The Disastrous History Of Legos

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Every kid loves Lego, unless you were one of those kids who lacked the sort of creativity it takes to build anything better than a large, straight-sided, multi-colored tower. Not that we know anyone like that or anything. Anyway, every parent loves Lego, too, especially when you're fumbling your way to the bathroom in the middle of the night and your heel lands right on top of a 1x4.

In those dark hours, you may stop and curse the name Lego under your breath, but not too loudly because then the kids will wake up and it really will be a nightmare. But think about it—if enough parents curse the name Lego at the same time, then perhaps the Lego company will fall under a spell of bad luck and do something stupid like start releasing sets of gladiator figures with interchangeable arms and then suffer the financial consequences of their poor choice. Who knows, maybe parents have been cursing the Lego company all along, and that explains the bizarre series of misfortunes that have been plaguing them since 1924. What bizarre misfortunes? These ones. So read on, and if you truly love Lego, try to bite your tongue the next time you step on a 1x4.

First, the Lego workshop burned down

Lego is an old company, in fact, it dates all the way back to 1916 when a young Danish carpenter named Ole Kirk Kristiansen bought a carpentry shop for 10,000 Danish Krone. According to Lego, Kristiansen married his wife around the same time, and the couple went on to have four children.

At first, Kristiansen just continued making the sorts of products the shop was already making, like cabinets, doors, chests of drawers, and coffins, but eventually, he expanded into building houses and agricultural buildings. So things were going pretty well for the family until 1924, when Kristiansen and his wife decided to take a nap while the kids played in the workshop with the glue heater, a box of matches, and a pile of wood shavings. You can probably guess what happened next. "My first achievement was to burn the workshop and house down," one of the boys would later say.

Hey Ole, every parent knows you should never leave your kids alone in a workshop without anything to do. Instead, you should leave them alone in a padded room with a box of Lego. Try that next time.

Things were looking up for Lego ... and then they weren't

Kristiansen was not a man to be brought down by a little thing like the loss of his entire home and livelihood, so he built himself a new workshop and a new house. If you're Lego-obsessed, you can even go visit the house because it's still standing on Main Street in Billund, Denmark.

At some point, Kristiansen started making toys out of scrap wood, probably around the time he realized he should be giving his kids something to play with besides matches, glue heaters, and wood shavings. Pretty soon, things were looking up again, but then in 1929 Wall Street crashed, and by 1930 the UK and the USA had both placed restrictions on imports, including Danish farming imports. According to Lego, prices of things like butter and pork started to crash, and some of Kristiansen's biggest customers could no longer afford to commission carpentry work. Kristensen had to let his employees go, and by 1931 he had no journeymen left. And then, because things weren't already bad enough, in 1932 Kristiansen's wife died from complications of phlebitis, leaving him alone to care for four children between the ages of 6 and 15.

But the guy was seriously resilient

So at that point, Kristiansen was at an even lower place than he was in 1924 when he lost his home and workshop. But he wasn't the sort of guy who would just throw up his hands, sit down on the living room sofa with a bag of Cheetos and binge-watch all six seasons of Lost because why bother? Nope. And not just because Cheetos and Lost didn't exist yet, either.

According to Famous Inventors, Kristiansen started to make small, affordable products like ironing boards and stools, things people would still buy in the uncertain economy. That was around the time he also started to make toys for sale—in fact, he joined his father and the two made high-quality toy vehicles from birch wood and quickly earned a reputation as quality craftsmen. As time went on, the company began to focus more on toys and less on other products, and Kristiansen eventually felt the need to select a new name for his company. "Lego" was a shortened version of the Danish words Leg and Godt, which means "play well."

By the mid-1930s, Lego was producing 42 different product ranges and things were looking up again. But you know it couldn't last, right?

Then, the Lego workshop burned down again

On the night of March 20, 1942, another fire swept through the Lego factory. Kristiansen's home—which was adjacent to the factory—was miraculously spared, but the entire wood products business was destroyed, and the disaster was enough to finally rob Kristiansen of his will to continue. According to Lego, "Only his sense of responsibility for his sons and employees persuad[ed] him to rebuild the factory."

