Cold Cases Solved With Genetic Genealogy

Starting in 1869, various scientists worked out just what deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was and how it did its thing, and humanity gained a brand new insight into how the whole shebang of life and heredity works. This twisted double helix of self-replicating, trait-bestowing, life-defining science goop is the blueprint for ... well ... every inherited trait we possess. Born with a weird thumb that bends back too far? Thank your DNA for it. Got the same knobbly knees your grandma was cursed with? Yep. DNA is your culprit there also.

Today, a sample of saliva is all it takes for companies like GEDmatch to paint a detailed picture of family tree lines crisscrossing the world. It started as a fun way for genealogy enthusiasts to find new and distant family connections. But that's not where it ended. Let's delve into the unexpected coming-of-age of genealogical data, cold cases it helped solve, and where the technology might take us next.

How did we get here?

According to Science News, more than 12 million consumers in the US alone have submitted their DNA for testing. In the vast majority of cases, the draw is curiosity. Within weeks of sending in a spit specimen, you get a glossy report detailing all kinds of genomic revelations. You might learn you have distant cousins in Latvia. You may learn what you suspected all along—that your DNA possesses a few shreds of the good stuff from the legendary conqueror, Genghis Khan. You may even suss uncomfortable truths about extra conjugal intrigues from generations back in your family tree. It's all good fun, and it's shedding more light than ever before about our species' messy, chaotic, genetically haphazard march through history.

But all the genetic results collected by services like GEDmatch and 23andMe don't just add up to piquant family stories about Great-aunt Beryl and her brief dalliance with a Polish gentleman-caller back in times of yore. They also add up to big data—about as big as it gets. In April 2018, news headlines lit up with the first murder conviction using DNA evidence gathered through one of several popular genealogy sites, GEDmatch. As Topic Magazine aptly put it, the technology "exploded into public awareness." Since that first landmark moment, scores of violent offenders have been brought to justice. Law enforcement had stumbled into what may be the greatest tool for investigating violent crimes since the invention of fingerprinting: genetic genealogy.

Genealogical data takes down the Golden State Killer

On April 26, 2018 The Sacramento Bee reported that the Golden State Killer, an infamous murderer and sexual crime offender of the 1970s and 80s, had been identified and arrested. Joseph James DeAngelo, a former police officer, was taken into custody for crimes he'd committed half a lifetime ago. In his mugshot, DeAngelo looks baffled.

The public was baffled too, as they learned more about how the killer had been brought to justice. Sacramento PD investigators had taken the suspect's DNA from his crime scenes, but until 2018, it had been useless. Without a huge DNA database to match the Golden State Killer's unique genetic fingerprint against, investigators were groping in the dark. It was like having a criminal's fingerprints without a fingerprint catalog to compare it against.

GEDmatch changed all that. As described in The Atlantic, the process investigators used was similar to how an adoptee's biological parents might be found using a genealogical database. Investigators identified the killer's distant relatives using the vast database of DNA data in GEDmatch. Painstakingly, they narrowed their search down to DeAngelo, who had been living near where the crimes were committed. DeAngelo was investigated and charged with 13 counts of murder, among other serious charges. It was a landmark case, and a novel way to bring a murderer to justice. It was also just the beginning.

Genealogical data—a two-edged sword

The Golden State Killer case was the landmark case which brought genealogical sleuthing into the limelight, but this was only the first of scores of similar investigative breakthroughs. Genealogical data is a game-changer for one simple reason: the passage of time doesn't matter. A trail of conventional evidence goes cold. As time marches on, it becomes progressively harder to piece together what happened. Genealogical data doesn't work like that; in fact, the opposite is true. Humanity's DNA database is expanding rapidly, and with each new saliva specimen, dark secrets from the past become easier to root out. This new reality became crystal clear in May of 2019 when Seattle police announced they'd cracked a 52-year-old murder case, the oldest thus far solved through genealogy.

As reported by the Seattle Times, in 1967, a young Seattle woman was sexually assaulted and then strangled, her body abandoned in a parking lot. The killer was never found. In 2018, DNA from the crime scene was used to track down a potential suspect, Frank Wypych, deceased in 1987. His remains were exhumed, and a match was confirmed over 50 years after the crime was committed. The Wypych case revealed the powerful potential of genealogical data, but it also gave society ethical and emotional food for thought. It slices through the past of the guilty like butter, but can cut deep into the personal histories of innocent generational bystanders just as easily. Genealogical data is a two-edged sword.

