People Who Knew A Pandemic Was Coming Before It Happened

Okay folks, don't panic. It's a pandemic, sure, but it's not like it's the zombie apocalypse or anything. There's no need to loot the grocery stores or find some abandoned prison to live in, just stay in your house for a couple of months, okay? You might want to get a bullet-proof fire safe for your toilet paper, but other than that, just chill.

COVID-19 is dangerous, and it's up to all of us to do what we can to stop its spread. But take comfort in knowing that here in 2020, we have the benefit of understanding the thing we are fighting and knowing how to protect ourselves from it. In theory, anyway. Not so many years ago, things were different. Epidemics were caused by a terrifying, invisible enemy, and they seemed to appear with no warning and often ended in exactly the same way. But almost always, even hundreds of years ago, there were people who had a hunch that something bad was coming. And if only everyone else had listened, then history might not have taken so many grim turns.

Bill Gates saw a pandemic coming

Today, we have the benefit of thousands of years of medical history. We can observe massive amounts of data that give us information about the way that viruses spread, how they might mutate, what symptoms they cause, and how many people they kill. Knowing what we know about viruses and other agents of disease, we can see epidemics coming from miles away. So wait, why did no one see COVID-19 coming? Well, actually, they did. But those of us who were actually paying attention mostly just went, "What? No way dude. Shut up while I go tho this bar and let a bunch of strangers breathe all over me."

Just about two years before COVID-19 descended upon a blissfully ignorant world, Bill Gates (yeah, that Bill Gates) warned us that a pandemic was coming and that it could potentially kill millions of people. He also said we weren't ready for it. "The world needs to prepare for pandemics in the same serious way it prepares for war," he said during a discussion hosted by the Massachusetts Medical Society and the New England Journal of Medicine. He also pointed out that today it's pretty terrifyingly easy for new diseases to spread all around the globe, that the next new disease might not be a flu, that government really needs to be able to mobilize the private sector to provide the tools we'll need to fight a pandemic ... ugh. Why didn't we listen to Bill Gates?

This other guy saw a pandemic coming, too

Back in January, Netflix debuted a six-part documentary called Pandemic: How to Prevent an Outbreak. No one paid attention, but you know, with 20/20 hindsight it would have totally been handy if we had. According to the Los Angeles Times, the documentary was directed by filmmaker and ER doctor Ryan McGarry, who is probably more of the latter than the former these days. McGarry made the film because he wanted the public to understand how the medical system would work — or is supposed to work — during a pandemic. As it turns out, he could have just waited a few months for nature to take its course, because we're all quite hyper-aware of those things now, but points for effort.

The series arrived too late to be much help, but it's still worth a watch because it highlights to what degree we all tried to pretend a pandemic would never happen. "We started looking into the people around the world and in the United States, whose entire careers were based on trying to make sure that [the 1918 flu] never happened again," McGarry said in an interview. " Yet most of these people, they were having their budgets slashed or they were not being taken seriously. And, well, here we are."

At least we can all take comfort in the fact that we can definitely, for sure, without a doubt learn from our mistakes and this will never happen again. Probably.

Carlo Urbani saw the deadly potential of SARS, and then it killed him

SARS wasn't nearly the pandemic that COVID-19 is, but it still killed a lot of people and caused some very real panic all across the globe. In many ways, it was our practice run for what we're going through right now, except for the part where we clearly sucked at our practice run because it didn't help us like, at all. Anyway, SARS is actually closely related to COVID-19 — the viruses are even similarly named: SARS is caused by the SARS-CoV virus and COVID-19 is caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (SARS and COVID-19 are the names of the diseases caused by those viruses, not the viruses themselves).

Anyway, when SARS-CoV first began to circulate back in 2003, Dr. Carlo Urbani visited a patient in Hanoi's French Hospital who was suffering from an unknown, severe, flu-like illness. Urbani diagnosed the illness in the only way he could, as an "unknown contagious disease," and then he alerted the World Health Organization (WHO). According to the WHO itself, Urbani's actions triggered a worldwide public health response that probably prevented the disease from becoming a truly global pandemic.

But Urbani did more than just diagnose that first patient — he stayed at the hospital to help coordinate the containment of the virus. And because that's what he did, he ended up contracting the virus himself and becoming one of its first victims. Urbani died from SARS complications on March 29, 2003.

John Brownstein built a tool that saw ebola coming

Ebola never really became a pandemic, for a number of reasons. For a start, Ebola doesn't spread through airborne droplets like so many respiratory illnesses — you have to have close contact with a very sick person in order to contract Ebola, and then you have to be very sick yourself in order to pass it along. Compare that to SARS-CoV-2, which you can pass along to someone even if you aren't symptomatic.

The 2014 Ebola epidemic was by far the most widespread and the most severe of all the Ebola outbreaks, with more than 11,000 deaths and 28,000 infections. According to Health IT Outcomes, nine days before the World Health Organization declared that the outbreak had become an epidemic, an online disease tracking tool called "HealthMap" identified the "mystery hemorrhagic fever" in southeastern Guinea using algorithms that analyzed data from news, social media, and government websites. John Brownstein, who co-founded the company that built HealthMap, intended for the tool to be used to find signs of outbreaks very early on, even before public health agencies can typically find them. So how did HealthMap do with COVID-19? By February, it was mapping the virus across China and in places like Tokyo, Chicago, and Paris. But alas, all the kids went on spring break anyway, and the rest is everyone sitting in their houses binge-watching Netflix because there's nothing. Else. To. Do. The end.

