Infamous Events That Never Actually Happened

War, famine, pestilence, and death: The four horsemen of the apocalypse, or just another day in global news? With doomscrolling practically an Olympic sport, it's easy to fall into the pattern of thinking the end of the world is just around the corner (or waiting right after the next news feed refresh). But for what little comfort it's worth, people have been expecting planet-destroying calamity for centuries, and they've usually been wrong. Not always, of course, but many warnings of coming disaster have turned out to be based on lies, scams, bad science, or plain old ignorance.

Poisonous comets, cataclysmic computer bugs, and the somehow-predictable wrath of God have all caused a panic or two in their day. Typically, they sent the pessimistic and gullible into fits and let the unscrupulous cash in on their anxieties. So cheer up: There's every chance that, when the world does end, it will be from something we never saw coming.

Y1K

Scholars disagree, as they often do, on the exact scale and shape of the reaction, but it seems likely that there was at least some panic in Christian Europe about the year 1000 marking the return of Jesus. His purpose? To, among other activities, judge the sinners of the world. There were disasters before this time, too: Vesuvius erupted, a plague ran rampant, and a fire hit Rome. But it was the year 1000 that sent jittery aristocrats donating to the influential monastic center at Cluny in France — sort of a carbon offset for the soul. The Holy Roman Emperor himself was also reputedly a mystic, or thought he was, which probably did little or nothing to calm things down.

There doesn't seem to have been much reason behind choosing this particular year except the fact that it's an obviously satisfying round number and a "milennium" is referenced repeatedly in the Book of Revelation. Translations and interpretations don't agree on what the milennium really means or when it might start (Revelation is a hallucinatory fever dream written in Greek, so its interpretation depends a lot on any given reader's literal-mindedness and what version they're reading.) As you may have noted, the world didn't end in or around the year 1000, leaving some people visibly disappointed.

The Great Disappointment

In 1843, as the United States went through a period of renewed religious enthusiasm, a lay Baptist preacher named William Miller announced that he'd read the Bible, run the numbers, and could tell you exactly when Jesus intended to return. Miller broke from most Christian tradition in arguing that actually, none of the prophecies in Revelation had been fulfilled yet: They would all be coming in the future, and that future would begin in 1843 ... no, wait, 1844!

Without wholly explaining his math, and despite Jesus himself announcing in the Gospels that no one would know the hour of his return, Miller announced that October 22, 1844, was when the Lord would arrive again. Oh, and sorry about that whole "1843" thing he had said last year. 100,000 or so devout optimists waited all that day and some into the following early morning, waiting for... something. What they got was cold and annoyed. Some thought Jesus had come in secret, for His own reasons, and others threw off their faith entirely. The whole affair became known as "the Great Disappointment."

Though Miller was ultimately incorrect about the time and date of the Second Coming, he still secured a legacy for himself in American religious thought. Modern groups like the Seventh-day Adventists and the Jehovah's Witnesses are "Millerite" in that they expect the events of the Book of Revelation to lie wholly in the future — but most have avoided predicting exactly when.

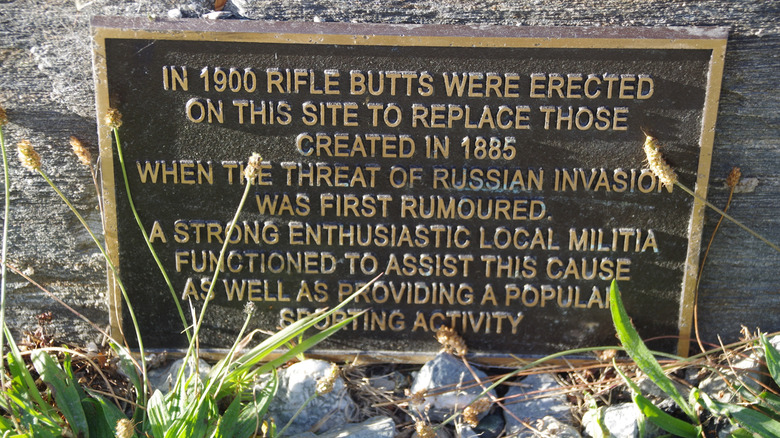

The Russian invasion of New Zealand

The people of the Caucasus, Siberia, Poland, Hungary, the former Czechoslovakia, Afghanistan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine can tell you: Threats of Russian invasion are often a very real warning you should take seriously. But they won't be calling New Zealand as an additional witness. The paradisiacal islands about a mile past the end of the world were briefly panicked about having to eat borscht and learn a new alphabet, but the czar's ambitions never extended that far south.