New forms of genealogical sleuthing

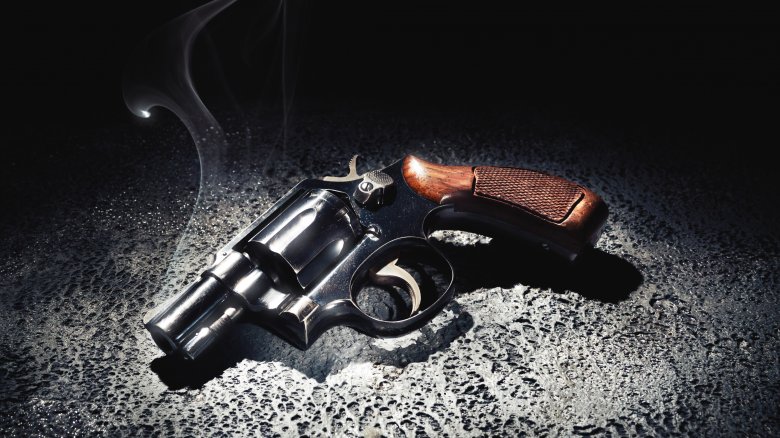

Whereas the smoking gun was once, well, an actual smoking gun, now the trail of evidence linking a killer to their victim is a second cousin, an unknown brother adopted out as an infant, great-great-grandparents even. And unlike a gun, your generational trail never stops smoking. The Sherlock Holmes' of our time aren't forensic crime scene savants. They're people who can use a scrap of DNA to weave artfully through generations of intricate familial data.

One such DNA sleuth is CeCe Moore, a genetic genealogist working with Parabon NanoLabs, a Virginia-based DNA technology company. Tasked with identifying a suspect for a 1986 murder and sexual assault, Moore found a promising genealogical lead: the murderer possessed Native American DNA. However, as described in a New York Times article, Moore hit a brick wall. While she had identified a first cousin and a scattering of distant cousins, something didn't add up. She could find no evidence of Native American ancestry. Then, as all good sleuthing stories go, she had her eureka moment. What if the family tree had misattributed paternity? Armed with that insight, Moore followed the suspect's ancestry through multiple generations, watching the history books bring the family line closer to the murder scene. Gary Hartman, a man who was not among the list of suspects in 1986, was charged with first-degree murder. It was another success for the good guys, but the case also showed how genealogical data can reveal uncomfortable family secrets.

The man who died alone

In 2001, a young man checked in to a tiny hotel in Washington. Days later, cleaning staff discovered him kneeling in the corner of his room, head bowed. The man was dead, seemingly of suicide by hanging. He had no personal effects to reveal his identity, or why he chose to end his life in a remote town on the edge of nowhere. The case soon went cold.

By the mid-noughties, social media had reared its head like an enormous, omniscient Demogorgon. Communities of sharp-minded amateur sleuths emerged, eager to sink their investigative incisors into mysteries large and small. One such digi-Sherlock stumbled on the Washington case, and for 12 years the mystery floated around Reddit. Leads were followed, theories were debated, but nothing concrete was found until 2017 when a Redditor reached out to the DNA Doe Project. Using a DNA sample, the project located a match. The family was approached, and finally, the Reddit community had a name for the man they'd been investigating for over a decade: Lyle Stevik. According to an article in The Outline, the moment was bitter-sweet. Stevik's family were hostile and guarded when asked questions. One Redditor wrote, "After all of the effort ... when no one else seemed to care: 'Mystery solved, but it's none of your business. Go home, folks.' That's a hard pill to swallow."

