The Real Reason The Second Wave Of The 1918 Flu Pandemic Was So Deadly

Medical historian Joseph Waring called the 1918 flu "the greatest medical holocaust in history," according to the Spokesman-Review. Between 1918 and 1919, the illness infected an estimated 500 million people, roughly one third of the world's population, per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The flu proved deadlier than WWI, killing at least 50 million people, compared to an estimated 7 million civilians and 9 million soldiers killed by the conflict. Some estimates of the pandemic's death toll top 100 million people.

This pathogenic juggernaut swept the world in three waves, the first of which occurred in the spring of 1918. According to the National Academy of Sciences, the initial bout proved so mild that some physicians concluded it wasn't actually influenza. Then came the second wave, which caused the overwhelming majority of mortalities. Death rates were all over the place, and isolated populations suffered the worst. The NAS writes that "in the Fiji islands, it killed 14 percent of the entire population in 16 days. In Labrador and Alaska, it killed at least one-third of the entire native population." What changed? How did the flu pandemic's second wave become an ocean of death?

Nations were ill-equipped to fight the flu and ill-inclined to tell the truth

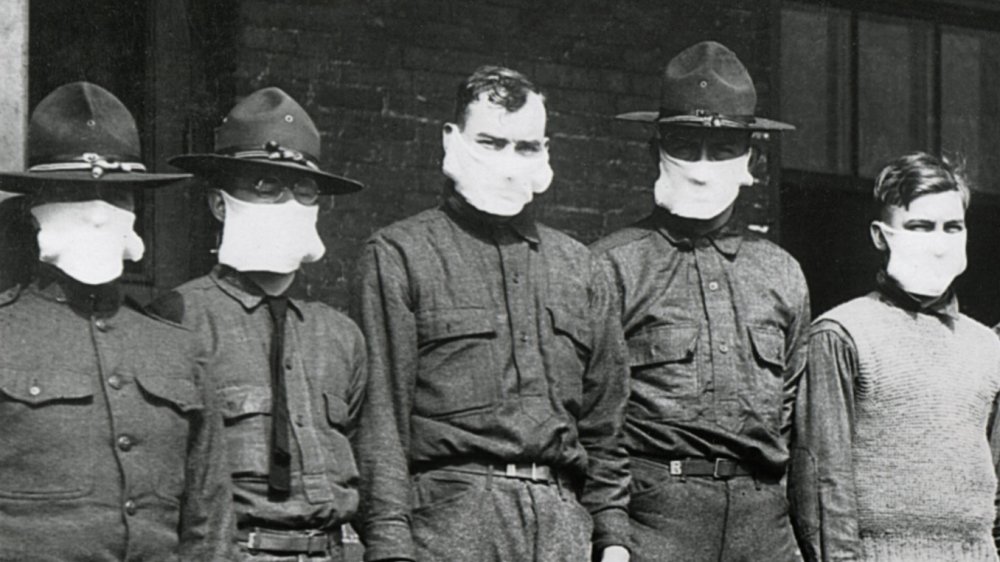

Back in 1918, the world was ill-equipped to combat a flu pandemic, and military combat exacerbated matters. The first modern flu vaccine didn't exist until 1938, according to Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health, and the National Academy of Sciences notes that the 1919 strain of the flu had highly unusual symptoms, causing doctors to misdiagnose it as dengue, cholera, or typhoid. Meanwhile, WWI turned the world into a pathogenic powder keg.

In an interview with PBS NewsHour, author Kenneth Davis argued, "Because military men were sent overseas, or sailors were sent from one port to another, the flu quickly spread across the U.S," where 675,000 Americans died of the virus. In his book, More Deadly Than War, Davis also asserts that a massive influx of refugees in cities, poor nutrition, and a dearth of nurses, doctors, and medications all contributed to the lethality of the pandemic.

Warring nations worsened the situation by hiding information about the less severe first wave of influenza, the rationale being that divulging the truth would ruin morale about the war. The U.S. even passed legislation outlawing speech that disparaged the federal government. So officials simply downplayed outbreaks, essentially telling people not to sweat it. That misinformation helped spread illness and devastation on a historic scale.