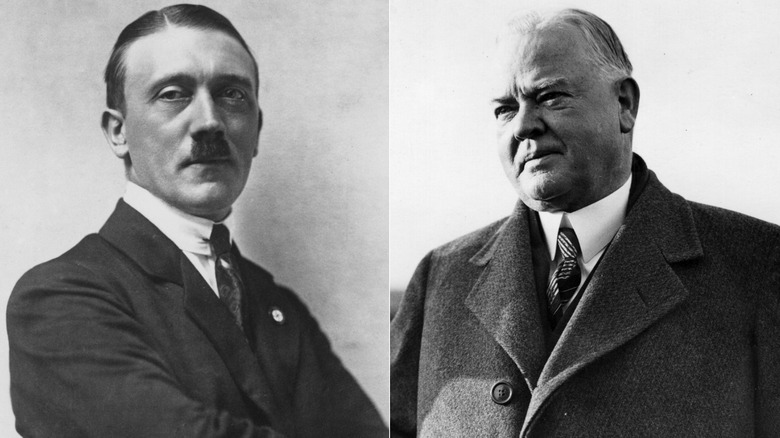

What Hitler's Meeting With Former President Hoover Was Really Like

Herbert Hoover remains one of the better-known presidents of the United States, though not for the reasons a head of state would wish. Fairly or unfairly, the voting public held him responsible for the Great Depression, a stigma that remains attached to his name — even after decades of historical research has put the economic downturn and his efforts to fight it into context. Those relief efforts were stymied, in part, by Hoover's own ideological inflexibility and his poor political skills. His shortcomings as leader in an economic crisis were compounded by his bitterness in defeat. Incensed that Franklin Delano Roosevelt would not heed his advice on the Depression during the transition, Hoover called his successor a "madman" (via The Washington Post) and his New Deal policies "fascistic" (per the UVA Miller Center).

Hoover's hostility to the Roosevelt administration made little difference during the election of 1936, and his unpopularity made even many Republicans keep him at a distance. But Hoover had other ways to pass his time in private life, ways that did not feed hard feelings over his reputation. Before becoming president, he had worked strenuously on post-World War I European relief, and many European nations honored him during the 1930s. Overseas travel filled his schedule in those years.

One such trip, in 1938, brought Hoover to Germany and put him face-to-face with Adolf Hitler. It was the only time in his life that Hitler met a U.S. president, sitting or retired. It was an enlightening visit for Hoover — and an occasion for sensational, overblown headlines back in America.

Herbert Hoover was reluctant to visit Nazi Germany

Germany wasn't Herbert Hoover's final destination when he went to Europe in 1938. The German government invited him to visit while he was en route to Poland. It was a visit that demanded the attention of several key members of the Nazi state apparatus. Surviving paperwork, later auctioned off by Alexander Historical Auctions, reveals the details that went into preparing for Hoover's arrival, from settling on Adolf Hitler's personal residence as the meeting place for the pair to which members of government would receive the ex-president when he arrived.

Such preparations might have been for naught had Hoover followed his first instinct. He was reluctant to make a stop in Nazi Germany on his way to Poland. After leaving office, he was an outspoken critic of fascism and communism for the infringements both ideologies made against personal liberty. It was on such grounds that he conflated the Roosevelt administration's policies with fascism in the essay "The Challenge to Liberty." But he ultimately decided to accept the German government's invitation.

The Nazis tried to play on Hoover's dislike of FDR

Preparations for Herbert Hoover's visit to Nazi Germany were detailed by Otto Meissner, state secretary; Wilhelm Brückner, chief adjutant to Adolf Hitler; and Werner Kiewitz, a diplomat. Besides such details as where Hoover and Hitler would meet and what transportation the former president would need, these men and others dwelled on what the substance of such a meeting should be. Relations between Germany and the United States were souring by 1938, which frustrated the Nazi government's efforts to secure trade agreements. That America and Germany represented diametrically opposed forces — democracy and "Christendom" on one side and despotism and "new paganism" on the other — was also settling into a fixed notion even without the prospect of war on the immediate horizon (via Alexander Historical Auctions).

