The Untold Truth Of Chernobyl

Chernobyl was one of the worst human-caused disasters in the history of our world, a stunning example of what can happen when you combine arrogance, dangerous technology, and international politics. Now, more than 30 years later, HBO's miniseries Chernobyl is making us all relive the horrors of the Cold War and, more explicitly, the potential horrors of nuclear energy. But in the 1980s, the Soviet Union was an isolated place, and most of the information that came out of it was propaganda designed to make the Soviet Union look as awesome as possible.

So almost none of what the Soviets told the world about the disaster was the 100 percent truth, which means the rest of us were left to try and sift the truth out of the outright lies, half-truths, and honest accounts of the disaster, some of which emerged only decades after the damaged reactor was shut down.

So what do we know? The HBO miniseries, as it turns out, is pretty accurate. But all fictionalized historical stories are just that — fictionalized, at least in part, and you can't really watch the miniseries in order to discern the whole truth. What you can do is check out this list of the untold truths of Chernobyl, which should give you a pretty good start. Then you can watch the miniseries and decide for yourself what really happened and what is just leftover Soviet propaganda from 1986.

It was human error

If you were to imagine a likely scenario for a nuclear accident, you'd probably picture something going wrong deep inside the reactor, a glitch that spawned another glitch, that snowballed until the entire system broke down. Or Homer Simpson falling asleep at the controls. It's a lot harder to imagine a terrible accident that happened during routine maintenance — but that's exactly how the Chernobyl disaster went down.

According to Al Jazeera, on April 26, 1986, workers were testing the plant's No. 4 reactor to see how the cooling system might work under limited power. But first, they turned off the power-regulating system and the automatic shutoff system, you know, so they wouldn't be annoyed by all the safety warnings and other anti-explode-y interruptions. During the test, something went wrong. There was a power surge, which caused fuel pellets inside the reactor to explode, which in turn caused an explosion large enough to blow the roof off the reactor.

When air mixed with the carbon monoxide gas inside the reactor, it started a fire that burned for nine days. Meanwhile, a cloud of radioactive material exited the reactor and entered the atmosphere. And the Soviets went, "Craaaaaaap" and then a bunch of people died. Yes, the disaster was at least partly caused by people being stupid. Imagine that.

There aren't any three-eyed fish near Chernobyl

On The Simpsons, Springfield's lake is so contaminated with nuclear waste that the fish have three eyes. Because The Simpsons is where most of us get our information about the effects of nuclear radiation, you've probably imagined that the landscape and waters around Chernobyl — officially referred to as "the exclusion zone" — are similarly blighted: Full of three-eyed fish, six-legged deer, wolves that shoot laser beams from their eyes, and swamp monsters. And while National Geographic says there is some concern that mutations linked to radiation exposure could be passed down through generations of wildlife, the sorts of mutations seen in animals living near Chernobyl aren't the same caliber as multiple limbs and laser-beam eyes. "Mutated" animals might have developmental abnormalities, but any major mutations won't be passed on to successive generations simply because severely mutated animals don't usually survive long enough to reproduce.

Surely the Chernobyl accident must have had some impact on the local wildlife though, right? As a matter of fact, yes — it had a very strong positive impact. Say what?

It's not the radiation that benefited the wildlife; it's the fact that human beings fled the radiation, leaving the animals a human-free environment where they could flourish. One study concluded that "the benefit of excluding humans from this highly contaminated ecosystem appears to outweigh significantly any negative cost [to the ecosystem] associated with Chernobyl radiation." How's that for a silver lining.

Okay, there aren't any three-eyed fish ... that we know of

Not so fast, though. Everything is not totally rosy for the animals that live in the exclusion zone. According to the New York Times, some of the birds living there have malformations like abnormally shaped beaks. They might also have significantly smaller brains. On the flip side, many of them have an adaptation that leads to the production of antioxidants, which seem to help prevent genetic damage.

The trees in the exclusion zone grow more slowly, too, and there are fewer insects — populations of butterflies, bees, and grasshoppers appear to be diminished. So do spider populations, though frankly that seems like a big check in the positive column.

The animals that don't have any outward signs of radiation poisoning are still radioactive — wild boar, for example, have been found that have dangerous amounts of radiation in their bodies. Some of these radioactive boar have been discovered as far away as Germany. But probably the weirdest thing happening in the exclusion zone has to do with the decomposers, that is, the organisms responsible for breaking down organic matter. Things don't rot they way they're supposed to. In fact there were dead trees in the exclusion zone that even 20 years after the accident were still not decomposing. So wildlife may be thriving in the exclusion zone, but the exclusion zone is still a creepy horror freak show.

Most of the people who were exposed to the radiation had no long-term health effects

In the years following the accident at Chernobyl, we all assumed the worst. Two people died in the initial explosion, and the deaths that followed were bad. One hundred thirty-four people received dangerous doses of radiation and suffered from acute radiation syndrome — 28 or 29 of those people died in the first few months, and 19 more died as the years passed, although some of those deaths were unrelated to radiation exposure.

