The Most Popular Jobs 1,000 Years Ago

The most common jobs of the medieval world were pretty much what one would expect in a pre-industrial society. Most people lived off the land as farmers of some kind or another and were equipped with a battery of skills to help them survive. The presence of large numbers of artists, smiths, soldiers, and clergy is also no surprise. The Middle Ages were a time of faith, war, and the building of many churches and mosques that needed to be splendidly decorated.

While the Middle Ages is associated the most with knights, peasants, and small villages, there were many cities — especially in Italy — with a thriving legal culture that created one of two potentially surprising inclusions on this list — the notary. While one might be tempted to think that modern bureaucracy is a product of the last 200-300 years, much of modern legal culture originated in medieval Italy, where a university course of study was designed to train them. Finally, there is sex work, a common occupation that flies in the face of medieval stereotypes of a sex-repressed Catholic society. Here are some of the Early Middle Ages' most popular professions and why they thrived.

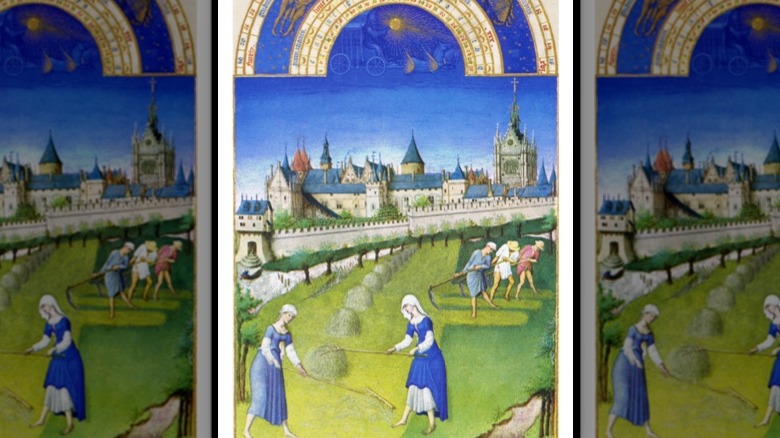

Farmer

In the 11th century, especially in medieval Europe, the vast majority of people – nearly 90% of the population, depending on the place – were subsistence farmers. Being a subsistence farmer was not a matter of just digging a hole – it required practical skills and knowledge about weather, animals, tools, and building basic structures like one's house.

According to Professor Lynn Nelson of the University of Kansas, these were often compact villages made up of a handful of homes. Some owned their land, while others worked in various arrangements with feudal lords, known as manorialism. In a manorial arrangement, peasants worked land owned by a local feudal lord. They could be free rent-paying tenants or serfs. Serfs were not quite enslaved, but bore a handful of similarities to those that were. They were bound to the lord whose land they were born on and worked. They had to give a portion of their harvests as rent, lacked freedom of movement, and freedom to marry. However, the lord did have the theoretical obligation to protect them and treat them justly.

While it is impossible to generalize about the lives of medieval peasants living in an area that stretched from Spain to Russia, it seems that overall, life was not as bad as is depicted in movies. Generally, as long as there was peace and good weather, there was enough food available, especially as agricultural advances allowed greater yields. Even the poor could enjoy meat from time to time – as long as the weather cooperated and peace reigned.

Mercenary/adventurer

Eleventh-century rulers needed soldiers for their constant wars. For dispossessed nobles, these wars were golden opportunities to forge their own kingdoms amid the chaos of conflict, or make their names before returning to seize what was theirs. King Harald Hardrada of Norway, for instance, served in the Byzantine Varangian Guard across the Mediterranean, before returning to Norway in triumph to serve as king.

If there is one man who best epitomized the 11th-century mercenary, it is Robert "le Guiscard" d'Hauteville. Robert was one of 12 sons of a minor Norman noble named Tancred. Since his father's estate was too small to provide sufficient inheritance, Robert left home and joined his siblings in Southern Italy, where his brother Drogo had already carved out a small fiefdom.

Drogo sent Robert to Calabria, the toe of Italy, with virtually nothing but a small band of men. Through raids, wars, and shrewd diplomacy, this impoverished yet cunning and ambitious mercenary knight became a local potentate, cementing his position with a marriage to Sichelgaita, the Duke of Salerno's sister. With papal blessing, Robert evicted the Byzantines from Southern Italy by 1071, and conquered the fractured Muslim Sicily by 1081. Despite his previous reputation for brutality, Robert opted, likely in the name of practicality and stability, to allow his non-Catholic subjects to continue practicing their religions and customs as before. By his death in 1085, he was master of Southern Italy and Sicily, and had even begun probing Byzantine Greece for further conquests in the Balkans.

