The Taiping Rebellion: The Deadliest Civil War You've Never Heard Of

It's pop quiz time. What's the second deadliest conflict in human history? Without a doubt, World War II takes the top spot, ending an absolute minimum of 60 million lives and most likely several tens of millions more (via the National World War II Museum). But what planet-engulfing conflict could possibly hold second place? If you're thinking World War I or the Mongol Conquests, prepare to be shocked. Although precise death tolls are hard to measure, the conflict that's most likely killed more than nearly any other in history wasn't some global dust-up or even a continent-wide royal rumble. It all took place in a single country: China. It's name was the Taiping Rebellion, and it claimed anywhere from 20 million to a jaw-dropping 70 million lives (via History).

The deadliest civil war in human history, the Taiping Rebellion broke out in the middle of the 19th century. What started as a small sect of violent Christians quickly transformed into a rampaging army of more than 2 million. At its height, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom controlled most of southern China from its Nanjing capital. Ruthless and brutal, its leaders envisioned an apocalyptic end times battle consuming the nation, and they sure delivered. Your history books likely taught you that the US Civil War was bad. Buddy, it ain't got nothin' on the Taiping Rebellion.

The set-up for the Taiping Rebellion

In 1814, history's deadliest religious leader was born. Hong Xiuquan (pictured) was the guy who'd inspire the Taipings to rebel and plunge China into chaos so great, it was chaotic even by ancient Chinese standards. (It was a very crazy time period.) But Hong wasn't born an arch-manipulator. Nah, he just had the fortune to be born into a society all but ready for a spectacular collapse.

As Britannica explains, China in 1814 was under the Qing dynasty, a group of ethnic Manchus who'd conquered the Han Chinese back in the 17th century. Although they'd initially been dynamic rulers, they were by now about as dynamic as Elmer Fudd. There'd been no infrastructure improvements to China for 100 years, even as the population tripled. On top of that, the rigid Confucian code sorted people into classes they couldn't escape from. The result? A whole bunch of angry people trapped in miserable poverty, with no hope of bettering themselves. Wow. That, uh, sure sounds like a recipe for a harmonious society!

Things were even worse for the Hakka class, of which Hong Xiuquan was a member. A group of internal migrants who'd fled the Mongol invasions back in the 13th century, the Hakka were still treated as outsiders (via Britannica) and all sorts of ready to give their Qing overlords a kicking. Spoiler alert: They would soon get the chance.

