The Most Devastating Weapons From The Medieval Period

Medieval people have got nothing on modern people. We have warplanes, submarines, and nukes; they had longswords, crossbows, and pitchforks. So how could any medieval weapon be "devastating," really? Comparatively speaking anyway.

Well here's the thing. We have the Geneva Conventions and the Hague Conventions, which basically say, "Hey, while we're killing each other we agree to maybe not kill each other so horribly and, you know, to not torture and abuse war prisoners and civilians." Medieval people had no such rules. Pretty much everything was fair game, including pillaging and murdering innocent people and killing each other in the most gruesome ways possible. So when we talk about devastating modern weapons, we tend to talk about those weapons that can wipe out a very large number of people very quickly. But when we talk about devastating medieval weapons, well, those are the ones that can take down a very large number of people very quickly, but they're also the ones that cause horrible destruction, and/or kill people in gruesome and awful ways. So stick around, because there's much horror and heartbreak ahead.

Before there were guns, there was the English longbow

It doesn't seem like much: a piece of yew four to six feet in length with a string made from linen or hemp. But what made the English longbow so devastating was its range and accuracy—some scholars have estimated a well-trained archer could hit his target from up to 270 yards away, although 75 to 80 yards was probably a more realistic average. The usual tactic didn't depend on aim, though. Instead, a row of archers would release a volley of arrows into a line of enemy troops, thus wiping out most of them before they got close enough for hand-to-hand combat.

According to Historic UK, the longbow made its first major appearance during the Anglo-Norman invasion of Wales. It played an important role in other key battles, too, like the Battle of Crecy in 1346 and the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, but it's most remembered as the weapon that won the Battle of Agincourt. Here's how that battle went down: Henry V was outnumbered more than four to one, but the French were bogged down by muddy ground, and the English had archers. By some estimates, the archers were able to take out between 6,000 and 10,000 French soldiers in roughly a half-hour, while their own losses amounted to only a few hundred.

The longbow remained the dominant long-range weapon on the European battlefield until it was replaced by the musket in the mid to late 17th century.

Little pigs, little pigs ...

One type of warfare you don't hear as much about anymore is the siege—it happened a lot in medieval Europe and though it does still happen today (the Battle of Aleppo is one such example), it's a very different sort of enterprise than the one we're used to seeing in popular entertainment. Back in the Middle Ages, if you wanted to control someone's land you first had to take his castle, and the best way to take a castle was to besiege it. This was true for a long time, long enough for a sort of arms race to grow up around this particular type of warfare.

According to Lords and Ladies, the battering ram was a weapon made from the trunk of a large tree, which was used to bash a hole in or knock down a castle gate or even the wall itself. It took up to 100 men to actually make the thing work, and each one had to have skill, excellent coordination, and giant cojones.

If you were operating the battering ram you were a pretty obvious target for the people who were defending the city, so battering ram operators had to do their work inside a "battering ram penthouse," which was basically just a shed made out of wood and braced with iron plates. Hopefully, that was enough protect everyone, but it's probably a safe bet that "battering ram operator" wasn't the most coveted job in the army.

My crossbow is bigger than your crossbow

The crossbow is a seriously lethal weapon even today—it's quiet and accurate and has killed an awful lot of zombies over the past decade or so. So what in the medieval world could possibly be more lethal than a crossbow? How about a really, really big crossbow?

The ballista—yet another siege weapon—was precisely that: A huge crossbow designed to fire large projectiles over the walls of a besieged castle. The ballista is actually a fairly old design—according to Ancient Fortresses, it was probably invented by the ancient Greeks and modified by the Romans before becoming a favorite siege weapon for medieval Europeans. Attackers used the ballista to fire enormous wooden arrows with iron tips, and you really would not want to be the guy in the path of that thing while walking around the castle grounds selling meat pies or whatever it was you were doing. Also, a ballista could release like 1,000 missiles a day, which basically means your pie business isn't going anywhere for a while. Hmm, maybe a job outside the castle grounds would be a safer plan.

Out of rocks? There's plenty of poop.

Today, they're mostly just used for flinging pumpkins across fields in October, but once upon a time the trebuchet was a very serious, potentially lethal siege weapon. And unlike the ballista, the trebuchet gave attackers some real versatility. You could use a trebuchet to fire just about anything over the walls of a castle, and sometimes after a very long siege just about anything was pretty much all you had left. Fortunately, it doesn't matter if you're flinging rocks or tree stumps or animal dung or a bag of groceries over the castle walls, what matters is it that the thing you're flinging ends up on someone's head.

Like the ballista, the trebuchet's origins are older than the Middle Ages—according to Medieval Life and Times, it was probably invented in China around 300 BC, but it didn't arrive in Europe until 500 AD or so, and for a while it was only the French who were using it. It was passed on to the English in 1216 after the French used it during the Siege of Dover and the English went, "Hmm, what is this terrifying machine that's laying waste to our castle? We've got to get us one of those." In fact after the Siege of Dover, Edward I ordered his chief engineer to build a bigger, even more terrifying trebuchet named "The Warwolf," which is still thought to have been the most powerful war machine of its kind.

