The Major Detail Thomas Jefferson's Gravestone Leaves Out

Thomas Jefferson wanted the world to think him a humble, dutiful man without ambition. It was an image of himself that he may have sincerely believed. But John Adams, who was Jefferson's good friend and bitter rival in turns, once wrote to his son that Jefferson was "ambitious as Oliver Cromwell" (via David McCullough's "John Adams"). And when Jefferson did make an attempt at retirement, after resigning from George Washington's cabinet, he confessed to friends and his daughter that being removed from the world, and from politics, was ruinous to his mental health.

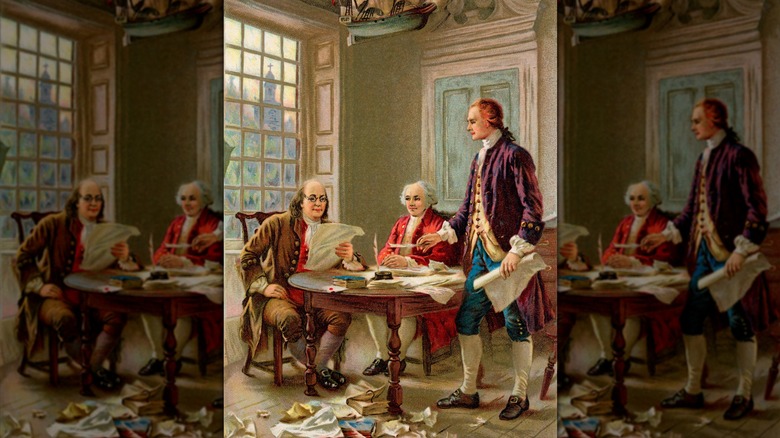

Whether duty, ambition, or peace of mind was his chief animating force, Jefferson certainly didn't pass over opportunities that added glory to his name. Nor was he indifferent to how his legacy would be interpreted after he was gone. As perceptions of the Declaration of Independence took on an awed fervor, Jefferson became sensitive about claiming authorship and refuting any suggestion to the contrary. When he handed down the writing box he used for the Declaration to a relative, he noted that it might one day be treated with the same reverence shown to the relics of saints (per Gordon S. Wood's "Friends Divided: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson").

Jefferson's curation of his legacy extended even to his death. He wrote the epitaph for his own gravestone, which he designed in the shape of an obelisk. He listed the three achievements he wished to be remembered for: authoring the Declaration, founding the University of Virginia, and writing the statute of religious freedom for Virginia. Left unmentioned was the fact that he had been president of the United States.

Jefferson claimed to be a reluctant president

Thomas Jefferson never mentioned why he didn't include his presidency among the achievements he wanted engraved on his tombstone, and with centuries of distance, the omission may seem uniquely strange to us. Historians have long considered him among the greatest of U.S. presidents; a C-SPAN survey has seen him place 7th for over two decades. And Jefferson's was a transformational administration and was seen as such in his own time.

But before achieving the highest office in the land, Jefferson maintained that he didn't want it. His heart, he maintained, was at Monticello. John Adams suspected that such claims were a political act, an effort to position himself well in the public mind should the opportunity arise to win power. But when it became clear that Adams had bested him in the 1796 election (fought, as was custom, through newspaper surrogates rather than the candidates themselves), Jefferson wrote to express his congratulations and to insist that he always hoped and expected that Adams, his senior partner in so many endeavors, should come before him as president. And some modern commentators, among them those behind The Thomas Jefferson Hour, have judged his reluctance as sincere.

Be it a job he took on unwillingly or a position he coveted, Jefferson wasn't sorry to leave it after two terms. Before he ever set foot in the White House, observation of his predecessors had convinced him that the presidency was "a splendid misery" (via Monticello). Jefferson found his popularity waning in his second term, the result of a disastrous embargo intended to steer America away from the Napoleonic wars.

Jefferson valued his other services over the presidency

The presidency may not have been Thomas Jefferson's most cherished role in public life, but it still represented the height of his political power and encompassed a number of his great achievements. So the question remains: why wouldn't he have mentioned it in his epitaph? Why, for that matter, did he leave out his time in the Continental Congress, his diplomatic work in France, and his governorship of the state of Virginia?

Asked about Jefferson's tombstone, historian John Ragosta volunteered (via Vimeo) that none of these offices were as important to Jefferson as what the American Revolution represented to the world. "Jefferson really viewed his contribution, and his generation's contribution, was creating the United States and getting it up and running," said Ragosta. At the heart of the American experiment were the fundamental principles of political freedom, religious freedom, and an educated populace. The Declaration of Independence, the statute on religious freedom, and the University of Virginia represented those three principles. They also represented contributions Jefferson made to American life that would have an ongoing impact.

The obelisk Jefferson envisaged wasn't erected until seven years after his death, and it almost immediately faced vandalism in the form of overeager tourists chipping pieces off to take home. It was relocated several times before finding a home at the University of Missouri, by the choice of Jefferson's descendants. The monument currently at Monticello was commissioned by Congress, while the original is on display at the university's Jesse Hall. It names Jefferson's three achievements as he described them and, true to his wishes, has "not a word more" (via Monticello).