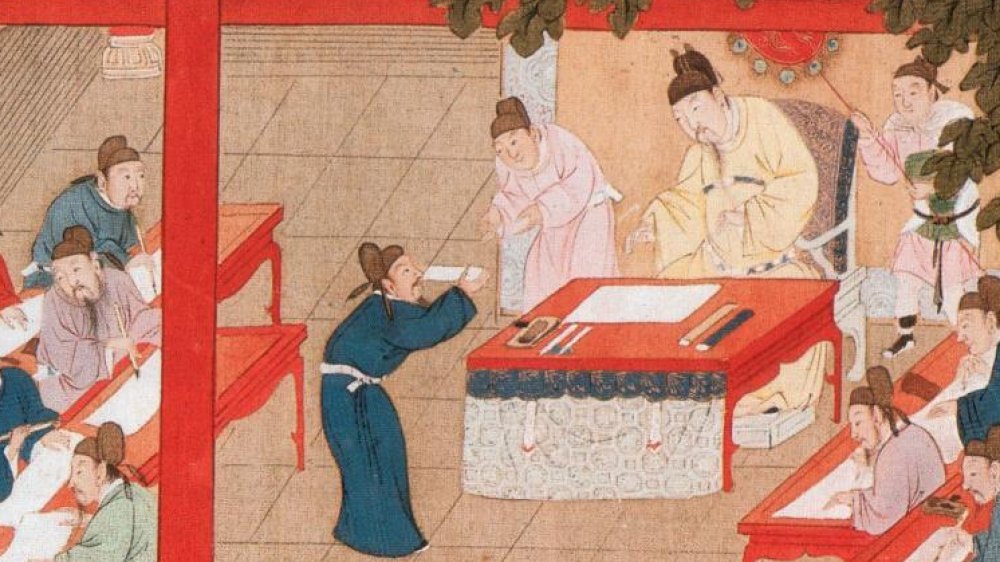

The soul-destroying exam

You know how in the Matrix trilogy the machines deliberately created an escape valve in their simulation so the most desperate humans could blow off steam by leaving for Zion? Oh, you wiped the sequels from your memory? Well, if you hadn't, that would've been a perfect analogy for society under the Qing. Although most people were stuck in their crappy lives, an exit did exist. The Imperial Exam could be taken by almost anyone, and passing it meant not just money for you but for your entire village. There was just one catch. The pass rate was a dismal one percent.

According to BBC's In Our Time, the Imperial Exam was almost a religion in Hong Xiuquan's time, a way to bring both honor and money on your entire village. But it was also widely hated. There are contemporary poems about men driving themselves mad trying to pass. Still, though, people kept on trying — people like Hong Xiuquan.

As Britannica describes, Hong's community recognized from an early age that he was intelligent and therefore their quickest route to ker-ching. They banded together to pay for his tuition and basically bet their life savings on this one poor Hakka kid passing. It doubtless exerted tremendous pressure on the young boy's mind. This would turn out to be something of a mistake.

The Taiping Rebellion gets started with some apocalyptic dreams

By 1837, Hong Xiuquan had become an acknowledged master ... at failing the Imperial Exam. Seriously, the guy took it three times, and each time he failed. But if any Qing exam-takers had been able to see the future, they might've passed the poor guy regardless. Like Hitler getting rejected from art school, Hong didn't take being failed lightly. But while Hitler reacted by channeling his inner ultra-racist, Hong's path to genocide was much weirder.

After failing his third exam, Hong was confined to bed, during which time he was wracked with visions. These were pure, A-grade Alice in Wonderland fever dreams. The BBC describes how Hong went into the sky and met a great man with a long beard who told him to slay all the demons on Earth. Britannica describes him also meeting a middle-aged man who instructed Hong in the art of kicking demon backside. By the time Hong awoke, days had passed.

Five years later, Hong had just failed the Imperial Exam for a fourth time when a cousin gave him a pamphlet on Christianity. Reading it, Hong realized the old man in his vision had been God and the middle-aged man was Jesus. Hong also realized that he was Jesus' Chinese brother, put on Earth to exterminate all demons ... starting with the Qing.

The First Opium War screws everything up

Right after Hong started dreaming about Chinese Jesus, something happened that would break the last bonds holding his nation together. Yeah, we're talking about the First Opium War. In a nutshell, British merchants (mainly the East India Company) annoyed that China wouldn't buy their goods had begun smuggling opium into the Middle Kingdom. When the Qing found out, they'd confiscated and burned the opium. Long story short, the British Empire went ahead and did what the British Empire always did and annexed as much Chinese territory as possible.

As the National Army Museum tells it, the First Opium War was basically an extended exercise in Britain kicking the Qing in the testicles, running away to laugh, then running right back up and kicking again. The Royal Navy wiped the floor with the Qing, seriously damaging their prestige. Know what else the war damaged? The whole of Chinese society. Aside from netting Hong Kong, the British won the right to flood the nation with opium, making the addiction crisis even worse.

But there was another side effect to the Opium War. The 1842 peace treaty made it easier for Protestant missionaries to enter the nation. Suddenly, a whole bunch of Chinese peasants were aware of Christianity in a way they'd never been before. Now all it would take was one charismatic preacher to capitalize on this, and he'd have a religious army ready to roll.

The civil war kicks off with a literal million man march

Despite the influx of Christianity, most people initially treated Hong's preaching exactly how you'd probably treat a guy telling you he was Jesus' brother. But his teachings did find a solid audience among his fellow Hakka. Poor, fed-up, and done with this whole "being oppressed" thing, they formed a militia loyal to Hong known as the God Worshippers. And this was a militia that knew how to fight.

