The Untold Truth Of America's WWI German POW Camps

While the United States originally stayed out of World War I, the beginning of 1917 saw Germany push the country's lawmakers to the limit, including sinking several ships that led to the deaths of American citizens. So, during the first week of April, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war.

Months later, on November 16, 1917, Wilson released Proclamation No. 1408, which restricted the movements of Germans in the U.S. and forced all of them to register with the government, among other requirements. It also stated that "all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of the hostile nation or government, being males of the age of fourteen years and upwards, who shall be within the United States, and not actually naturalized, shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured, and removed, as alien enemies." In other words, just being a German man or teenage boy was now enough to get someone locked up.

Thousands of people would find this out the hard way when they were detained over the course of the next year. While not all of them had official POW status, whether they were civilians or military, they ended up in the same handful of camps across the country — and some of them never left.

Many POWs had already spent years in limbo

While the U.S. didn't declare war on Germany until 1917, some German citizens in America and its territories had already been dealing with the effects of the conflict for years. That's because the U.S. wasn't strictly neutral in the war they weren't fighting: They were definitely rooting for the team Germany was playing against. So when hostilities broke out in Europe in 1914, some Germans were probably surprised to find themselves in the wrong place at the wrong time.

This included the crew of the SS Cormoran (pictured), which was forced to dock in Guam when its supplies ran low. The U.S. territory didn't have enough provisions available to make it to safer waters, so the German sailors ended up living on the ship for years under the watchful eye of the U.S. military. It wasn't all bad; they got along well with those on the island while it was stuck there. But once 1917 rolled around and the U.S. and Germany were officially at war, the captured sailors were treated as hostile enemies, and the Cormoran was deliberately sunk by the Allies, killing seven German soldiers. The survivors were ultimately transferred to camps in the U.S.

Nor were they the only ones: Sailors on German ships that were docked in New York City, Boston Puerto Rico, and even Panama were also detained in various facilities for years while the government figured out what to do with them. In the end, it was decided that isolated, purpose-built camps were the solution.

POWs were held at three military camps

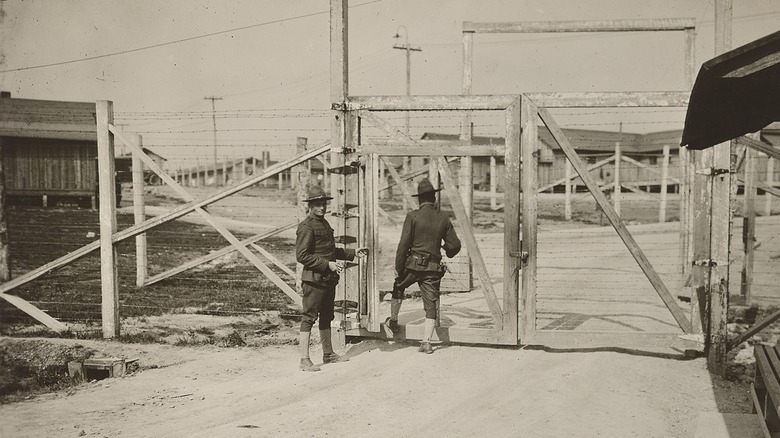

The U.S. government didn't really know what to do with the German prisoners it found itself saddled with. There had been no POWs in the country since the Civil War over half a century before, so there wasn't an obvious place to hold them. In the end, three locations were repurposed as POW camps under the jurisdiction of the military: Fort Oglethorpe and Fort McPherson in Georgia, and Fort Douglas in Utah.

All three locations had existed prior to the war, but they did not have the necessary facilities to house hundreds or thousands of prisoners. So the first act of business was to build them, with the labor being supplied by the prisoners themselves. Once they built their own detention camps, the Germans were also charged with maintaining them for the remainder of the war.

While there was plenty of anti-German sentiment at the time, in general, the locals didn't mind having a POW camp built in their backyards. In Utah, the camp was seen as a lucrative way to bring money into the state, so much so that when prisoners were moved from there to the Georgia locations in 1918, Utahns were furious that their slice of the war machine pie was being taken away from them.

