Things The Aeronauts Got Wrong About History

The magic in The Aeronauts, starring Eddie Redmayne and Felicity Jones, seems as strong as the actors' earlier pairing in The Theory Of Everything. In The Aeronauts, Redmayne plays the real-life scientist and meteorologist James Glaisher, while Jones is Amelia Wren.

But when Tom Harper made this movie inspired by true events, he forgot to mention the inspiration was cloudy. Almost murky. Like not remotely close to the truth. The Aeronauts is a good movie ... if factual accuracy isn't your thing. Ballooning was the only way people in the 19th century got their kicks, in the name of adventure. As cool it was to see people ascend to the heavens, having them fall to their deaths made for a good spectator sport. Human beings are a blood-thirsty lot after all. So ballooning was fun but balloonists dying was even more fun.

The cheering crowd, as the balloon launches, captures that morbid excitement. While The Aeronauts manages to get the spirit of ballooning of the 1800s, it gets many facts wrong. It's not a mistake, it's a deliberate oversight. Call it artistic license. So here is all that is wrong with The Aeronauts. (Warning: spoilers ahead.)

The Aeronauts' Amelia Wren is completely made up

The main character in The Aeronauts is the sullen and proper James Glaisher, a scientist hell-bent on proving his point about weather forecasting. Played by Eddie Redmayne, James Glaisher is based on a real-life character who did achieve all that he set out to. The perfect foil to his single-mindedness is Amelia Wren. She is a balloonist but more than that, a performer. She does backflips and enchants the audience. There are fireworks and puffs of color. Once high enough, she throws a dog down to the audience. The audience thinks the pooch is a goner, but then a parachute opens and down it lands on terra firma.

The only downside to a feisty Felicity Jones playing Amelia Wren is that there was no Amelia Wren. No balloonist by that name, and no PT Barnum-type entertainer either. Not to say that there weren't any female balloonists at that time, because, as Atlas Obscura notes, there were. But they were unlikely to be this flamboyant, or as winsome as Felicity Jones makes her character out to be in The Aeronauts. So with Amelia Wren out of the picture, all that Glaisher-Wren romantic tension is moot. More's the pity.

The real life James Glaisher was no movie star

In The Aeronauts, Glaisher and Amelia Wren seemed to have a budding romance, especially when they are up in the air. In the beginning, The Aeronauts shows Glaisher is absorbed by his instruments. He diligently records every little change in the atmosphere as they begin to rise, barely looking around himself. He is disapproving of her antics; she finds him a tad amusing.

But there is an undercurrent of attraction shown between them. Like in the way they steal glances at each other. Or how Wren likes Glaisher though she is still mourning her dead husband. As they rise and fall with the air currents, their attraction and mutual respect only grow.

Even ignoring the fact there was no historical Amelia Wren, there wasn't any other female in that balloon with James Glaisher, either. The reality is, the actual James Glaisher in 1862 was a far cry from the spry, attractive Redmayne. He was 52, and according to his great-great-great niece, already married, so he wouldn't be so improper as to go off with a widow in a balloon. It's all just for the story. It does make the movie a more interesting watch, of course, much like Jack and Rose in Titanic. But like Jack and Rose, there was no James and Amelia either.

The Aeronauts pretends Henry Tracy Coxwell didn't exist

The perilous 1862 balloon flight was real, and the movie does not err in putting James Glaisher in the balloon. The reality had no Amelia Wren, but the Telegraph reports a Henry Tracy Coxwell was with Glaisher. Coxwell was an important balloonist as well. Unlike Wren, he didn't do backflips or shoot off fireworks. He did take a scientific flight with Glaisher and ascend to unprecedented heights of 37,000 feet, a record at the time for manned flight.

There's even a photograph of the Glaisher and Coxwell sitting in their balloon in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery in London. It does what the movie doesn't, commemorating and honoring the two men who made history that day.

Sadly, The Aeronauts blows Coxwell away in a gust of wind and overthrows everything he did to make history. As opposed to a brave Amelia Wren, it was a brave Coxwell who saved Glaisher's life that day, even if the reality wasn't quite as dramatic. In order to add a female main character and a hint of romance, the real Coxwell is missing. In his stead, is the fake but winsome Amelia Wren. While the writers call this artistic license, it's akin to showing the Wright sisters instead of the Wright brothers.