If you or anyone you know is having suicidal thoughts, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

Finding Annie with genealogical data

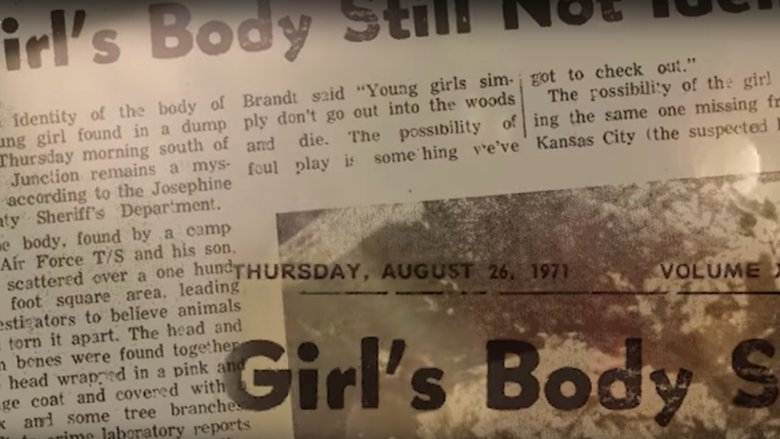

The Stevik case is an example of an unsatisfactory outcome for investigators. However, there's no shortage of examples of genealogical data bringing catharsis and emotional closure, especially for police investigators. In 1971, the bones of a woman were found scattered in the Oregon woods. The only clues investigators had were a map, some nondescript jewelry, and the ragged tatters of the clothes she had been wearing. It was a hopeless case. It was thought that Annie Doe, as she would later come to be known, would remain unidentified and without a family to mourn her.

The detective in charge of her case retired in 2012, but even in retirement he continued to work on her case. He couldn't let go of the questions of who she was and how she met her end. Then the Golden State Killer case broke, and genealogical data investigative techniques created new hope for a resolution. As reported by Inside Edition, in 2017, DNA was taken from Annie Doe's bones. The specimen was degraded, but it was enough to extract her unique genomic fingerprint, and the GEDmatch map lit up with family member results from all over the world. Annie Doe was, in fact, Annie Lehman. The detective was able to speak with Lehman's sister. While how she was killed and by whom remains a mystery, the detective could at least restore Annie Doe's real name and find some emotional closure through speaking with her family.

The Buckskin Girl

Genealogical data has become a game-changer for finding criminals and identifying victims, but the significance of these investigative techniques soaks far deeper into society's bones than mere crime and punishment. A cold case doesn't go cold for a missing person's family. In the absence of resolution, families can find themselves in a quagmire of not-knowing. This can span lifetimes, even generations.

In 1981, the body of a young woman was found dumped in a roadside ditch in Ohio. Dubbed the 'Buckskin Girl' for her deerskin jacket, the case had the hallmarks of a murder that should have been resolved swiftly. But her identity, along with the circumstances of her death, remained a complete mystery for 37 years. As ABC News reports, over the years, new forensic techniques were employed to aid in the investigation. Her nuclear genetic profile was obtained from her blood; facial reconstruction techniques were used to release an image of her likely appearance at the time of her death. Pollen studies were conducted on her clothing to determine her movements during the last year of her life. All these tools ultimately proved unsuccessful in breaking the Buckskin Girl case.

In July of 2018, the Troy Daily News reports that genealogical data gave the unknown girl her name back. After 37 years, the family of Marcia Sossoman was able to provide her with a burial and headstone.

An ethical storm in a paper cup

In 1987, a young couple was found murdered in Skagit County, Washington. Jay Cook was found wrapped in a blanket, while the body of Tanya Van Cuylenborg was discovered nearby. Investigators determined she had also been the victim of rape. The case frustrated investigators for over 30 years. As the Washington Post reports, ample forensic evidence existed, in the form of the couple's vehicle, the blanket, and DNA evidence. Moreover, over 300 names of suspects were offered by tipsters. Despite this abundance of leads, however, the couple's murderer remained at large.

In 2018, genealogical investigators used the DNA evidence to identify two of the murderer's cousins. Local law enforcement followed the suspect, looking for an opportunity to confirm the genealogical smoking gun. Eventually, they found it. A carelessly dropped paper cup was all it took to establish a DNA match. Police swooped in to arrest William Earl Talbott II, a man who had not appeared as a suspect despite reams of evidence collected through conventional investigative methods.