Venice invented the quarantine

Hundreds of years ago, epidemics were kind of a way of life. If it wasn't smallpox it was the Black Death and if it wasn't the Black Death it was the sweating sickness and if it wasn't the sweating sickness you were starving to death because poverty was normal for like 99.9 percent of the population and everything sucked anyway so in the grand scheme of things, what's another dumb epidemic, right?

Anyway of all the diseases that terrorized people in centuries past, it was the Black Death that seemed to dish out the most horror. Black Death — also known as bubonic plague, is caused by the bacteria Yersina pestis, which is carried by the fleas that infest black rats. And black rats were kind of a big problem in those days, because they followed people around eating their grain and garbage and dying and then leaving their fleas all over the place.

No one knew this back then, but they did know that people with plague begat more people with plague, and in the mid-1300s Venetian officials could see that the next epidemic was imminent. Instead of just accepting their fate, though, they implemented a rather modern idea — they decided to put all arriving sailors in isolation for 40 days until officials could be sure those travelers weren't carrying the plague. According to History, the word for this forced isolation was "quarantio," which is where we get the word "quarantine."

The epidemic potential of AIDS was pretty obvious to those who were paying attention

Most of us think of a pandemic as something that swoops in practically out of nowhere and upturns civilizations on a matter of months, leaving nothing but grief and fresh graves in its wake. But pandemics can creep through civilizations, too. In fact one of the world's most devastating pandemics took years to take its full toll on the world, and today it's still ranging — albeit slowly — in some parts of the world. The AIDS epidemic has killed around 32 million people since it was first identified in the 1980s. Just to put that into perspective, the Black Death — history's most infamous outbreak of the plague — only killed around 25 million. Granted, that was a much higher percentage of the population, but in terms of individual deaths AIDS is the clear winner.

In 1986, a doctor named David Baltimore warned that the AIDS outbreak was a lot worse than the federal government was making it out to be. According to the New York Times, Baltimore, who was chairman of a committee that released a dire report on the subject, told reporters that the National Academy of Sciences was "quite honestly frightened" by the epidemic potential of the virus. In the report, the agency warned that "if the spread of the virus is not checked, the present epidemic could become a catastrophe." Which, as we all know today, turned out to be pretty prophetic.

The WHO wasn't really that fussed about Zika

Zika is just one of many mosquito-borne illnesses. The Zika virus is related to yellow fever, dengue, and West Nile, and it's not as new as you probably think it is. Zika was first identified in a rhesus monkey in 1947, but it wasn't until 2015 that it became obvious how easily the disease might become a pandemic.

In early March of 2016, a doctor named Daniel R. Lucey published an article in the Journal of the American Medical Association that identified Zika as a disease with an "'explosive' pandemic potential." At the time, outbreaks were happening in 20 different countries in North and South America, and in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific Islands, too.

No one really freaked out about Zika, though, even though it was all over the place. That's because Zika mostly causes mild disease — with a few exceptions, including some scattered cases of Guillain-Barre syndrome and an elevated risk of a birth defect called microcephaly that sometimes shows up in infants whose mothers contracted the virus. In Lucey's paper, he warned that public health organizations should issue travel advisories and caution people to avoid mosquitoes (because that's possible). He also complained that the WHO wasn't really doing much about Zika. By the end of the pandemic, though, the birthrate in Brazil was down by more than 100,000 births, which indicates that the public was taking Zika seriously if everyone else was not.

The Obama administration reacted to H1N1 when there were only a handful of US cases

H1N1 took everyone by surprise in the spring of 2009, which is very much the tail end of flu season. Nicknamed "the swine flu," the virus kind of looked like influenza viruses carried by pigs, although there isn't really any evidence that this particular swine flu actually originated in our smelly, mud-loving friends. Swine flu was pretty scary, though it didn't seem to bring the same kind of abject terror as COVID-19 has. It spread across the world for about a year, infecting 60.8 million people in the US alone, and killing 12,469 of them. That sounds bad, but according to FactCheck, the overall mortality rate for H1N1 was around .02 percent, which is actually better than some seasonal flus.

Still, the Obama administration was extra-cautious when the virus arrived in the United States, declaring a public health emergency less than two weeks after the first U.S. case was identified in California. Things happened fast after that — that same day the CDC released antivirals to treat the infection, and a new test was approved just two days later. Within six months, there was a vaccine. So why can't we do that with COVID-19? Influenza is something we've been fighting for years, and we already know what kinds of antivirals work on them, and how to make flu vaccines to protect people from them. COVID-19, unfortunately, isn't influenza, which means in many ways we're starting from scratch.

