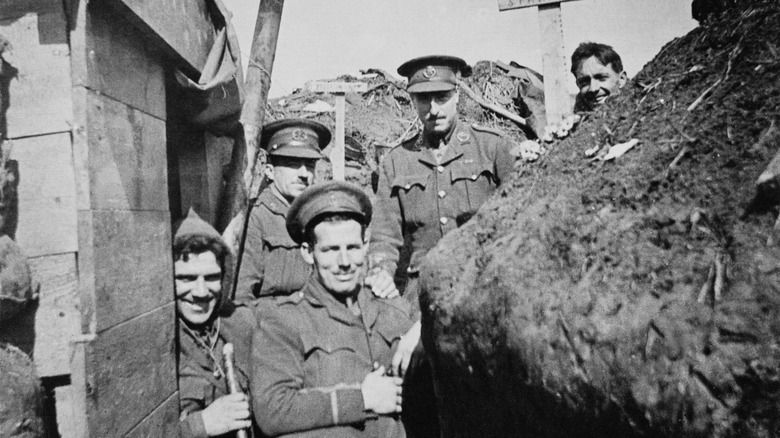

What Life Was Really Like In The WWI Trenches

Trench warfare was a major part of World War I. While trenches weren't exactly a new invention at that point, WWI scaled things up to a completely new level. The fighting sides started digging trenches early on, and the structures soon became one of the conflict's most defining elements.

The Western Front of the Great War was a massive area of rarely moving front lines, located mostly in France and Belgium. From 1914 to 1918, millions of soldiers were stationed in giant, fortified trenches while trying to wear each other out with machine gun fire, artillery, infantry attacks, and other terrifying weapons of war. While trench warfare itself was nothing new, many elements WWI brought to it very much were, so the soldiers stuck in these glorified pits had to face all sorts of challenges and horrors they were completely unaccustomed to. But what was the day-to-day life in the WWI trenches like? What did the soldiers have to deal with, apart from the elements and the enemy? Let's find out.

A WWI trench was a complex system

It's one thing to dig a hole and sit in it. It's completely another to do so when the enemy is trying to kill you. Because of this and the fact that the armies spent such a long time in them, the trenches in World War I were often elaborate systems that were designed to be as defensible as possible, with machine gun stations and barbed wire facing the enemy.

According to historian Paul Fussell, there were three main types of trenches. The machine guns-and-barbed-wire ones were called firing trenches, while others were known as communication trenches. There were also smaller "sap" trenches, which allowed the soldiers to advance beyond the safety of the outpost line for various purposes. The average trench consisted of multiple long "main" trenches, connected by smaller ones. The system contained the essentials the soldiers stationed there needed to operate, from command posts to shelter and kitchen facilities. As an additional defense element, the trenches usually twisted and turned in a zig-zag pattern to prevent enemy fire from the side.

The armies started digging as early as September 15, 1914 — mere weeks after the war began on July 28. The trench setups snaking all over the Western Front became more and more complex over time. The German forces took their trench game particularly seriously, using concrete and elaborate designs to reinforce their trenches.

Artillery could get you in a number of awful ways

Though trenches offered a measure of safety, they were by no means invulnerable. The key offensive element of World War I was artillery, which could come in many nasty shapes and forms. The advanced WWI artillery was a far cry from the popular image of mortars and cannonballs, though versions of these classics were also used.

Artillery was everywhere and could strike at any time. When it came, it came hard. As an example of how full of death the skies over the trenches could be, one five-day period of combat during the Battle of the Marne involved a total of 432,000 fired artillery shells. If you think that a trench — no matter how well-made — can't possibly protect soldiers from that much firepower, you're absolutely right. Artillery and explosives were responsible for an estimated 5.82 million of the war's 9.7 million military deaths.

The armies used many different types of cannons that fired a vast array of shells. Explosives were only the beginning of the artillery arsenal, and the shells could contain anything from shrapnel to chemical warfare agents.

Chemical warfare was a constant risk

One of the lesser-known nicknames for World War I is "the chemist's war," and the story behind this moniker is also the reason WWI-era soldiers had to incorporate gas masks into their equipment. If the atomic bomb is the most infamous weapon of mass destruction in World War II, WWI is known for terrifying chemical weapons.

Germany kicked open the war gas door when it used chlorine gas against French and Algerian troops near Ypres on April 22, 1915. The gas cloud killed over 1,000 people and the choking survivors fled the scene in panic — after all, effective gas masks weren't yet a thing, and it was this attack that helped spur their development. Ater this, multiple gases were used by both sides, with the lingering, blistering mustard gas easily being the most damaging chemical agent of the Great War.

