Tragic Details About The Deadly Knickerbocker Theatre Roof Collapse

In January 1922, Washington, D.C., was buried under the worst snowfall the capital has ever seen, even to this day. More than 2 feet blanketed the city from January 26 to 29. Despite the epic storm, about 300 people trudged through the snow to watch an evening of films at the Knickerbocker Theatre.

The Knickerbocker had opened in 1917 and, in a sign of the major changes happening in the world of entertainment, was only ever a movie theater. It was one of the nicest of its kind and could seat over 1,000 people. It had an iconic triangle design ... and a flat roof. The latter meant that the snow had been building up in large drifts on top of the theater when disaster struck on January 28. Unable to support the weight of the snow, the roof collapsed on those in attendance. Of the 300 or so people in the theater that night, 98 would not leave alive and almost none would come out unscathed.

Survivors said there was no warning

It was almost exactly 9 p.m. and the audience in the Knickerbocker Theatre was enjoying their evening out. Everything had been normal until that point, with the first film, a silent comedy called "Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford," just finishing, and the live orchestra playing the lullaby "Sweet and Low."

While more recent accounts of the event claim that during the film there were some odd hissing and ripping noises and plaster dust fell from the ceiling, in the immediate aftermath, survivors told reporters there was no warning at all for the patrons until a shout went up as the center of the roof caved in. That was followed by a deafeningly loud noise — compared to thunder or an earthquake — when the whole thing collapsed, along with a large portion of the back wall. The Washington Herald summed up the reports of survivors on what happened next: "a moment of unearthly silence and then the moaning and shrieking of suffering humanity."

While the whole roof came down, the collapse was not equally terrible everywhere, with the area at the front of the theater slightly protected by some columns. In the back, the force of the roof brought the balcony down with it, and the whole thing ended up only about 18 inches from the floor. The theater was now a mix of the living and dead, some hovering between the two states, and all were trapped under concrete, twisted metal, and feet of snow.

It took hours to begin an organized rescue effort

When the roof collapsed, witnesses outside the theater immediately did what they could to help. Locals donated blankets for the injured. A boy who was small enough to get through some of the wreckage crawled inside to bring a family that was trapped a drink of water.

However, despite the help of these individuals, there was no organized rescue effort for several hours. Even when professionals did arrive on the scene, there were complications, with the AP reporting (via The Arizona Daily Star) that the large amount of gear brought by virtually every fireman in the city only added to the confusion. Cars that had been abandoned in the snowy streets blocked the ambulances trying to get to the wounded. Friends and family of those in the theater started to arrive as news of the disaster spread, and the first responders had to use time and manpower to hold these people back when they tried to run onto the debris to search for their loved ones themselves.

It took the arrival of the Marines to bring some semblance of order. Even then, it was discovered that the twisted metal and concrete were impossible to move by hand, and the rescue was delayed further while as many blowtorches and hacksaws as possible were rounded up. By 2:30 a.m., a full five and a half hours after the roof first collapsed, the rescuers were still trying to break through the wreckage of the balcony to reach those trapped underneath.

Those who were buried faced an agonizing wait

While hundreds of people outside worked on rescue efforts, those who were trapped waited and waited ... and waited. A few days after the disaster, The Washington Herald spoke to Joseph Younger, an architect who had been at the theater with his wife. While they both survived (although they were hospitalized with injuries), Younger said the wait was its own kind of torture: "It was five hours before my wife was rescued, and six before they got me out. It was like an eternity. It was maddening."

Others did not survive that wait. Younger said, "... we could tell fairly accurately that the woman nearby was dead. She had screamed, then moaned, then grown still." She was far from the only injured or dying individual crying out in pain. According to a report in The New York Times, the moans of agony from those waiting long hours for rescue could be heard by onlookers standing in the street.

Lest these vivid descriptions not give a good enough understanding of just how horrific the disaster was, Younger made a very pointed comparison that everyone in January 1922 would have understood all too well. Only a few years before, he had been fighting in Europe during World War I, and he had no difficulty deciding which deadly situation was more terrifying: "... it was far worse than the Argonne forest. I was wounded there and I saw some pretty terrible trench scenes, but nothing like this."

It took a long time for the full scale of the tragedy to become clear

While those inside the theater were in a nightmare that involved being trapped, suffering, and dying, those on the outside were trying to figure out how bad the situation was.

For many hours after the roof collapsed, no one had reliable information about how many people had been in the Knickerbocker that night. The AP's estimates in the Arizona Daily Star were anywhere from 150 to 500 audience members watching the film, while The New York Times said the number could be as high as 1,000. So while rescuers were trying to get to those trapped, they didn't even have an accurate count of how many people they were looking for.