It was a notable win for the growing field of genealogical forensics, but the high-profile nature of this case also attracted criticism. Outspoken advocates for public privacy began to ask if it was ethical for family tree data to be used to investigate crimes without permission. Labs rejected the criticism, claiming it was based on a misconception about the process, and that only public data was used. Nevertheless, ethical battle lines were being drawn.

One step forward for a legal framework for genealogy

2018 and 2019 have been a Wild West frontier for genealogical crime investigation. The Golden State Killer breakthrough was just the first of many wins for law enforcement. Despite these coups, society is still struggling to play catch up with the ethical and legal implications of using crowdsourced genealogical data. In 2019, one state movedcloser to a legal framework with the passing of Washington's Jennifer and Michella's Law. Named for two murder victims whose cases were broken using genealogical data, the law enshrines new uses for DNA in cracking violent sexual crime. As K5 News reports, thanks to this legislation, DNA samples can now be collected from deceased sex offenders. This, along with similar legal provisions, increases the pool of genealogical data the state's law-enforcement officers can use to crack future crimes.

This is the first major legal bid to formalize the collection of DNA to aid in future criminal prosecution. It also represents society taking one step closer to accepting genealogical data investigation methods as a key tool for law enforcement.

One step back

Around the same time Jennifer and Michella's law was passed to embrace genealogy into the core of investigative practice in one state, an incident occurred which sparked a strong negative response from the public. In April of 2019, an elderly Utah woman was physically assaulted in a church. Blood from the scene was used to identify the assailant. This represented the first time genealogy had been used to solve a case that was not murder or rape.

The use of genealogical data to solve this case represented a violation of GEDmatch's terms of service, but the service's founder, Curtis Rogers, decided to make an exception given the severity of the attack. The criminal was caught, and GEDmatch proclaimed this as another step toward a safer society. But the public's reaction was less favorable. According to CNN, many GEDmatch customers vehemently objected. The privacy backlash led GEDmatch to beat a hasty retreat, setting in place stricter provisions significantly curtailing the ability of police forces to use this data to catch criminals. Cece Moore, one of the investigative genealogists working the assault case said of Rogers' questionable decision, "People will die. It sounds dramatic but it's actually true." It was the first clear example of GEDmatch arguably taking one step too far.

The case for genealogical crime investigation

At first glance, the benefits of solving cold cases using genealogy seems like a no-brainer. What's there to discuss? The closure it brings to victims' families—not to mention its ability to put dangerous people behind bars—has to be a good thing, right? If we agree as a species that justice is a common good, shouldn't we legislate to make as much use as we can of this new and powerful weapon that just serendipitously fell into our collective lap?

Sure, GEDmatch made a questionable call when it stretched its terms of service to aid in the investigation of assault. But you could just chalk this misstep, and the raised eyebrows it elicited, as growing pains. This is new stuff for us. It's inevitable that boundaries will be pushed and buttons will be pressed while society and technology find some kind of equilibrium. And look at how the Golden State Killer was brought to justice. That guy would never have been caught without this technology. Or what about the case of the Buckskin Girl, whose family could finally mourn her after 37 years of not knowing? The arguments in favor of genealogical crime investigation are powerful because they're simple. This technology solves unsolvable crimes, and gives victim's families a chance at closure.

The case against genealogical crime investigation

Nevertheless, the use of genealogy data by law enforcement poses some difficult ethical questions. First, there's the big, shifty-lookin' elephant in the room: how far is too far? As the assault case in Utah revealed, there's a blurry and shifting line between crimes that should and should not be investigated using the genealogical technique. Sure, not many people out there are going to argue rape and murder cases should be investigated using genealogical data. But assault? And as this New York Times article points out, if we do collectively agree with the genealogical investigation of serious assault cases, when does that seep down into shoplifting? Or trespassing?

Then there's the issue of consent, and here it gets really wobbly. Sure, genealogical data warehouses can slap some consent tick boxes on their online data submission forms, and this at least pays lip service to the idea the person submitting their DNA is cool with it being used in crime investigation. But DNA doesn't work like that!. It's not like an ATM pin number. The same genetic data is shared across entire families, the vast majority of whom have no say in how their data is being used. Today, we're living in the genealogical data equivalent of the Wild West, where (almost) anything goes. The next few years are going to place some curly questions in our path.