Kristiansen eventually secured a loan and was able to rebuild on the same site, and the new factory ended up being an improvement on the old one—it was more modern and designed specifically for producing toys. When it was finally completed in 1943, productivity went up. But on the flip side, Kristiansen lost all of his models and patterns and had to recreate everything from scratch.

When you've got a clean slate, though, you've got opportunity for change. After the fire, Kristiansen decided to add self-locking blocks to his product line, and 1947 the company bought its first plastic injection molding machine. For a while, the company continued to produce both wood and plastic toys, before finally abandoning wood and focusing solely on plastic.

The death of Lego's founder

Ole Kirk Kristiansen died in 1958, the same year the company came up with the groundbreaking design for the Lego blocks we know today. So even though all of his hard work, innovation, and personal loss led to one of the world's most beloved toys, Kristiansen never really got to see what his company would eventually become. That same year, Lego expanded its factory, opened a new molding shop, and was running 40 injection molding machines with plans to obtain an additional 15.

According to the Independent, the 1958 design of the Lego bricks overcame the problems of the older designs—the earlier bricks just didn't stay together that well. Before 1958, kids had to use adhesives and special connectors to hold their creations together, which means they couldn't be easily disassembled and rearranged. The new design featured hollow vertical tubes on the underside of each brick, which could easily lock together with the studs on the top. This was a big moment for Lego, and all the Lego bricks sold today can be interlocked with any of the bricks produced since that innovative design first landed on store shelves.

What is the deal with all these fires?

It's probably a good thing Ole Kristiansen was already gone in 1960, because the news of yet another disastrous fire might have destroyed the poor man. According to Lego, fire struck the company again in 1960, wiping out an entire warehouse and all of the company's inventory of wooden toys. That was the incentive the company needed to finally discontinue its line of wooden toys.

Loads of new designs followed. In the 1960s, the company introduced a round brick with a rubber tire, and it now produces roughly 300 million of them a year (making it officially the world's largest tire manufacturer.) It came out with a line of larger, chunkier blocks for preschoolers and it even launched its own theme park—Legoland in Billund has been open since 1968. The little people (minifigs) came out in the 1970s, followed by medieval castles, spaceships, and astronauts. Lego became Lego as we know it, and it was kind of like the multi-primary-colored phoenix of plastic, rising out of the ashes of all those factory and warehouse fires.

But then, the Lego patent expired

There comes a time in every innovator's multi-generational uber-successful business when the patent expires. For a company like Lego, which basically put all of its bricks in the same cardboard packaging, an expiring patent can be the kiss of death.

According to the Washington Post, in the late 1980s, Lego's innovative design became fair game for just about everyone with a plastic injection mold and no actual creativity of their own. Other companies started to copy the Lego design and Lego even tried to fight back, but alas, it was no match for the power of the limitations of global patent law. Fortunately, the company had high quality and brand recognition going for it, and many customers remained loyal. By the early part of the next decade, Lego's sales were growing by double-digits, and they controlled around 80 percent of the building toy marketplace. By the 1990s, the company had the licensing to produce its first line of Lego Star Wars toys, which quickly became the company's most popular line, bringing in a full 15 percent of the company's revenue. Nope, the expiration of the company's patent didn't seem to hurt them at all.

And then, a series of dumb moves

Ultimately, companies are only as good as the decisions of their top people, and in the mid-1990s to early 2000s, Lego's top people made some really dumb decisions. According to Business Insider, in 1996 the company released a line of cool micro-motor and fiber-optic kits, but no one at Lego was dialed into the minor details like, you know, the cost of all those high-tech parts. As it turned out, it cost more for Lego to obtain the parts for these sets than the sets were actually selling for, so they were taking a loss and they didn't even know it.

So who was the genius that came up with this particular product idea? Well, the top people at Lego had evidently decided the company needed to modernize, and in order to do that it needed to get rid of all the oldies. So it "retired" a lot of the designers who'd helped grow the company between the 1970s and the 1990s, and it replaced them with a bunch of hotshot young graduates from the top European design colleges. They were talented people, sure, but they weren't toy designers, and together they helped balloon the Lego product line from a sustainable 6,000 different parts to more than 12,000. That meant the company needed to increase its infrastructure even though it wasn't seeing any real increase in sales.

