Bible Mysteries That Remain Unsolved

Considering the Bible is based around some pretty mystical ideas, it's surprisingly grounded in reality in other ways. It says, for example, exactly how big Noah's ark was, what the Ark of the Covenant looked like, and has endless lists of who begat whom. Jesus gets four whole books that cover his relatively short ministry, and they include details about locations, family relationships, even clothing. But despite all the specific information, there is still room for plenty of mystery.

Sometimes the Bible just leaves out information that seems important and would be really helpful to scholars. Other times the information is there and made sense to readers at some point, but our understanding has been lost to history. Perhaps most famously, there are objects mentioned in the Bible that disappeared at some point, and people are still looking for them today. But despite all the interest, there are still plenty of biblical mysteries that haven't been solved.

Where is the Ark of the Covenant?

The Ark of the Covenant was an extremely fancy box used to hold the original tablets with the Ten Commandments engraved on them. It was supposed to have incredible powers, and killed anyone who touched it or looked inside (as seen in the documentary Raiders of the Lost Ark). But this unbelievably important and powerful object went missing when the Babylonians sacked Jerusalem in 587 B.C., and no one knows what happened to it.

According to History, one theory is that the Ark was moved safely to Egypt before the sacking. From there, it supposedly made its way to Aksum in Ethiopia. And that's where it is today. Mystery solved, right? Not exactly. While Smithsonian says a monastery in Aksum does claim to have the Ark (Ethiopians believe the Ark arrived well before the sacking of Jerusalem, brought back in secret by the illegitimate son of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba) no one gets to see it. Everyone just has to take their word for it. That includes, bizarrely, even the head of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church. The only person allowed to see the Ark is a single, virgin monk. After he is selected for this special position, he enters the Ark's compound (above) to guard it, then never leaves again. His job is to pray constantly and burn incense. He's there until he dies, when another guy gets the gig. The rest of the world is apparently never going to get proof one way or the other.

Where did the Lost Tribes of Israel go?

After Moses died, the Jews divided into a dozen tribes, each led by a different guy. Two of those tribes stuck around, but according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, the other 10 were conquered by the Assyrians in 721 B.C. Logic says the members probably just assimilated with the new group over time, and that's why they disappear from history as distinct entities. But there are modern people in far-flung places claiming to be direct descendants of some of these Lost Tribes.

Bible Odyssey says Richard Brothers wrote in 1794 that England was the home of the Lost Tribes, and he was their prophet. Despite the fact he was writing this from an insane asylum, a bunch of people got onboard with the idea. PBS says the Japanese as a whole are also supposed to be a Lost Tribe, as well as groups in China, Afghanistan, the Crimea, the Caucasus, Kenya, Zimbabwe (pictured), Nigeria, Armenia, Persia, Central Asia, North Siberia, West Africa, Peru, South America, Australia, and Ireland. The claim of a sect of Ethiopian Jews is taken seriously by Israel, and most of them live there now. Many people have said Native Americans are descended from the Lost Tribes, most famously Joseph Smith, who made it a key part of Mormon history.

The people with the most evidence they may be a Lost Tribe are a group of Jews in India. A genetic study in 2016 found they have some genes unrelated to other Indians, but similar to many Jews.

What year was Jesus born?

Theoretically, Jesus' birth year should be simple to pinpoint. Luke is very clear that Mary and Joseph went to Bethlehem because of a Roman census. He also says Herod was king at the time. According to Handbook for the Study of the Historical Jesus, there was a census in Judea in (what we now call) 6 A.D.; the only problem is Herod had been dead for 10 years at that point. Since the two events don't overlap, which one should be used to pinpoint when Jesus was born? Most Bible scholars pick Herod's reign and place Jesus' birth between 7 and 4 B.C.

The other Biblical clue to the time of Jesus' birth is the apparently extremely noticeable star that showed up. But as Historic Mysteries points out, there is no Greek, Roman, or Babylonian record of any weird astronomical activity during those years. If Jesus' birth is based on something happening in the sky, there are various other options. 12-11 B.C. is a possibility because of the appearance of Halley's comet. There was a local census at that time, and the historical record shows the comet was seen in the right area. Live Science reports there was another visible comet that was very slow moving 5 B.C. that was noted by Chinese observers. Or the star might not have been a comet at all. One astronomer argued the "star" was a conjunction of Venus and Jupiter in 2 B.C., while others say it was one between Saturn and Jupiter in 7 B.C.

What did Jesus do during his lost years?

The time between Jesus' birth and when he starts preaching around age 30 is virtually ignored in the four gospels. Obviously, lots of people throughout history wanted to know what Jesus did in those "lost years." There is absolutely zero evidence, but that didn't stop some individuals from coming up with outlandish theories.

SBS found despite coming from a working-class family in the Middle East, Jesus sure seemed to like to travel, allegedly going everywhere. One archaeologist wrote a book promoting the theory that young Jesus made it all the way to the Western Hemisphere, visiting tribes in "Peru, South and Central America, Mexico and North America." Another legend has it that at 21, Jesus came to Japan to study with a Buddhist master.

