Jackalope: The Truth Behind The World's Scariest Rabbit

If you've done a couple road trips across the United States, there's a strong chance you've spotted a jackalope or two. Not bouncing around, of course, but go to enough sketchy bars, mountain hotels, or rugged ski lodges, and you'll eventually see one of these cryptid creatures mounted on a wall.

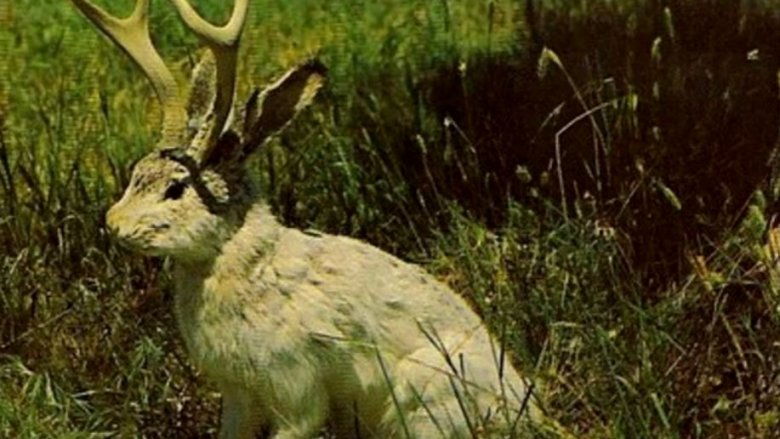

The jackalope, just like its hairy cousin Bigfoot, has become something of an American institution. Your local farmer might claim to have spotted them in his fields from time to time. Your classmate probably warned you that they're vicious if provoked. These deer-antlered bunnies are probably the most well-known animal from Wyoming ... which is a bit odd, considering that jackalopes aren't quite a real species. Or are they? Surprisingly enough, the answer is more complicated than you think, and while myths about these horned hoppers have existed for centuries, there is a scientific explanation for jackalopes. Let's dive in.

Jackalope legends date waaaay back

Believe it or not, the widespread belief in hares with horns goes back to the days before the USA was the USA. Nowadays, jackalope advocates will claim this as proof that the furry critters are real, but hey, people also used to watch the skies for dragons and clearly there's no giant reptile threatening New York City today.

Regardless, Wired points out that an ancient Persian geographic dictionary from the 1200s depicted a rabbit with a single, unicorn-esque spike on its head. Sure, maybe it isn't a perfect jackalope, but pretty similar. By the 1500s, more recognizable antlered bunnies popped up in various guidebooks, including Joris Hoefnagel's Animalia Qvadrvpedia et Reptilia (Terra) series, as well as a rather fearsome, fanged Bavarian "Wolpertinger" painting from 1509. Perhaps the true roots of today's jackalope, though, go back to Central America. According to People of the Peyote: Huichol Indian History, Religion, and Survival, one of the iconic heroes of ancient Huichol culture was Kauyumari, a deity sometimes called the Blue Deer, who was said to have first received his antlers from his friend, the rabbit. Long story short, the little rabbit thought his horns were too heavy to cross a river with, so he passed them down to the deer.

Are jackalopes real? People really thought so

Okay, so it's one thing to know that ancient people told "legends" about a jackalope creature, but people also tell legends about Marvel superheroes today, so that by itself doesn't prove that anyone actually believed in horned rabbits. But ... people really believed in horned rabbits and thought of them as real animals for a long time. They didn't call them jackalopes, though. The proper name was Lepus cornutus. It doesn't appear that there was even much debate on the matter of their existence, actually: In 1673, when the legendary British naturalist John Ray described seeing both "the head of a horned hare" and also "the horns of a hare" among an assortment of other, regular animal body part specimens, such as a dolphin's head and a tuft of rhinoceros skin, these rabbit horns are barely a footnote. In fact, the animal he believed to be a ridiculous myth wasn't the horned hare, but rather the hippopotamus. Admittedly, hippos are pretty weird.

That said, the Smithsonian claims that by the end of the 1700s, it seems that scientific belief in jackalopes died out. Why? Probably a lack of evidence, plus the refinement of scientific methods. Nonetheless, about two centuries later, all those horned rabbit stories would get a jolt to their little rabbit-y hearts.

An American icon is born

Horned bunnies are old school. The mythology surrounding the United States jackalope, though, is a fairly recent phenomenon, and unlike some other cryptids, the creature's origin story isn't quite so mysterious. According to the Los Angeles Times, it all began in the 1930s, when two Wyoming brothers named Douglas and Ralph Herrick went hunting. Having studied taxidermy as teenagers, the Herrick duo brought back a jackrabbit carcass to stuff. Upon returning home, in their rush to eat some dinner, they casually dumped the rabbit body into their taxidermy shop ... where it landed, coincidentally enough, right next to a set of deer antlers.