British forces had joined those of France and the Ottoman Empire in an alliance against Russia in the Crimean War of 1853-56, so relations were not excellent in the mid-19th century. By the 1870s, Russian ships were occasionally trawling the South Pacific, and so in 1873, an enterprising newsman tried to get New Zealanders to take the Russian threat seriously. His solution? A hoax news report that a Russian ship had entered Auckland harbor, launched a submarine, and kidnapped the mayor in an attempt to shake down the colony for ransom. (He dated the news report three months into the future in order to underline the "theoretical" nature of the report.) The initial panic was limited, but Anglo-Russian jockeying for influence in Afghanistan in the mid-1880s led to the construction of some just-in-case fortifications around New Zealand's coastal cities.

Poison comet of 1910

Halley's Comet is a regular visitor to Earth's skies, but its 1910 check-in promised to be special. The Earth would pass through the tail of the celestial object, possibly adding a bit more twinkle and pizazz to the show. Unfortunately, when Camille Flammarion, a French astronomer without modern media training, was interviewed about the upcoming event, he dared to speculate. The scientist noted that though unlikely, the comet could maybe strip the oxygen from the air or impregnate the atmosphere with fatally corrosive gases. (You know, just spitballing.)

Though Flammarion wasn't the only person to posit unlikely but lethal outcomes, his comments were among the first in a chain of partial truths and guesstimations that led some people to think the comet would doom the planet's population. When approached for a followup, Flammarion started talking about cyanide-like poisons infiltrating the atmosphere. Fatalistic readers blew off their duties — why plant crops or pay bills if we're on our way out? — and, as usual, unscrupulous actors responded with snake-oil preventatives. Some hid in caves or sealed-up rooms, and sadly, a few suicides were even attributed to comet panic.

Halley's Comet's 1910 swing ended as it always has — in a pretty cosmic display with no connected deaths by poison on Earth. (One young woman was killed in a fall from a roof, where she was watching the skies.) In 1984, Flammarion's predictions finally came true, but only within the confines of a valley girl-themed zombie flick called "Night of the Comet."

1938 War of the Worlds panic

On October 30, 1938, American airwaves were abuzz with news of an invasion. A hostile intruder had landed in New Jersey and was making short work of American defenses with new and terrible weapons. If you don't remember this war from history class, it's because it was, in fact, just a radio play. As a Halloween treat and an experiment in the power of radio drama, a young Orson Welles transferred the alien-invasion novel "War of the Worlds" from the Thames Valley to New Jersey and adapted it for the radio in the form of news broadcasts. Unfortunately, the intermittent warnings that the whole affair was fictional were not frequent or convincing enough, leading to localized panics.

Or did they? The story of the "War of the Worlds" false alarm has been built on fairly shaky evidence. Contemporary surveys indicate that not many people actually listened to the broadcast, which was competing with much more popular programming on other stations. Much of the story of the "panic" seems to have come from huffy news reports in the days after the broadcast, harrumphing at the recklessness of the endeavor and overstating the reaction. Letters to the editor responding to these same grumpy editorials report having seen no significant panic. Americans in 1938 generally knew that aliens hadn't landed — and that the coming war would be against an enemy much closer to home.

