What Life Was Really Like For Roman Gladiators

If all you know about the life of a Roman gladiator is Russell Crowe's cry of, "Are you not entertained?" then you have been exposed to a gross distortion of reality. While gladiatorial combat certainly was one of the premier forms of entertainment in the Roman world, there are parallels with modern sports and all the sophistication — and drama — that we recognize with popular elite athletes.

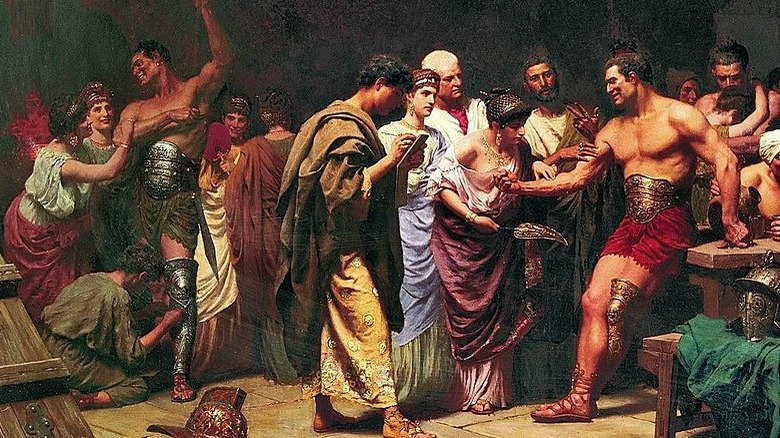

Gladiator contests started as private events at least as far back as 264 B.C., but they took off as public spectacles in the first century B.C., put on by the rich and powerful to display status and help maintain their power by entertaining the masses. While gladiator movies often portray the life of these fighters simply as one of enslavement and barbaric fighting in front of bloodthirsty mobs, there is much more complexity to the lives of these bloodsport contestants. From vegan diets to family lives to unfathomable wealth, let's look and see what life was like for these ancient fighters.

A diverse workforce

The gladiator industry was, to some degree, an equal-opportunity profession. While most gladiators were enslaved people, criminals, or prisoners of war, they might find themselves training with and fighting nobility, free people, and both men and women from all strata of society.

Sometimes, free and once-wealthy Romans signed up to become gladiators when they faced a financial cliff. For example, according to Michael Grant's "Gladiators," the Roman poet Juvenal lamented how one Sempronius, a descendant of the aristocratic Gracchus clan, had found himself in such circumstances that he resorted to a gladiatorial career. For other free people, the associated glory of armed combat before an enthusiastic and bloodthirsty crowd was the appeal. The most prominent example of upper-class thrill-seeking Romans going gladiatorial is the insane and sadistic emperor Commodus (he thought he was a reincarnation of Hercules), who actively fought in the arena, although the outcome of Commodus's matches were effectively determined in advance — with him as the victor.

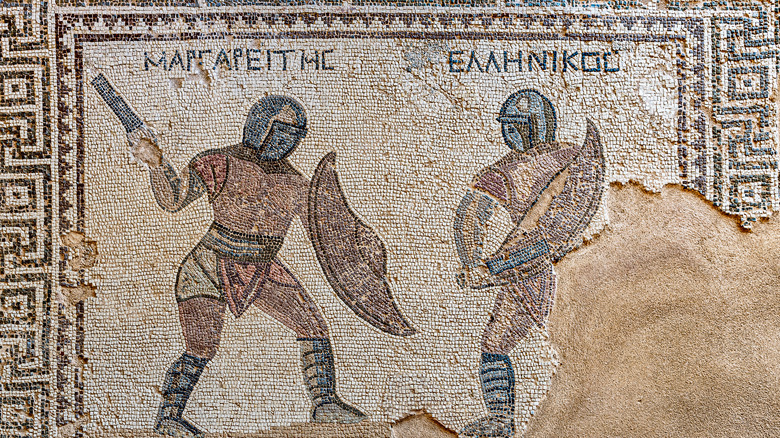

For centuries, gladiator fighting was not gender exclusive, either. Until A.D. 200, when the emperor Septimius Severus outlawed the practice, women fought as gladiators. Although the vast majority of gladiators were men, female contests were a niche that had its appeal in some quarters. The emperor Domitian in particular seemed to enjoy these fights, setting up bouts by torchlight. Some of these female gladiators came from aristocratic stock (to great scandal), though it is unclear why they signed up for the bloodsport. But for these women gladiators, like the men, the spectacle was still central, and they took on mythological names like Amazon and Achillia.

[Featured image by Carole Raddato via Wikimedia Commons | Cropped and scaled | CC BY-SA 2.0]

Years of training before fighting

Gladiators were not just given a sword or trident and told to start hacking and stabbing. Instead, gladiators were subject to years of intense training for what may amount to only one public bout. Rachael Hannel, in her book "Gladiators," explains that this is because, as the games grew in popularity, it was increasingly evident how valuable well-trained gladiators were as a commodity. As the institution developed and popularity grew, the length of training a single gladiator might undergo grew to as many as three years of formal training — before their first, and perhaps last, appearance in the arena.

