The 10 Worst Generals Of World War I

While all wars are horrible, World War I stands out as particularly terrible for everyone involved. Some have argued it was not just the worst war, but the worst catastrophe ever experienced by society. It was certainly the catalyst for many of the other terrible events of the 20th century that would follow, not least World War II. Thanks to new ways of killing that were in wide use for the first time — including the machine gun and poison gas — the number of dead soldiers was staggering. During the months-long Battle of the Somme, over 1 million British and Germans were killed or injured. The first day of that battle, July 1, 1916, is still the deadliest day in British military history, with almost 20,000 soldiers killed and nearly 40,000 injured.

The vast majority of the people killed had no control over battle plans or tactics. The blame falls to the men in charge, whose screwups led to the deaths of thousands. Just like World War I is complicated, so too are the reputations of some of these generals. In some cases, historians have debated how much blame they deserve for the war's various disasters, or if their successful actions outweigh their failures. In other cases, though, no one has ever tried to defend the incompetence of these military leaders.

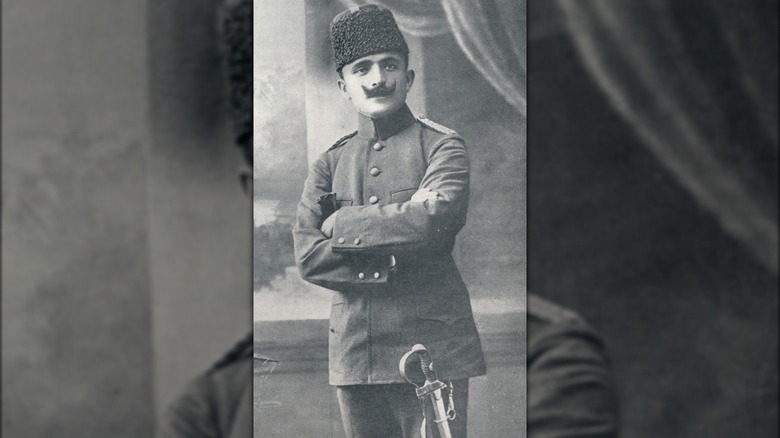

Enver Pasha

Enver Pasha effectively appointed himself head of the Ottoman military days before World War I began. This was his first mistake, as he couldn't see what those around him did, namely that he was terrible at everything to do with the military. This became clear when he ordered a winter attack on Russian forces, instructing his troops to leave their tents and even coats behind so they could march faster. The resulting casualties in the Battle of Sarıkamış crippled the Ottoman forces.

But the worst thing Enver was responsible for during World War I was the Armenian Genocide. United States Ambassador Henry Morgenthau wrote about some of his conversations with Enver in his memoir "Ambassador Morgenthau's Story." Enver was unapologetic, claiming that the realities of wartime required him to exterminate the Armenian people: "The Armenians had a fair warning of what would happen to them in case they joined our enemies. ... While we are engaged in such a struggle as this, we cannot permit people in our own country to attack us in the back. We have got to prevent this no matter what means we have to resort to."

Another time, when Morgenthau tried to give Enver plausible deniability by implying it was those beneath him who were really to blame for the atrocities, Enver was incensed, insisting, "I have no desire to shift the blame on to our underlings and I am entirely willing to accept the responsibility myself for I am convinced that we are completely justified in doing this ..."