Clergy

The Middle Ages were an age of intense faith, in which the Catholic Church exercised both temporal and spiritual authority across Europe. Naturally, the clergy formed its own special estate (social class) in medieval society, making up around 10% of the population, depending on location.

Eleventh-century Catholic priests functioned similarly to those today. They said Mass, heard confessions, oversaw marriages, funerals, communion, and more. However, the structure of the medieval Catholic Church they served was a little less centralized. Often, churches were privately owned, meaning the priests were not paid by the Vatican, but subsisted off donations and offerings from their flock. Because almost every village and all bigger towns had at least one church, there was naturally a need for a lot of priests.

In the Middle Ages, clerical shortages were not a problem, though, because incentives to join the priesthood abounded. It was a way to get an education – if even a rudimentary one, according to Edward Cutts' "Parish Priests and their People." In medieval England, it was open to all social classes, although pilates such as bishops were usually drawn from the nobility. Finally, there was no celibacy in the 11th century. The First Lateran Council that decreed clerical celibacy occurred in 1122. Thus, an 11th-century priest could technically be married. Those who did not kept concubines – a practice that continued even after celibacy became a requirement. In one remarkable case, per the Christian History Institute, a priest had three children, who also all became priests.

Steppe nomad

On the Eurasian steppes lived various mostly Turkic-speaking nomadic groups, like the Khazars, Kyrgyz, Oghuz, and Pechenegs. Unsurprisingly, their lifestyles were very different from those of Europe and the Middle East's sedentary inhabitants. According to an article published in the Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, these nomads eschewed agriculture in favor of mobile pastoralism centered around camels, sheep, yak, and cows.

Chroniclers like the Baghdadian Al-Jahiz had little good to say of these nomads, describing them as little more than uncivilized robbers. But although relations between nomads and sedentary communities could be hostile, they were not always so. Nomads depended on trade with towns and cities of the steppe (and vice versa), leading to a symbiosis upon which the steppe economy depended. In fact, it was not uncommon for pastoralists to alternate between nomadic and sedentary lifestyles, depending on the times.

Although Al-Jahiz was no fan of nomads, the Islamic Abbasid Caliphate in which he lived employed them frequently as mercenaries – and they eventually took over. According to historian Rashid Ismailov, they were favored not just as soldiers, but also as administrators. In Egypt, for instance, they provided around 30% of the governors, who often ruled de facto, independently of the caliphate in Baghdad. Then there were those Turks who forged their own fully independent states. The most important were the Seljuks, whose empire spanned from Iran to Anatolia. Their primary achievement was making modern Turkey Turkish, with their victory against the Byzantines at Manzikert in 1071.

Armorer/blacksmith

Wars and battles were a common fact of life in the Middle Ages – whether in the 11th century or later. To provide kings and nobles with their weapons and armor to fight their wars, smiths and armorers were needed, making this a popular and prestigious occupation at the time.

Armorers were highly regarded not just due to the necessity of their craft, but the amount of work that went into producing pieces – whether chain mail or plate. During the Early and High Middle Ages (including the 11th century), the most popular form of armor was chain mail armor, which was made of interlinking iron rings and required a great deal of time, skill, and manual dexterity to produce. It is most famously linked to the knights of Normandy, who can be seen donning chain mail on the Bayeux Tapestry depicting the Battle of Hastings.

Unfortunately, relatively little is known about early medieval armorers – detailed records do not appear until the Renaissance. However, armorers' guilds – associations of armorers and smiths who banded together in common interests (basically the forerunners of modern unions) — already existed by the 11th-12th centuries or so around Europe, suggesting that organized armor production was established early on as a local affair. But as technology improved, certain cities overtook the rest and became centers of smithing, principally in Northern Italy and Southern Germany/Austria. By the Renaissance, their products were considered the best money could buy.

Merchant/explorer

Although the 11th century (and the early Middle Ages in general) is seen as a sort of "Dark Age," it was anything but. Population increases led to migrations, which resulted in the (re-)establishment of commercial contacts between far-flung regions of Eurasia and Africa. It was a "global millennium," according to historian Valerie Hansen (via History Extra).