Not having any idea how many were inside meant that the earliest newspaper reports ran fatality numbers that were a fraction of the final, shocking total. One Associated Press report dated January 28 that was printed in the Richmond Times-Dispatch said there were at least 15 dead, while the AP report from the same day in the Arizona Daily Star increased the number slightly to 17. Even by the next day, the casualty numbers in the same paper were only up to 20. The New York Times spoke to first responders who said they thought the total dead would end up being 60 to 75, but for whatever reason the paper gave another unsourced estimate as well — eventually proven to be the most accurate — of up to 100 dead.

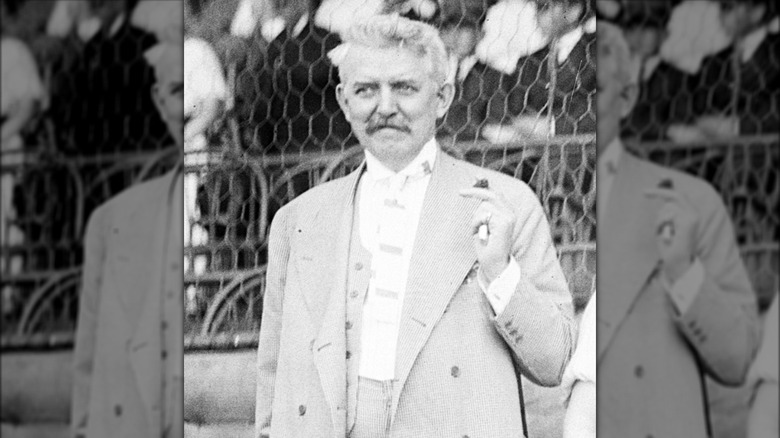

Victims included everyone from a former congressman to young children

The official Knickerbocker Memorial website lists the known ages of the 98 victims, which ranged from 7 to 71. Victims included members of the government, musicians in the theater's orchestra, businessmen, school children, journalists, members of the military, and many more. The sister of the Guatemalan ambassador was one of the dead, as was the former congressman Dr. Andrew Jackson Barchfeld (pictured). Five of the victims were students at nearby Georgetown University. A member of the orchestra who didn't make it had gotten married four days before. One woman who survived said her husband shoved her out of the way as the roof came down; he did not make it. A 9-year-old boy who survived the initial crash held the hand of a rescuer as he waited hours to be rescued, eventually dying of his injuries.

Families were decimated by the disaster. One 4-year-old girl lost both of her parents and was sent to live with relatives. A father and his adult son and daughter were all killed. One report said a 9-year-old boy had to identify the bodies of his mother, father, and two sisters.

Identifying many of the victims was a tragedy in and of itself. The weight of the roof and balcony falling on them meant that many bodies were crushed to the point of being unrecognizable. In many cases, it wasn't their bodies that were identified at all but items of clothing or jewelry they were known to be wearing.

The snow alone probably wouldn't have been enough to cause the disaster

Even with a record snowfall blanketing the city, you would probably not think it would get to roof-collapsing levels that easily. Officially, 28 inches of snow was dropped on the city by the snowstorm, but some witnesses said that far more than that had accumulated on top of the theater itself. The Washington Times got a quote from E.L. Scharf, who said the danger was clear: "... about three hours before the roof collapsed ... I called another man's attention to the fact that a large conical mound of snow had been formed on the roof by the swirling of the wind. ... This conical mound I saw must have put a strain of at least 100 pounds per square foot on the roof."

However, the city's Engineer Commissioner Charles Keller told the same paper that he believed that even if it was true there were many feet of snow on the roof, it would still weigh less than half of what the structure was built to hold. Meanwhile, District Inspector of Buildings John P. Healy did admit that even 26 inches of snow could mean a load of 30 lbs. per square foot — 5 lbs. more than any of the city's theaters were required to withstand.

In the end, these numbers and estimations were meaningless because they were all based on the theater being built with safety in mind. In reality, the snow was only part of the problem.

An inquiry found major issues with the theater's construction

Immediately after the disaster, all theaters in Washington, D.C., were ordered closed and buildings underwent inspections. Multiple inquiries were called for, and several were eventually put together to try to find out what the heck had caused the roof of the Knickerbocker Theatre to collapse so suddenly. The belief was that the snow alone could not possibly have been the reason. There had to be something else about the building that resulted in it being unable to take the weight.

From the beginning, it seemed that sloppy construction practices must be to blame. One engineer who viewed the wreckage believed it would come down to the use of shoddy materials. Despite this, the owner of the theater, Harry Crandall, said he was fine with the probes and hoped that those found responsible for the disaster faced justice, according to a February 1922 issue of the Evening Star.

In the end, it was discovered that the steel beams that supported the roof were barely attached to the walls of the theater, instead basically just resting on top of them. This meant the snow had a much greater effect than if the beams had been anchored correctly. A grand jury later recommended five people be charged with manslaughter, including the architect, Reginald Geare. However, according to building codes at the time the theater was constructed, there was nothing illegal about the shortcuts the builders had taken, so no one ever went on trial for the Knickerbocker disaster.

