Secrets They Didn't Want U.S. Citizens To Know About Three Mile Island

Never doubt humankind's ability to wipe itself off the face of the Earth. Sure, it hasn't happened (yet!), but there are a million ways it could.

Some sort of nuclear apocalypse is perhaps one of the easier — and more horrifying — disasters to imagine. Between a Doomsday Clock set only a few minutes from midnight, the hundreds of nuclear reactors worldwide, and the gross incompetence of how the Soviet Union handled the Chernobyl meltdown, as recently depicted on the HBO series ... well, a catastrophe never feels too far away. While Chernobyl was the worst of the worst, though, it's worth mentioning that the United States had its own royal mess-up: the 1979 nuclear meltdown at Pennsylvania's Three Mile Island. The situation never quite escalated to the level people were afraid it might, but the public relations disaster was one for the books. Here are secrets the government and the plant operators tried to keep hidden about the nuclear disaster at Three Mile Island.

Don't just blame the machines; there was human error involved at Three Mile Island

When you compare Three Mile Island and Chernobyl, people in the Western hemisphere often spout platitudes about how Chernobyl was caused by people doing stupid things in a corrupt system, while Three Mile Island was just an unavoidable technical error — because, you know, Americans would never mess up so dramatically, right?

Not really. According to Stanford, the inciting incident that took place on March 28, 1979, started when the nuclear power plant's pump system, which provided water to cool the reactor, became clogged. This increased the pressure, so a relief valve automatically opened up. That's good. Not so good? The valve didn't close back up, which caused one-third of that valuable cooling water to drain out. Now, while you can blame that one on the machinery, the bigger problem was that the human plant operators didn't notice it. Furthermore, they also overlooked the fact that the emergency feed water valves were closed for routine maintenance. Without wading too deep into the technical details, what you need to understand is that because these people didn't react in time, cooling water flooded out, the temperature rose ... and boom, the nuclear reactor went into a partial meltdown while also creating a big, scary hydrogen bubble inside the reactor.

So, to be clear: Yes, the Three Mile Island situation, both on a technical and human level, went colossally better than Chernobyl, but that's just luck. It very easily could have gone just as badly, or worse.

Speed of molasses

So, at 4:00 a.m., the partial meltdown happened at Three Mile Island. Not the sort of circumstance you want to encounter on the night shift, that's for sure. Alarms blasted in the control room, according to the Washington Post, as radiation flared inside the containment shell ... but nobody leaped into action to seal off the structure. Instead, this was done by an automatic mechanism later, when even the system realized "okay, this is real bad." But hey, at least someone alerted the authorities, right?

Wrong. According to History, it wasn't until 7:00 a.m. (a full three hours later!) that the staff dialed up local and state authorities to let them know that, hey, a nuclear reactor was melting down in their backyard. Twenty-four minutes after that, an emergency was declared. That was good progress, but the officials continued stalling. Instead of telling the locals what was going on, or maybe ordering an evacuation of the surrounding towns, the situation was downplayed. Spokespeople for Metropolitan Edison, the plant's operating company, mounted a quick public relations campaign to make sure nobody freaked out. Even more obnoxiously, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission went public a day later, claiming that the danger had passed. It hadn't — in fact, it was getting worse by the hour — but they kept that to themselves.

Not everyone bought the story. At a press conference, a Metropolitan Edison official actually had his microphone yanked away by a local mayor named Robert Reid, who demanded to know why the nuclear situation had been kept private for three hours. Good question.

Officials got a different story about Three Mile Island than the public did

Okay, so at this point, if you were the average Pennsylvania local, all the big officials were trying to calm you down. At various press conferences, TV appearances, and interviews, these folks promised you that everything was cool, the danger had passed, and that you could just go to work and not worry about it. Sure, a nuclear meltdown sounded awfully scary, but apparently the right people had swooped in and rescued the situation before anything bad could happen. Great.

Behind the scenes, the conversation was drastically different: In fact, those officials were busy discussing whether they needed to evacuate the same 600,000 people they had just falsely reassured outside. By the night of March 29, according to History, further inspection of the reactor found that it was more damaged than previously estimated. Even worse, a hydrogen bubble was growing within the reactor, threatening to burst. As these dangers grew increasingly ... dangerous, officials eventually relented a bit on their comforting message, suggesting that locals within a 10-mile radius should maybe, you know, "stay inside." Hmm, as if nuclear radiation doesn't penetrate windows? Even as the situation worsened, it's been reported that Governor Dick Thornburgh had to be dragged "kicking and screaming" to the decision of advising women and young children to take a long-distance vacation.

Nobody had plans for how to handle the emergency at Three Mile Island

Unless you're in the Marvel Universe, nuclear radiation is dangerous. Everyone knows that. So you'd think that all the responsible parties in charge of Three Mile Island would have prepared a detailed plan on how to respond to a potential disaster, way beforehand ... you know, in case something like a meltdown happened, and people needed to evacuate.

