The Untold Story Of Russia's All-Female Battalion Of Death

War is hell, but hell hath no fury like the Women's Battalion of Death. One of Mother Russia's forgotten offspring, the battalion was conceived by "Russia's Joan of Arc," Maria Bochkareva, and born in 1917. The stakes couldn't have been higher. Nothing was quiet on the Western front or the home front as World War I raged and Bolsheviks waged a revolution. Amid the din of warfare and upheaval, the battle cry of Russia's male soldiers became a whimper. So Russia's female warriors came roaring onto the battlefield like an army of Grim Reapers eager to snatch enemy souls. In the process, they inspired other women to mobilize.

While Mother Russia faced chaos on two fronts, her fighting daughters confronted destruction on three. They clashed with foreign adversaries, defended against homegrown revolutionaries, and came under unfriendly fire from male Russian soldiers. Even getting permission to fight was an uphill battle. Unfortunately, those women lost their fight for equal treatment. However, while history is written by the winners, making history isn't about whether you win or lose but how you give 'em hell.

The Women's Death Battalion and the fight for women's rights

All-female death battalions don't happen in a vacuum, and they didn't happen at all in Russia before 1917 because society sucked for women. Whether they lived on the upper crust or lived off crumbs at the bottom, they didn't have the right to vote or hold public offices in Russia, per the British Library. Obviously, wealth afforded certain opportunities, like the ability to obtain a limited education. Power-wise there were historical exceptions like the exceptional Catherine the Great, but even she became the target of sexual myths meant to undercut her accomplishments. By and large Russia's women were denied independence, and most were illiterate peasants.

In the 1860s and '70s, many women embraced a populist ideology that demanded social justice and which later gave rise to the Bolshevik uprising. WWI intensified their fight for equality. As men went off to dig trenches, women began carving their own path in the workplace and demanding a place in the military. Per Smithsonian, multiple women, like Maria Bochkareva, who later created the Death Battalion, initially fought alongside male soldiers. In 1917, likely on International Women's Day, Petrograd became the stage for the largest women's protest in the nation's history. Later that year, women won the right to vote and began organizing all-female battalions. Bochkareva's Battalion of Death was the first and most notable, but War History Online notes that 15 women's battalions formed, and two saw combat.

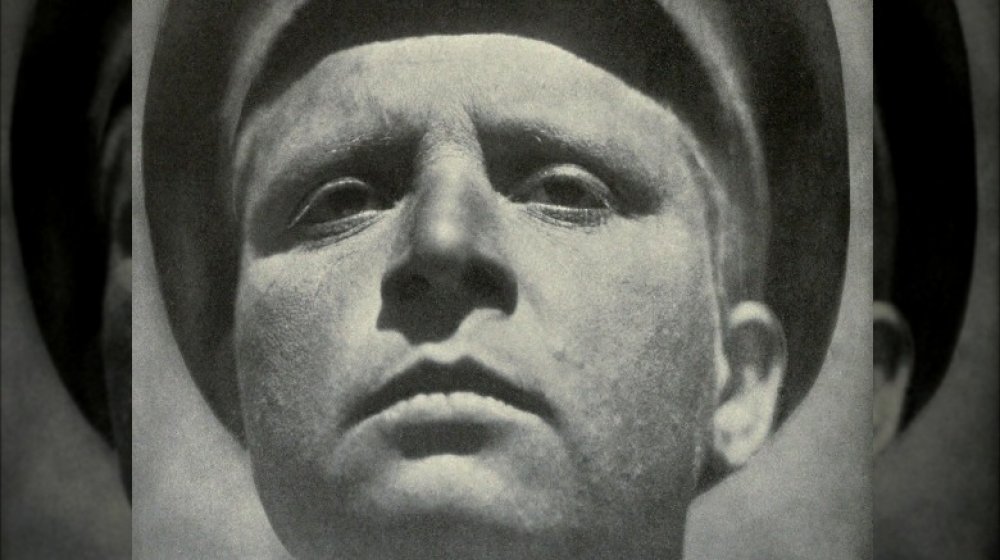

The Death Battalion's founder endured horrific abuse and hardship

The story of the Women's Battalion of Death began and in many respects ended with Maria Bochkareva (above). As described in her autobiography, she was born into poverty in 1889. The daughter of a decorated soldier and army sergeant, Bochkareva recalled her father as a "morose and egotistical" man who became a cruel-hearted alcoholic. He violently terrorized the family and then abandoned them for five years. In his absence, Bochkareva, along with her mother and two older sisters, nearly starved. When he returned, so did the violence, and their severe financial hardship only got harder with the birth of a fourth child.

