Life Under Communist Rule Was Worse Than You Think

Like all political ideologies, communism promises a lot of things: progress, equality, and a generalized idea of "fairness" in which everyone will get what they need. And like all political ideologies, communism delivers on its utopian promises intermittently at best, more frequently delivering to those living under communist governments shortages, tyranny, and vast expanses of gray cement. In the century since the Russian Revolution brought about the first true, large-scale experiment in communist governance, far-left governments have popped up around the world and, in the worst scenarios, proven themselves every bit as capable of brutality as their right-wing ideological enemies. The words were different, but not the tune.

In their struggles to gain and keep power and their attempts to create perfect societies, communist governments committed some of the 20th century's most shocking atrocities. The echoes of these cruel policies continue into the present, even as the next generation of allegedly egalitarian dictators ruins lives and countries with false promises of a perfect world just around the corner.

If you tried to cross the Berlin Wall, they would kill you

East Germany didn't want people to leave, but many people did so anyway. The gap in quality of life between the Soviet-created East Germany and the rest of the country was fairly apparent, especially in Berlin, where, during the Cold War, most of the city existed as an island of relative freedom surrounded by the East. So many people fled west that East Germany was facing a population crunch and brain drain, and so the communist government responded with lethally strict border controls and, in 1961, the construction of the Berlin Wall, surrounding West Berlin and sealing it off from would-be immigrants from "the other Germany."

The Berlin Wall stood until 1989, and escapes over, through, and around it became the stuff of legend. Failures to escape, though, served as grave cautionary tales because the East German guards would shoot to kill. During the 28 years the wall stood, at least 140 people died on or around it, a number that includes would-be escapees, border guards killed in attempts to get out of the East, and a handful of unlucky bystanders. With the addition of people who died crossing the border at official checkpoints, people who were killed trying to cross the border at other places than in Berlin, and those who drowned in the Baltic Sea trying to swim around the fortifications, the total dead at the border between the Germanies is an estimated 650, per The Berlin Wall Foundation (Stiftung Berlinger Mauer).

Science became a matter of faith

If you think science is a matter of objective truth, then you wouldn't have made a very good Soviet scientist. This is an exaggeration, but barely. In the early Soviet state, political bona fides could easily trump actual scientific knowledge and ability, and nowhere is this misprioritization more evident than in the career of Trofim Denisovich Lysenko. Lysenko was an unimpressive scientist, but he was from a poor Ukrainian family — exactly the sort of anti-elite bona fide Stalin was looking for as he built the Soviet state.

"Lysenkoism" now means "government misuse of science with a political goal," but initially it referred to a new model of genetics and inheritance that Lysenko was instrumental in developing. He thought "genes" sounded too mystical, and so he argued against them. And for political reasons, this became the official Soviet line on biological inheritance.

If this does not immediately sound like a problem — silly, but not dangerous — know that this whole debate took place in the context of trying to improve agricultural yields. Lysenko was promoting understandings of plant biology that simply weren't relevant to the pressing problems of creating enough food to feed growing populations in the Soviet Union and its allies. Chinese adoption of Lysenkoist ideas of plant biology were a contributing factor to the terrible famine of 1959-1961.

Famines

Inefficient distribution systems and adherence to scientifically dubious but politically valuable techniques would be enough to create a famine, but communist regimes haven't stopped there. Layering these grave issues with callous political decisions about who deserves to eat, communist regimes have presided over and even engineered some of the worst starvation crises of the 20th century.

The Holodomor in famously fertile Ukraine was a Stalinist project meant to starve independence-minded Ukrainians into submission, with some 4 million Ukrainians dying in the wake of confiscations of food and blockades of villages that had allegedly failed to meet production quotas of grain. An imprudent attempt to jump-start Chinese industrialization with homemade iron production pulled farmers away from their fields and led to the Great Chinese Famine, which killed at the very least 15 million people from 1959 to 1961 — though Ebsco says estimates range as high as 50 million. An Ethiopian attempt to replicate Stalin's "successes" by forcing people to move into planned collective villages disrupted food production and killed over 400,000 people in the mid-1980s.