As Facing History describes, by 1850, Hong was preaching a message of economic opportunity that resonated with Imperial China's poor and downtrodden. Inside this message was a not-so-secret call to arms. History tells how Hong was offering free land to potential followers and a kind of proto-Communism to live under, both of which would pretty clearly involve overthrowing the Qing. Eventually, the Qing realized this and sent soldiers to deal with the God Worshippers. It's at this point that lā shǐ really hit the diàoshàn.

When the Qing armies faced the militia, they just fell apart. Amazed, Hong and his guys decided to press their advantage. They pressed it all the way up the Yangtze River, gathering more followers until some 2 million were marching behind Hong. In 1853, this gigantic army reached the former imperial capital of Nanjing and overran it. From a Hakka nobody, Hong was suddenly in charge of southern China.

The Heavenly Kingdom has a serious naming problem

Once in Nanjing, Hong declared the creation of the "Taiping Tianguo," aka the Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace, which was built on Christian principles. Well, that was the idea. The reality was more Hong taking all the craziest fire and brimstone parts of the Old Testament and jettisoning all the "turn the other cheek" stuff. As History lists, the number of capital crimes in the "Heavenly" Kingdom was insane. You could be beheaded for singing raunchy songs, for smoking opium, for "casting amorous glances," and for having lustful thoughts. Man, take out the opium, and that's like half our checklist for a regular day. But Hong went even further. According to Britannica, he made it an offense for even married couples to have sexual intercourse. Oh, plus he had himself a solid gold throne made (above).

At the same time, the new kingdom indulged in flat-out wackiness. The New York Times describes how Hong and his lieutenants would decide state policy in religious trances, then have their proclamations issued as poems that gangs of women were forced to memorize and sing in public. But even this weirdness couldn't hide the Taipings' brutality. Public torture and executions were part of daily life in the Heavenly capital, and the regular purges defied all reason. One "king" who displeased Hong had his entire extended family butchered and his head paraded around on a pole.

The West fails to pick sides during the Taiping Rebellion

Everyone reading this grew up in the age of Western intervention. So when word hit Europe and America that a gang of religious nutjobs were forcing a mad medieval belief system onto millions of people, what do you think happened? Ha, no, Washington D.C. and London didn't rush to liberate the Taipings' subjects. Instead, they kind of shuffled their feet and basically muttered, "Well, I dunno, maybe these religious weirdos have a point?"

In the U.S., the Christian nature of the Heavenly Kingdom — in spite of its heretical belief that Hong Xiuquan was literally related to Jesus — became a cause célèbre. The book Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom (via The Washington Post) describes how American Christians began agitating for their government to support the Taipings, with The New York Times even writing editorials in Hong's favor.

Over in Europe, it was less the Christianity and more the radical nature of Taiping society that people warmed to. Karl Marx and the continent's hardline liberals all saw Hong's devotion to land rights and economic equality as, like, the very thing they'd been agitating for for decades. Even the British, who relied on a stable China to keep buying their opium, basically shrugged their shoulders and let Hong get on with it. Had things turned out differently, it's possible the Taipings might've become recognized as China's legitimate rulers.