And then they released a bunch of really stupid Lego sets

In the late 90s, Lego responded to some of its competitors with designs that veered from its traditional interlocking bricks and into the territory of other, already-successful construction toy companies. According to Business Insider, between 1998 and 1999 Lego released its Znap line of products, which was basically a rip-off of the popular K'Nex line of toys. C'mon, Lego. Stay in your own lane. Anyway, Znap was actually the inferior product, and consumers saw no reason to leave K'Nex.

Znap was released around the same time as several other unsuccessful lines, including Primo, which was basically Lego for babies only without any compatibility with standard Lego bricks, and Scala, which was Lego's answer to Barbie. Scala sets also were incompatible with Lego's other products, though they did include flower-shaped brick studs so they'd be kind of sort of Lego-ish.

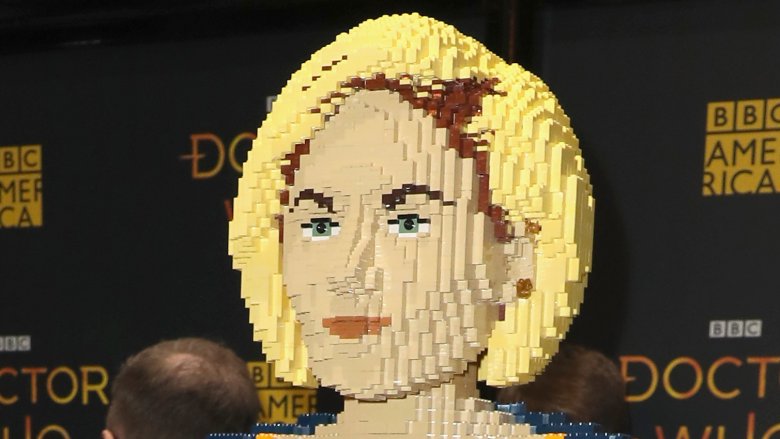

By far the worst set that came out during this time, though, was "Galidor," which was a set of action figures that bore no resemblance to any other Lego product unless you count the fact some of the parts were interchangeable. But the interchangeable parts were like the stupidest thing ever—you could swap character arms, for example, because everyone knows superheroes occasionally need access to other people's arms. Lame.

Bankruptcy looms

By the early 2000s, Lego was near bankruptcy. According to Strategy Business, they still looked pretty good to the outside world—in 2000 the British Association of Toy Retailers and Fortune magazine named Lego "the toy of the century," and in 2004 sales topped $1.35 billion. But between 1998 and 2004 Lego was actually losing money, and sales dropped a whopping 30 percent in 2003 and another 10 percent in 2004. Profit margins were in the red at -30 percent. According to some internal estimates, Lego was losing $337,000 in value every single day.

So was it all those seriously lame product lines? Partially. But some experts think Lego was also clinging too much to the things that worked for it in the old days—it was still spending a lot of time on brand building, even though it was one of the most recognizable brands in the world. And it had almost completely failed to recognize big box stores were replacing the smaller retailers that had formed its customer base for decades—so while other toy companies were adapting to the demands of those major chains, Lego was dragging its feet.