Apart from the danger they posed, gas weapons were a potent psychological weapon that caused so much fear that a single soldier's sore throat could cause mass panic (via BBC). That's not to say the fear was unfounded, though. According to the University of Kansas, chemical weapons killed 91,000 people in WWI, but that was just the tip of the iceberg. The Imperial War Museums report that only 3% of gas attack victims died, and a great number of survivors suffered from the effects long after the war was over. No wonder the gas alarm gong was one of the more unwelcome sounds you could hear in the trench.

Diseases and shell shock ran rampant in the trenches

World War I trenches weren't the most sanitary places, and with lots of men spending time in these relatively confined spaces, diseases were a serious risk. The conditions even contributed to an epidemic of a strange illness that became known as trench fever, courtesy of the lice that infested the trenches (via Yale University Library). As if this wasn't enough, soldiers also had to deal with a laundry list of more famous but equally unpleasant ailments, from typhoid fever to dysentery.

Not all the health troubles the men in the trenches had to deal with were physical, either. Many soldiers fell victim to a condition called shell shock. This was a type of post-traumatic stress disorder that was initially attributed to a concussion-like reaction to artillery explosions but soon turned out to be a psychological issue. Shell shock often involved tremors, trouble with hearing and vision, and anxiety.

Some estimates suggest that British troops alone had as many as 325,000 shell shock cases. After the war, men who clearly still suffered from the condition weren't an uncommon sight. "Certainly one met people who were — different, and it was explained of their being in the war," said Sir Ilay Campbell (via Smithsonian Magazine), whose grandmother ran a convalescent home for WWI soldiers. "But we were all brought up to show good manners, not to upset."

Rats were everywhere in the trenches

Humans might not have found the World War I trenches enjoyable, but rats very much did. As soldiers found out to their deep dismay, rats absolutely loved the fact that millions of humans were suddenly killing each other while living in filthy holes, and took the opportunity to thrive. Both the size and numbers of the Western Front's rat population grew greatly over the course of WWI, caring little of the artillery attacks and carnage around them but warmly welcoming the human and animal remains that nourished them.

Understandably, the soldiers in trenches weren't thrilled with the fact that giant rats were everywhere, especially since the rodents grew increasingly unafraid of humans, running around the trench like it was their home — which, in a way, it was. Still, since there was absolutely no way to cull the huge population, trench rats became yet another unavoidable thing the soldiers had to endure ... especially because it was clear that the humans were hopelessly outnumbered in this scenario.

"Rats were common, very common, you didn't dare leave a bit of food about or else there'd be swarms of rats round you," said WWI veteran James Harvey, describing the vermin situation in the trenches for the "Voices of the First World War" podcast (via the Imperial War Museums). "And all the time you didn't attack them, they didn't attack you. But on one occasion where we got a bayonet and stuck one — needless to say, we got out of that place quick!"

Trench warfare was brutal and gruesome

When trench warfare escalated to actual fighting, things could get extremely messy. Not only were the soldiers in the trenches subjected to artillery fire and chemical attacks, but on occasion, they also had to deal with combat that got considerably more up close and personal.

One of the most certain ways to die in World War I was to leave the trench and attack the enemy on the "No Man's Land" between your own and the enemy's front lines — while said enemy was still entrenched. This was roughly as effective as you'd imagine. Infantry attacks caused a great number of casualties, and the Imperial War Museums' "Voices of the First World War" podcast describes the commanders even sending the men copious amounts of alcohol before the disastrous Battle of Somme, which WWI veteran Donald Murray suspected was to appease them before the mayhem. "The previous night at about 12 p.m., each dugout had a stone bottle of rum put into the dugout –- a gallon bottle," Murray described. "And nearly every man was drunk, blind drunk. I thought to myself, 'This looks to me like a sacrifice.'"

Perhaps understandably, such tactics fell out of favor eventually. Instead, various sneak attacks on enemy trenches became the more popular infantry tactic.

The mud was everywhere ... and it wasn't always just mud

If you dig a huge ditch and enough people tramp around in it, it only stands to reason that there will be mud. This very much applied to World War I trenches, too — as new arrivals soon found out, to their boot-sinking shock. "I couldn't believe it; I was knee-deep in mud for a start," WWI soldier Walter Hare described his frontline experience in the "Voices of the First World War" podcast. "I'd never been told about the Somme and the mud on the Somme, it was all new to me."

Knee-deep mud is already challenging enough, but in some trenches, the mud could be an even worse enemy than the opposing army. In 1917, the Third Battle of Ypres in Passchendaele, Belgium, went down in history not because of either side's military achievements, but because of the extreme rainfall and the lethally dangerous mud situation this created. Trench walls caved in, suffocating and drowning the soldiers inside. The slimy, sticky mud itself was so deep and dangerous that in some places, it functioned like quicksand.