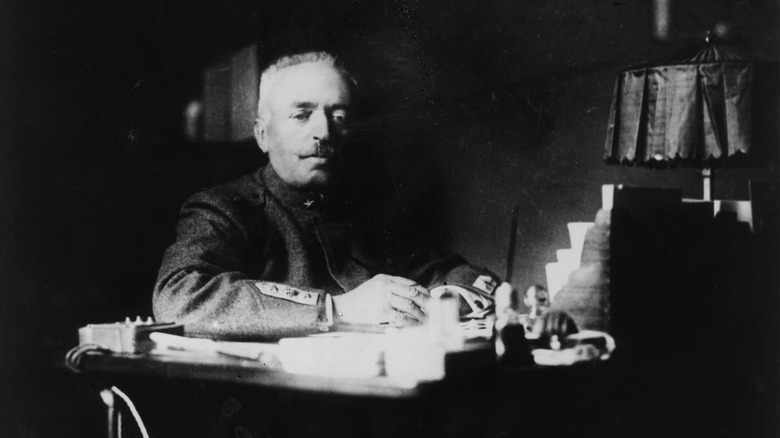

Luigi Cadorna

Historians do not argue over if Luigi Cadorna was a good or bad general in World War I. Not only was he bad, he's considered one of the worst people ever to lead an army in all of history. Cadorna had been about to retire in 1914 but instead became head of the Italian military when the former holder of the post inconveniently died mere weeks before the first shots of the war were fired. This meant he was in charge of hundreds of thousands of active-duty soldiers, despite never having been in combat himself. Nor was he a gifted tactician who had just missed out on battle — during wargames only three years before, he'd received very negative feedback on his tactics even in pretend conflict.

This incompetence met reality during the war, with Cadorna managing to lead almost two-thirds of his army to be killed or captured by 1917. He never won a major battle, and somehow managed to fail at the same battle multiple times. Part of the problem was the fact his troops were based in the Alps, but his own beliefs on warfare did not help matters, especially since in a war where firepower was everything, he was more old-school in his beliefs that manpower mattered more. Despite this, he was cruel to his own troops, including meting out discipline that included the death penalty for an estimated 1,000 soldiers.

So why did he get the job at all? His famous dad had been a successful general decades before.

Douglas Haig

While the Englishman Douglas Haig was on the side that won the war, his legacy is considered mixed at best by historians. The 1915 Battle of Loos saw a complete disaster for the British Army when they released poison gas — and managed to gas themselves. While arguments have been made for this decision being the fault of various commanders, in the end, the decision and even insistence that gas be used in that battle came from Haig.

It was also Haig who was primarily responsible for the tens of thousands of British casualties on the first day of the Battle of the Somme in 1916, effectively trying to advance by throwing his men at machine guns. For this, he gained the nickname "The Butcher of the Somme."

Then, in 1917, Haig decided to lie, or at least selectively withhold information, from his superiors in order to get them to agree with his attack plans for the Battle of Passchendaele. The resulting quagmire was just that — months of men fighting in mud and rain and failing to complete any of the goals Haig had for the conflict. It didn't help matters that his plans would have had a better chance as a surprise attack, but instead, he prepared his forces for weeks on open land where the Germans could see them. After months of fighting and 275,000 dead soldiers on the British side, Haig decided he could call it a victory despite making virtually no gains at all.

Paul von Hindenburg

Paul von Hindenburg was known as a steady hand and easy to work with as an officer, but it was his victory at World War I's Battle of Tannenberg in 1914 that made his name in Germany. After that, he was an icon, and was eventually promoted to field marshall. However, despite his successes, he also was responsible for the decision that brought the U.S. into the war. While there could be arguments over whether Germany could have won at all by that late point in the conflict even if the Americans hadn't shown up, what is sure is that they never could have once the U.S. did.

Yet despite knowing this, Hindenburg pushed for the tactic of unrestricted submarine warfare. This meant not only attacking military vessels but also civilian and commercial ships in the Atlantic Ocean — including those with American citizens onboard. "The Germans were well aware that the U.S. could not and would not accept unrestricted submarine warfare, but launched it anyway," University of Rochester professor Hein Goemans said on the school's podcast. "The U.S. declaration of war was thus already taken into account when the final decision for unrestricted submarine warfare was made in January 1917. Indeed, Hindenburg explicitly admitted the day before 'We count upon war with America.'"

Hindenburg made the wrong decision, but at the time he felt it was the only one. As his country's path to victory narrowed, he believed unrestricted submarine warfare was the only way to win the war for Germany.

Erich Ludendorff

Erich Ludendorff had various successes for the German forces under his control when World War I began and soon received several promotions. Eventually, he would become what was for all intents and purposes a military dictator. (It is not surprising that after the war Ludendorff found like-minded people in the young Nazi party.) He worked alongside Paul von Hindenburg, who tempered the many negative qualities of the younger soldier. He was nervous, angry, hated Germany's civilian leadership, and began enforcing an early version of "total war" on the country's population. (After the war he would literally write the book on the subject).

Ludendorff supported Hindenburg's push for unrestricted submarine warfare, which would end in disaster when it caused the U.S. to join the war, but he made his own mistakes as well. By late 1916, Ludendorff set his sights on winning the war in two years, so he began planning a major defensive campaign believing he could defeat Allied troops before American soldiers could ruin his plans. However, his plan to break enemy lines failed completely, and he offered to resign. The war ended a month later.

