What Peter Weinberger's Ransom Notes Really Said

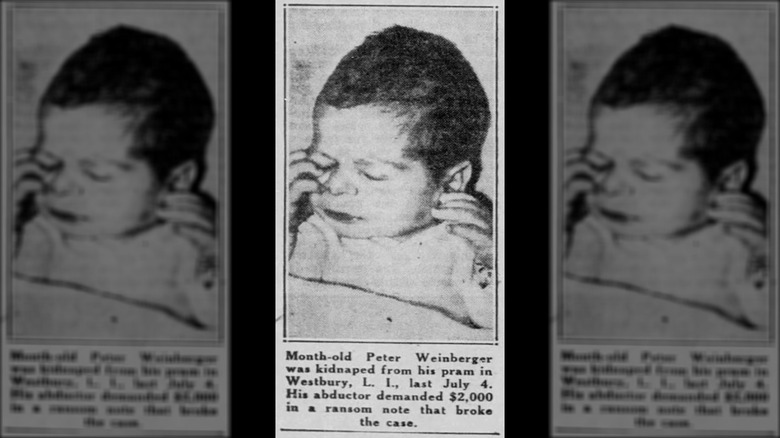

On June 4, 1956 in Westbury, New York, Betty Weinberger, a mother who had given birth a month earlier, wheeled her new baby, Peter, onto the patio of her suburban home, and left him there to rest in his carriage, under a mosquito net in the warm summer air. Peter was left alone for just 10 minutes, but when Betty returned to check on him, he was gone.

In his place was a ransom note. Peter had been kidnapped. What followed was a media scrum, a botched investigation, and the tragic death of the newborn, as well as the execution of his kidnapper.

The ransom note which set the whole affair in motion proved to be decisive in both how the kidnapping played out and how the kidnapper was apprehended. It also revealed a great deal of information about the kidnapper himself — far more than he had intended in his writing of it. Nor was the ransom note the only one the kidnapper wrote. Here is the story.

'I'm sorry this had to happen'

In the first ransom note, the kidnapper of month-old baby Peter Weinberger attempted to make it clear that he regretted his actions. Per Casetext, the note began: "Attention. I'm sorry this had to happen, but I am in bad need of money, couldn't get it in any other way."

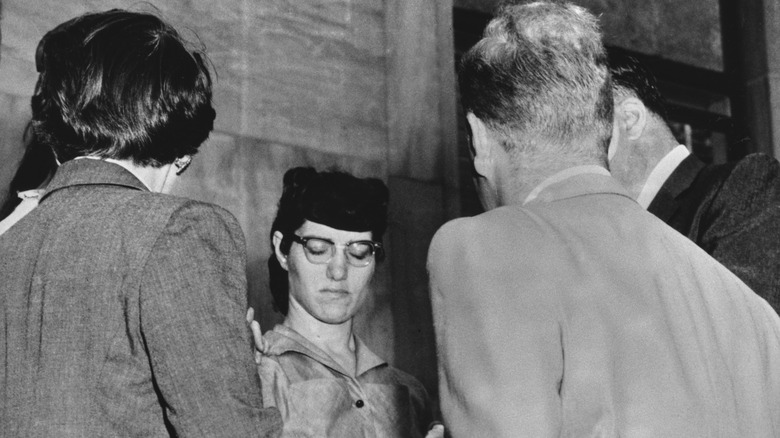

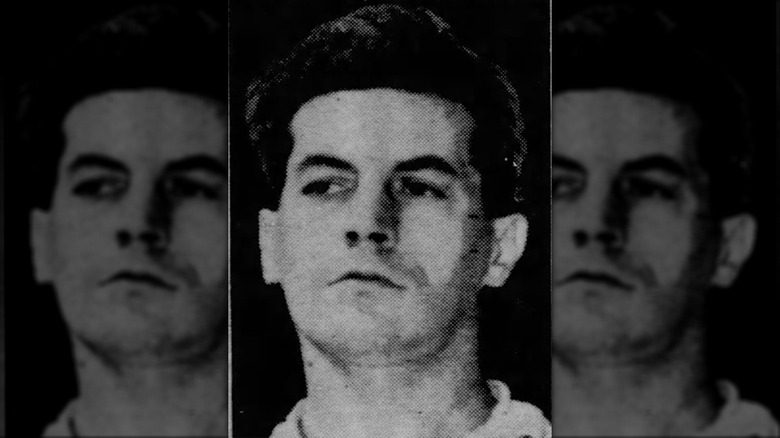

The writer of the note was Angelo John LaMarca, a 31-year-old married father of two young children. LaMarca had previously served in the U.S. military, but as the 1950s rolled on he found himself facing mounting debts, so much so that he would have to borrow money to take his wife, Donna (pictured), for dinner to celebrate their 10th wedding anniversary, which was two days after the date of Peter's kidnapping. Per a contemporary Daily News report (via newspapers.com) Donna testified at LaMarca's trial that her husband had been acting strangely around the time of the kidnapping, had been unable to sleep, and had been prone to displays of anger. Little did she know the terrible crime he had committed without her knowledge.

Though motivated by financial need, LaMarca would later plead insanity at his trial. He did so unsuccessfully.