Perennially unhappy North Korea was hit by a perfect storm of governmental mismanagement, natural disaster, and land exhaustion in the mid-1990s. In another classic play from the communist governance manual, aid meant to save starving citizens was instead diverted for military use. One to 2 million people died, with malnutrition lasting several years after the formal end of the famine in 1998.

The Soviets crushed attempts by their satellites to break away

After its successful invasion of Eastern and Central Europe during World War II, the Soviet Union intended to play for keeps, setting up a communist puppet government in every country it had "liberated" except lucky little Austria. When the United States and its European allies established the NATO alliance in 1955, the Soviets replied with the Warsaw Pact, an alliance of all these communist, Soviet-supported governments that served as both a counterweight to NATO and a check on any of these countries getting any big ideas about making its own decisions.

Hungary tried to break away from Soviet domination in 1956, hoping that Stalin's death would create an opening to slip out of the Soviet sphere, but Soviet troops immediately crushed the new Hungarian government. Same song, next verse in Czechoslovakia in 1968: a reformist government was overthrown by Soviet forces with help from the Warsaw Pact nations. In 1981, the Soviet-aligned Polish government imposed martial law to avoid unrest and potential reform before Moscow could intervene, having learned from the unhappy examples of its neighbors. The Warsaw Pact remained in force until 1991, by which point all its members had overthrown their communist governments and the Soviet Union was on the verge of breaking up into its constituent republics.

The Khmer Rouge genocide

In 1975, when the Khmer Rouge communist forces, in a strange alliance with a deposed king, captured the capital of Cambodia, observers knew huge changes would arrive in the Southeast Asian country, but few predicted how horrific the new government would be. Until it was deposed by an invasion from war-weary but horrified neighbor Vietnam in 1979, the Khmer Rouge presided over a bloody reorganization of society now widely recognized as a genocide. The violence claimed between 1.5 and 3 million lives; the chaos makes any statistics hard to trust, but the population in 1970 was probably just over 7 million.

Pol Pot, the new dictator of Cambodia, presided over the expulsion of town and city dwellers into the countryside to work as farmers despite having no experience and limited equipment, with families split up to reassign individuals to forced labor brigades. The Khmer Rouge distrusted intellectuals, which was defined broadly as nearly anyone working in a profession, and even people simply wearing glasses could become targets for violence and murder. Ethnic groups were also particularly targeted, with Chinese and Vietnamese populations decimated and some 70% of the Muslim Cham minority dying at the regime's hands. Most notoriously, those deemed unworthy of life by the regime were taken to rural "killing fields" to be slaughtered en masse after digging their own shallow graves.

Cuba put queer people in forced labor camps

After the Cuban Revolution, the new government under Fidel Castro did as revolutionary governments often do: It turned on Cuban society in order to identify various groups that would be punished and marginalized rather than offered a place in the new Cuba. One of these groups was LGBTQ Cubans. Castro described homosexuality as a "bourgeois perversion," and so queer Cubans were forced into labor camps by the new government along with priests, religious minorities, dissidents, and other enemies of the new regime. While these camps only operated from 1965 to 1968, the identification of queer Cubans as a risk to society lasted longer.

The Cuban government treated homosexuality as a danger that might spread, educating "gay-seeming" boys separately from their peers and criminalizing homosexual activity. (The law against homosexuality was softened in 1988 to only outlaw "manifestations of homosexuality in public," but still carried months of potential prison time.) A 1971 law prevented gay Cubans from working in any job that would put them into contact with young people. In 1986, HIV-positive Cubans were ordered into perpetual quarantine, a policy relaxed in 1993 to allow for weekend visits home and employment. It was repealed later that year and replaced with a strict and invasive monitoring system.