Meanwhile, back in court

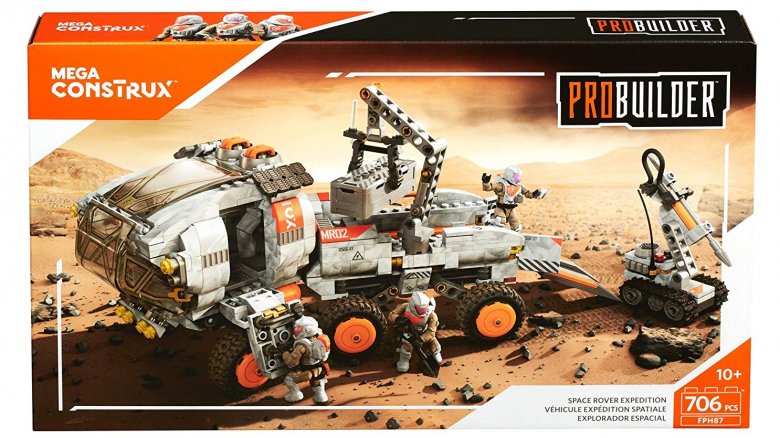

Lego's biggest copycat is Mega Bloks, which so blatantly stole the Lego design that its bricks are even compatible with Lego bricks. And if you don't know anything about patents, it seems crazy that Mega Bloks could get away with such a thing. But Lego no longer has an exclusive claim to that tube and stud design, and no amount of lawsuiting could evidently change any of that.

In 2005, Lego lost its last-ditch effort to tell Mega Bloks to knock it off. According to CBC Canada, the Canadian high court ruled unanimously that Montreal-based Mega Bloks could continue to use Lego's original stud design. Because it no longer owns the patent, Lego argued that Mega Bloks' use of the design amounted to trademark infringement. The courts disagreed, though, saying that the studs were "purely functional" and could therefore not be used as the basis of a trademark. "Trademark law should not be used to perpetuate monopoly rights enjoyed under now-expired patents," the court said. And so ended Lego's claim to its own brick design.

Then Lego made a move that pissed off consumers

In 2012, Lego released the "Friends" line of products, which was basically a less lame but equally gender-stereotypical version of Scala. In the 2010s, though, consumers were starting to dislike products that pigeonholed kids into gender-specific play. Lego has always been seen as a gender-neutral toy, and a lot of parents were upset that Lego seemed to be trying to divide its products into for-boys and for-girls categories.

According to the Atlantic, Lego's own research revealed that around 90 percent of the Lego sets sold around the world were being purchased for boys. So there was a huge, untapped market for Lego sets aimed exclusively at girls, but the way Lego decided to confront the challenge just showed how out of touch it was about the modern market for girls' toys.

In 2012, Lego released said Friends line, which mostly included toys that showed girls doing stereotypical things, like going to the hair salon and the mall. Lego was almost immediately met with backlash—consumers and critics accused the company of "dumbing down" Lego because of a misguided belief that girls as less capable builders than boys. The line even got a TOADY award, which stands for "Toys Oppressive and Destructive to Young Children." Ouch.

Then Lego pissed off Greenpeace

Granted, this incident and the Lego Friends one happened after the company finally started to recover, but both were concerning because they showed that the company hasn't totally adapted to the trajectory of consumer opinion. According to the Guardian, in 2014—while Shell Oil was making plans to drill for oil beneath melting Arctic ice—Lego made the inexplicable decision to release a line of Shell-branded vehicle kits.

The move upset, among other people, Greenpeace, which collected 750,000 signatures urging the toymaker to abandon its deal with Shell. "Shell is a company whose interests lie in direct contrast to children's [interests]," wrote Sue Palmer, author of the book Toxic Childhood, "embroiled on the wrong side of the struggle to limit global warming and prevent its worst impacts."

The Greenpeace campaign and resulting public outrage were enough—in October of 2014, Lego announced that it would not be renewing its partnership with Shell. Earth: 1. Big oil and gas: A bazillion or so. But still, progress.

How Lego fixed everything

A company that can bounce back from three devastating fires has the kind of resilience that can save it from almost anything, and today Lego is as strong as it's ever been. In 2014 the Lego Movie made $69 million in its opening weekend, so it's come a long way since the early 2000s.

According to Business Insider, when Jorgen Vig Knudstorp became CEO in 2004, he immediately reined in expenses and hired some fresh new designers, many of whom were lifelong Lego fans, people who were clearly best-equipped to come up with the fresh designs and innovations that the company needed. Knudstorp cut the ballooning inventory of parts in two, linked design and manufacturing costs (at last!), axed the computer games business, and streamlined the business in general. But the biggest thing Lego has done to improve its bottom line is return to the sorts of products we all remember from our childhood—those interchangeable bricks that still have the look and feel of the original. That's what Lego has always done best, and in all likelihood, it's what will sustain the company in the future.