But according to Slate, we can't measure the real impact on the rest of the people who were exposed. Experts in 1986 predicted up to 40,000 cancer deaths, but that's only 1% of the expected cancer-related mortality rate for that population. So statistically speaking, the increase — if there is one — is impossible to measure. And really, there aren't that many people who got a dangerous dose of radiation. For most individuals, it was the equivalent of a couple CAT scans.

There was a dramatic increase in thyroid cancer among people who were exposed as children, and an increase in the rates of leukemia and cataracts among Chernobyl workers. But other than that, the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation says there wasn't a measurable increase in solid cancers among people who were exposed to Chernobyl radiation.

Chernobyl was one of only two INES 7 nuclear disasters

The severity of nuclear accidents is measured by the International Nuclear Event Scale, or INES. In 1998, the Hunterston B nuclear power plant in Scotland lost its connections to the electricity grid during a storm, and the reactors were left without forced cooling for about half an hour. Staff was able to restore power, and a serious incident was avoided. You've never heard of this event because it was INES 2, a mere "incident" on the scale of "no big deal" to "super-bad."

Three Mile Island, which you probably have heard of, was an INES 5 "accident with wider consequences." In 1979, the No. 2 reactor at the plant partially melted down, and roughly 2 million people received a dose of radiation equal to about 1/6 what you might get during a chest X-ray.

Only Chernobyl and Fukishima rated a 7 — the highest INES rating for a nuclear accident. Now, 7 doesn't seem so bad compared to 5, but the ratings are logarithmic, which means that a 7 is roughly 100 times worse than a 5. And just to put that into perspective, Chernobyl released about 100 times more radiation than the atomic bombs dropped on Nagasaki and Hiroshima, which means yes, it was literally worse than a nuclear attack.

Some people just didn't leave

You know how whenever there's a volcano that's about to explode, there's always some old guy who tells reporters, "I've been here my whole life and I'll be darned if I'm going to evacuate now!" And then the volcano explodes and buries his house in ash and he's never seen again.

Similarly, some people in the exclusion zone also refused to leave, or rather, they refused to stay gone. According to PRI, about 1,000 people, mostly older women, actually moved back into the exclusion zone not long after they were told to leave, and around 100 of them are still there, 30 years after the disaster. Most of these people had roots in the area — some families had been there for centuries.

At first, the evacuees were relocated to Ukranian cities, but they kept trying to go home until officials finally let them. It was widely believed they would all die, but hey, sometimes people would rather die than leave the only place they truly feel at home.

Weirdly, the women who went back to the exclusion zone appear to have longer life expectancies than those who did not — relocated people often suffer from alcoholism, unemployment, and the breakdown of their social circles. Or perhaps, not unlike the wildlife near and around Chernobyl, these people just thrive in a land free from the interference of (other) humans.

The Soviets might have forced pregnant women to abort

No one really knew what the long-term effects of all that radiation would be, and many people feared the worst — to the point where pregnant women were terminating their pregnancies because of a fear that their babies would be born with mutations. According to The Social Impact of the Chernobyl Disaster, there were even women who lived well outside the exclusion zone who chose to end their pregnancies rather than run the risk of having an abnormal baby.

It's worse than that, though, if the rumors are to be believed. According to Women's E News, in their zeal to mitigate the effects of the disaster in the eyes of the rest of the world, the Soviets may have actually forced some pregnant women to obtain abortions. One woman who worked in the clean-up crew at Chernobyl told the crowd at a speaking engagement that she saw a "big can" full of late-term aborted fetuses while working on assignment in Pripyat, the town closest to the disaster site. She believes the Soviet government forced thousands of pregnant evacuees to abort. It's impossible to know for sure how much truth there is to the accusation, but given how much natural fear there was in the population outside the exclusion zone, it would not really be surprising to learn that there was some seriously disturbing stuff going on behind the scenes.

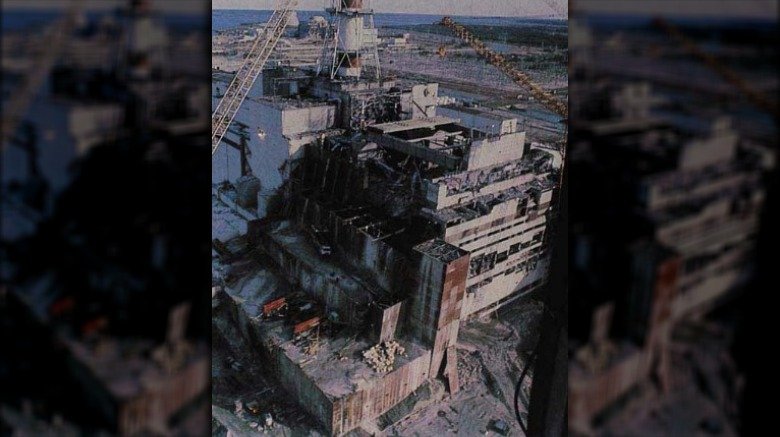

There's still some pretty scary stuff in that reactor

Well, at least they got it all cleaned up and nothing bad can ever happen at Chernobyl ever again. Except that they didn't actually get it all cleaned up. They didn't even clean up most of it.