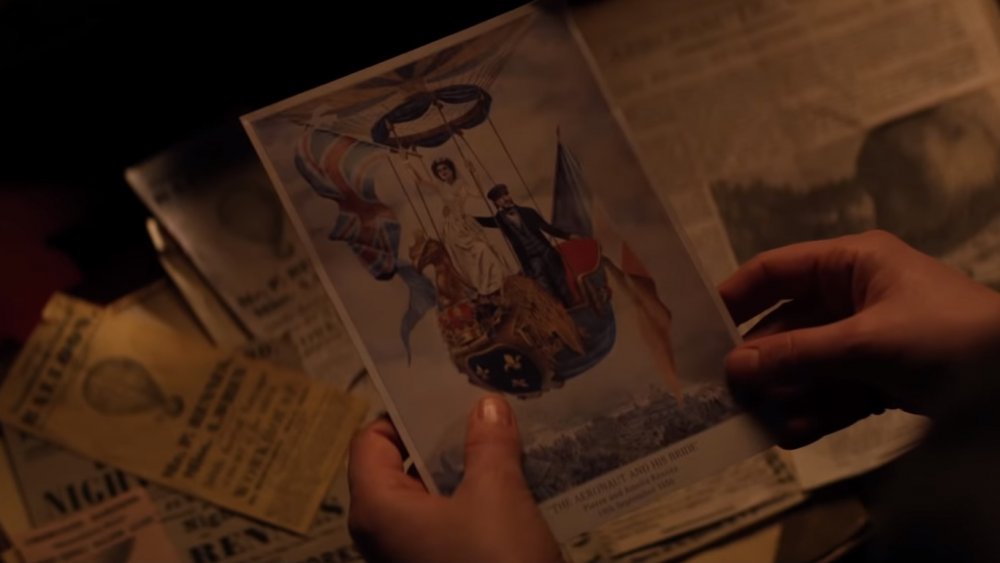

Amelia Wren was based on balloonist Sophie Blanchard

There were female balloonists even in the 1800s. According to Smithsonian, one of them was Sophie Blanchard. Ms. Blanchard was a small woman with sharp features who was afraid of even carriage rides. But when her husband, balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard took her up in a balloon, she was smitten. No, not by her middle-aged husband who took her as his second wife, but by ballooning. From then on, she reveled in ballooning, even flying solo at times.

Blanchard was French, and Napoleon Bonaparte and King Louis XVIII gave her awards and titles for her flying feats. She made an accent to celebrate Napoleon's 42nd birthday in 1811, and when the French aristocracy came back to power in 1814, Louis XVIII made her "Official Aeronaut of the Restoration."

Blanchard seemed uncaring of the danger. In those days, balloons flew on hydrogen gas. Since hydrogen is lighter than air, the balloons would rise. But Blanchard (and her husband) would sometimes light fireworks around the balloon, even though she knew the hydrogen could catch fire. (This would, in fact, eventually be the cause of her death.) Fear didn't seem to be part of her character. It's a notable difference from the debilitating flashbacks Amelia Wren keeps having in The Aeronauts.

The Aeronauts' Pierre Rennes was based on Jean-Pierre Blanchard

In the movie, Amelia Wren and her balloonist husband Pierre Rennes are on a balloon when things go wrong. The balloon is descending too fast and the couple tries to save themselves. They throw all that they can out of the balloon to make it lighter. When Pierre sees nothing is working, he heroically jumps off the balloon and falls to his death, sacrificing himself to save his wife.

The woman Amelia Wren takes inspiration from, Sophie Blanchard, was half of a real-life balloonist couple. And according to the Encyclopedia Britannica, her husband, Jean-Pierre Blanchard, did die due to a fall from the balloon, just not so heroically. Jean-Pierre suffered a heart attack mid-air as he stood near the edge of the basket. Floundering, he toppled off the balloon and eventually died from his injuries. Nothing of this saved or helped his wife, Sophie. Instead, it left her with a mountain of debts that she repaid with her ballooning jaunts and aerial displays.