Now, if this were a cartoon, the camera would have zoomed in on the antlers, cut to Douglas Herrick's face, and then shown a lightbulb popping up over his head. It's said that Douglas immediately announced that they should mount the antlers upon the rabbit's skull, and while it's impossible to know what Ralph thought of this wacky suggestion — "has my bro gone crazy?" would have been a suitable response — he went along with the idea.

Some salt, stuffing, and antler attachments later, the first jackalope mount was born. Once the word got out, the Herrick brothers had a new business plan, and selling jackalope souvenirs would become their eternal legacy.

Tales of the jackalope

Hey, you know what happened once people started seeing the heads of these freaky rabbit creatures mounted in bars across the United States? Yep, you guessed it: They told tall tales, and those tales sprouted even taller tales. None of these stories existed before the Herrick brothers pulled their little stunt, mind you, but they caught on quickly. For instance, the Museum of Hoaxes tells how cowboys in the Wild West supposedly gathered around the fire at night, sang old songs, and often heard the jackalopes singing back to them in astonishingly human voices. Oh yeah. Snake oil salesmen claimed that the milk of a jackalope was a potent aphrodisiac — horny rabbit, get it? — while other hoaxsters said that the best way to catch one of these beasties was to use whiskey as bait because the rabbits loved getting drunk on it. Naturally, salesmen often told their customers to avoid the so-called "warrior rabbit" in the wild, since jackalopes were very aggressive when provoked.

Whiskey, frankly, was probably the key ingredient in a lot of these goofy fables. Nonetheless, it was only a matter of time before jackalope "sightings" started popping up to go along with the stories. According to American Myths, Legends, and Tall Tales, jackalope lore and sightings are particularly concentrated in Douglas, Wyoming, the place where the Herrick brothers first launched their enterprise.

The creator of the jackalope lost interest

As everybody in the town of Douglas, Wyoming, continued to go wild with jackalope fever, one man greeted the extended craze with a yawn: Douglas Herrick himself. After creating the jackalope and mounting the first 1,000 of them, the Los Angeles Times reports that he called it quits. Admittedly, taxidermy isn't easy, and mounting a thousand of any kind of wall trophy probably gets old. His brother, Ralph, though, was as charged up as the Energizer Bunny and kept the mounts coming. According to the New York Times, Ralph churned out hundreds upon hundreds of the things, eventually passing down the trade to his son, Jim, who continued to deliver jackalopes as recently as 2003. Talk about an unusual family business.

As the decades went on, other taxidermists got into the swing of things, such as Frank English of South Dakota. English is now considered one of the world's foremost jackalope makers, and the Billings Gazette writes that he has made a full-time job of this shebang since the '80s. He says one of his favorite stories came from an airport customs snafu in the U.K., where a jackalope head found in an American woman's luggage was confiscated because it was presumed to belong to a protected species.

Just to be clear, none of these jackalope mounts ever belonged to real jackalopes. However, scientific research has discovered a creepily real version of the jackalope in the wild.

The disturbing truth about the real jackalope disease

Are jackalopes real? In a manner of speaking ... yes, actually.

Wait, hold onto your horns. Bizarrely enough, there truly are rabbits out there who have hornlike growths sprouting from their heads, according to Wired, and it's quite possible that these unusual bunnies inspired some of the myths. The sad news, though, is that these growths aren't antlers, true horns, or anything nice or fun or fantastical like that: They're hard, keratinized tumors, which are the result of the cancer-causing Shope papillomavirus. Sound familiar? That's because when this virus infects humans, it's called HPV. In humans, HPV causes cancerous tumors to appear in the cervix, but when it hits rabbits, the tumors manifest as hard growths from the skull. The disease eventually kills them, so these horns are not harmless appendages but a terrible progression of their illness. By the way, they don't necessarily grow these things on the top of the head, either. Often, the growths block their mouths, causing the afflicted rabbits to starve to death.

The reality of horned tumors is definitely a bummer, but it does a lot to explaining some of the jackalope myths, as well as the centuries of pre-jackalope myths.

How long has the world known about the jackalope disease?

So, here's the funny thing about Lepus cornutus: This whole jackalope disease isn't some wild new revelation to the scientific community, even though most laypeople haven't heard of it. As Gizmodo explains, the scientist who lit the fuse was Richard Shope of Rockefeller University. In the 1930s, Shope heard about jackalopes on a hunting trip. In response, he didn't do what the average person would — that is, take a swig of whiskey and tell an even taller tale — but rather, took the scientific approach of having his friend catch a real horned rabbit for testing purposes. Yes, it was that easy. Shope then acquired a tissue sample of the horns, ground them up, filtered out everything but the viruses, and rubbed the filtered solution onto the heads of healthy bunnies. Oh. Science.

Guess what? Horns grew, demonstrating that these protrusions were, as Shope had hypothesized, tumors created by a virus. Yikes. Shope's colleague, Francis Rous, then took it a step further. Using rabbit tissues given to him by Shope, Rous spent the next few decades injecting viruses deep into rabbits, which caused them to develop aggressive cancers. This work, gruesome as it might be, was a landmark achievement in affirmatively linking viruses and cancer, and in 1966, Rous was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for it.