After the war, Ludendorff became obsessed with figuring out why Germany lost, while at the same time trying to take credit for any successes. He settled on the theory that he would have won if not for the traitors in his midst, an idea that the Nazis would use to their advantage.

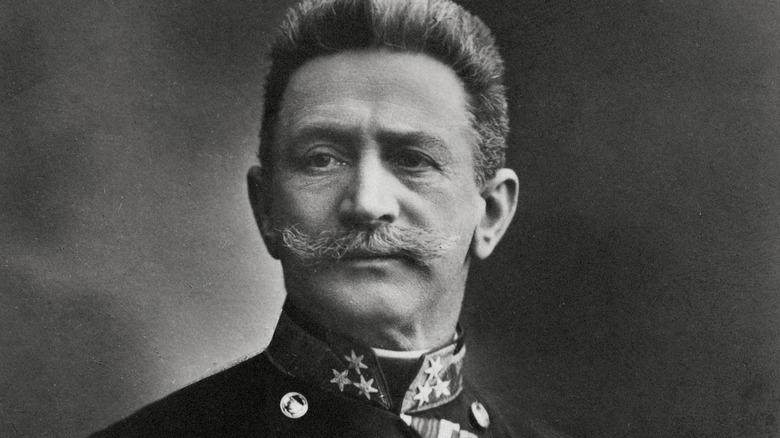

Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf

Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a member of Austria-Hungary's royal family, was assassinated in Sarajevo in 1914 — the event was the catalyst for the beginning of the war a month later. In answer, Franz Conrad von Hötzendorf initiated an attack on Serbia. The problem was that he knew his country's military wasn't prepared for a war, ignored this fact, and then his attempts at rapidly mobilizing the troops were a chaotic disaster.

Once the fighting began, Conrad's mistakes continued apace. Attacking Serbia was put on hold so Austria-Hungary could assist Germany in holding off Russia when they entered the war on the Eastern Front. Conrad decided to change the field positions of his Austro-Hungarian troops, but after this new version was already being carried out he changed his mind back. This confusion resulted in soldiers walking up to 100 miles in the summer heat to reach their destinations, rather than riding in trains as the original plan would have allowed for if it had simply been followed from the beginning. The exhausted troops were hardly an effective fighting force against Russia after that and were badly served by the elderly Conrad's old-school war tactics. Taking the offensive on all fronts against an enemy with better weapons meant far higher casualties for the Austro-Hungrarians than were necessary, especially since Conrad was fine forcing his soldiers to engage with much larger enemy forces.

Considered too difficult and ruthless as a leader by the time a new emperor took the throne in Austria-Hungary in 1916, Conrad found himself demoted from the military's top job.

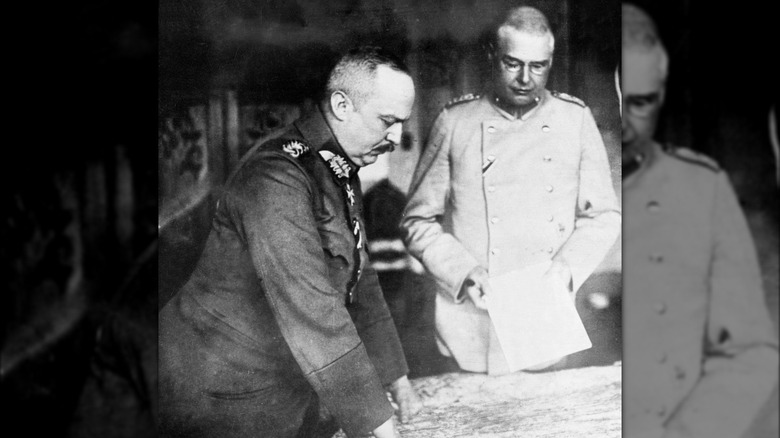

Helmuth von Moltke the Younger

Helmuth von Moltke the Younger (pictured right, with Kaiser Wilhelm II) saw World War I coming and knew who would be fighting in it. This prediction was made easier, however, because he was determined to make that war happen. As early as 1913, he stated that in a coming war between his country — Germany — and France, "We shall stop at nothing to gain our end. In the struggle for existence, one does not bother about the means one employs" (via "The Origins of World War I," edited by Richard F. Hamilton and Holger H. Herwig). And less than a month before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914, Moltke said of the already-tense situation in Europe, "If only things would finally boil over — We are ready; the sooner, the better for us" (via War in History).