Rest in pieces

Biological warfare is one of the those things that we don't do anymore, mostly because it's just seriously sucky and not very nice in general. The real problem with biological warfare, after all, is that it isn't just the soldiers you're killing, it's all the civilians, including children, too. But it wasn't that long ago biological warfare was just another day in the war room. Even Americans were guilty of the practice—everyone has heard stories of how whole Native American villages were wiped out by blankets contaminated by smallpox.

But biological warfare actually goes back to even before that disgusting chapter in US history. During the Middle Ages, attackers would sometimes use dead bodies as a form of biological warfare against a besieged castle. Even in those days, when humans thought disease was caused by various disgusting forms of bodily fluid that don't exist, people knew you could get sick from handling or being close to the remains of a person who died from a communicable disease. So attackers would sometimes launch rotting corpses over the castle walls. Yuck. Similarly, Bartleby says they could use rotting corpses to contaminate the city's water supply—they'd just have to drag them upstream and leave them in the water. Never mind that the water would carry on from there to other not-besieged cities and villages, because hey, it's only peasants, right? That's the cost of doing business.

French fried French

Hollywood loves to recreate the horrors of medieval war, and one of their favorite horrors is the boiling oil attack. If you've ever splattered hot oil on yourself while cooking french fries, you got a very small sample of what it was like to be on the receiving end of this crude weapon—imagine that but all over your body. Also, there's no cold running water and your doctor will mostly just cut you open and let all your blood drain into a pot, so the experience will be followed by either immediate death or infection and then death, the former of which is actually starting to sound pretty good.

If you believe the movies, boiling oil was a common defensive tactic employed by a castle's defenders against soldiers who were trying to breach the walls. But alas, there's not a lot of evidence it was really used that often. According to History Extra, there are only a few records of boiling oil being used during certain castle sieges, and that's probably because oil was expensive and not that easy to come by. So it made more sense for defenders to use substances that were easier to obtain, like boiling corpse-contaminated water, or quicklime, or hot sand, and if you're thinking to yourself that hot sand sounds pretty tame compared to hot oil, you've clearly not ever had to walk barefoot across a beach on a 100-degree afternoon.

Heck with it let's just blow each other up

The cannon arrived on the scene in the 13th century, but gunpowder wasn't a new invention—it dates all the way back to roughly 850 AD or so, when Chinese alchemists sort of blundered into the formula while trying to create an elixir for eternal life. By the mid-1300s gunpowder spread to Europe, and the French and the British both had primitive cannons in their arsenal. But according to the Ancient History Encyclopedia, those early cannons were not super-effective for a couple of reasons—first, they were really inaccurate, and second, they had a tendency to kill the people who were using them in addition to the people they were being used against.

Around the same time they started using cannons on the battlefield, Europeans also started mounting cannons on ships, which was all well and good until the enemy also started mounting cannons on their ships, and suddenly everyone had to worry that some pirate or another was going to blow a giant hole in your ship's hull and send you to the bottom of the sea, so great idea everyone.

By the 15th century, cannon design had improved and the weapons were becoming more important to an army than knights and bowman. And not long after that, cannons became a lot smaller, and smaller still until you could hold them in your hand, and that's how modern warfare was born. Hooray?

It's a little warm for sailing, isn't it?

Fire is a terrifying enemy. It's one of the most devastating forces on Earth, and it's one of the most difficult to defend against. So it's really not surprising that ancient people learned how to use fire as a weapon pretty early on in history. You've probably heard of Greek fire—the defenders of Constantinople used it against a fleet of invading ships, and the invading ships ended up being pretty sorry they'd ever heard of Constantinople.

Sadly (or happily) the formula for Greek fire has been lost, so there are no samples of it in secret labs, and no mad scientist will ever steal it and then threaten to unleash it on the world in exchange for one billion dollars. Whew. But even without Greek fire humans still managed to set fire to the sea. According to War History Online, people were using "fire ships" as early the Peloponnesian War in 431 BC—these were ships that were deliberately set on fire and then set adrift into the midst of an enemy fleet. Fire ships were used throughout the medieval period, though they didn't start to become sophisticated until the Renaissance. That was when someone finally got the idea to stuff a huge ship full of gunpowder so that it would explode, preferably in the middle of the fleet, thereby sending as many ships to the bottom as possible. These particular fireships were called "hellburners," for fairly obvious reasons.