Still, perhaps the most terrifying thing about the WWI trench mud was the fact that it wasn't just earth and water. As WWI veteran Francis Dillon told the BBC, the trench sludge had a strange, surprisingly sweet candy-like smell. Unfortunately, this was caused by decomposing bodies and traces of chlorine and mustard gas.

Trench life wreaked havoc on soldiers' feet

Being in World War I trenches for prolonged periods of time could be hazardous to your health in many ways, but it posed a very particular danger to the soldiers' feet. There's a condition called trench foot, which manifests as a series of increasingly nasty symptoms that can even lead to amputation, per a report published in the journal Wilderness and Environmental Medicine. As the name implies, this nasty condition is intimately connected with the trenches of WWI, where it first manifested in 1914. The conditions in the trenches meant that the men's boots were often submerged in cold water, which proved to be a perfect recipe for trench foot.

The condition causes tissue damage, swelling, and pain that's similar to frostbite. It was a major issue in the moist WWI trenches and affected 75,000 British soldiers alone. The military tried to deal with the situation with coordinated foot inspections and emphasizing the importance of foot hygiene. According to Healthline, if preventive measures failed, the condition was primarily treated with bed rest and various foot ointments, including one that contained opium and lead.

Soldiers did what they could to keep things cozy

By and large, trenches were drab and functional places that existed out of one necessity alone: warfare. Trench warfare also involved a lot of waiting, which left the soldiers with plenty of time on their hands. Some trenches highly benefited from this downtime, as the men did what they could to make their muddy abode as comfortable as they could. Troops on both sides who were fortunate enough to have their trenches connect to existing quarries used these relatively mud-free spaces to construct elaborate shelters, painstakingly decorated and complete with amenities that could range from chapels to bakeries.

Even those who didn't have access to such luxuries did what they could to make their trenches as livable as possible, putting an effort into construction and decoration, and naming their dugouts. Per the Veterans History Museum, many soldiers also turned to peculiar trench art – artworks, custom gear, and elaborate everyday objects they made with the materials available to them, ranging from simple wood to artillery shell casings (pictured). Soldiers also used to take their minds off the grim reality of trench warfare by writing letters to their loved ones. Being the only way to communicate with the home front, this pastime was so popular with soldiers that the British troops alone sent and received an estimated 2 billion letters during WWI.

The Christmas Truce offered a brief ray of hope

Life in trenches was often difficult, but on Christmas 1914, something miraculous happened to offer the soldiers on both sides a rare respite from the grim realities of the Great War. From December 24 to December 25, soldiers stationed along an estimated 20-mile stretch of the front lines simply stopped fighting, without any official planning. This so-called Christmas Truce followed a period of intense fighting and awful weather, which turned for the better just before Christmas. The battlegrounds received a thin snow cover, and the Germans even had Christmas trees to celebrate the holiday.

The Christmas Truce started with soldiers singing Christmas carols to each other from their trenches, initiated by Saxon soldiers of the German military. What followed was a magical event where soldiers of both armies came out of their trenches to drink, sing, celebrate, exchange gifts, and play soccer. Some of the savvier troops also used the temporary cease of hostilities to fix up their trenches and bury their dead.

It's worth noting, however, that the Christmas Truce was a singular event, made feasible by highly specific circumstances and possibly inspired by an unsuccessful truce initiative by Pope Benedict XV. The WWI Christmases that followed saw no such camaraderie between enemies. This may be because the soldiers on both sides had already seen too many horrors of the war at that point... though it certainly didn't help that higher-ups actively worked against turning the truce into a tradition.

The trenches fell when tanks arrived

Massive and well-defended as World War I trenches were, their barbed wire-and-gunfire defense systems had one massive Achilles' heel: tanks. The British created tanks specifically to break the trench stalemate, and after they rolled out their first tanks at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette in September 1916, the clock was ticking for trench warfare.

For soldiers accustomed to the flow of trench combat, facing these new armored vehicles was understandably terrifying. "It was terrifying because we couldn't stop it!" British officer Andrew Bain described facing a German tank for the first time on the "Voices of the First World War" podcast. "There were no anti-tank guns in those days. Rifle bullets just skidded off them like peas, you see. And it was rather terrifying to see this thing coming and you knew that you couldn't stop it."

It took until 1918 for tanks to become a truly reliable and common fixture on the battlefield, but when they did, the mobile war machines effectively signaled the end of the trench's heyday. Trench warfare wasn't a major element of World War II, and has only been used sporadically since mobile war machines became commonplace.