With the uptick in commercial activity came an increase in merchants and explorers – some of whom, like the Vikings that landed in Canada under Leif Erickson, were also warriors. These men dealt in everything. In the 11th century, that could mean chinaware from the Far East, salt and gold from West Africa, textiles from Northern Europe, and most of all, enslaved people. Indeed, the enslavement trade flourished in the 11th century, with more than 10 million people being sold in markets throughout Europe and the Middle East. The primary victims were Eastern European Slavs, whom Islamic rulers in particular sought out as bodyguards and concubines.

Being a merchant was not without risks, of course. There were bandits, pirates, and all sorts of other dangers out on the roads and seas. But it was equally rewarding, and often opened kingdoms to new diplomatic and religious influences. Through mercantile and eventual diplomatic contacts, pagan rulers such as Kievan Rus' St. Volodymyr became Christian in 988, while the Turkic Khazars embraced Judaism, most likely through contacts with Jewish merchants.

Carpenter

Wood was everything in the Middle Ages. It was used for building ships, homes, frames for stone structures like churches, furniture, paper, and more. For the more complex projects in particular, skilled carpenters were needed to make sure that things were done correctly. Carpenters were common during the Middle Ages, although their exact numbers in the 11th century are unclear due to sparse records.

Although the exact percentage of carpenters in the 11th century is unclear, the predominant use of wood in military and civilian architecture suggests they were common. After the 1066 Norman conquest of England, the invaders consolidated their authority by building castles. But stone castles were expensive and time-consuming, so the Normans opted for wooden fortifications called motte-and-bailey castles, which required carpenters to build. As medieval cities grew, they needed carpenters to build new structures and maintain existing ones. Thus, the craftsmen also grew in number and organized into guilds as cities hired them out. By the 15th century, they were the second-most-common occupation in the French city of Montpellier, per historian Lucie Laumonier (via Medievalists), a likely reflection of wider medieval Europe.

In Eastern Europe, where stone was lacking, carpentry was the main material for building even the most beautiful public works. The Moscow Kremlin, for instance, was originally made of wood. The city of Novgorod boasted beautiful landmarks like the 11th-century wooden Cathedral of St. Sofia, which, according to the Russian Primary Chronicle, boasted 13 cupolas, proving that one did not need stone to make beautiful churches.

Artist

Around 1000 AD, Europe experienced an artistic revival dubbed "Ottonian," after the famous Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great. The style, which combined Italo-Byzantine and German traditions to various degrees, resulted in a large output of illuminated manuscripts, sculptures, paintings, jewelry, and churches. Meanwhile, the expanding power of the Catholic Church was birthing hundreds of Romanesque-style cathedrals during the 11th and 12 centuries, such as the cathedrals of Pisa in Italy, Mont-Saint Michel in Brittany, and Augsburg in Germany.

To produce and decorate these masterpieces of art and architecture, skilled artists were needed. Before the Ottonian period, most artists were monks, who produced illuminated manuscripts as part of their vocation. In the 11th century, however, artists were becoming their own profession — men paid specifically to produce paintings and sculptures to decorate churches and private homes. One can presume that, as in the Renaissance, the very best were paid handsomely for their efforts.

Medieval artists were often itinerants, going where the work was and allowing artistic styles and influences to cross borders. Some studied abroad, like Ottonian ivory carvers, who appear to have picked up their skills in Northern Italy. Nor was religion a barrier. Fatimid mosaicists from Islamic Egypt, for instance, were known as some of the best in the Mediterranean, helping build palaces and the Al-Azhar Mosque in Cairo. But when the Catholic Normans conquered Sicily, their religious/cultural loyalties were no barrier to taking jobs under their new rulers, designing the splendid ceiling of the Palatine Chapel in Palermo.

Sex worker

Although medieval Europe is thought of as a sex-repressed society due to the influence of the Catholic Church, medieval folk believed that too little or no sex at all was the cause of health problems, especially in men. The Catholic Church, meanwhile, viewed the "world's oldest profession" as a lesser evil. Even the famed St. Augustine believed sex work kept society stable by giving men access to legal sex away from polite society, stopping them from wrecking society through adultery with "respectable" women, sinful behavior, and rape.

