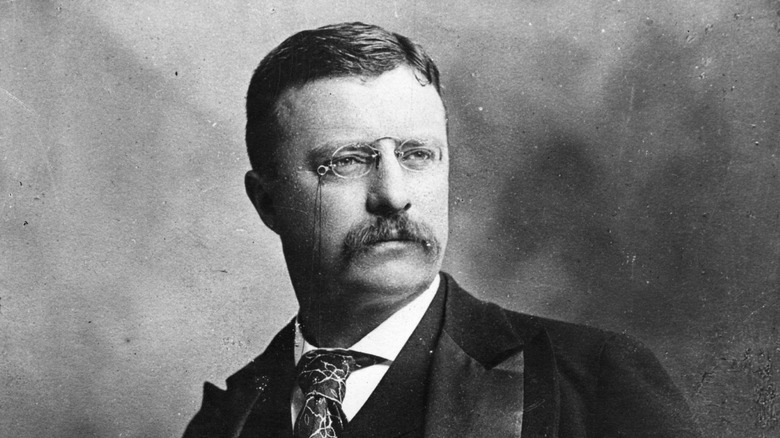

The Grim Details About Theodore Roosevelt's Death

Theodore Roosevelt was lionized during his lifetime as a president who exuded strength and stood as an embodiment of the United States' growing power. One legendary incident that occurred during his public life involved an assassination attempt against him as he was due to give a campaign speech at an auditorium in Milwaukee on October 14, 1912. Though a gunman wounded the politician, rather than go straight to the hospital, Roosevelt stayed — telling the crowd, "It takes more than that to kill a bull moose" — and proceeded to deliver his entire 90-minute speech before seeking treatment.

Despite Roosevelt claiming that the wound was superficial, doctors were unwilling to remove the bullet from his chest on safety grounds. The injury contributed to his poor health in his declining years, though when he died at the age of 60 it was of an unexpected illness that took his doctors entirely by surprise. Here's what we know.

Theodore Roosevelt's declining health

The assassination attempt against Theodore Roosevelt — who was running as a third candidate as leader of his independently formed Bull Moose Party — made headline news, becoming arguably the biggest story of the presidential elections. The incident and his reaction gave him a great deal of valuable exposure. However, Roosevelt remained an outsider, and though he took a respectable 27% of the overall vote having split Republican voters, it was not enough to get him into office.

Instead, his injury, sustained at the age of 53, contributed to worsening health in his later years, particularly rheumatoid arthritis. He also suffered from asthma, which plagued him especially as a child, when treatment for the condition was minimal. In 1918, Roosevelt was hospitalized. His health had reportedly nosedived following the harrowing death of his youngest son, Quentin, an aviator who was shot down in battle during World War I. Roosevelt felt immense guilt at his son's death, having supported the war effort and encouraged young men to sign up. Indeed, he wished that he had been young enough to go in his son's place, according to a letter he wrote after Quentin's death (via "When Trumpets Call" by Patricia O'Toole).

A sudden death

Despite these factors, Theodore Roosevelt was still considered a healthy and vigorous man as he entered his sixth decade, and he showed no sign of slowing down. In the year prior to his death, he was reportedly the favorite to win the Republican candidacy for the 1920 Presidential Election, and he remained a visible presence in public life, contributing to magazines and making public appearances. According to The New York Times, toward the end of his life he was asked about his health, to which he replied with a single word: "Bully!"

However, by the start of January 1919, he had undergone two months of treatment for what was described as "inflammatory rheumatism," with doctors visiting him twice a day. One physician recalled that on January 5, the night before Roosevelt's sudden death, he had been to visit the ex-president, who seemed to be in good health and full of curiosity about the world rather than his own condition. However, by 11:00 p.m. that night, Roosevelt began to complain of breathing issues and a sense that his heart wasn't beating correctly.

After a visit from the doctor, his condition seemed to improve, and he went to sleep. In the early hours of the morning, a servant went to check on Roosevelt and found that his breathing was shallow. He died in his sleep of what doctors later confirmed was an embolism that had traveled to his lungs.

Shock and mourning

The news of Theodore Roosevelt's death was a terrible shock to his family and friends and the nation he had dedicated his life to serving. The home where he spent his last night was in Oyster Bay, Long Island, where Roosevelt was considered a pillar of the community. After the news of his death broke, flags in the town flew at half-mast.

Roosevelt's death was shared among his close friends and family by telegram. Per Presidential History, his son, Archibald, sent a message to his brothers in Europe, stating: "The old lion is dead." Meanwhile, Roosevelt was given a bold farewell in American newspapers, the obituaries of which heralded his achievements as the leader of the Rough Riders cavalry troop during the Spanish-American War and, later, as the nation's president. He had also made his name in later life as an explorer, which rounded off the image of Roosevelt as the definitive man of action.

For many, Roosevelt's sudden and unexpected death in his sleep was an ill-fitting end for so dynamic and energetic a figure. However, his friend Thomas Marshall, who was vice president at the time of Roosevelt's death, suggested (per New York State Library): "Death had to take him sleeping. For if Roosevelt had been awake, there would have been a fight."