But there are two big theories out there. The first was put forward by Nicolas Notovitch, a Russian who visited a Buddhist monastery in the Himalayas and claimed he saw proof Jesus traveled to India, Nepal, and Tibet to study with yogis. Notovitch wrote a book about it in 1894, and people freaked out. But others have claimed they verified it since then.

English poet William Blake wrote "Jerusalem" in the 1800s, and it was turned into a popular hymn. It recounted the legend that Jesus came to England with his uncle during his lost years. But not everyone thinks it's a fairy tale. The BBC reports in 2009 an academic wrote a book saying it was "plausible" and Jesus had "plenty of time" to make the journey.

Where is the Holy Grail?

Even though it doesn't make much sense anyone would think it was important to grab and save a cup used by a random itinerant preacher at a random Passover meal, people have always been obsessed with the Holy Grail. It became a common theme in medieval literature, and legend had it the Grail was buried in England by Jesus' uncle or taken from the Holy Land by the Knights Templar. The stories hardly stop there, however; the BBC reports more than 200 places in Europe alone claim they are in possession of the one true Grail. (If you're outside Europe, don't worry, you might have it, too. Other claimants can be found in Nova Scotia and Maryland, for example.) A cup in Valencia, Spain, (pictured) is usually the one given most legitimacy and got more clout when two recent popes used it in religious ceremonies.

But this is an argument that is still very much ongoing. As recently as 2014, a new cup was declared to maybe, possibly be the Holy Grail. According to History, two historians argued a different cup in León, Spain, fit the bill. Scientific dating showed it was the right age, and it resembled the description of the Grail included in medieval Egyptian parchments. It was allegedly given to the king of Spain and held in the Basilica of San Isidoro from the 11th century. Since the 1950s, it had been sitting in the basement. So, is this one the real Grail? We will probably never know for sure.

What day did Jesus die?

Everyone knows Jesus died on Good Friday; the problem is the Gospels don't even agree on what day that is. According to Christianity.com, this was because the authors were more concerned with symbolism than accuracy. That's why, as the book Jesus, Interrupted points out, in three of the gospels, Jesus dies on Passover, but then John goes rogue and says he died the day before Passover. Scholars don't even agree if he died on a Wednesday, Thursday, or Friday.

Some geologists aren't letting the Biblical disagreement worry them, and say they have the exact day down. NBC News reported in 2012 that the researchers based their idea on Matthew's description of Jesus' death, which brings on an earthquake: "The earth shook, the rocks split, and the tombs broke open." So they analyzed the seismic activity in the area at the time. They found there was an earthquake sometimes between 26 and 36 A.D. This overlaps with the years Pontius Pilate was procurator of Judea, so it fits with what the Bible says. Once they added in the rest of the Biblical clues, the geologists found a few dates that work, and settled on Friday, April 3, 33 A.D. as the most likely, although it's impossible to know for sure. Three of the gospels also mention it going dark in the afternoon during the crucifixion, so the researchers also planned on looking into dust storms related to the seismic activity to pinpoint it further, although it's not clear what they found on that one.

What happened to the lost books of the Bible?

The Bible wasn't codified until about 400 A.D. Before that, there were lots of books considered holy or important by both Jews and Christians, and some of them didn't make the final cut. We have plenty of these books today, but others never got a chance because they are completely lost to history. The only reason we know about them is because books that did make it into the Bible mention these works.

According to Reluctant Skeptic, there are 22 of these lost books (although Bible Review says some may be the same thing under different names, so there could be as few as half a dozen). Over and over again in the Old Testament, an author will casually be like, "and of course you can find this information in X book," only we don't have X anymore. From what the Bible tells us, these lost books include the histories of various kings and prophets, genealogies, and songs (similar to Psalms). The Book of the Wars of the Lord, as explained by the Jewish Virtual Library, sounds especially fun: an epic poem all about how God destroyed the various enemies of Israel.

But there may be an even more important lost book not included on the list. Ancient Pages reports many scholars think two of the gospels were written based on information from a previous work, known as the Q source. While it's an extremely controversial theory, proof of Q would be one of the most important discoveries ever.

How is God's name pronounced?

Judaism has strict rules about the personal name of God. According to the Jewish Virtual Library, while there isn't a rule about writing God's name down, there is a prohibition against erasing or defacing it in any way. To make sure this couldn't happen, his name just wasn't written down. A rule also developed that Jews couldn't say God's name outside the Temple. Then the Temple was destroyed, so that effectively meant no one could say it, ever. Since it couldn't be written down either, this was a problem. Scholars passed down the correct pronunciation for a while, but eventually, everyone forgot how to say their god's name.

The Encyclopedia Britannica says when God revealed his personal name to Moses, it was written down as YHWH. This is called the tetragrammaton. But because of how Hebrew works, that doesn't tell us how to pronounce the name correctly. Early Christian writers used something similar to Yahweh. Then Latin-speaking scholars came along and had another problem because "y" doesn't exist in Latin. They replaced it with an "i" (also used for "j," which Latin also doesn't have), and people started pronouncing the tetragrammaton as Jehovah, which was definitely wrong. It wasn't until the 1800s that scholars switched back to Yahweh, but again, that's probably not right, although it might be closer.