Douglas, Wyoming, is the official home of the jackalope

So why are jackalopes still a rural legend across the United States? If you're a small-town public official who wants to bring tourists to your small town that nobody's ever heard of, and your local taxidermist creates a fictitious beast whose fearsome reputation goes viral across the country, what's your next move? Well, you ride those coattails, of course. That's exactly what Douglas, Wyoming, did and continues to do today.

The fact that anybody still believes in jackalopes in the present day is a testament to how Douglas has spent almost a century spreading one of the USA's most lucrative hoaxes, mostly by marketing the fabled beast like crazy. The self-proclaimed jackalope capital of the world, according to Atlas Obscura, Douglas boasts the world's largest jackalope sculptures, including the big guy in front of the Douglas Railroad Interpretive Center, and a 13-foot-tall jackalope silhouette perched up on a hill overlooking the town. The Douglas Chamber of Commerce also offers tourists official jackalope hunting licenses, though the specified hunting season lasts a mere two hours a year. You'd have to be the fastest gun in the West to shoot a jackalope in season.

Of course, while Douglas is jackalope central, the rest of Wyoming has gotten in on the joke, too. Governor Ed Herschler officially designated Wyoming as the jackalope's stomping grounds in 1985, according to the New York Times, and the very name jackalope — which, if you hadn't noticed, is a very on-the-nose portmanteau of jackrabbit and antelope — was trademarked by the state of Wyoming in 1965.

The original jackalope head was stolen

Popular jackalope lore says that the first person to spot the fabled beast — and live to tell about it, of course — was a "trapper" by the name of Roy Ball in 1829.

Like many tall tales, there's a seed of truth here, but it grows into an awfully obscured tree: Roy Ball was a real person, for sure, but the New York Times reports that his actual role in the great jackalope story was that he was the man who purchased the very first antlered rabbit mount from the Herrick brothers in 1934. Ball then proudly displayed it on the wall of his hotel, the LaBonte. How much did he pay for this decoration? Ten bucks, according to the Los Angeles Times. Anyhow, Ball's many guests probably got quite a kick out of the display, but one unknown party was rather maliciously fascinated, so much so, in fact, that the original jackalope head was reported stolen in September 1977.

Sadly, it seems that the historic stolen head has never been recovered. Needless to say, that poor thing would be worth a lot more than $10 today, and the Hotel LaBonte, which is still in business, would probably love to have it back.

The (fake) jackalope documentary

The cuddly-looking jackalope doesn't tend to elicit the same chills as its creepy cryptid cousin, the chupacabra, so it probably won't inspire too many low-budget B-horror flicks. That said, if you feel like you once might have seen a real documentary about real jackalopes, well, the chances are that you fell for the goofy 2006 mockumentary Stag Bunny, according to the Casper Star Tribune. Made by a bunch of recent Wyoming film school grads, Stag Bunny humorously presents the jackalope as a real animal, with a slim script and a lot of ad-libbing. Of course, the best part of the film is certainly the interviews the crew did with real Douglas locals, all of whom were in on the joke. These included Mike James, the owner of a sporting goods store who allegedly possesses the only known jackalope living in captivity, and a real paleontologist who was willing to make a bogus description of the jackalope's fossil record on camera.

While Stag Bunny is a special film, being that it was made by Wyoming locals for fellow Wyoming locals, it's not the only jackalope media out there. Plenty of other people have done fake jackalope sightings, fake footage, and fake interviews, and so the legend lives hoppily on.

The weirdly contentious battle for recognition of the jackalope

Most people agree that jackalopes are silly. In Wyoming, though, the jackalope is quite serious business, as these furry creatures are a definitive symbol of the equality state, as well as a great marketing tool. Despite their popularity, the Casper Star Tribune reports that the Wyoming state legislature has spent over a decade trying to ratify the jackalope as the state's "official mythical critter," with little success.

You'd think that giving the jackalope such a tag would be easy, but c'mon, this is politics. So, instead, it's been a long, bizarre battle, with the initiative frequently moving forward, getting killed, and then being revived. The original advocate for jackalope recognition was Rep. Dave Edwards, who sponsored the jackalope bill in 2005 and even went so far as to bring ten mounted jackalopes with him to the House floor. Of course, the bill failed and he was crushed. In 2013, after Edwards died of Alzheimer's complications, his former colleagues — Rep. Dan Zwonitzer in particular — put forth a new bill on the subject, called the David Richard Edwards Memorial Act. That bill passed the Wyoming House, but died in the state's senate.

Two years later, Zwonitzer reintroduced the bill, and vowed to the press that he'd never let it go, telling everyone that he would "keep bringing it back until it passes." So far, it seems that he's had no luck. That said, a jackalope named YoLo did become the mascot for the Wyoming Lottery (WyoLotto), so that might be one small step toward acceptance.