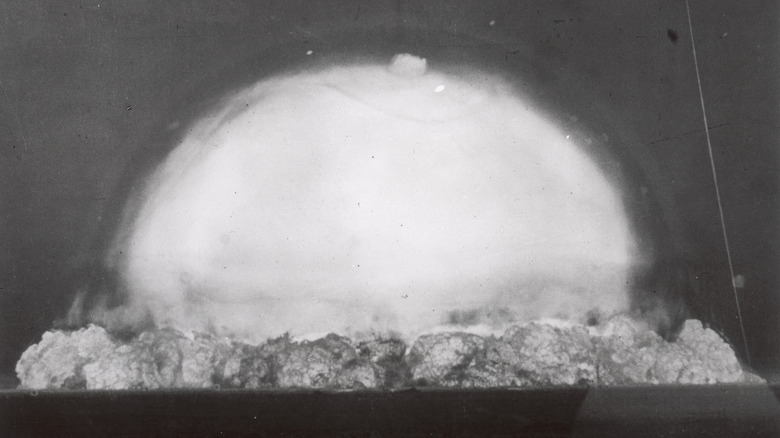

Trinity Test

The Trinity Test of a plutonium bomb on July 16, 1945, was the first atomic weapon detonation in human history, and some observers worried that it would be the last. Not because humanity would recoil and place this curse firmly back into Pandora's box, but because it would ignite the atmosphere and kill us all. Scientists feared that the nuclear test could get so hot that it would set off a self-sustaining fusion reaction with the nitrogen in the Earth's atmosphere, which would indeed have been ballgame for the human race. (For reference, nuclear fusion is the same process that powers the sun.) Robert Oppenheimer was assured by his colleagues that the odds of such an outcome were low, given the relatively low temperature and pressure of the atmosphere, so the test went ahead.

Gallows humor apparently made the rounds of the assembled scientists before the detonation. Enrico Fermi took bets on whether the bomb would eradicate all of New Mexico, and Edward Teller basted himself in sunscreen. When the test succeeded, the answer was clear: The bomb was just about the right size and strength to take out a Japanese city.

Global thermonuclear war (so far)

Fortunately for doomsayers in the generations after the Trinity Test, the continued proliferation of nuclear weapons has given the human race many more opportunities to scorch itself off the face of the earth. Washington and Moscow have both had systems ready to fire nukes at a moment's notice for decades, and the time needed to ascertain whether the other country has launched an attack may be perilously short (here's what even the smallest nuclear war would look like). And there have been plenty of false alarms that have not led to global thermonuclear war but nevertheless scared people.

In Norway, there was information about a planned research launch that didn't land on the correct desk in Russia. Radar in Greenland misindentified the moon as nuclear missiles. Test tapes were misinterpreted as actual data (which has occurred at least twice). A single switch in an AT&T phone station taking out two early-warning sites. And in the most famous incident, the 1983 close call in which the reflection of the sun on cloud tops being picked up as missiles by radar. In this last event, only a Soviet watchman's unwillingness to believe in a small American sneak attack forestalled catastrophe.

Richard Nixon's drinking has also been cited as a risk factor. As the jowly not-crook's presidency barrelled toward its ignominious end, the outgoing head of state drank heavily while clinically depressed. For this reason, any order from the president involving nuclear weapons was first to be routed through the U.S. Secretary of Defense, James Schlesinger.

Y2K

"Y2K" was shorthand for a potentially serious computer issue that was expected to cause snarls when the calendar flipped over to the year 2000. Dates stored with two-digit years might misread the new year as "1900" and miscalculate all sorts of things, leading many to speculate the most fevered scenarios. From planes falling out of the sky to a 1929-style stock market crash so fierce the market would crack the pavement when it hit, some were foretelling a catastrophe. As it turned out, there was no major upheaval, and most people were able to enjoy champagne and maybe even a tipsy kiss that New Year's.

File this one under "crisis averted." The bug was actually a serious risk — the media had not so much blown it out of proportion as it had failed to call enough attention to the enormous amount of money and work that went into Y2K-proofing computer systems worldwide. As early as 1988, people were working on the issue. Given 12 years and a hard deadline, even tech support can address a problem, and the world sailed into the new millennium with most of its old problems intact but without the added crisis of Y2K meltdowns. American monitors even detected a Russian missile launch and attributed it to glitching. Only later was it clear that they had been actual missile launches, but they were part of the Chechnya conflict.