Nope. History writes that Three Mile Island had no evacuation plan. Just straight up nothing. Despite the fact that five nearby counties were at serious risk, neither Metropolitan Edison nor anyone else involved had ever considered the importance of so much as a pitch meeting to consider potential evacuation ideas. So by the time Three Mile Island did melt down and that hydrogen bubble looked ready to pop, the top officials desperately tried to draft some evacuation plans at the last second ... which, yeah, might be the ultimate example of why "winging it" is not a good management technique. Meanwhile, as the authorities scrambled to get things together, the general public got fed up with the nonsense. Approximately 40% of the bystanders living within 15 miles of the power plant packed their bags and hit the road, without being ordered to do so. Smart thinking, but this unofficial evacuation got every bit as chaotic as you'd expect.

The official response (and lies) about Three Mile Island were a bigger crisis than the meltdown itself

Risk communication isn't easy. You're probably going to get details wrong, and people will be upset about it. However, as Power Magazine explains, the officials at Three Mile Island broke the single most important rule of effective crisis PR, which is that you should always err on the alarming side.

Sure, if you blow the siren, evacuate the population, and then come back and awkwardly admit that you overreacted, people will be annoyed. But you know what's worse? Underreacting, saying everything is fine, and then repeatedly having to tell the public, over and over again, whenever the situation ends up being worse than you anticipated. The nuclear meltdown at Three Mile Island happened on March 28, and according to History, it wasn't until April 4 that Metropolitan Edison admitted to the public that, uh, well, that hydrogen bubble was a big problem. Sorry, folks. By this point, obviously, no one trusted them anymore.

In the end, Three Mile Island ended up not being the catastrophe some feared it could become, but the secretive response of the authorities was, indeed, catastrophically bad. These days, the handling of the whole thing is looked back on as a textbook example of how not to react to a nuclear crisis.

Radioactive gases were vented into the atmosphere from Three Mile Island

Once clean-up was underway, Three Mile Island's auxiliary building rapidly became like an inflated balloon, ready to pop from the explosive levels of gas building up inside it. Short of using a giant science fiction vacuum cleaner, this meant that these gases had to be released, according to the Washington Post, to prevent an explosion from occurring. Guess where the gases were vented? That's right: directly into the atmosphere. Sure, why not, who cares? Now, you can imagine how people reacted to the news that a radioactive gas named Krypton 85 was being vented into the air, especially after being lied to for quite a while. Nobody in Pennsylvania trusted the assurances of Metropolitan Edison that these small, radioactive steam emissions were "safe." In fact, the Environmental Protection Agency reports that local anti-nuclear protest groups directly petitioned the U.S. District of Court Appeals to get the venting process halted, arguing that they wanted a public hearing on safety. The appeals court denied this petition, and the venting proceeded as planned.

Was it safe? On the official books, to this day, no one died from Three Mile Island. However, decades later, a number of uncomfortable alternate possibilities have emerged into the light.

The cancer cover-up at Three Mile Island

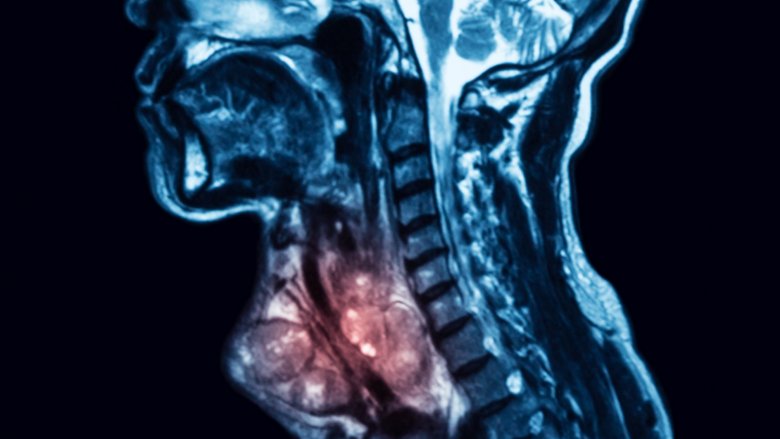

As anyone familiar with the Chernobyl disaster can tell you, radiation does some horrifying things to the human body. Acute radiation syndrome, cancer, deformities ... it's scary stuff. Now, the official stance of the nuclear industry is that there's no conclusive link between the Three Mile Island incident and nearby cancer cases, but according to Penn Live, some local doctors see it differently. Pennsylvania medical professionals report a higher incidence rate of thyroid cancer, which is often caused by radiation, in the area near the power plant. Call that hearsay if you want, but here's an uncomfortable truth: The CDC's numbers show that Pennsylvania has one of the highest rates of thyroid cancers in the country.