So according to Jewish tradition, their god (who is also the god of Christians and Muslims) has a personal name that he totally told humans once, and no one knows it.

Who was the pharaoh in Exodus?

The pharaoh in the Book of Exodus is a real jerk. Moses nicely asks him to let his people (the Jews) leave Egypt, and the guy refuses and punishes the Jewish slaves. So Moses brings down the wrath of God, there are a bunch of horrible plagues, and eventually the pharaoh gives in. But even then, he changes his mind and tries to make the Jews come back, so Moses has to part the Red Sea and the Jews finally escape. But the Bible fails to mention the name of said pharaoh. Since there are no Egyptian records of this event (which, according to National Geographic, doesn't automatically mean it didn't happen, since pharaohs were not in the habit of recording their losses) historians and religious scholars don't know who it was.

There are theories, of course. The name that usually come up, especially in movies about Exodus, is Ramses II. This is based on very scant clues in the Bible about the Israelites building cities for the pharaoh. Ramses had some building projects that would fit the bill. Plus, the first mention of "Israel" as a place shows up during the reign of Ramses' son. That means the Jews must have left by then, possibly quite recently.

But not everyone agrees on Ramses II. In the Jerusalem Post, one scholar uses various bits of evidence from the Bible to place the Exodus around 1330 B.C., smack in the middle of King Tutankhamun's reign. So the debate rages on.

What does Selah mean?

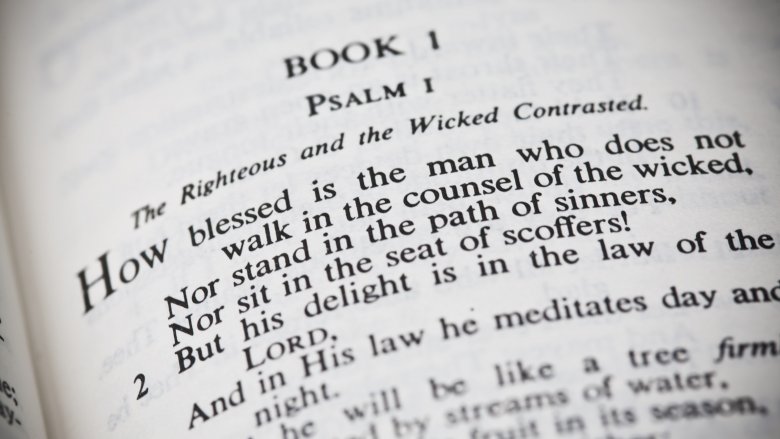

The Hebrew word "Selah" is all over the Old Testament. According to Ancient Pages, it's used almost 80 times, which means it's three times as common as "hallelujah" and twice as common as "amen." But while those words, also from Hebrew originally, are now used and understood around the world, no one says Selah. The writers of the New Testament didn't use it either, and that's because by the time they were writing, the meaning of the word was long forgotten. Even when people started translating the Old Testament from Hebrew to Greek way back in 270 B.C., they had to speculate on its meaning.

No one has figured it out since, either. As Christianity.com puts it, the true meaning of Selah is a mystery. There are plenty of theories. Since the word is used in Psalms so much, and since the Psalms were originally meant to be sung, scholars think it might be some kind of musical notation. Possible translations include "silence," "pause," "end," "a louder strain," "piano" (meaning soft, not the instrument), "intermission," or "a pause in the voices singing, while the instruments perform alone." A lot of those are a similar idea, but some modern versions of the Bible don't even bother trying to translate, just keeping "Selah" and assuming the reader will figure it out.

Good luck, because at least one music expert doesn't think the word is a notation but part of the lyrics, possibly meant to be closer to "amen" than any musical instruction.

Where is Ophir?

Ophir is often referred to as the Biblical El Dorado. According to New Advent, the Old Testament can't get enough of mentioning this amazing place. It comes up in Genesis, Job, Isaiah, 1 Kings, 2 Chronicles, and the Psalms. Sailors would go on three-year missions to bring back everything from gold, silver, and precious stones, to ivory and fancy woods, to apes and peacocks. These shipments were supposedly a large part of the reason King Solomon got so rich. Obviously, it would be great to know where this luxurious location was, but Ancient Pages says scholars have been wondering for 2,000 years.

Ancient Greek translators of the Old Testament placed Ophir somewhere in India, Sri Lanka, or the Malay Peninsula. Others have proposed various parts of the Arabian Peninsula. The Jewish historian Eupolemus placed it on an island in the Red Sea. But there's also evidence it might be in Africa somewhere, even though Africa is sadly lacking in peacocks. In 1871, a German geologist visited what is now Zimbabwe and announced he'd found ruins that were definitely Ophir, and his claim was supported by some other scholars at the time. The Roman mathematician Ptolemy and the Arab traveler Ibn Batuta both wrote about a place just as rich as Ophir in present-day Mozambique, while the Ancient Egyptians recorded information on the extremely wealthy land of Punt, most likely in modern Somalia. If both places were real, Punt and Ophir might be the same and might be in East Africa, but who knows?