Some civilian Germans were held at a former resort town

In theory, the three military bases were only going to house official POWs, that is, enemy combatants. While this didn't end up being the case, it meant that at first another location was needed to house Germans who were detained but by no stretch of the imagination were involved with anything martial. These included everyone from college professors to newspaper editors to merchant marines. They did not qualify as prisoners of war but were categorized as civilian enemy aliens and therefore their detention was overseen not by the military but by the Department of Labor.

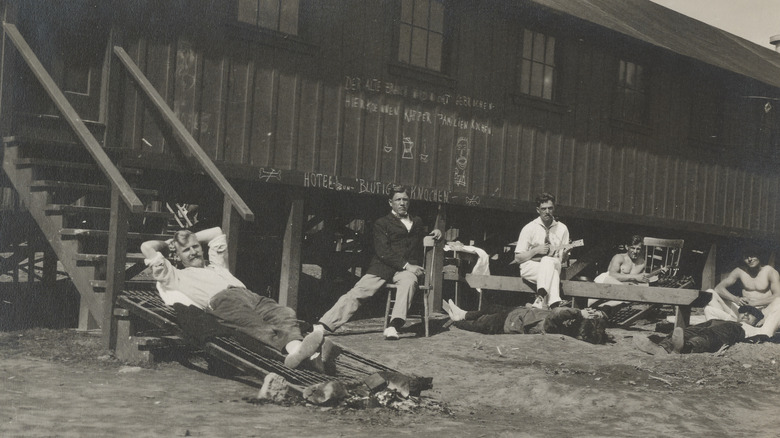

One of the locations selected for their detention camp was also not a military base but the isolated resort town of Hot Springs, North Carolina (pictured). The government rented out a hotel and its extensive grounds, which meant the Germans enjoyed not only beautiful scenery but also the use of amenities like a swimming pool.

The Hot Springs detainees also went much further than those in the other camps when it came to their construction projects. While they built barracks, barbed-wire fences, toilets, and other basic facilities like their fellow prisoners in Georgia and Utah, the crowning achievement of the North Carolina camp was an elaborate village reminiscent of those in their home country. The prisoners constructed German-style chapels, cabins, and even a swinging chair ride similar to those you can still find at county fairs.

Many of the detainees were there for ridiculous reasons

Despite the initial plans, civilian prisoners ended up being housed at other locations besides Hot Springs, North Carolina, which meant they were in detention with actual POWs. While almost none of the military prisoners had seen battle during World War I, they were at least tangentially related to the fighting by serving on sea raiders or auxiliary cruisers and could theoretically pose a security risk.

When it came to the civilians, though, there barely needed to be a reason for detainment. While the vast majority of Germans in America who were forced to register as alien enemies after the U.S. entered the war were never held captive, it was a danger facing all of them. The government did not engage in a mass roundup of Germans as they would later do to Japanese-Americans in World War II but instead went over each person's case to determine their danger to the country. This led to some truly head-scratching reasons for remanding the unlucky individuals to POW camps.

The conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, a German-born Swiss citizen named Karl Muck, was allegedly detained because he liked the music of Bach and once refused to play the U.S. national anthem before a concert. A search of poet Erich Posselt's home turned up a verse he'd written but never published that poked fun at America, which was enough to get him sent off to Fort Oglethorpe. And the banker Ernst Fritz Kuhn was determined simply to be too rich to stay at large.

Treatment was regimented but humane

One thing that stands out in contemporary reporting on the POW camps is how "humane" the situation was. The U.S. was keen to get that point across, now that it was sending its own soldiers overseas to fight, where they could be taken prisoner by German forces. By making it clear their POWs were being treated well, it was hoped this would be reciprocated. In general, this wasn't just propaganda but an accurate reflection of conditions in the camps.