'I am scared stiff'

Angelo John LaMarca was a desperate man, and it was obvious that he was aware of the severity of the crime he was committing, even in his first ransom note. Where in Hollywood movies ransom notes from kidnappers are typically cold and clinical demands, LaMarca's note left in Peter Weinberger's carriage betrayed the terror his kidnapper felt at potentially being caught.

"Don't tell anyone or go to the Police about this, because I am watching you closely," LaMarca wrote. "I am scared stiff, will kill the baby, at your first wrong move."

Nevertheless, Betty Weinberger and her husband Morris, decided to take their son's kidnapping to Nassau police, and the distraught family was soon visited by investigators who were stunned that a kidnapping could have occurred in the county. Despite requests for journalists to refrain from reporting on the disappearance, before long the story was splashed across the newspapers, in a turn of events that may have been at the heart of why the story had to end in tragedy.

'Two thousand, in small bills'

The American public had not been so horrified about the disappearance of a baby since the tragic kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr., the infant son of the famed pilot, back in 1932. The Lindberghs were incredibly wealthy members of the elite who tended to be the targets of such crimes by kidnappers looking to exploit those who they knew had access to vast sums of money. So the kidnapping of Peter Weinberger proved to be especially shocking as it was a crime that had befallen a normal middle-class family.

Angelo John LaMarca's ransom note instructed the Weinbergers: "Just put $2000 xxx (Two thousand, in small bills in a brown envelope, place it next to the sign Post at the corner of Albemarle Rd. Park Ave. at Exactly 10 o'clock tomorrow (Thursday) morning. If everything goes smooth, I will bring the baby back leave him on the same corner 'Safe Happy' at exactly 12 noon."

While LaMarca was in dire financial straits, the Weinbergers weren't exactly rich. Though they lived in an attractive house and Morris had a steady job as a pharmacist, they didn't have the funds available, and Nassau police — who believed the ransom should be paid for the safety of the child — and friends of the family had to come together to ensure the money was available. "No excuses, I can't wait!" the note concluded, signed: "Your baby sitter."

A repeat demand

But the drop off of the ransom money didn't go as planned. With word out that the ransom was going to be paid and that the kidnapper was assumed to be about to collect, police staked out the agreed drop-off location, or, rather, locations, as the drop location as described in Angelo John LaMarca's ransom note proved to describe two places on the same street.

By then, it wasn't just the police who were waiting to see who would come to claim the $2,000 ransom. Various members of the press were there, all looking to snap the first picture of the "Baby Sitter" kidnapper. But LaMarca never showed, and police assumed that the kidnapper must have been spooked.

Five days after the failed ransom payment, LaMarca called the Weinbergers (pictured) directly by telephone and demanded another drop-off. The $2,000 was deposited, but once more he refused to turn up. He repeated the stunt later the same day, and the Weinbergers were told that at the new drop-off, they would find a note informing them of where to find their son. However, when Morris Weinberger arrived at the location, he discovered another ransom note in a blue bag, which again demanded $2,000.

The notes revealed LaMarca's identity

At the time of Peter Weinberger's abduction, there was a federal law in place that prevented the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from intervening in a kidnapping case for seven days, after which it was to be assumed that the victim had been taken across state lines, allowing for a federal investigation. So after a delay of a week, the FBI was only just then able to put their manpower into identifying who had snatched the month-old baby, the wellbeing of which was becoming more of a concern with each passing hour.

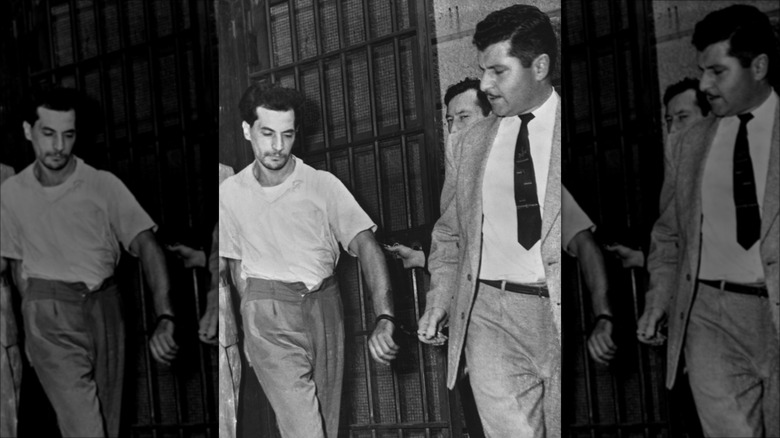

Agents combed millions of documents, per Newsday, in their search for a handwriting match for the ransom notes, which they knew was the key to identifying the kidnapper. They finally had a breakthrough on August 22, 1956, after which Angelo John LaMarca was arrested. Though he originally denied his involvement in the kidnapping, the evidence was damning, and LaMarca confessed. Two days later, investigators discovered the remains of Peter Weinberger at the site LaMarca said he had abandoned him. He had died of asphyxia, starvation, and exposure, with the Nassau County medical examiner suggesting that the newborn may have lived for up to a week after being abandoned.

Though LaMarca claimed insanity, he was found guilty of both the baby's kidnapping and his killing. He was sentenced to death by the state of New York, and died in the electric chair at Sing Sing prison on August 7, 1958. The law preventing FBI involvement in kidnapping cases until seven days had passed was later amended to allow for them to begin such investigations after just 24 hours.