At age eight Bochkareva spent her nights sleeping in a baker's horse stable and was forced to take care of a 5-year-old boy to avoid eviction. By age 15 she lived in her parents' basement. "My father would come home drunk almost every day, and immediately take to lashing me," she wrote. He forced her and her mother to spend hours outside in the ice and snow. Desperate to escape, she married Afanasi Bochkarev, who turned out to be a belligerent alcoholic. When Bochkareva attempted to escape him, Afanasi tied her to a post, flogged her for hours, and force-fed her alcohol under threat of death. She eventually fled and became romantically involved with a man who later tried to murder her.

An army of harassers

Before commanding Russia's first women's battalion, Maria Bochkareva joined an otherwise all-male outfit. During that time, she adopted the moniker "Yashka" as an apparent nod to her second, common-law husband, Yakov "Yasha" Buk. "That name [Yashka] stuck to me ever after, saving my life on more than one occasion," Bochkareva remarked. But the man who inspired that nickname almost killed her. A gambler and jailbird, Yasha tried to hang Bochkareva in a "cold, business-like" fashion when he suspected her of infidelity. Fearful of her husband's homicidal wrath, she resolved to fight in WWI in 1914, seeing it as more noble to leave her husband to "help save the country" than to save her own life.

Bochkareva's request to join the military was initially rejected, according to scholar Angela Shpolberg. It took a personal appeal to the tsar to gain admittance, and gaining acceptance from male recruits was a war in itself. Many didn't respect her as a person, let alone a potential soldier. "They proceeded to pinch me, jostle me, and brush against me," she recalled. At night she had to combat an onslaught of unwanted hands and arms extended by men intent on violating her. One night her squad commander harassed her, and Bochkareva slugged him. As punishment for defending herself, she had to stand at attention for 26 hours instead of the standard 24 for guard duty.

The Women's Battalion of Death was meant to shame men into fighting

Bochkareva didn't just fight next to men in WWI; she outfought them. As recounted in Yashka: My Life as a Peasant, Exile and Soldier, during her first taste of trench warfare, her regiment was reduced from 250 to about 70 people. Surrounded by wounded men, she braved the treacherous No Man's Land to rescue as many injured soldiers as she could. She carried casualties to the edge of the trench so others could bring them to safety and "saved about fifty lives" by the following dawn. Over the course of the war she incurred battle scars of her own.

Once "a huge German" shot Bochkareva in the leg. After returning to the western front she got struck in the back by shrapnel from an exploding shell, leaving her paralyzed for four months. Over the course of her exploits she received three medals for bravery, per Smithsonian. Despite the agony and accolades, she didn't rest in bed or on her laurels. But by May 1917, Russia's male soldiers were refusing to fight. Dwindling morale spurred mass desertions on the Eastern front. So Bochkareva met with Minister of War Alexander Kerensky and proposed trying to shame them back into battle by assembling an all-female battalion that she would command. Bochkareva reasoned, "Since our men are hesitating to fight, the women must show them how to die for their country and for liberty."

The women took vows of chastity

On May 21, 1917, as Russia faced an epidemic of fleeing soldiers during WWI, Maria Bochkareva unleashed a rallying cry that rippled through Russia: "Our mother is perishing. Our mother is Russia. I want to help save her. I want women whose hearts are pure crystal, whose souls are pure, whose impulses are lofty." For Bochkareva, sexual "purity" was of the essence. Of the 2,000 women who answered her call to arms, she claimed she "sent away 1,500 women for their loose behavior" such as flirting with instructors.