Contraception and abortion were outlawed in Romania under Decree 770

In 1966, Romania's dictator Nicolae Ceausescu had what he apparently thought was a great idea. In order to increase Romania's population and create more good socialist workers, his government issued Decree 770, which banned abortion and contraception. This last point was academic: Contraception was not widely available, but abortion was, and Romanian women used it to limit their family sizes to what they could manage in far-from-thriving socialist Romania. Ceausescu didn't care what Romanian women wanted or could manage, and Decree 770 lasted until 1989, when Ceaucescu was the only European communist dictator to face trial and execution for his actions in office.

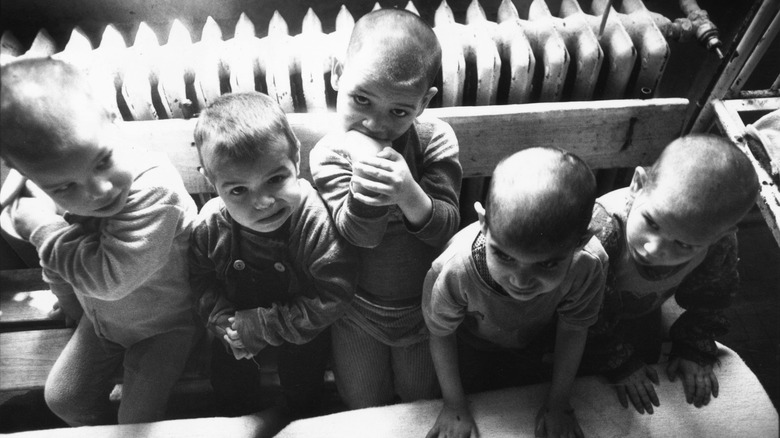

Right after Decree 770 was implemented, there was a baby boom — but it was short-lived, creating an unmanageably high cohort of 1967 births, and then the birth rate began to tumble again. At the same time, maternal mortality shot up, in part because women who died from unregulated abortion were counted within these statistics. Ten thousand women and girls died from such procedures, per Human Rights Watch. Compounding the crisis, children born to families who could not support them filled orphanages, which became notorious for their poor conditions, abusive staff, and high death rates, especially in those for disabled children.

China's Cultural Revolution

The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution — the Cultural Revolution, for short — was a decade of bloody chaos in China resulting from Mao Zedong's plan to weaponize the Chinese public against domestic enemies. These domestic enemies, of course, were largely people Mao disagreed with on the future of the state, and he threw away at least 500,000, and maybe as many as 2 million Chinese lives to consolidate his control, according to The Guardian.

In 1966, Mao's government recruited young people into units of "Red Guards," poorly controlled paramilitary organizations with a brief to persecute anyone who wasn't revolutionary enough and act against the Four Olds: old ideas, old customs, old habits, and old culture. (Mao, 72 in the summer of 1966, was also an "old," but the irony seems to have escaped him.) The British Embassy was sacked and burned by a mob in 1967. In 1968, when unorganized violence continued with victims chosen for "crimes" as trivial as allegedly bourgeois haircuts, Mao sent the rowdy urban youth into the countryside for reeducation by peasants, then ordered the army into the cities to restore order. By 1971, the country seemed closer to normal.

In addition to murders and harassment, people denounced as anti-revolutionary were tortured by the Red Guards, Mao's unofficial student-led paramilitary. Alleged separatists in Inner Mongolia reportedly ate the flesh of their victims in Guangxi. Nevertheless, the army was responsible for most of the deaths during their campaign to reassert central control, with perhaps 2 million people dying in the disruptions — along with many cats, as pets were seen as Western-style decadence.

Gulags

After the Bolsheviks took power in Russia in late 1917, Trotsky and Lenin cemented control in part by creating a new kind of enemy: the class traitor. This extremely flexible label could be applied to anyone the government wanted to punish or suppress, and one of the primary means of punishing such people was imprisonment in a gulag.

Gulag is an acronym for the Russian for Main Camp Administration, a division of the ministry of the interior that ran these punitive labor camps. People who had in some way displeased the Russian or, later, Soviet government would be sent to these harsh camps, most of which were in Siberia or far Northern Russia. These camps were later combined with common prisons in order to streamline operations and provide more forced labor for development projects like mining or infrastructure development. The Soviet economy came in part to rely on the effective slave labor of those in the gulags, providing an obvious incentive to send more people.