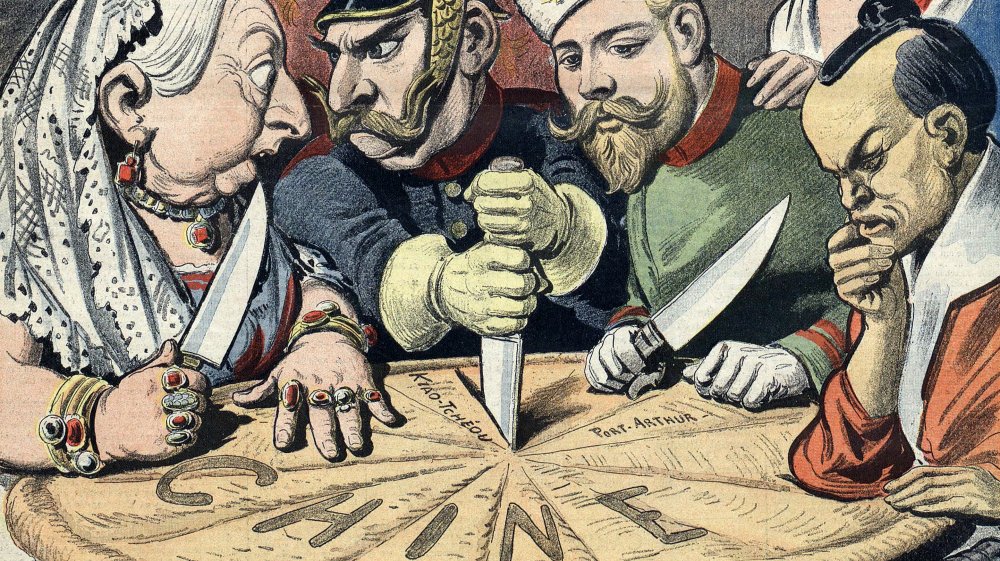

The Second Opium War screws things up even worse

Now might be a good time to ask where the Qing were in all this. Like, why weren't they busy fighting the hardline religious insurrection in their midst? Because they were too busy fighting the Europeans, of course! With remarkable bad timing, the Second Opium War kicked off in 1856, while the Taipings were still rampaging across southern China and slaughtering thousands. And so the Imperial Qing army found itself not going toe-to-toe with Hong and his goon squad but with France and (you guessed it) Great Britain.

As Britannica describes, the Second Opium War was even more nakedly self-serving than the first. Seeing the Qing tied up fighting the deadliest civil war in human history, London decided now was the perfect time to nab some prime Chinese real estate. ThoughtCo. further explains that the murder of a French priest convinced Paris to join the fray, leading to another great European carve-up of Chinese territory.

In the end, the Second Opium War only ended in 1860, after killing tens of thousands and hobbling China just when it needed all its resources to take on the Taipings. Nice work, France and Britain.

Britain gets involved in the civil war thanks to cotton

If you've been paying attention to the dates, you might've thought to yourself, "Hey, all this is happening just before the U.S. Civil War." Well done for noticing, champ! Barely had the ink dried on the treaty ending the Second Opium War than the U.S. was careering toward its own civil conflict in April 1861. And that's important to the history of the Taiping Rebellion because the U.S. Civil War had the small side effect of crashing Britain's cotton market.

In the 19th century, northern England had placed itself firmly at the center of a textiles trade that started in the Deep South's cotton plantations and ended with the Chinese buying British cloth. As the book Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom shows, the Taiping Rebellion badly dented that market. When the U.S. Civil War also exploded, London was suddenly facing down the barrel of serious civil disorder in Britain's now-penniless northern cities. Not wanting a rebellion of their own, the British were left with two options: interfere in the US Civil War or interfere in China.

You already know which one they went for. After briefly flirting with the idea of getting involved with the Confederacy, the British realized what a stupid idea that was, and they instead decided to intervene in China. And so Queen Victoria v. Abraham Lincoln: From Battlefield to Bedroom must sadly remain the preserve of historical fan fiction. Sigh.

The good guys are just as murderous as the Taipings

When the British began clandestinely training and arming the Qing, China-watchers must've hoped that the insane bloodshed of the Taiping Rebellion was nearly over. Nope. By the early 1860s, the Qing were through with the rules of war. The Taiping wackos wanted to fight dirty? Fine. The Qing would give them the dirtiest war in history.

The Qing approach was two-fold. One, as Facing History describes, Beijing allowed warlords to raise massive armies provided they use them to fight the Taipings. These "new armies" were as efficient and as brutal as warlords tend to be. The second approach was to use British (and occasionally American) warfare techniques to systematically exterminate the Taipings. The Cambridge Research blogs tells how the Qing set up vast sieges of cities across all 18 provinces with a Taiping presence, cutting them off so effectively and for so long that the inhabitants were forced to resort to cannibalism. But that was just the start. Once the starved cities surrendered, the Qing mass executed everyone inside.

The most notorious massacre was at Anqing (pictured). After a two-year siege, the Taipings surrendered, only for the Qing to chop the heads off every single male inside its walls. The women — about 10,000 in all — were carried off as "war booty." And stuff like this happened again and again. According to ThoughtCo., 600 whole cities were completely annihilated in the course of the war.

