which securing the crime scene was treated not so much like the most potentially important aspect of the investigation, and a lot more like an afterthought. In some of these cases, the culprits were eventually identified; in some, innocent people spent years in prison. There are even instances of sloppy crime scene processing in which the mishandling of evidence had little bearing on the outcome of the case — but there are still others in which it could be argued that, perhaps solely due to the negligence of investigators, those responsible are walking free even today.

Amanda Knox

There are epically bungled murder cases, and then there is the case of Amanda Knox, who — as a 20-year-old American college student living in Italy in 2007 — was arrested for the brutal stabbing death of her roommate, 21-year-old Meredith Kercher. The sensational, tabloid-ready case gained attention the world over, and Knox, who denied all involvement, was convicted and slapped with a 30-year prison sentence in 2009. She only served two years of that sentence; her conviction was overturned by an Italian court in 2011, largely due to the fact that there were about a billion problems with the case brought against her.

The authorities involved with the case, up to and including lead prosecutor Guiliano Mignini (who was later convicted in a corruption case), were zeroed in on Knox from the beginning, despite a dearth of hard evidence against her. Investigators put together their case based on innuendo about her sex life and behavior in the aftermath of the murder, and introduced questionable testimony from unreliable witnesses — and they ignored evidence found at the crime scene which would have exonerated her. Most notably, DNA was lifted from the victim's bra clasp — but not until nearly six months after the crime — that did not belong to Knox, and a bloody fingerprint discovered underneath the victim was largely disregarded because it also did not belong to Knox, and therefore didn't jibe with investigators' certainty that she was responsible. That fingerprint eventually pointed to the real killer: Rudy Guede, an acquaintance of the two roommates who had long maintained that he was indeed present that night, but that somebody else had killed Kercher.

O.J. Simpson

The case of O.J. Simpson, the NFL Hall of Fame running back who was acquitted of the 1994 murder of his ex-wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ronald Goldman, is the single most famous instance of the acquittal of a man who seemed, at every turn before and after his trial, to blaringly broadcast his guilt. From his infamous low-speed freeway chase to the consistent... well, inconsistencies in his story to his disturbing "hypothetical" confession years after the fact, Simpson seems to have done all that he can to ensure that all but his most die-hard supporters will always see him as having gotten away with murder — and if he indeed did, then mishandling of evidence at the crime scene certainly played a part in that.

A piece published by the Tampa Bay Times during the trial cited 16 unidentified "evidence problems" that had been identified by the L.A. Coroner's Office, and in later years, it became known that a goodly number of those problems originated at the scene of the crime. To name a few: a bloody fingerprint found on the house gate went uncollected; photos were taken improperly, and not logged using proper procedure; and pieces of evidence were actually bagged together instead of separately, opening the door to cross-contamination. It has been suggested that the myriad ways in which the evidence was mishandled may just have been enough to let Simpson off the hook — though he would later be found liable in a civil case.

Gary Ridgway

Known for over two decades as the "Green River Killer," Gary Ridgway was a horrifyingly prolific serial murderer; he was convicted of a whopping 49 counts of murder in 2003, and he claimed to have killed over 30 more. Preying mostly on vulnerable women on the fringes of society, Ridgway was able to escape detection for a shamefully long time — particularly since, if the police had done their jobs when his very first known victim was discovered in 1982, all of his subsequent ones may have been spared.

Ridgway was an industrial truck painter, and in examining the clothing of his victim, the Washington State Patrol Crime Lab looked right past a piece of evidence that would have identified his occupation — tiny particles of a unique type of industrial paint that, while microscopic, were still easily detectable in the '80s. The evidence wasn't discovered until years after Ridgway had already been captured, and even the investigators assigned to the case were shocked that such damning evidence could have been overlooked. Said sheriff's commander Frank Adamson, onetime head of a task force assigned to catch Ridgway, "I'm appalled I didn't know that that was even possible ... It would have been nice if we could've saved a life or two — or all of them" (via NBC News).

The Camm murders

In September 2000, tragedy befell the Camm family of Georgetown, Indiana, when three of its members — 35-year-old Kimberly Camm and her children, 7-year-old Brad and 5-year-old Jill — were shot to death inside the garage of their home. Suspicion immediately fell upon family patriarch David Camm, despite the fact that he had a pretty solid alibi: he had been playing basketball at a church function over two miles away at the time. Prosecutors alleged that somehow, he had sneaked away from the court, driven home, murdered his family, and returned without arousing any suspicion — and while this seems improbable, Camm would spend 13 years in prison for the crimes before being exonerated.