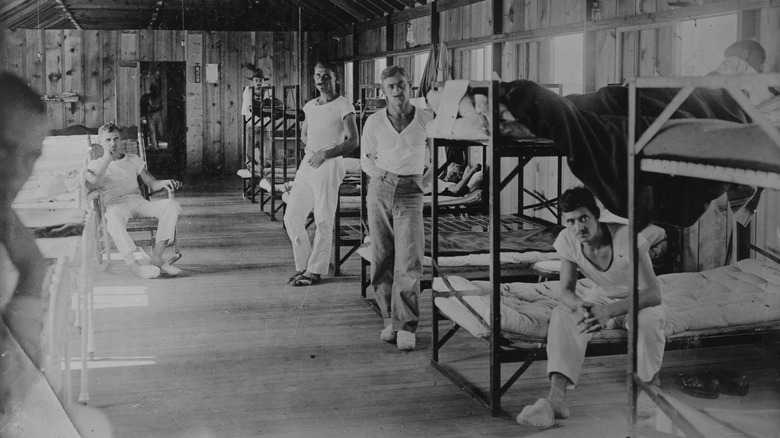

The POWs were woken up at 5:45 a.m. and most of them were expected to work an eight-hour workday. While they didn't get paid for maintaining the camp, they could earn wages for work done locally in the area. They were paid the same amount as locals for the same kinds of labor, and the money was theirs to keep. (Their wages were eventually cut — but only because Germany refused to pay U.S. POWs in their care a fair rate in return.) Their rations were no different from American soldiers, and the food at Fort Oglethorpe was prepared by imprisoned German cooks. Prisoners could also send and receive a limited amount of mail, although it was censored — which they particularly hated.

Nor was that the only complaint. While some were minor, there were plenty with merit and went all the way up to the detained Germans writing letters to Congress demanding to officially be granted the rights afforded to all incarcerated criminals, which many in the camps did not have due to their ambiguous status as alien enemies rather than POWs or even convicts.

The Millionaire's Camp

The overall standard of care for the prisoners in the camps was good, but for a select few it was even better. Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia was home to Camp A, more commonly known as the "Millionaire's Camp." While not all of the 90 or so prisoners held there were actually millionaires, they were men with enough money to pay the $25 to $35 per month that was required.

While nothing could make up for losing their freedom, the perks available at Camp A attempted to make it less painful. There were no long work days for these prisoners, at most they enjoyed a bit of voluntary labor in the private gardens surrounding their barracks. They were allowed to eat the produce they grew and could pay for their own food to go with it instead of eating normal rations; Camp A even had someone to play the piano for them while they ate. Inside their barracks, they had their own rooms, unlike the regular prisoners of Camp B who slept in dorms with little privacy or personal space. Other perks included bathrooms used only by the "millionaires" and the ability to hire other prisoners as servants.

After the war, the Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Karl Muck supposedly had only nice things to say about how he was treated at the Millionaire's Camp, although his letters and those of people who had visited him there showed that detention upended his life and destroyed his health.

Prisoners found many ways to ward off boredom

Being held captive is destructive to a person's mental state, no matter how nice their living situation is inside the gates. Many POWs suffered from what would become known as "Barbed Wire Disease," which led to mental breakdowns or suicide attempts. In order to avoid this, the POWs had dozens of ways to try and stave off the boredom, monotony, and stressful uncertainty of their confinement.

Active outdoor pursuits were favorites, with gardening and sports taking up a lot of the men's free time. Volleyball, tennis, handball, football, and more were played casually on any day, but there were also sports competitions planned well in advance that were taken extremely seriously. As one commandant explained in an official report, the "prisoners prepared themselves for the meets as though to contest with the champion athletes of the world. Every event was hotly contested" (via The Annual Report of the Secretary of War). The winners of these competitions even received prizes.

There were plenty of more intellectual pursuits as well. Fort Oglethorpe had enough world-class musicians and conductors confined there to hold regular concerts. Some of the prisoners started producing their own newspapers. A camp university was founded, and the professors who'd been lecturing at schools like Harvard and Yale before their arrests taught classes that were very popular with the prisoners. Every week there was a movie night, but the Germans also got into acting themselves, building a stage and putting on several performances of modern plays.

Issues included strikes and escapes

Overall, there were few major issues for the guards at these camps to deal with. Contemporary news reports said the commandant of Fort McPherson was happy with the attitude of his prisoners, who rarely gave him or his men trouble or even a harsh word. This meant he didn't have to punish them, knowing that this would have just made the situation worse for everyone. Even when he did have some troublemakers arrive — notably the crew of the SS Cormoran, who were angry they had been transferred to Georgia after originally being held in Utah — the punishment was individual rather than given to the whole group.