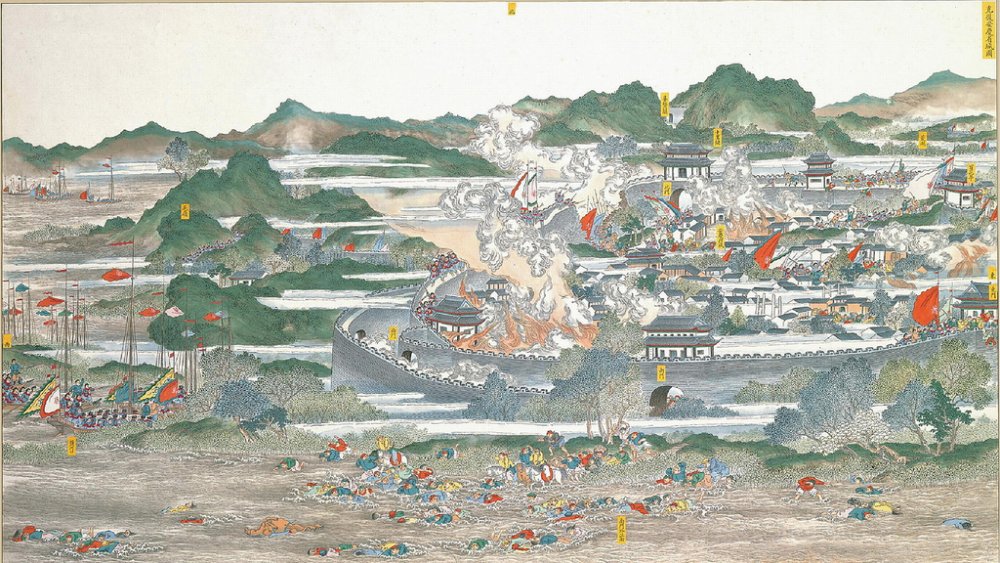

The Fall of Nanjing was super messed up

By 1864, the Qing had chased the Taipings all the way back into their Heavenly capital and laid siege to Nanjing. When the city finally fell, it would be the end of Hong and his Heavenly Kingdom, and both the Qing and the Taipings knew it. All of which might explain why the eventual conquest of Nanjing was so unbelievably bloody. Next to it, the nearly contemporaneous Battle of Gettysburg was like a teddy bears' picnic.

According to the BBC's In Our Time, Hong Xiuquan himself died in the middle stages of the siege, possibly after eating some poisonous berries, possibly while believing they were manna from God. But the real horrors came when the Qing finally breached the city walls. Over the next three days, they effectively razed Nanjing to the ground. By the time the dust had settled, it's thought 100,000 people had been killed.

The Taipings didn't go quietly. The New York Times describes how groups of fanatical true believers gathered in the last hours of the city and set themselves on fire rather than be captured. Men, women, and children all died in an inferno of blood. It's entirely possible that this was history's deadliest battle prior to World War I. By way of comparison, Gettysburg killed 7,058 (via History Net). In China, everything is bigger.

The Taiping Rebellion was absolutely devastating

Although pockets of resistance would keep fighting for another two years, the fall of Nanjing and the death of Hong effectively ended the Taiping Rebellion. The Qing regained control of China, and the Middle Kingdom enjoyed its last decades of stability before the 20th century blew everything up again. So now might be a good point to take stock of just how insane the Taiping Rebellion really was.

Today, this mostly forgotten civil war is generally estimated to have killed between 20 and 30 million people (via ThoughtCo.). To put that in perspective, that's up to 30 times the number killed in the U.S. Civil War. World War I — a war fought with machine guns, heavy artillery, tanks, and poison gas — killed only around 20 million (via Britannica). And these are just the generally accepted estimates. At the higher end, History notes that 70 million may have died in the Taiping Rebellion. Were a war to kill 70 million today, it'd still be almost one percent of the entire global population. In the world of 1860 (with the population at roughly 1.2 billion), it would've been over five percent.

And the deaths didn't stop there! The book Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom argues that Chairman Mao's Communist revolution was made possible by the failure of the Taipings. The result? The Chinese Civil War and one of the deadliest dictatorships in history. Hong Xiuquan may have died in 1864, but his memory was still killing millions over a century later.