As described in Battle Cries and Lullabies, women in the Death Battalion were "required to take an oath of chastity," as were female nurses. Bochkareva took this vow so seriously that when she discovered a member of her battalion making love to a male soldier behind a tree, the commander snapped like a deranged twig. "I was almost out of my senses," she said of the incident. Her boiling blood turned her heart into "a raging cauldron" and she bayoneted the woman to death.

The Death Battalion vowed to die rather than be captured

The Women's Battalion of Death lived up to its joyless moniker. Author Linda Grant De Pauw explained that female recruits were dismissed for giggling and slapped for lack of discipline. Writer Helen Rappaport wrote that "they drilled hard, for six hours a day, like male recruits, and dug trenches." Supply shortages forced many of them to wear normal shoes instead of army boots. These laughless, bootless soldiers marched into battle ready to fight to the death.

As detailed in The Last Days of the Romanovs, the women carried vials of lethal "potassium cyanide in case of capture and rape." Though, they may have been too busy taking lives to worry about being taken prisoner. In 1917, a correspondent for UPI described the Death Battalion as "good killers." One member kept the helmet of a German soldier she had slain as a souvenir.

The good killers also excelled at capturing enemy combatants, some of whom were German women that joined the fray. Leading the way was the battle-tested Maria Bochkareva. As one woman put it, "Commander Bochkareva was everywhere in our midst, urging us to fight and die like real Russian soldiers." One soldier mistakenly believed that Bochkareva lost all regard for her own safety and searched for the commander amid a barrage of exploding shells. The devoted soldier was "blown to fragments."

The death of the Death Battalion

The Petrograd Women's Battalion was "a copycat of [Maria] Bochkareva's Battalion of Death," according to War History Online. When Anna Shub enlisted in Petrograd's unit, she had the best of intentions. "I left everything because I thought the poor soldiers of Russia were tired after fighting so many years, and I thought we ought to help them," she said in an interview. When she realized they "were supposed to be shaming the soldiers" she felt like "[dying] of shame." Another battalion member lamented, "We expected to be honored, to be treated as heroes, but always we were treated with scorn" by male soldiers.

A similar hostility spelled the death of the Death Battalion. Despite fighting courageously, Bochkareva's band of killer women triggered dismissiveness and murderous rage in male soldiers. Per her autobiography, when the women's battalion needed backup after gaining ground and suffering heavy losses in battle, the resentful men mocked Bochkareva's squad and refused to assist. "The women will fight!" and "Just watch those women run!" they cried. After a successful Bolshevik rebellion back home, Russian men on the Western front rebelled against Bochkareva and her battalion, shouting, "Kill her! Kill them all!" Four instructors who tried to protect the Death Battalion were trampled to death by a vicious lynch mob that murdered 20 women. Harvard associate and Brandeis University scholar Angela Shpolberg explained that following the incident, Bochkareva's squad secretly disbanded.

The women at the Winter Palace

1917 marked a sea change when the Bolsheviks toppled Russia's provisional government, ushering in the Soviet era. Some sources, such as the Vintage News and Spartacus Education have claimed that Bochkareva led the final line of defense against the Red Army when it sacked the Winter Palace in Petrograd. But according to Bochkareva's own memoir, she was away being betrayed by Russian men on the Western front when the palace fell. War History Online clarified that it was actually the Petrograd Women's Battalion — which emulated Bochkareva's squad — that attempted to beat back the Bolsheviks.

Unfortunately, for the Petrograd unit, it was a doomed effort before it even began. As Deutsche Welle detailed, by the time the Red Army made its move, the palace was largely unguarded. In fact, many of the men charged with guarding the building had switched allegiances, aligning themselves with the Bolsheviks. The battleship Aurora kicked off the killing by training its cannons on the Winter Palace and opening fire. Some contemporaneous accounts alleged that most or all of the female soldiers were raped and in some cases thrown from windows. Unsurprisingly, the young Bolshevik government cleared itself of the bulk of those accusations.