Meissner was briefed on all this by Lieutenant General Baron Bernd Freytag von Loringhoven, who submitted two sets of a report — "Freytag Legation Counsellor (Research)" — for Meissner and Hitler's consideration. They included not only a summary of the tensions between nations but also suggested talking points that could be used during Hoover's visit. One such suggestion concerned Hoover's well-known antipathy for the Roosevelt administration, both its head and its policies. Freytag recommended engaging Hoover on the subject of Roosevelt, drawing out his opinions and his complaints about the New Deal. The reports also outlined lines of attack on the New Deal, inspired by bank criticisms of the policies, and advised denying any attempted influence by Nazi Germany on such organizations as the American Federation of Labor.

Hoover offered qualified praise for Germany's recovery from World War I

Herbert Hoover arrived in Berlin in March 1938. His itinerary included a 40-minute private audience with Adolf Hitler and dinner with Hermann Göring. The former encounter, naturally, has drawn more interest from historians, and any study of the encounter is greatly aided by a summary of the meeting — based on translations of the discussion — held in the National Archives (via the Presidential Primary Sources Project).

Per the summary, Hoover began his meeting with Hitler on a positive note. He favorably compared the state of Germany in 1938 to what he beheld 20 years earlier after the end of World War I. "All was depressed and despondent then," the former president said, but he now found "a very hopeful, live atmosphere" throughout the country. He told Hitler that Germany's economic progress was being followed with great interest back in the United States, where the speed of Germany's recovery could not possibly be matched.

Such praise, however, was qualified. Hoover noted that America's slower pace at building programs and organizations to facilitate such rapid growth was due to the country's commitment to personal liberty. Per The Washington Post, Hitler replied that Germany couldn't afford to indulge such notions as it built itself up.

The press blew Hoover and Hitler's meeting out of proportion

The translation of Herbert Hoover's meeting with Adolf Hitler was not available to the public for several years after the meeting, and at the time, Hoover had little to say on the subject. "I never discuss the character of such private conversations," he told the United Press. But the press — taking their lead from Pierre J. Huss of the International News Service — widely reported that an anonymous source had divulged a contentious argument over ideology between Hoover and Hitler. Headlines and stories loudly proclaimed a "clash," a "verbal duel," or a "scouring" had taken place in which Hoover had fiercely defended the virtues of personal liberty against Hitler and Nazism. The claims were denied by both parties, and the translation of their meeting would later disprove the reporting. Huss, a German citizen, faced expulsion for a time.

There was some tension surrounding the meeting, but it concerned a member of the press. Paul Smith of the San Francisco Chronicle was with Hoover in Germany, and Hoover requested that the journalist accompany him to the meeting with Hitler in place of another individual. The request was denied — officially because it was too late to change such arrangements. More likely, Smith was refused because his newspaper often featured harsh criticism of Nazism. Smith would later speak with Huss about the meeting, and the National Archives says it was Smith who first planted the framing of Hoover and Hitler's meeting as a heated debate.

Hoover was opposed to American intervention in World War II (before Pearl Harbor)

Herbert Hoover may not have given Adolf Hitler a stern talking-to over liberty, but he did take with him some strong impressions of life under Nazi Germany that reinforced his hostility to fascism. That the Nazi regime's harshest realities were hidden from him during the trip was obvious, he told a group of Stanford teachers (via the Presidential Primary Sources Project). A visit outside Berlin, to the outskirts of Germany where intellectuals confided in him, confirmed this. The rest of his European tour didn't offer any solace. "He came back [from his European trip] thinking Europe was in a morass," biographer George Nash told the Hoover Institution.

But with all he had seen, Hoover was still strongly opposed to any U.S. intervention in another European war. Most of all, he didn't want America involved in a European war that would ally the U.S. with Soviet Russia, even against fascism. Hateful of both ideologies and convinced that another war was coming, Hoover hoped that a war between Germany and Russia might see Hitler and Joseph Stalin finish each other off. Hoover did not believe that Hitler would choose to strike the West when so much of his rhetoric was aimed against the East, and even as late as 1941, he opposed American involvement and the Roosevelt administration's lend-lease offer to the Soviets. It was only after Pearl Harbor that Hoover came out in support of America's entry into World War II.