To fill the need for sex, working women were required. These were often recruited from the urban and rural poor – women who had few other options. City authorities regulated the trade, restricting brothels to the most run-down and peripheral areas of town, and requiring sex workers to identify themselves through clothing. Brothels often were licensed and taxed on their earnings, although city authorities sometimes cut out the middlemen by opening municipal brothels. Interestingly, laws prohibiting beatings and restricting the number of clients a woman could see in a day were also on the books – somewhat forward-thinking by medieval standards.

Although sex work was supposed to be an outlet for lustful men and poor women with no other outlet, things hardly ever panned out as planned. According to historian Andrew McCall's "The Medieval Underground," even wealthy, high-status women frequented brothels as sex workers to satiate forbidden sexual desires. But there was a price – frequent outbreaks of sexually transmitted diseases.

Butcher

Regularly eating meat was generally a luxury in the Middle Ages, but it was accessible in good times to commoners – albeit at lower quality. The best cuts, then as today, were provided by butchers, who formed a special class and guild in medieval cities and kingdoms.

The importance and popularity of the butchers varied across the medieval world, but it seems they formed around 3-4% of the population of an average medieval city in the 15th century. While one cannot extrapolate those numbers for earlier periods, the presence of the guilds as early as the 12th century suggests that it was a popular profession. In Italy, particularly in the Italian city of Parma, butchers were celebrities.

Although little is known about 11th-century butchers, by the 12th, they had organized a guild in Parma, according to La Passeggiata Dei Sapori. But the guild's influence extended well beyond the dirty work of killing and butchering animals for consumption. It was a member of L'Arte dei Beccaj, a political grouping of four guilds, who together worked to tilt Parma's government toward their economic interests. Contrary to the popular image of the filthy Middle Ages, butchers were generally subject to hygiene laws, including a ban on selling tainted meat. So influential were the butchers, that when Parma celebrated the Feast of the Assumption in August, the butchers would be the second – after the local mayor – to process into the cathedral – a huge honor for what today would be considered a blue-collar trade.

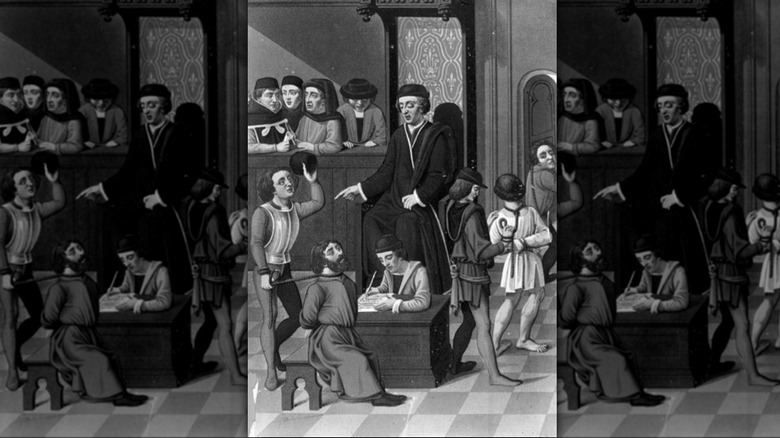

Notary

Eleventh-century Europe, for all intents and purposes, created the modern notary. Notaries in 11th-century Europe were more scribes and administrators than notaries. They did not have any specific training in Roman law as their counterparts down south did. Literacy was usually the main requirement, since it often entailed writing up and keeping records, writing legal documents and letters, and promulgating them. But in Italy, things were changing quickly.

According to "Medieval Notaries and Their Acts," the Mediterranean world – especially Italy – revived the old Roman concept of the notary, which entailed officializing (i.e., notarizing) legal documents issued from the ruling authority, as well as commercial contracts and other legal documents between individuals. Because such work was more complicated than simply copying down the words of a ruler, Italian states put much stock into properly training their notaries.

There were several requirements for aspiring notaries. One had to be literate, know Roman law, and get an appointment by the appropriate authority – whether a city government or ruler. Otherwise, he could find employment with a private individual. But learning Roman law required going to law school. So in the 11th century, the University of Bologna established a faculty, complete with law professors – a great example of early university credentialing, known today as a degree. The Holy Roman Empire followed this tradition, requiring notaries in imperial administration to pass a civil service exam. By the 13th and 14th centuries, Italy counted on hundreds of notaries just in its small city-states.