Jean-Pierre Blanchard was also no hero, unlike Pierre Rennes. Smithsonian says he falsely claimed to be the inventor of balloons and parachutes. He abandoned his first wife and four children. He then married Sophie, a woman much younger than him. He established an academy, which tanked. In massive debt, he persuaded his wife to fly with him to draw bigger crowds, but he still left her in major financial trouble when he died.

James Glaisher and Sophie Blanchard probably never met

In The Aeronauts, Amelia Wren survives numerous ballooning disasters. In the first incident, it's her husband who dies. Later, she is ready to sacrifice herself to save James Glaisher. As the balloonist, she believes it to be her responsibility as a pilot. Plus she refuses to be responsible for another person's death. With her husband dying still a sore point for her, Wren is okay making the ultimate sacrifice. She survives in the end, but real-life balloonist Sophie Blanchard wasn't so lucky. Despite having made a good life for herself after her husband's death, Sophie Blanchard's last flight was when she was 41.

July 6, 1819, saw her planning a "Bengal Fire" demonstration at Tivoli Gardens in Paris. According to Smithsonian Magazine, she said, "Allons, ce sera pour la derniere fois." Translated, it means: "Let's go, this will be for the last time." Tragically, if she was predicting her own death, she was right. The balloon caught fire and the fast descent caused the basket to crash into a building. Blanchard tipped out and fell onto the street below. She was dead by the time anyone reached her.

This was 1819, and James Glaisher was only born in 1809. So he was ten when Blanchard died and they likely never met. The romance is complete fiction, in more ways than one.

James Glaisher did not beg for an expedition

The derisive treatment Eddie Redmayne's Glaisher meets with at the scientific "boys' club" in the film is all fantasy. According to Smithsonian, Glaisher was, in fact, an established scientist of his time. Born in 1809, James Glaisher became the first assistant to Professor George Airy at the University Observatory in Cambridge at only 24. Soon after, he was appointed to the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, where he became the first Superintendent of the Magnetic and Meteorological Department. In 1849, long before his historical balloon flight, Glaisher became a Fellow of the Royal Society, aged just 40.

He wrote more than 120 papers about meteorology in the United Kingdom and took some 28 balloon flights in total. Plus Glaisher was key in founding the Royal Meteorological Society in 1850. He was also a council member of the Royal Aeronautical society from its founding in 1866 until his death in 1903.

This was not a man who needed to beg others for a balloon ride. As an established scientist, well-respected in his circle, Glaisher was always lauded for his perseverance and passion. The BBC reports he persuaded the British Association for the Advancement of Science to fund his balloon trips. But he never needed to beg or face ridicule as shown in The Aeronauts.

The Aeronauts' John Trew isn't a real character either

In The Aeronauts, Glaisher's best friend is John Trew, played by actor Himesh Patel. Patel's ancestral roots may be from India, but he was born in England. To a 21st century audience, he's obviously English. But to the Victorians of the film, he wouldn't be.

In 1862, there would not have been any chance of the Royal Society accepting someone from India, even with an Anglicized name like John Trew. In the 1800s, racism was all too real. It was a blue-blood white boys' club, and even smart but lower class white people wouldn't get in. As the director of the film explained, "There would never have been an Indian man in the Royal Society. But representation is important, and we are cutting this film for a modern audience." So yes, there was no John Trew in real life, just in The Aeronauts.

(A much more accurate movie portrayal of the experience of an Indian in Britain is The Man Who Knew Infinity. In it, Dev Patel plays mathematician Srinivas Ramanujam, the guy who contributed to the infinite series and much more.)

The Aeronauts shows butterflies at 19,400 feet

There's a scene, early on in The Aeronauts, where Amelia Wren begins to recite a verse from Edmund Spenser's "The Fate of the Butterflie," which James Glaisher completes. The scene, as they say, is set. A storm breaks above them. High winds, clouds, and thunder buffet the balloon, making for a wild ride for Glaisher and Wren. Glaisher smashes his forehead while Wren is almost thrown out of the balloon. Glaisher manages to rescue her just in time. To save themselves, they begin to ascend further. Suddenly, they break through into the sun, sailing above a vast, fluffy sea of clouds.