How two pro-Soviet Americans helped frame the narrative

The University of Indiana's Slavica Publishers wrote that "of all of the books by American witnesses of the Russian Revolution, John Reed's Ten Days That Shook the World was and still is the best known." Per Eyewitness History, when Reed traveled to Russia to cover the Russian Revolution, "he immediately embraced the Bolshevik cause and was welcomed into the movement." But he was loath to embrace claims that were critical of the Red Army. When the proto-Soviets were accused of raping most of the Petrograd Women's Battalion and throwing some of them from windows, Reed seemed intent on discrediting the accounts, writing them off as "sensational stories" by "the anti-Bolshevik press."

Reed's wife, Louise Bryant, interviewed members of the Petrograd Women's Battalion and documented her observations in Six Red Months in Russia. She, too, dismissed allegations of assault, proclaiming, "I didn't believe it, but I wanted to assure myself." At least one female soldier confirmed that she'd been shoved through a window, but she claimed her assailant was remorseful and "cried like a baby." Of course, the Red Army was in charge now, so accusing them of malice might have seemed unwise. Nonetheless, it seemed to mollify Bryant. It's worth noting that Bryant described the Russian Revolution as "one of the best arguments I know in favour of women's suffrage." So she might not have wanted to see the suffering of women harmed by the revolution.

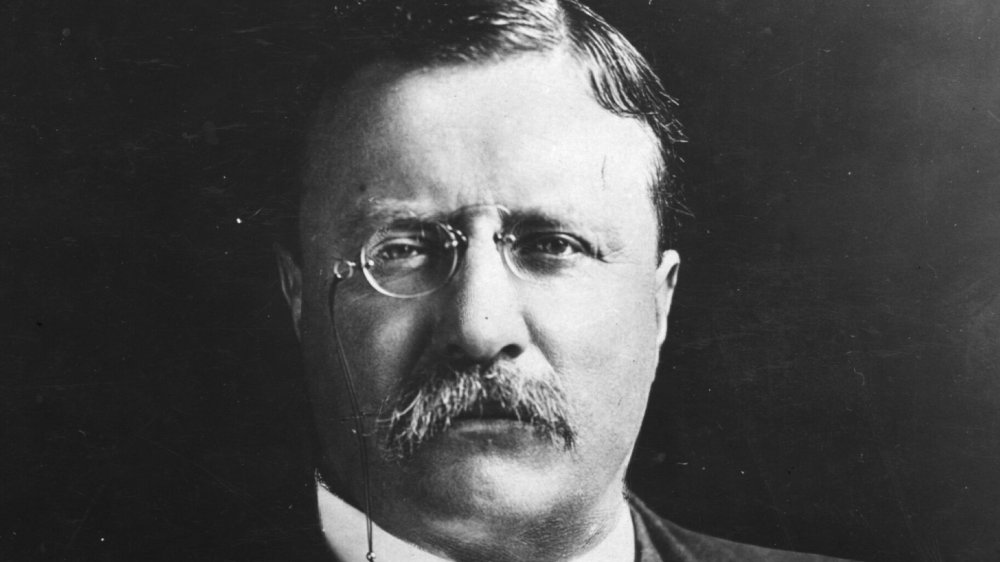

Russia's Joan of Arc meets America's Teddy Bear

After the dissolution of the Women's Battalion of Death, Maria Bochkareva continued to serve her country during the Russian Revolution. As outlined in Angela Shpolberg's "Women with the Gun," Bochkareva had no desire to take up arms against any Russian. However, when a civil war broke out between the pro-Bolshevik Reds and the anti-Bolshevik Whites, she agreed to collect intelligence for the Whites. The Reds arrested her and sentenced her to death. Luckily, one of the local Bolsheviks was a former Imperial soldier whom Bochkareva had saved in battle, so the soldier returned the favor and secured her release.

Bochkareva used her new lease on life to petition foreign allies for help in overcoming Germany in the ongoing world war. She met with England's King George V, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, and the iconic former president/future Mount Rushmore resident Teddy Roosevelt. Roosevelt frowned on the idea of female soldiers, but he admired Bochkareva's "remarkable character abounding in natural wisdom and determination." According to Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life, "he wrote that he 'hated [his] impotence to help her'" and encouraged President Wilson to intervene in Russia's Civil War. Roosevelt was so moved by his description of the hardships suffered by the women of the Death Battalion that he gave Bochkareva $1,000 of his own Nobel Prize money to help them.