The victims and their families never received compensation

Despite the inquiry finding that there was plenty of blame to be passed around, the courts decided otherwise. Victims and their loved ones filed lawsuits for a whopping seven decades following the Knickerbocker Theatre disaster, and all of them ended up being dismissed because judges were unsure who was really liable at the end of the day. When the Supreme Court had an opportunity to hear one of the main cases, they turned it down, letting the lower court ruling against the victims and their families stand. In the end, no one affected by the tragedy was ever compensated for what happened.

This meant it was up to the survivors' loved ones to help them. One poignant story involved Oreste Natiello, a member of the theater's orchestra who was playing his violin at the time of the collapse. His injuries included losing an arm, which meant playing his instrument — and making a living — was no longer possible. Two years after the disaster, he was living in Kentucky, and a local vaudeville troupe decided to raise money for him, putting on the Natiello Benefit Performance. An audience of over 2,000 people watched actors, musicians, and dancers, who all pitched in to help another entertainer who was suffering. With the money the event raised, Natiello was able to start a new chapter in his life, choosing to stay in Kentucky and becoming a doorman.

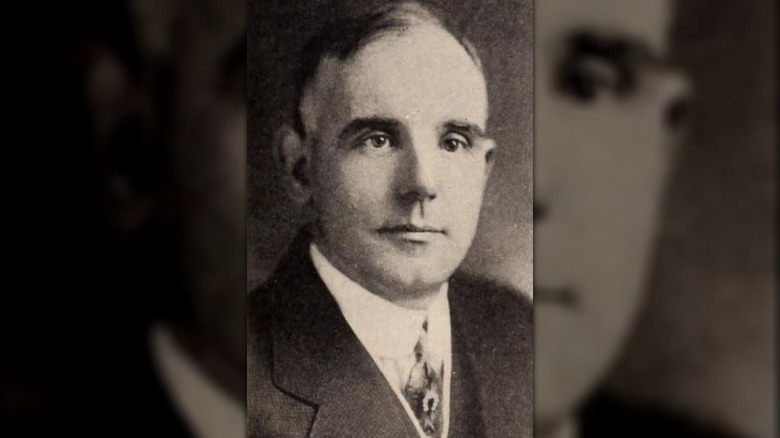

The Knickerbocker's architect and owner both later died by suicide

The results of the inquest were disastrous for the owner and architect of the Knickerbocker Theatre. Architect Reginald Geare was charged with his role in the tragedy, although it never went to trial, and his career ended in disgrace. Multi-millionaire Harry Crandall (pictured), who owned several other theaters as well as the Knickerbocker and was very active in the budding film industry, ended up having his own career ruined as well. Both men were said to be haunted by what had happened that January night in 1922.

In August 1927, Geare was found dead in his home, aged just 37. He had died by suicide. The brief report of his death in The New York Times not only gave him the wrong middle name (Wakefield instead of Wyckliffe) but only mentioned his connection to the disaster at the Knickerbocker, complete with death toll, and details of how he had taken his own life. It was a sad end for a young man who had once had a very successful career, including designing some D.C. area homes now worth millions of dollars.

A decade after Geare's death, Crandall also died by suicide. While the architect's death was perhaps more tenuously connected to the mental and emotional effects of the tragedy, Crandall was reported to have written a note that left no question he had never gotten over what happened.

It is tied for the third deadliest structural failure in U.S. history

The death toll of the Knickerbocker Theatre disaster continued to climb, with many victims dying of their injuries after being rescued. The official toll ended up at 98 people dead and 133 injured. Many of those who were lucky enough to survive still suffered life-changing injuries, losing legs and arms in the disaster. According to reports at the time, in at least one case, a man needed to have his arm amputated at the elbow in order for rescuers to free him from the rubble.

When the Knickerbocker roof caved in, it became the second-deadliest non-intentional structural collapse in United States history, with its death toll topped only by the Pemberton Mill disaster in 1860. In that tragedy, it's believed as many as 145 textile workers died when a wall of the mill disintegrated, bringing the multi-story building and the many pieces of heavy industrial machinery down on the workers inside. The Knickerbocker held its ignominious second-place spot until 1981, when a walkway collapsed at a Hyatt Regency in Kansas City, killing 114 people and injuring more than 200.

Almost exactly 100 years after the January 1922 disaster in Washington, D.C., a sudden and unexpected building collapse 1,000 miles south would tie it exactly for the number dead. On June 24, 2021, a section of a 12-story tall condo tower in Surfside, Florida, failed for reasons that are still unclear as of 2024. There too, 98 people lost their lives.

If you or someone you know is struggling or in crisis, help is available. Call or text 988 or chat 988lifeline.org