Maybe it's cynical to not believe in happenstance, but The Aeronauts takes the cake. At 19,400 feet, a butterfly lands on Wren. And then more, and more till the sky is busy with a flock of yellow butterflies. Most butterflies aren't such high fliers. According to Telluride Magazine, the highest-altitude flying butterflies restrict themselves between 11,000-14,000 feet. The Monarch butterfly, for example, has only been spotted as high as 11,000 feet.

The Smithsonian Institute reports some butterflies have been spotted at 20,000 feet, though. So you could maybe stretch your suspension of disbelief that far. It's just that they were a little too convenient to add to the growing intimacy between Glaisher and Wren. Which of course, never was.

The Aeronauts' balloon did not take off from London

James Glaisher was the ripe old age of 53 during the flight immortalized in the film. But Glaisher as played by Eddie Redmayne does not seem to be a day older than 35. So the movie plays around with timelines. Of course, since Amelia Wren was never real, there was no supposed romance. In fact, according to BBC, some of Glaisher's family was "horrified" with the flights of fancy shown in The Aeronauts.

There's another major detail fudged up in the movie, more literary license taken to make it an interesting watch. The balloon flight did not take off from London as depicted in the movie. The reason was simple: if they drifted off course and fell, they could have drowned in the Thames.

The flight took off from the far less iconic Wolverhampton, and this was crucial for safety. Replace the fictitious Amelia Wren with the real Henry Coxwell, and other details are true. The balloon was named "The Mammoth." It did rise to 37,000 feet. The pair did so without the aid of bottled oxygen, for the sake of keeping the weight in check. History was definitely made on September 5, 1862, just not the same history shown in The Aeronauts.

No one climbed on top of the balloon to save James Glaisher

In the movie, James Glaisher passes out at between 29,600-32,400 feet from hypoxia (lack of oxygen), and what the BBC explains is a high-altitude version of the "bends" divers can get. Amelia Wren then performs a superhuman feat, the kind Wonder Woman would be proud of. When she tries to let out air from the balloon, Wren discovers the gas valve is stuck. To save their lives, she climbs up the netting on the side of the balloon, all the way to the very top, her fingers frostbitten. She kicks the gas valve until her boot gets stuck in it, and hydrogen finally begins to leak.

After this herculean effort, she passes out, right on top of the balloon. As the air leaks out, she slips and falls into space, waking up from the shock. Thankfully, she had tied herself to the rigging. Then she passes out again, only to find herself hanging upside down near the balloon basket. When calling for Glaisher does not help, Wren manages to swing herself into the basket with astonishing agility.

In real life, Glaisher did pass out that high up. And the BBC reports Coxwell did save his life. As Coxwell's hands were frostbitten, he yanked the valve-release rope with his teeth. Dramatic, sure, but there was no climbing up the balloon, so not half as exciting as The Aeronauts.

The actual landing was less dramatic than the one in The Aeronauts

Towards the end of The Aeronauts, the balloon is descending too quickly. Falling, really. Both Glaisher and Wren swing into action to save their lives. Everything not necessary, including coats, gets dumped. When nothing seems to work, Wren prepares to jump as the last resort. Just then, Glaisher has an epiphany. He says they can cut the cord of the balloon. The fabric would lose shape, rise on top of the netting, and work as a parachute. When Wren says it might not work, Glaisher says its either both of them or neither of them. The landing is rough, and Glaisher seems to be hurt worse than Wren. But they smile at each other and the romance is firmly established.

For the actual September 5, 1862 flight, things weren't as alarming. The landing was a little rough but still okay. As stated by the BBC, they landed in a field at a place called Cold Weston. Glaisher and Coxwell walked to the train station, but there were no trains. So they went for dinner, only to be disappointed by the food. Glaisher then telegraphed their location and the news of the men's success came out on September 11, 1862, in The Times. So the adventure was all there, but there was none of that romance. But yes, even for Glaisher and Coxwell, the skies did lie open.