The red death of Maria Bochkareva

In 1917, Maria Bochkareva found herself caught between a world war, a looming civil war, and militant misogynists. A mob of enraged Russian men on the Western front saw to it that No Man's Land would become No Woman's Land by lynching Bochkareva's Death Battalion and prompting its dissolution. And after the Bolsheviks ran roughshod over the Winter Palace, many of the women whom Bochkareva inspired to fight now fought against her. According to scholar Angela Shpolberg, they decried her as a tool of the "bourgeois" Provisional Government and accused the commander of leading them astray.

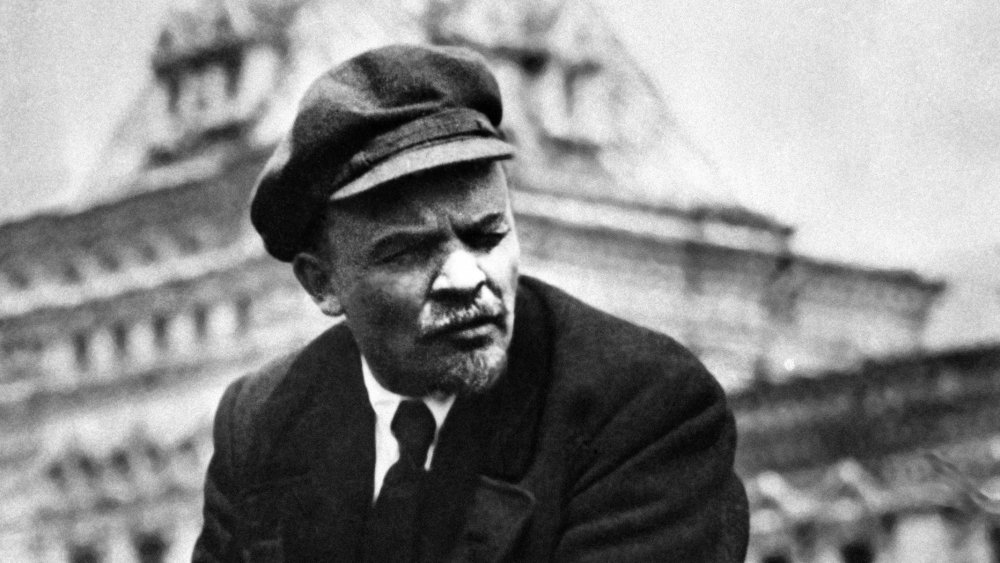

Bochkareva later lashed out against the women who now disavowed her, claiming that "women are, with few exceptions, unfit for warfare" and that some of the females who served under her in war ultimately betrayed her. She also made enemies in high places. Founding fathers of the USSR Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky perceived Bochkareva as a threat and personally interrogated her. She presented herself "as simple peasant woman, not interested in politics" and not opposed to an egalitarian society. However, she repeatedly ran afoul of the leaders by attempting to aid the anti-Bolshevik White Army. She escaped execution once but wouldn't cheat death a second time. While trying to organize a female sanitary brigade for the White Army she was apprehended. The Bolsheviks branded Bochkareva an "enemy of the people" and executed her in 1920.

The unfortunate fate of the women's battalions

Neither the Women's Battalion of Death nor the units that followed suit managed to shame men into battle effectively. Nor did the women's valiant battlefield efforts raise men's morale, according to War History Online. Instead, females faced widespread sexism. The government tried to sideline them by assigning most of the women to non-combat tasks like guarding railroads. But men objected to that, too, whining that the women were taking their jobs and forcing men to fight.

Once the Bolsheviks took over, they canceled the women's battalions altogether. Some of the units complied instantly. Others would stand their ground before being stamped out of existence. Some would participate in the Russian Civil War. However, the end is never really the end when it comes to history. And the Women's Battalion of Death would end up becoming a Soviet-style propaganda tool for Vladimir Putin's government. Indie Wire reported that in 2014, the Russian government memorialized WWI with a film celebrating Maria Bochkareva and her ill-fated squad.