His case was not helped by the shoddy treatment of evidence at the crime scene — in particular, a gray sweatshirt found in the corner of the garage that did not belong to any of the Camms. This sweatshirt yielded two separate DNA profiles that would not be checked against the national DNA database for five years — profiles matching Charles Boney, a convicted felon who lived in the area, and his girlfriend at the time, Mala Singh. Due in part to the confusion surrounding this evidence, Camm was twice convicted of his family's murders, with both convictions subsequently overturned, before finally being acquitted in 2013 at a third trial. Boney, whom Camm's prosecutors alleged he conspired with, was convicted of the murders in 2006; in a 2018 interview while in prison, he maintained his innocence, saying that Camm was the true killer.

The murder of JonBenet Ramsey

Unsolved murders don't come much more high-profile than the case of 6-year-old JonBenet Ramsey, the child beauty pageant queen who was found murdered in the basement of her Boulder, Colorado home on the day after Christmas, 1996. The unusual details of the case are numerous and bizarre, from the lengthy, pop-culture quoting ransom note allegedly found by JonBenet's mother Patsy (which claimed that the girl had been kidnapped, and demanded a dollar amount in the exact amount of father John Ramsey's Christmas bonus) to the revolving door of detectives who led the investigation. But perhaps strangest of all was the fact that Boulder police allowed the crime scene to become so thoroughly compromised that one of those lead detectives, Steve Thomas, suggested that it may have destroyed any chance the case ever had of being solved.

Most specifically, the house was not immediately locked down after the discovery of the ransom letter; a family friend, Fleet White, was allowed inside, and detectives even encouraged him to help John Ramsey search the house. When Ramsey discovered his daughter's body, he immediately moved it upstairs; it was then moved again by a detective, and the basement door was left open and unattended. This alone would have tainted any potential evidence to be gleaned from the crime scene, and these errors — among others far too numerous to list here — resulted in the case becoming a big, fat, unsolved black eye on the face of the Boulder Police Department for nearly three decades and counting.

Oscar Pistorious

In 2013, the sports world was stunned when Paralympian Oscar Pistorius — a double-amputee sprinter whose prosthetic legs earned him the nickname "Blade Runner" — was arrested for the murder of his girlfriend, model Reeva Steenkamp, at his home in Pretoria, South Africa. Pistorius contended that he had mistaken Steenkamp for an intruder, and had shot her through the locked door of a bathroom; then, he said, he had donned his prosthetics, beaten down the door with a cricket bat, and tragically discovered his error. Pistorius was convicted of manslaughter in 2014, then re-sentenced in 2016 when a high court determined that he was actually guilty of murder — despite a compelling argument by the defense that a key piece of evidence, the bathroom door, had been mishandled by investigators.

Pistorius' attorney, Barry Roux, echoed media reports at the time that the door had not been stored properly and had indeed simply been sitting around in a station commander's office for some time prior to the trial. A photo taken of the door even appeared to show a boot print from an officer, suggesting that an important piece of evidence had literally been trampled on; this was, however, obviously not enough to spare Pistorius a prison sentence. In November 2023, he was granted parole; he will be confined to Pretoria, and subject to monitoring for five years.

