Things About Japanese Mythology They Didn't Teach You In School

Out of all the typical elements of ancient and modern Japanese culture that tend to tickle the imaginations of folks across the world — feudal samurai, ninja, anime, manga, Tokyo's neon lights, karaoke, sushi, etc., etc. — core Japanese mythology tends to get overlooked. That is, unless you're poring through Reddit threads and anime wiki pages or playing video games featuring embellished interpretations of mythological figures. In fact, we're not sure that anyone outside of diehard Japan fans and/or university programs has really delved into Japanese mythology in any legitimate, serious sense.

Japanese mythology is more a collection of odd vignettes and weird characters than any strictly regimented tome of unified tales. Folks in Japan generally don't distinguish between mythology, folklore, legend, and plain old backwoods tales. It's all blurred together, and commonly understood in the way that stories about Johnny Appleseed are known the United States. Even translated words like kami ("gods") or oni ("demons") don't convey proper meaning because they're tainted by Judeo-Christian meanings that have zilch to do with Japan.

All that being said, folks who are familiar with Japanese mythology know how wild, weird, and sometimes whacky it can be — even compared to other global mythologies. It's all patently idiosyncratically Japanese, and much of it isn't really suitable for children. A good chunk of these stories' details might get omitted if you learned about them school, like royal incest, maggot-covered dead people, anus-eating spirits, kidnapping, lots of bloodshed, and tons of lurking, horrific creatures.

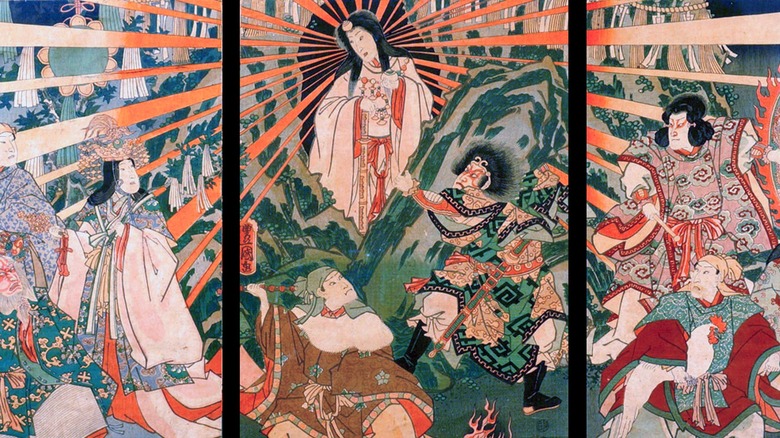

[Featured image by Utagawa Kunisada via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

Sexing the world into existence

First off, Japanese mythology is way, way, way (several more ways) too complicated to even begin to cover in detail here. But looking at the broad strokes: Folks will notice that much of Japanese mythology is tied to Japan's geography and physical landscape. The creation of "the world" involves the creation of the Japanese islands, particularly standout natural features like mountains and caves associated with particular gods and events. And of course, biological life being what it is, creation started with sex. Plus there are generations of incest, infanticide, the underworld, some "she-devils," eye washing that produced the moon, and ... Listen, just roll with it, okay?

Japanese creation myth focuses on the male essence Izanagi and the female essence Izanami, who sexed existence into being and were also brother and sister. They pushed a spear down from the sky and into the ocean and "stirred the brine till it went curdle-curdle" to make Japan's original landmass, per Sacred Texts. But, Izanami broke protocol by being the first to speak when they met, so their tryst wound up producing deformed children. They tried again the proper way, and presto: instant 14 islands of Japan. Some of these islands, it should be noted, were named things like Prince-Good-Boiled-Rice and Luxuriant-Sun-Youth.

Thus begins the birth of innumerable minor spirits, elemental gods like Kagutsuchi the fire god, the well-known sun goddess Amaterasu, and eventually the emperor, who was a living descendent of the gods. That's quite a family reputation to live up to.

[Featured image by Welcome Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0 DEED]

Golden boy, peach boy, and one-inch boy

Few things illustrate the WTF territory of Japanese mythology as the three children figures of Kintaro, Momotaro, and Issun-Boshi. In order, that's the red-skinned warrior child and masculine ideal, the boy that burst forth into existence from a peach, and the boy that was one-inch tall and used a sewing needle for a sword. All three are slayers of demons, all three are magical beings, and the latter two both come as unexpected surprises to couples without children.

Kintaro ("Golden Boy") is a revered, ruddy-skinned figure who's kind of like a Japanese Hercules. He was raised by a female ogre in the forest, performs feats of strength like wrestling with bears, is generally naked and chubby, wields an axe, and is a follower of the warrior Minamoto no Yorimitsu. In the modern day, Kintaro is a well-known, admirable, somewhat oafish figure who is revered on Children's Day to hope for strong male children.