Fort Oglethorpe confined its difficult prisoners to Camp C, where they received disincentives like less food. They could be sent there for a variety of reasons, including refusing work duty or fighting with fellow prisoners.

Some of the POWs even attempted to escape. Successful escapes from the camps were rare, as all prisoners knew getting close to the barbed wire fences was basically a death sentence, but a few did manage it, including two men named Arnold Henkel and Jacob Breuer. Before July 1918, there were 29 successful escapes in total from the four POW camps, with 16 of those who got past the barbed wire having been recaptured by that time, while two others drowned in their attempts. That left 11 POWs who managed to escape and remain on the lam.

Women were not exempt from detainment

Proclamation No. 1408 only threatened to lock up men and boys, but women did not completely escape confinement for being alien enemies. They were required to register with the government, and some were taken into custody. In New York City, Rhoda Erdmann, an esteemed biologist who had been living in the U.S. and lecturing at Yale and Princeton, and Agathe Richrath, a German language professor at Vassar, were both arrested within days of each other on vague charges. (For example, Richrath was asked if she kept a picture of Kaiser Willhelm II in her room.) They were held at Waverley (also spelled Waverly) House, which was founded as a place for sex workers and women in need to get help but was taken over by the government to temporarily house alien enemies. The plan was to eventually send all of them to Fort Oglethorpe, where women-only barracks were being constructed, although this would never happen.

That didn't mean there weren't women in and around the POW camps. The men held there were allowed supervised visits with their wives once a week, something which many locals of Fort Oglethorpe were not happy about since it meant the German women moved to the area in order to be closer to their husbands. The Hot Springs locals felt quite the opposite, embracing the families who arrived there and managing to see them as not responsible for the actions of the German government and military.

Germans who died in the camps were buried locally

One of the worst incidences in the POW camps occurred in May 1918, when a guard at Fort McPherson shot and killed a prisoner during a game of baseball, apparently because the soldier mistook Heinrich Knappke running to catch a ball for an escape attempt. Knappke was buried at the local Marietta National Cemetery with full German military honors, in which the U.S. officers fully participated. Three other POWs who died at the camp were also buried there.

Most of the German POW deaths were not as dramatic as Knappke's; the main culprit was illness. The Hot Springs camp saw a bad outbreak of typhoid that killed 26 prisoners — on top of an additional 13 who died from other causes during their time there. They were all buried at cemeteries in the area. The 1918 flu pandemic also killed many POWs. At Fort Oglethorpe, 46 prisoners died of the flu in the fall of 1918 alone. Most of the 21 men who died while being held at Fort Douglas also succumbed to the pandemic. In 1933, a large memorial listing all of their names was erected in their honor, and they are still remembered with wreath-laying ceremonies on Veterans Day to this day.

After the war ended

The end of hostilities on November 11, 1918, did not mean the immediate end of internment for the German POWs in the U.S., something that came as a painful shock to them. In fact, it was not until the Versailles Treaty officially brought an end to the war six months later that the first prisoners were sent back to Germany from Fort Oglethorpe, and most wouldn't leave until the summer. A further 300 would be held at the camp all the way until April of 1920. Even if the POWs chose to stay in the U.S. after the war that didn't mean they got to leave any faster. Ironically, this meant the mood inside the camps got worse once the fighting was over.

It was a month after the armistice that Boston Symphony Orchestra conductor Karl Muck agreed to give the one and only concert he would conduct while in the camp. For the 3,000 or so prisoners who attended, it was world-class and magical. Despite being allowed to leave Fort Oglethorpe in May 1919, Muck refused. The stipulation of his release was that he immediately returned to Germany, and Muck was done being told what to do. He would leave the U.S. when he darn well felt like it. So he stayed incarcerated behind the barbed wire until July 1919, when he couldn't take it anymore. Then he and his wife sailed for Europe, where he continued to give concerts and be feted by music lovers. He never returned to the U.S. again.