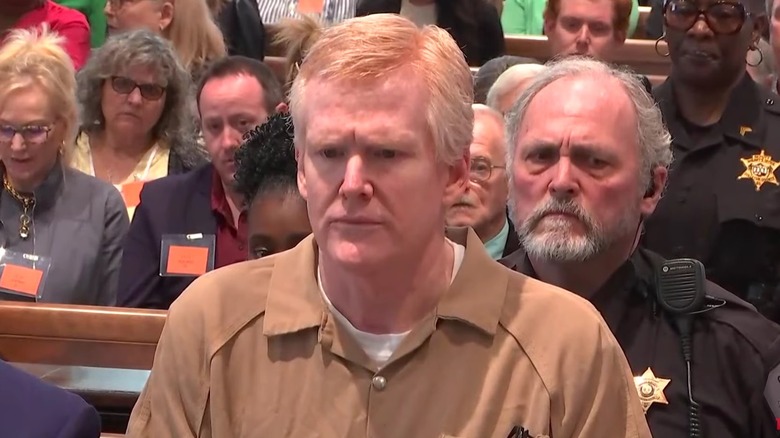

Alex Murdaugh

In early 2023, Netflix viewers were captivated by "Murdaugh Murders: A Southern Scandal," which detailed the 2021 killings of 52-year-old Maggie Murdaugh and her 22-year-old son, Paul, at the family ranch in rural South Carolina. 54-year-old Alex Murdaugh, a prominent area attorney, had quickly fallen under suspicion for the slayings of his wife and son after it became known that he had misappropriated funds from his legal firm in order to support a virulent prescription drug habit; in March 2023, he was convicted and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences. The conviction came despite the fact that, by any measure, virtually all of the crime scene evidence should likely have been thrown out.

Immediately after the murders, a veritable parade of Murdaugh's friends and family members were allowed onto the grounds; first responders disregarded taped-off areas where evidence was to be preserved, and the bodies were left out in the rain for hours. (Shockingly, Murdaugh's brother John Marvin even recalled cleaning up portions of Paul's remains, which were left simply lying around outside, the morning after the murders.) The family housekeeper also testified that the crime scene was not taped off and that she was allowed to tidy up, and even launder items that may have yielded DNA evidence. As of this writing, Murdaugh is fighting for a new trial — although, surprisingly, not on the grounds that the evidence against him was tainted, but due to allegations of improper conduct by a court clerk which may constitute jury tampering.

Tiffany Valiante

The death of 18-year-old Tiffany Valiante was unusual enough to garner national attention; it was featured on the Netflix revival of the classic series "Unsolved Mysteries," and to this day, it has not been explained. What is known is that on the evening of July 12, 2015, Valiante left her house around dusk (without her phone, which was extremely unusual); she had planned to attend a friend's graduation party, which was taking place just across the street. Somehow, by around 11 that night, she ended up nearly four miles from home, along a dark stretch of train tracks — where she was struck by a locomotive traveling at 80 miles per hour.

Investigators nearly immediately ruled Valiante's death a suicide, which was vigorously disputed by her parents, who claimed the teen had absolutely no reason to do such a thing. Based on this initial conclusion, though, investigators failed to take the standard measures involved with processing a crime scene, figuring there had been no crime — which, again, is far from clear-cut. Items found at the scene, including a blood-stained towel and shirt, were basically disregarded by authorities — stored so improperly that, by the time they were tested for DNA (at the insistence of the family), they were of no use. Said Paul D'Amato, the Valiante family's attorney, "There was a gross rush to judgment by investigators ... they never treated the scene like a crime scene and, clearly, mishandled key evidence that we now conclusively learn was useless when finally subjected to DNA testing."

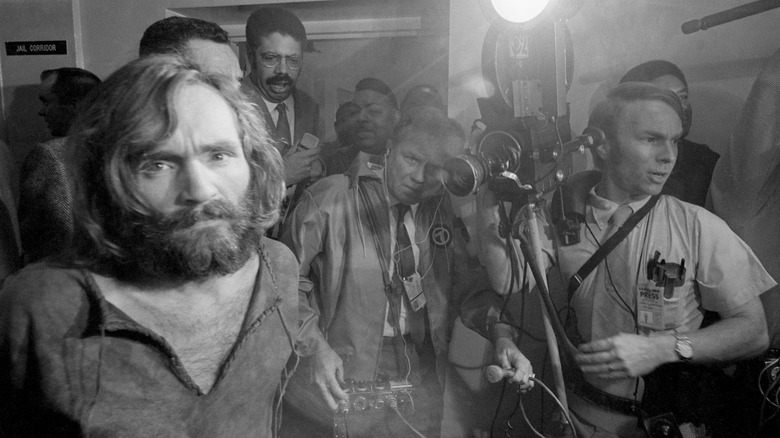

The Manson Family murders

When Sharon Tate, the wife of film director Roman Polanski, and four of her friends were murdered in her Los Angeles home in 1969, it's safe to say that the cops had never seen anything quite like the horrifically grisly crime scene before. Unfortunately, the inexperience showed. Of course, we now know that the crimes were committed by followers of infamous cult leader Charles Manson — but in the 1974 book "Helter Skelter," by Manson's prosecuting attorney Vincent Bugliosi, it was revealed how the cops nearly let Manson and his "family" slip through their grasp due to sheer sloppiness (via Business Insider).