Some 20 million people were sent to gulags while they operated, of whom Ebsco reported an estimated 1.6 to 15 million may have died from the difficult conditions of transport to the camps, overwork, abuse, and cold. The formal gulag system was abolished in 1957 (the Soviet economy had developed and didn't need quite so many slaves), but the modern Russian state continues to make use of penal colonies that are the apparent heirs of the gulags.

China's 1-Child Policy

Populous China promoted family planning beginning with the arrival of the communist government in 1949, but despite these efforts (and the terrible famine of 1959-1961), the population of China was creeping towards 1 billion by the late 1970s. Dictatorships being what they are, the Chinese government decided to enforce what it had previously suggested, and in 1980 established the one-child policy. With the exceptions of some ethnic minorities and couples whose firstborn had a disability, Chinese couples were limited to a single child.

Authorities offered carrots and sticks: Free contraceptives and financial incentives for those who obeyed, and economic or social punishments against the rebelliously fertile. In the worst cases, women were subjected to forced sterilization or abortions to enforce the little-sibling ban. There were workarounds for rural families or parents who were only children themselves, but the policy in general was a heavy-handed intrusion into family planning and composition. China changed the policy to allow two children as of 2015 and three in 2021.

Communism hadn't eradicated Chinese patriarchy, and many couples vastly preferred their one permitted child to be a son, even to the extent of aborting, killing, or abandoning unwanted daughters. The ratio between the sexes remains skewed in China today, with significantly more males than females and a shortage of young to middle-aged women.

Ethiopia's Red Terror

In 1974, when the emperor of Ethiopia and his government were overthrown by the Derg, (or Durgue), a Marxist militia, some people hoped that the authoritarian rule of the spendthrift old monarch would be replaced by something better. These people were incorrect because the Derg, hoping to ensure its hold on the country, scoured Ethiopia with a campaign of violence and repression equal to or worse than those enacted by their fellow travelers in Europe and Asia.

Ethiopia's Red Terror lasted from 1976 to 1978 and killed tens of thousands of people, with exact figures murky. It started as a power struggle between competing Marxist groups, snowballing into a much graver scenario after Mengistu Haile Mariam took power in 1976. Mengistu deputized militias and neighborhood groups to kill members of the rival faction and, hey, any other potential enemies of the Derg they might come across. The pogroms started in Addis Ababa and spread to Ethiopia's cities, with the bodies of those killed left in the street; a particular cruelty was that anyone claiming a body or even checking its identity was likely to become a victim as well.

The violence slackened in 1978, though Mengistu remained in power until his 1991 overthrow. He was convicted of genocide in 2007 by an Ethiopian court and sentenced to death, but the 88-year-old remains in exile in Zimbabwe at the time of this writing.

Millions of Venezuelans have been forced to leave

In late 2024, Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro declared himself the winner of the country's election — a reality that had little to do with the votes cast and everything to do with his desire to continue choking the life out of the struggling country. To be fair, he won his first election in 2013, running as the designated successor of cancer-stricken Hugo Chavez, who died of the disease, but that was the last time Maduro was interested in playing fair.

During what can only with generosity be called Maduro's "leadership," the economy of once-wealthy Venezuela has collapsed to a degree numbers struggle to capture. Inflation peaked at 9,500% in 2019, and the monthly minimum wage is now a fraction of its former purchasing power at about $3. In reaction to this economic hollowing out and the other cruelties of the regime, including the abduction, imprisonment, and torture of real and imagined opponents, Venezuelans have voted the only way they effectively can: with their feet. Between 7 and 8 million Venezuelans have left the country during Maduro's tenure, compared to a population of about 30 million still in the country in 2022, meaning somewhere between a fifth and a quarter of Venezuelans have chosen migration and exile over more Madurismo.