Grim Details About The Deadly Hammond Circus Train Wreck Of 1918

In the late 19th and early 20th century, before the age of the internet, TV, and even cinema, one of the biggest spectacles American people could ever hope to see was a traveling circus. Circuses were first developed as equestrian shows by former dragoons in the U.K. in the late 1700s. But a century later they had come to offer all kinds of entertainment, from jugglers and clowns to circus animals and their trainers. Circuses also spread across the globe, becoming especially popular across Europe and America.

There were soon almost 100 active circus troupes traveling the U.S., some boasting rosters of performers, crews, and animals numbering in the hundreds. And despite the traditional image of circuses traveling from state to state in a convoy of packed circus wagons, by the late 1800s the rail network across America was so advanced that even the biggest circuses in the country were traveling to their audiences by train. But the early days of rail were also incredibly dangerous, with the first railroad accident taking place in 1832. Decades later, railways criss-crossed the U.S. from coast to coast but still had little oversight in terms of safety, with frequent crashes taking the lives of hundreds of people a year. And one of the deadliest train accidents in American history involved a circus troupe: The Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, which in 1918 was decimated in the Hammond Circus Train Wreck which took the lives of 86 people and injured 127.

[Featured image by East Oregonian Newspaper via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

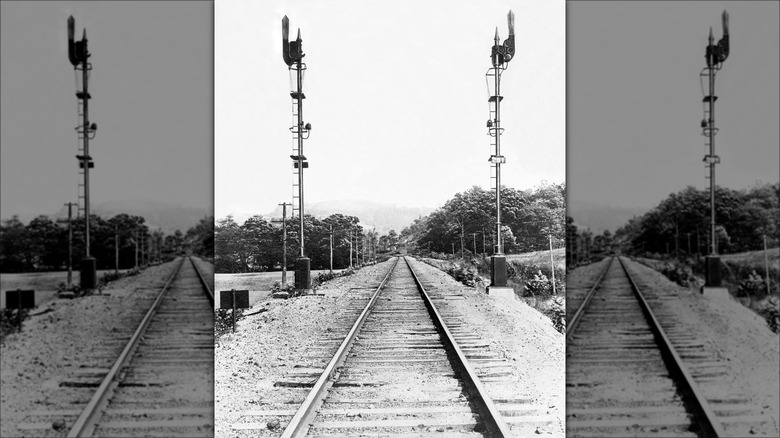

Missed signals that led to the Hammond Circus Train Wreck

The Hammond Circus Train Wreck took place on June 22, 1918. It was around 4 a.m., and the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus was traveling through Indiana from Michigan City on the way to its next scheduled performance in South Chicago. The troupe operated a circus train that housed their performers, with the animals kept in a separate segment. There were 58 rail cars in total, with 1,000 people in total employed by the circus including performers and other roles, though they traveled from place to place in waves rather than together. The segment of the train containing the animals had already gone ahead, following the early crews that included billposters and lithographers, and a press agent.