In 2017, USA Today reports that research was finally conducted on the matter. Led by Dr. David Goldenberg, the study found that while much of the thyroid cancer in Pennsylvania was seemingly not caused by radiation, the cancer patients who had been exposed to low-dose radiation in nearby counties at the time of the Three Mile Island meltdown gave off a mutational signal indicating that radiation was the cause. On average, these people developed thyroid cancer 11 years earlier than the average patient.

While this merely shows a correlation, rather than causal proof, it does point toward the believable possibility that the vented radiation from Three Mile Island may have caused damage to people's lives ... damage that higher-ups would rather leave hush-hush.

Going to court over Three Mile Island

Nobody was happy with the way Metropolitan Edison handled the situation. Not the people, not Pennsylvania's politicians ... and least of all, the federal government. After three years of federal investigation into the matter, the New York Times says the company was indicted on multiple counts. The allegations were that management had falsified data regarding a leaky valve, trying to dodge the necessary repair work that was needed on Three Mile Island's Unit 2 reactor. On top of that, they'd also destroyed documents. These charges were particularly centered around a man named Harold W. Hartman Jr., a reactor operator, who in a transcribed interview had reportedly told investigators that the valve's leak rate numbers ”had to be fudged every time we got, just about every time that we got it, we had to do something to make it right.”

Hmm, just the sort of thing you want to hear about a nuclear power plant accident, right? Anyhow, in 1984, the Washington Post wrote that Metropolitan Edison pleaded guilty to one count in the indictment and no contest to six counts.

A similar issue occurred a few years earlier ... and nobody paid attention

Honestly, the whole situation at Three Mile Island could have been prevented if the people in charge had just paid more attention. Case in point, according to United Press International, the exact same valve malfunction happened at Toledo Edison's Davis Besse power plant a full 18 months before the disaster at Three Mile Island. The difference? At Davis Besse, the plant operators quickly and effectively corrected the situation before a meltdown could occur. Three Mile Island, well ... didn't go so well. When this information became public, the owners of Three Mile Island attempted to sue the government for $4 billion, alleging that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission had withheld information regarding Davis Besse from them that could have prevented the meltdown. The claim was rejected, according to the New York Times, based on the argument that the Davis Besse operators had fixed their problem easily by following the correct procedures, whereas the Three Mile Island operators had bungled the job.

Regardless of who you blame, it's clear that everybody involved should have been paying more attention. Maybe things could have happened differently. But partly because the response to the problem at Three Mile Island and partly because of fears over the later Chernobyl disaster, the future of nuclear power in the United States really stalled out. This isn't too surprising, considering how humans can so easily screw up using ordinary bank ATMs, much less handle nuclear reactors capable of destroying the countryside for centuries.

Did the Three Mile Island incident cause animal mutations?

Many people have seen the heartbreaking photos of animals deformed by the Chernobyl meltdown, but the decidedly smaller radiation seepage at Three Mile Island has not, according to official reports, produced any similar results due to the fact that the radiation expelled into the atmosphere was minimal. That said, United Press International writes that following the incident, there were frequent reports of animal mutations and stillbirths. For example, over 20 farmers claimed that their animals and crops were experiencing health and growth issues. Hundreds of birds died in a two-hour span. One poodle was born with only one eye socket. An area man brought a supermarket fish into his basement and was shocked to find it glowing in the dark. Despite these scary stories, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission rejected the notion that the radiation had caused animal deformities, citing other causes.

The truth? To date, the subject hasn't been opened up again, and there are arguments on both sides. The slew of reports and rumors are the kind of thing that make you wonder, but there are lots of reports of alien abductions, too, so you can't believe everything you hear. For now it's probably best to chalk this one up as fishy but not proven.

What happened after Three Mile Island?

After a partial meltdown followed by one of the worst PR disasters in United States memory, Three Mile Island's reputation was tainted. The Pennsylvania power plant became synonymous with the inherent dangers of nuclear power, making Americans forever distrustful of it. Sure, Three Mile Island stories became less prevalent after Chernobyl exploded in 1986, but that's only because Chernobyl was so much worse, possibly rendering the area immediately surrounding it uninhabitable by humans for the next 20,000 years. Compared to that, anything looks better.

However, casual observers might be surprised to learn that the 1979 meltdown incident didn't end Three Mile Island, despite the many protests and arguments that continued throughout the decades. Actually, the power plant kept running for another 45 years, according to Popular Mechanics, until in 2019 it was struck down by the far more mundane triple threat of state government, natural gas companies, and the senior-advocacy group AARP. Yes, AARP felt really strongly about shutting it down. The new owners of the power plant, Exelon, repeatedly petitioned the Pennsylvania legislature for subsidies, but these efforts proved fruitless.

So yes, in the end, Three Mile Island only went under because it was losing money, not because of its association with one of the worst nuclear incident in U.S. history. Nonetheless, the power plant's name lives on as a point of debate in the great nuclear energy argument, and a fervent reminder of how easily things can go wrong.