Watch your step

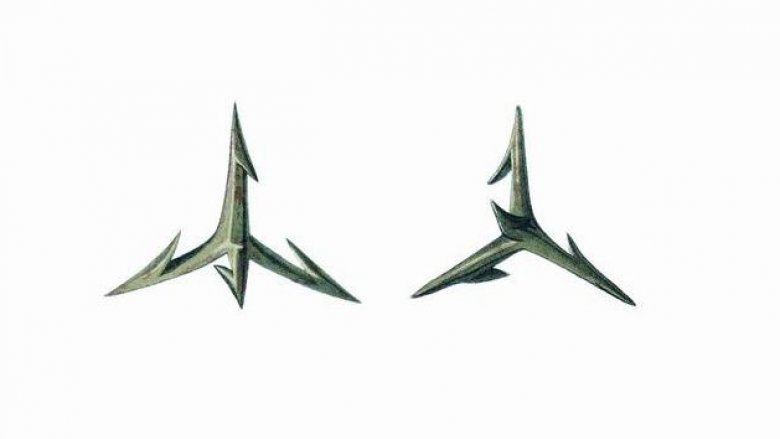

So how do you stop a cavalry charge? Well, you can do it with your longbowmen, or you can fire a cannon into enemy lines, or you can close your eyes and wish real hard. But if you don't have a cannon or longbowmen or the power of wishes, there are other ingenious things you can do and one of them is to scatter caltrops over the field between you and your enemy.

The caltrop was medieval Europe's own landmine—it didn't explode when someone stepped on it, but it caused an awful lot of damage, enough to cripple your attackers before they got within range. You can think of it sort of like those spikes in a parking lot that threaten "severe tire damage" if you dare to put your car in reverse, only the caltrop delivered severe foot damage.

According to Lords and Ladies, the caltrop was a four-pointed spike that could basically be tossed or scattered onto the ground without a lot of care, because when three of the spikes were touching the ground the fourth one would be sticking straight up, ready to slice up feet or hooves. Effective, but not unlike landmines, it seems like leftover caltrops would pose a bit of a hazard for those riding into town post-battle, or anyone who's wandering around at night in search of the outhouse.

My kingdom for a horse

Once the great liberators of the human race, today horses mostly get to carry city folks around on novelty trail rides or if they're very lucky, prance around on dressage courses. But once upon a time, horses changed everything for people. They made it possible for us to travel long distances. They made agriculture more efficient. And they made it possible for small armies to kick the butts of larger armies.

There is a reason why Shakespeare's Richard III was willing to trade his entire kingdom for a horse—according to the American Museum of Natural History, a knight mounted on a horse had a big advantage over a foot soldier. He had speed and power, which meant he was hard to stop and even harder to catch. The 15th-century Spanish knight Guiterre Diaz de Games summed it up nicely when he said, "There is no other beast which so befits a knight as a good horse ... A brave man mounted on a good horse may do more in an hour of fighting than ten or maybe a hundred could have done afoot."

Hwacha backs everyone

Medieval Europeans didn't have the monopoly on terrifying siege weapons—they were used in Asia, too, and because Asia also had gunpowder they were able to come up with some truly novel ways to launch weapons at opposing forces. In Korea, they had the hwachas, which was essentially an early rocket launcher. The hwachas is best known for its use during the Imjin War in the late 16th century, when it helped prevent the Japanese conquest of the Korean peninsula, but by then it had already been in use for at least two centuries.

According to Ancient Origins, hwacha loosely translates as "fire chariot," and if you saw this thing in action you'd know why. At first, it kind of looks like a weird cribbage board—it's just a flat piece of wood with a bunch of holes in it mounted on a two wheeled cart. But inside each hole was an arrow attached to a tube of gunpowder. So when the operator lit the thing, up to 100 arrows would go shooting up into the air. And that was just early versions—later versions could fire twice that many arrows. So really, a hwacha was as good as 200 longbowmen. So much for the whole conquering the world thing, England.

Don't mind this giant mobile tower thingy

During the Middle Ages, sieges could go on forever. The castle's occupants generally avoided surrender, and the attackers generally avoided giving up, so the result could be a long, drawn-out stalemate that ended when one group or the other finally ran out of food. But no one really wanted a siege to go on that long, so innovators were forever coming up with ways to get soldiers over castle walls. Clearly, this could not be done via trebuchet (though that might have been kind of fun, at least on the upswing). So attackers sometimes used a weapon called a siege tower, which was basically just a solider delivery system.

According to Medieval Chronicles, the siege tower was used by the Greeks, the Romans, and the ancient Chinese, so it was really more of a technology adoption than a European invention. The siege tower was a mobile building, built the same height as the castle walls with its own walls and a roof. The tower would be moved to the castle, and then the soldiers inside of it would, in theory, place a sort of bridge between the tower and the top of the wall and then just run across the bridge. Easy peasy. Except of course it wasn't, because everyone inside the castle knew what that thing was for and pretty much everyone would try to destroy it and its occupants before they had a chance to actually complete their mission.