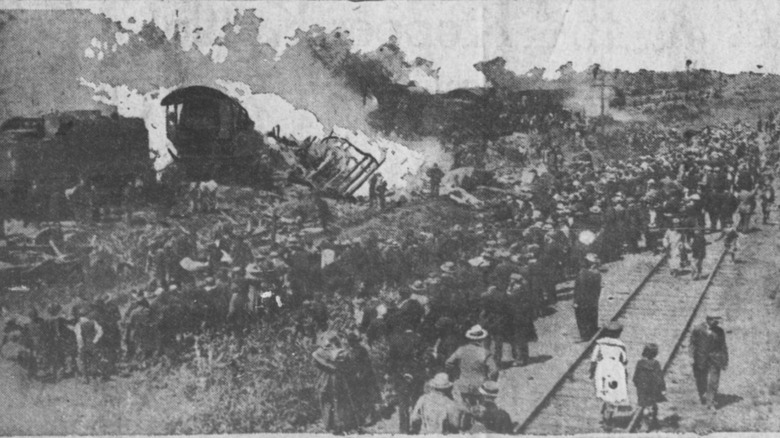

The section containing the performers was following behind as they ordinarily did, but on this occasion it was forced to travel slower than usual because the engine's headlight was out. Around Hammond, the train was still on the tracks when an engineer named Alonzo Sargent, who was driving a heavyweight steel train over the same stretch of railroad, failed to notice several signals warning him that there was another train blocking his path. His train slammed into the caboose of the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus train, obliterating it with such force that one of the survivors of the disaster told the Chicago Tribune that "it parted in the center as clean as though it had been sliced with a giant knife."

Wooden carriages and kerosene lamps

Trains were developing at quite a speed in the early 1900s. And by the time of the Hammond Circus Train Wreck, many of the models built during earlier decades were growing obsolete. Those operated by the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus were around 30 years old at the time of the disaster, which made them even more fatal for passengers in a crash.

The carriages in question were constructed entirely from wood, which was quickly torn asunder as the colliding train plowed through the caboose, mangling the carriages and splitting apart the beds in which the performers slept. Scores of people died on impact, and within seconds those who survived found themselves at the center of an inferno. The kerosene lamps that lit the carriages set the remnants of the train ablaze, burning to death many of those who were trapped in the wreckage and barring attempts to rescue survivors.

[Featured image via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled]

Charred remains and shifting blame

The victims of the Hammond Circus Train Wreck were in many cases so badly burned by the fire that spread through the wreckage that their bodies could not be formally identified. However, the identities of those missing included some of the circus' star performers — Millie Jewel, the "Girl Without Fear" who worked with animals; aerialist Jennie Ward Todd; and Arthur and Joseph Dericks, brothers who performed in the circus as strongmen. Joseph Coyle, the circus' leading clown, also lost his wife and two children in the disaster.

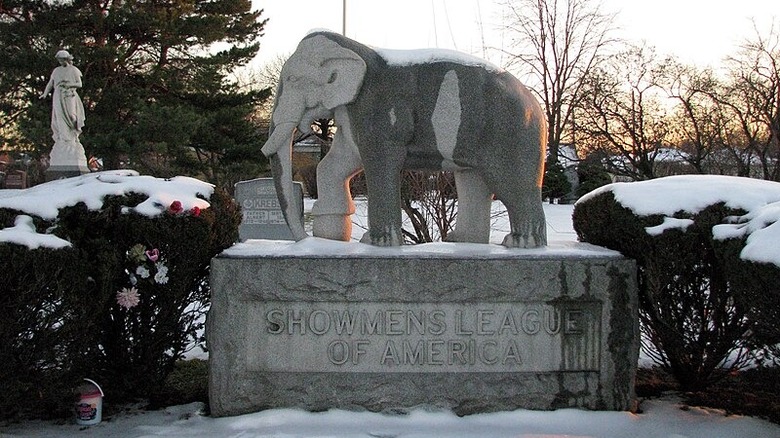

The recovered bodies were taken to Chicago's Woodlawn Cemetery. There, the bodies were interred in a large plot secured by the Showmen's League, a community of showpeople founded five years earlier to provide scholarships, financial aid, and memorials for performers in the amusement industry. Fifty-three bodies were buried in the plot, but sadly only five were identifiable by name. A stone elephant marks the site, which can still be visited today.

Alonzo Sargent was charged with manslaughter, but a mistrial ultimately saw him walk free. In the wake of the disaster, little was done to identify what systems were to blame for the mass deaths, or whether the circus itself was in any way liable. Instead, circuses and other traveling troupes were urged to switch to steel carriages for the safety of their passengers. A month later, another train wreck involving two passenger trains in Nashville, Tennessee took the lives of more than 100 people, prompting greater safety checks across the board and the gradual phasing out of wooden carriages.

[Featured image by 6th Happiness via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 3.0]