Despite his bluster, Moltke wasn't actually sure Germany would win the war he wanted so badly. When it came, the fact that he'd only gotten his job because his uncle was a famous military commander became quickly apparent. He couldn't make decisions, didn't understand tactics, and was responsible for Germany's almost immediate defeat at the Marne in September 1914 when he sent 80,000 troops away to fight Russia instead of France as planned.

Demoted for his failure, Moltke wrote, "It is dreadful to be condemned to inactivity in this war which I prepared and initiated," as per "Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War," by Max Hastings."

Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich

Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich looked the part of a military commander (pictured right, with Tsar Nicholas II). This did not, however, translate into actually knowing how to command a military. Nevertheless, a family connection to the tsar and his popularity with the average soldier saw the duke put in charge of Russia's forces at the beginning of World War I. Despite having served in the military his whole adult life, the duke was shocked at this promotion and allegedly cried before taking over the role in 1914, knowing he was in over his head. In 1915, his inability to do the job was still apparent to both his own staff, and the tsar removed him from command.

However, others felt he was a good leader and that, ironically, his inability to force the generals beneath him to do what he wanted actually helped Russia by allowing flexibility at important times in the fighting. Nor did it help that Russia faced a munitions shortage and that the duke was forced to work from other people's plans for the war, both of which were out of his control.

His biggest failures were in allowing — and even encouraging — his soldiers' raping and pillaging of civilians in the areas the military controlled. The duke was also complicit in pogroms and mass deportations. His own officers were not spared, with stories of his personally and viciously disciplining them. He even ensured at least one was executed on questionable charges of espionage.

Denis Auguste Duchêne

Denis Auguste Duchêne was not popular with his fellow commanders. A difficult personality, the Frenchman did not treat his equals or even his superior officer with respect. However, it was not until these tendencies resulted in the deaths of thousands of soldiers and the loss of a battle that it became a real problem.

In 1918, the Allies were preparing to fight the Third Battle of the Aisne. This late in the war, even the most stubborn generals had learned from the mistakes of the past four years. Commanding Gen. Henri-Philippe Petain drew up plans for the battle and made a controversial decision. Rather than traditional tactics, they would copy how the Germans were doing things, namely, they would have soldiers in a position that was deep rather than wide. Duchêne did not agree with this decision — to be fair, many of the Allied commanders did not — especially since it would mean giving up hard-fought territory gains, which could demoralize the troops.

Duchêne decided not to follow this plan and instead decided to make British troops under his command spread out wide in thin lines. This would mean they were on the front lines in trenches that were falling apart and unsanitary. The British generals below Duchêne failed to get him to change his mind and follow Petain's instructions. During the battle, the British troops who had been forced to follow the flawed plan were hit hardest, with an entire corps almost completely wiped out.

Djemal Pasha

Djemal (also spelled Cemal) Pasha was one of the three Pashas controlling the Ottoman Empire during World War I, but he managed to carve out a little empire-within-an-empire for himself. For most of the war, he was not only a general but the governor of Syria. There, and in neighboring areas, he managed to terrorize civilians just as much as any of his armies could. He confiscated food supplies, deported families he didn't trust, and crushed dissent.

It was not only the locals who suffered under Djemal; his troops did as well. In fact, many of those soldiers were originally local civilians whom the pasha forcibly conscripted into the military. In Jeruselum, most were put in hard labor camps rather than being sent to fight. When these tactics led to men deserting every chance they got, Djemal had five of them seized and publically hanged. It appears that Djemal deliberately sent people he believed to be traitors to particularly dangerous areas on the front lines in the hopes they would be killed. He also led a disastrous attempt to take control of the Suez Canal, which saw 10% of his forces killed and made him a laughingstock.

While Djemal had plenty of atrocities laid at his own feet, he was angry about getting any blame for the Armenian genocide. Before his assassination in 1922, he wrote a very self-serving memoir of the war in which he claimed to have actually helped the Armenians, while others ordered their extermination.