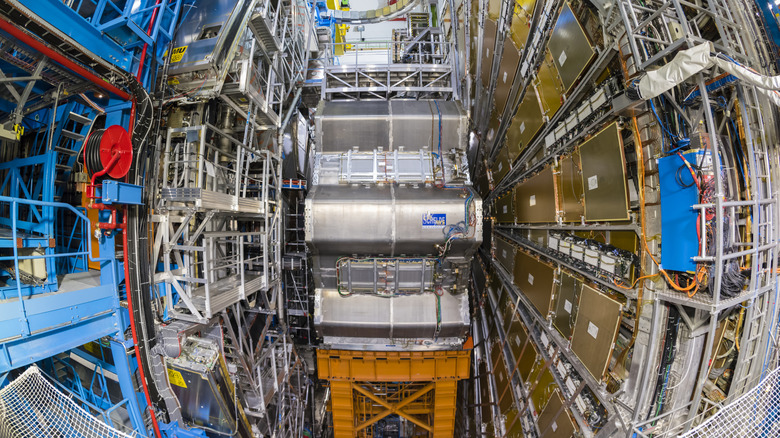

Large Hadron Collider panic

Particle accelerators advance physics research by speeding up particles as fast as they can and then slamming them into a target (which can be other fast particles), allowing scientists to look through the debris for information. The largest of these is the Large Hadron Collider, which lies below the Franco-Swiss border and is operated by CERN, which stands for European Council for Nuclear Research (but in French). Information gathered from experiments here has allowed physicists to explore (or at least look for) dark matter, additional dimensions, and the Higgs boson that creates mass.

Panic around the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) largely stems from the fear that the experiments carried out inside it could result in tiny black holes. The popular understanding of black holes as gigantic star-munching terrors is from science fiction and a misunderstanding of scale: Any tiny black holes created in an LHC-like accelerator would be not only tiny but also very very short-lived, since they evaporate through a specific kind of radiation. Theories from a bit further into left field have posited that the experiments could open a portal into another dimension. And given the unfortunate nickname of the Higgs boson, "the God particle," some people have apparently worried that the LHC could open a gate to hell.

Scientists hoping to reassure the public have noted repeatedly that cosmis rays from the sun repeatedly strike the atmosphere with more force than is generated in the LHC. All that's different in the accelerator is the presence of a controlled environment that allows data to be gathered, interpreted, and eventually released to the public whether they're paying attention or not.

Ebola transmission in the United States

From 2014 to 2016, an outbreak of the Ebola virus savaged the West African countries of Liberia, Guinea, and Sierra Leone, with isolated cases also appearing in Italy, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Nearly 30,000 people were infected, and 11,325 people died. An additional casualty of the West African Ebola outbreak was rational behavior among people in the United States. Ebola is very deadly if you are unlucky enough to catch it, but it's not particularly contagious as viruses go. It's not airborne, and it's generally not transmissible before symptoms appear. But the American public, when polled, largely believed that both of these transmission scenarios were possible. Politicians, never willing to miss an opportunity, began to question CDC guidelines for exposure and quarantine, with a number of state governors going rogue and adopting their own, hard-to-enforce rules for returning health care workers.

All in all, the United States saw a total of 11 Ebola cases. Only two of these patients died, and both had contracted the disease abroad before coming to the U.S. Proven locally transmitted cases were limited to two nurses, both of whom lived. Additionally, serious concerns about Texas' quarantine policies were raised by the ACLU, which reported that the family of one of the fatalities were forced to remain in a small apartment with the dying man and soiled bedding, putting them at an unacceptable level of risk.

Nibiru/Planet X

Gravitational wobbles in the orbits of bodies on the edge of the solar system hint that there may be an undicovered planet way, way out there. This ninth planet (or tenth, for #JusticeForPluto bitter-enders) would probably be several times Earth's size and much, much more distant than Neptune, taking over 10,000 Earth years to complete a single orbit. The existence of such a body would help answer some confusing questions about the solar system, largely having to do with why some orbits are "tilted" compared to others. But as yet, Planet Nine (or Planet X, if you're feeling dramatic), has yet to be discovered.

Discovered by science, that is: As early as 1976, pseudoscience fans were reading a book called "The 12th Planet," which argued for the existence of an, er, 12th planet named "Nibiru," the home world of the aliens who directed human evolution, that came around every 3600 years. This fictional planet went on to have a rich life in other conspiracy theories, which generally center on its eventual collision with the Earth. Nibiru was supposed to hit in 2003, then in 2011, then in 2012, but no dice, and the theory of a sneaky rogue planet isn't even scientifically credible. A large planet whipping around at the necessary velocity to make all the conspiratorial numbers jive would be easily detectable from its gravitational pulls on other objects and would be straight-up naked-eye visible for years on either side of its close approaches.