Momotaro ("Peach Boy") is a straight-up magic child who floats down to Earth in a giant peach, lands in a river Moses — or Osiris-style, and is found by a woman who has to explain this all to her husband before Momotaro erupts from the peach to maraud some demons. Issun-Boshi, meanwhile, is a one-inch tall child born to a lonely elderly couple who travels around in a rice bowl boat using chopstick oars. He eventually rescues a princess by killing a demon who drops a Mallet of Luck that turns Issun-Boshi into a regular-sized person. Super Mario inspiration, much?

Yokai: horrific monsters and cautionary tales

Here's the scene: You're walking alone down a dark, secluded alley at night and a woman approaches you from the other direction with jet-black hair and a surgical mask over her face. She asks you, "Am I pretty?" If you say no, she whips out a pair of scissors and disembowels you. If you say yes, she pulls off her mask to reveal a Glasgow smile cutting her face from ear to ear. She asks her question again, and if you say no, she cuts you clean in half. If you say yes, she gives you a Glasgow smile, too. This is kuchisake-onna, aka, "the slit-mouthed woman," and she's just one yokai — spirit, often malicious — out of hundreds from Japanese mythology.

Technically speaking, yokai can be benign or just mischievous. Not gods, not demons, not ghosts, they occupy a hazy middle ground of reality. They act on instinct more than anything else, which often goes wrong for humans. Other examples include the 100-eyed creature todomeki posing as a little beggar girl in robes, the obariyon who wants a piggyback ride from forest travelers and promptly gnaws on your scalp, the woman-headed serpent nure-onna who prowls dangerous waters, blood-sucking jubokko trees that house the bones of their victims, and frog-like kappa who pull people into water and eat their anuses (yes, really). There's a clear cautionary pattern in all this madness: Be careful while venturing into nature and be doubly careful of strangers.

[Featured image by Welcome Images via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY 4.0 DEED]

Global myths: unite

Even though Japanese myth has its own obvious quirks, it shares many mythical archetypes — and even specifics of particular stories — with other ancient mythologies across the world. Not all of these similarities are disturbing, but the disturbing parts definitely wouldn't make the elementary school cuts of such tales. Take the tried-and-true Orpheus and Eurydice tale from Greek myth. Eurydice dies, Orpheus goes to get her from the underworld, and he's allowed to escort her out provided he doesn't look back at her. When he does eventually look back Eurydice is trapped in the underworld forever.

The Japanese version features the aforementioned creator gods Izanagi and Izanami. Inazami dies and Izanagi goes to the underworld to get her. But, because she's already eaten the underworld's food she can't return to the world of the living. Things get gruesome when Izanagi finds Izanami decaying and infested with maggots. Izanami shrieks at her former lover and summons an army of grotesque lady demons from the land of the dead to go after him in a harrowing chase in which Izanagi eventually escapes the hags by throwing magical peaches at them.

Other examples of similarities between Japanese mythology and other global mythologies include dragon-slaying legends, even a multi-headed dragon similar to the Roman hydra. We've got heroic feats performed by heroes, kings proving their right to rule through ancient lineages, deities of the sun, and more. Izanagi and Inazami are even brother and sister like Zeus and Hera.

Tengu: long-nosed mountain forest spirits

There's so many more examples from Japanese mythology that we could go into that our last choice for this article is almost arbitrary — almost. Tengu, however, stand out above other elements of Japanese myth because they're so ubiquitous and actually more grounded than other, more whacky tales. Tengu are also taken very seriously, even nowadays. People in Japan still sometimes make offerings to them at shrines in the woods in order to ask for peaceful relationships with the natural world. So yes, Tengu are representatives of nature. They're morally ambiguous, shape-shifting, sword-wielding, part-human and part-animal spirits with attributes like dogs and birds who abduct unwary travelers.

Oddly enough, the standout feature that all Tengu share is their nose, often portrayed as long and thin, almost like Pinocchio's. Some have taken this depiction to mean that Tengu originated in tales of non-Japanese visitors to Japan, especially because Tengu skin is typically depicted as darkish red. This time around, however, we can trace this particular mythological creature back to a precise origin: 7th-century stories from China regarding ill omens and shooting stars dubbed "tiangou." Fast-forward through time and this general sense of ill omen morphed into goblin-like forest entities positioned as enemies of the civilized world. Unlike other yokai, Tengu are also ardently anti-Buddhist. Some, therefore, relate Tengu to pre-Buddhist Japanese beliefs in tree spirits that fused with later, imported stories and religions. Either way: Show some respect if you venture into the woods in Japan, and maybe bring an offering, too.