According to Voa News, there are still 200 tons of uranium inside reactor No. 4, and for the first 30 years after the accident the stuff wasn't even very well contained. Shortly after the disaster, the Soviets built a "sarcophagus" around the reactor in an effort to contain the radiation, but it was never intended to be a permanent solution and work on a new one began almost immediately after the first one went up.

The original sarcophagus was built from 14 million cubic feet of concrete and took 206 days to complete — the new sarcophagus took 15 years to build and assemble and was so massive that it took 18 ships and 2,500 trucks just to transport it from Italy to Chernobyl. The new structure is expected to last 100 years, but it's still unsettling to think that the best way to clean up a nuclear disaster site like Chernobyl is to not clean it up at all, but just drop a giant piece of snapware over the top of it and hope it seals in all the bad stuff long enough for it to not be this generation's problem any more.

It will take thousands of years for Pripyat to become habitable

Speaking of generations, how many more generations will pass before people can safely move back into Pripyat? Well, according to the Christian Science Monitor, about 110. That's right, it will be 3,000 years before Pripyat becomes habitable, right around the time when your great, great, great, great, great (etc. until you get to 108 greats) grandchild is ready to buy his or her first home. That's a time scale roughly equivalent to the time between now and when rice was first cultivated in ancient Japan.

But wait, there are some experts who call that three-millenia window "optimistic." Ihor Gramotkin, director of the Chernobyl power plant said it would take "at least 20,000 years," which is way, way off from that 3,000-year estimate. That's 733 generations, or more like the time between now and when Homo sapiens first migrated to the Americas.

There's an elephant's foot in the basement

In 1986, workers discovered "black lava" inside a steam corridor underneath reactor No. 4. They dubbed it the elephant's foot, which is adorable except that unlike the foot of your kid's favorite pachyderm at the local zoo, this foot could deliver a lethal dose of radiation in about five minutes. According to Nautilus, at that time one hour of exposure to the elephant's foot would have been the equivalent of 4.5 million chest X-rays.

Ten years after the accident, the elephant's foot had tamed a little. It was still radioactive, but only about 1/10 as radioactive, so cool. Time to take tourists down there, right? Well if you have a rudimentary knowledge of math, you already know that tourism is still mostly out of the question — even 10 years after the elephant's foot was formed, standing next to it foot for just over eight minutes would have caused mild radiation sickness, and standing there for an hour would have caused death.

And the foot isn't just sitting there, either. It's still melting into the base of the plant. If it ever meets ground water, it could cause another massive explosion or it could simply leech radiation into the local water supply. So it's not like they can just rope it off and never go down there — someone has to keep an eye on it. Wouldn't want to be that someone.

The plant was still operating 14 years after the accident

Chernobyl had four functioning reactors. Before the accident, the Soviets were building fifth and sixth reactor units. Then after the explosion, Soviet officials went, "Welp, guess we won't keep building those other reactors!" But according to Business Insider, that change of plans did not include also shutting down the other three reactors. How optimistic.

Then in 1991 a fire damaged reactor No. 2, and it had to be shut down. In 1996, after reports of elevated rates of thyroid cancer started to reach the ears of the rest of the world, officials finally caved to outside pressure and shut down reactor No. 1. But Chernobyl still wasn't finished, and Ukraine stubbornly continued to operate the one remaining reactor until 2000, when international negotiations finally led to its shutdown.

It's easy to criticize the decision to keep the plant operating, but at the time it made financial and logistical sense — the Soviet Union lagged way behind the rest of the world in terms of infrastructure, and they simply needed those units running to meet the energy demands of their nation. And today the plant is shut down but not completely decommissioned, which means that Ukraine still needs to figure out what to do with all the depleted uranium and contaminated equipment.

This is all not so very easy to bring to the screen

The Soviet Union of the mid-1980s was a very buttoned-down place, much like North Korea is today. They weren't especially forthcoming to the rest of the world about their internal problems because they wanted the rest of the world to view them as a glorious, prosperous empire rather than the sort of place where nuclear accidents could displace 300,000 people. So it's not like they went, "Hey, world, our reactor just exploded!" And even today, the existing information about what happened at Chernobyl is less than trustworthy. So when writer and producer Craig Mazin went on his fact-gathering mission for the HBO series Chernobyl, he says he had to be cautious about which side of the story to tell because it's simply impossible to know which version is accurate. "I always defaulted to the less dramatic because the things that we know for sure happened are so inherently dramatic," he said on Variety's "TV Take" podcast.

According to the Washington Post, the people deemed responsible for the accident at the time now claim that they were made scapegoats by the Soviet government, which was desperately trying to cover up the fact that the reactor was poorly designed and enormously unstable. That means that no matter how hard the miniseries tried to be accurate, it could only ever be as accurate as its sources, and there are few guarantees. Still, even the toned-down version of events is horrible enough.