Just for starters, Officer Jerry DeRosa, the first to respond to the scene, promptly obliterated a bloody fingerprint on the button of the home's entry gate by pressing it himself. As more cops arrived, they treated potential evidence like so much detritus, discarding a pair of glasses and the broken handle of a gun grip, and literally tracked the victims' blood in and out of the house throughout the course of the night. The collection of blood samples was also done in a haphazard fashion, and when presented with the glaringly similar murders of grocery store owner Leno LaBianca and his wife Rosemary less than 48 hours later, the police somehow failed to connect the two crimes for months. Manson and his followers were eventually, miraculously, caught — thanks in large part to a group of green detectives investigating the LaBianca murder who took it upon themselves to make the connection for their hard-headed older colleagues.

Kathleen Savio

When former Bolingbrook, Illinois police sergeant Drew Peterson's ex-wife, Kathleen Savio, was discovered dead in her bathtub with a gash to her head in early 2004, it's safe to say that Peterson was given the benefit of the doubt by his fellow sergeant, Patrick Collins. Even though the bathtub was dry, the position of Savio's body was unusual, and her wound was grievous, Collins — who knew Peterson personally — quickly ruled the death accidental. He collected no evidence from the scene, questioned no witnesses, and failed to lock down the house upon his departure. The case was swiftly closed, but Collins' errors in judgment would come to light years later — after the sudden disappearance of Peterson's next wife, Stacy.

Peterson quickly became a suspect in that case, and Savio's body was exhumed and her case reopened — this time, as a murder case. As of this writing, Stacy has not been found, but enough evidence was gathered in the second investigation into Savio's death to charge Peterson with her murder. In 2012, he was found guilty and sentenced to 38 years in prison — a sentence that was more than doubled when, in 2015, he was convicted of attempting to hire a hitman to kill the lead prosecutor in his murder trial.

Colten Boushie

When Colton Boushie, an indigenous Cree man, was shot and killed on the farm of Gerald Stanley in Saskatchewan, Canada in 2016, the case quickly captured the nation's attention. It had all the makings of a media circus due to the racial element; Stanley was white, and the incident was far from being the only one of its type. It's not in dispute that Boushie and his friends had been trespassing on Stanley's property, had attempted to steal on an ATV, and had hit one of Stanley's cars with their vehicle. The point of contention lay in what happened next: Stanley's defense asserted that, while attempting to remove the keys from Boushie's vehicle with the young man in the front seat, his gun accidentally discharged. The prosecution claimed that Stanley shot Boushie in cold blood.

The situation was complicated by the fact that the Royal Canadian Mounted Police failed to properly log evidence at the scene of the crime. The door to Boushie's vehicle, the interior covered in blood, was left open in the rain, compromising blood spatter and gunshot residue evidence; a blood spatter specialist, rather than being brought to the scene, was asked to assess it based on photos, which were improperly lit and of little value. Stanley was ultimately acquitted, and it's tough to argue that the treatment of the crime scene didn't play a huge part in his acquittal. "It's sloppy work," homicide investigator Michael Davis told the CBC. "Obviously, the RCMP needs a lot more training."

Christian Hopson

When 26-year-old Christina Hopson was found dead of a gunshot wound to the head in 2016, there were going to be a lot of questions. Hopson had been dating the son of a Nacogdoches, Texas, sheriff's deputy; she'd had an argument with him just hours before her death. She had been found inside the man's bedroom and had been shot with his father's service revolver, which was in her left hand. Police quickly ruled the death a suicide; Hopson's parents have long maintained that the deputy and his son, who have not been publicly named, were in some way responsible.

Among many questionable factors in the investigation — such as the fact that, despite an extremely high blood alcohol level, Hopson was alleged to have broken into the home, somehow found the gun, and shot herself with it using her non-dominant hand — there is the processing of the crime scene, which was done by a police sergeant who happened to be the ex-wife of Hopson's boyfriend. Nacogdoches police maintain that the sergeant was properly supervised and that despite the bizarre facts of the case, their conclusion that Hopson died by suicide is the correct one. "I know that [Hopson's family] will have a hard time accepting this, probably won't believe it," Nacogdoches County Sheriff Jason Bridges told CBS News, "but there's no evidence to support anything else."