The governor of Vancouver Island knew how to stop smallpox, but no one listened to him

On a scale of one to epically messed up, smallpox is like the most epically messed up virus of all time. Smallpox killed hundreds of millions of people — 300 million in the 20th century alone. Those it didn't kill it left horribly disfigured. And when Europeans brought it to the New World, it mercilessly wiped out Native Americans, who had no previous exposure to the virus and no natural immunity. During the French and Indian Wars, it was even used as a biological weapon.

By the mid-1800s everyone knew, or at least should have known, that smallpox outbreaks had the potential to cause widespread disease, and shortly after the steamship Brother Jonathan brought the first case to Victoria, British Columbia, governor James Douglas of Vancouver Island — who had experienced smallpox epidemics before — proposed building a hospital to help contain the spread. According to History Link, Douglas' idea was shot down by the House of Assembly, who called the governor an "alarmist" and argued that a hospital would be too expensive and would be an affront to the liberty of sick people. Meanwhile, authorities were actually vaccinating people — but only whites. Their inaction and reluctance to implement a quarantine ended up costing the lives of more than 14,000 natives, who were unprotected, vulnerable, and pretty much ignored when the disease started to spread through their communities.

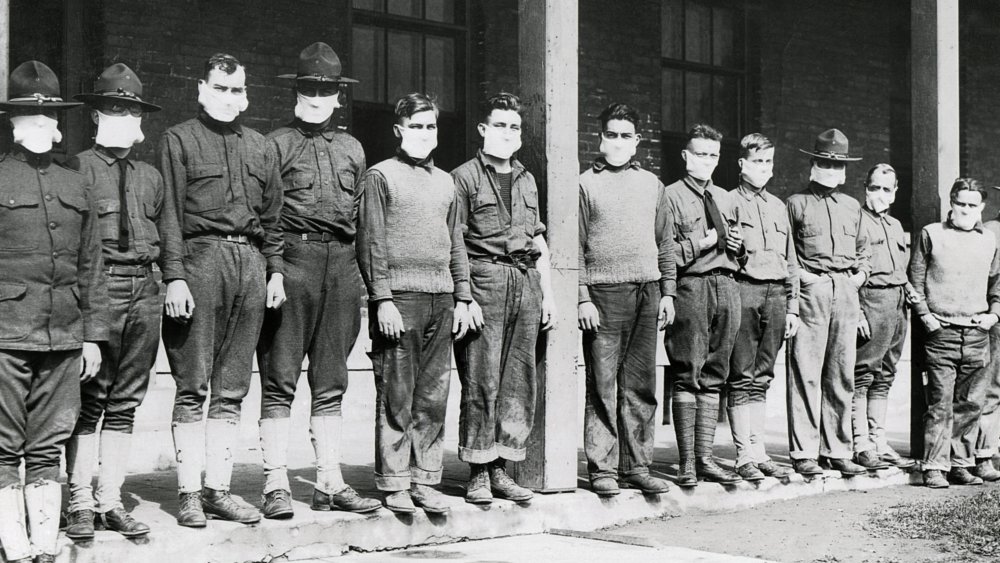

Loring Miner warned the Public Health Service about the 1918 flu

Towards the end of January in 1918, Dr. Loring Miner was called to see a patient with body aches, fever, a headache, and a dry cough. It was clearly influenza, but something about the patient's symptoms worried him. They were more severe than typical flu symptoms, and as the days went on and more people became ill, it also became obvious to Miner that the virus was killing a disproportionately large number of young, strong adults.

Miner searched medical journals for answers, did studies in his lab, and even tried giving his patients vaccines for unrelated diseases in the hope that the vaccines would boost their immune systems. According to the Fort Morgan Times, he reported the outbreak to the Public Health Service, too, but at the time, influenza wasn't on the list of diseases they were watching out for. For most of that year, Miner was the only one talking about "influenza of severe type," and no one was really listening.

The virus might have remained localized — this was before air travel was a way of life, after all — except that World War I was still raging and soldiers were traveling to and from base, going home on leave, shipping out, and bringing virus with them. By the end of the outbreak, an estimated 50 million people were dead.

Everyone laughed at Benjamin Rush

The spring of 1793 in Philadelphia was mild and wet, and by June it was hot and dry. Mosquitoes were a prolific problem that summer, though no one was aware of the link between the annoying insects and the yellow fever epidemic that was descending on the city.

Most of the early cases were poor refugees, French settlers who arrived in Philadelphia after fleeing a slave revolt and epidemic in the West Indies. Most of the first victims were ignored, because they were poor and no one liked poor people, except for other poor people. But according to the Proceedings of Baylor University Medical Center, a doctor named Benjamin Rush noticed what was happening — he'd seen a few yellow fever patients in his practice, and by the middle of August, he was convinced that an epidemic was brewing. Rush made a public announcement, and everyone went, "Oh okay let's start social distancing and preparing for the worst." Just kidding. Rush was accused of being an alarmist and basically laughed out of town by people who were like, "At the end of the day, I'm not going to let this stop me from partying."

By the final week of August, it became clear that Rush was right. The funeral bells were tolling pretty much non-stop and people were fleeing the city. At least 4,044 people died. Rush himself, desperate to save as many people as he could, ended up losing his reputation over his draconian and ineffective treatments.