Trainees started with wooden weapons, hitting practice dummies or bales of hay. Eventually, trainees graduated to blunted metal weapons, examples of which, found in Pompeii, were heavier than the weapons to be used in the arena. These lessons were directed by trainers or managers, called lanistae, often former gladiators themselves, and multiple professional instructors would often teach specialized techniques. The training process was highly organized, complex, and widely revered in Roman society as an ideal example. According to Michael Grant's "Gladiators," the end result was a contest more akin to modern-day fencing, with precise movements that at least some spectators would be able to recognize and appreciate.

Much of gladiator training was also mental; the lanistae emphasized how special they were and how they were entering the ranks of an elite profession. And if the trainees lacked enthusiasm, harsh punishments were applied to break their will.

Family life (or lack thereof)

Many gladiators lived in cells within communal barracks, where the only people who they could associate with one equal terms were their fellow gladiators. And even then, there was a natural tension, since your colleagues could become your eventual killers. However, the "Oxford Handbook of Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World" points out that these fighters seemed able to separate their friendships from the bloody business in the arena. Gladiators formed clubs, guilds, and friendship networks, and all were very hierarchical, with veteran gladiators and newcomers occupying separate ranks.

Some gladiators went so far as to have families. These were not recognized as legal, but various epitaphs indicate that gladiators had wives and children, and one such epitaph notes how a young gladiator in his early twenties had died in his sixth year of marriage. Luciana Jacobelli, in "Gladiators at Pompeii," describes how the gladiator Urbicus was married for seven years before dying in the arena at age 22, after a career of 13 fights.

The gladiatorial family within the schools and their personal families were known to support one another, such as several recorded occasions of troops contributing to the funerals of the children of gladiators.

They usually lived in barracks

Much like professional soldiers have done throughout history, a gladiator would typically live in communal barracks, housed with a lively mix of enslaved or indentured fighters. The Romans referred to these as "ludi," or schools, and while some were privately owned, many were built and overseen by the emperors. Conditions were often harsh, with it not uncommon for gladiators to be kept in chains, and the cramped conditions, as well as the constant combat training the fighters were expected to do, created a tinderbox of violence.

Italy's Pompeii, famous for being buried under volcanic ash, has a particularly well-preserved building generally accepted to be a gladiator training school, and the gladiator accommodations were basic, to say the least — almost one hundred windowless cells crammed into two floors, measuring barely 10 feet by 13 feet. If this sounds much like a prison, consider this: the school also had a prison, with ceilings so low that prisoners would have been unable to stand, and evidence that the prisoners were chained by the legs.

Not all gladiator schools were so grim, though. The communal housing in many schools was divided into halls, where a gladiator would reside with others of the same or similar reputation. Imprisonment wasn't always a given, either, and in some cases, schools were much like non-military schools or academies in modern times, where the gladiators were free to leave and return as they wished. And the finest gladiators were sometimes given training in private houses, by high-ranking Roman military professionals or other martial experts.

Gladiators were attached to schools

A gladiator school, called a ludos, was no Ivy League college. There were many of these schools throughout the empire, and emperors even established their own. Julius Caesar himself started a famous ludos in Capua, which boasted 5,000 gladiators. The schools were typically well-organized, with accommodation for gladiators and staff, gymnasiums, and practice arenas. Not all were just general-purpose gladiatorial factories either: Emperor Domitian constructed several schools that specialized in different styles of combat, including the Ludus Matutinus, or "Morning School," which pitted gladiators against wild animals.

According to Anne Leen in "All Things Ancient Roman," a gladiator school's chief trainer and brutalist was the lanista (plural lanistae). The lanista was often a retired gladiator who served as the chief manager. Luciana Jacobelli, in "Gladiators at Pompeii," describes how lanistae served as the principal intermediaries between the elite who wanted to put on spectacles and the gladiator school. He was a dealer in flesh and could sell, buy, or rent gladiators. In fact, the term lanista is derived from the Latin term for "butcher." It was a lucrative but socially demeaning job.

The financial motivations being what they were, the lanista was motivated to keep his gladiators in the best shape possible. This way, he could fetch the best prices, and some of the best gladiators sold for so much that Emperor Marcus Aurelius put a price cap on them.

Gladiators ate a high-carb diet

Considering the popular image of muscle-bound gladiators hacking away at each other, one might expect their daily diet to have been heavy on red meat, fish, and otherwise generally rich in animal protein. However, gladiators ate a diet that would make a vegan proud.

A study published in PLOS One reports on archaeological excavations at a gladiator graveyard in Ephesus, Turkey. There, a study of 22 gladiator remains revealed that the main staple diet of these ferocious warriors was barley and wheat. For protein, the gladiators consumed legumes (i.e., beans). Moreover, they chugged down a tonic containing plant ash as their ancient energy drink to further fortify them, although subsequent flatulence in gladiator barracks may have been a real distraction.

This diet of barley and beans is confirmed in ancient writings. The ancient physician Galen, for example, reported that gladiators ate primarily a bean and barley porridge. In fact, gladiators were called hordearii, which translates to "barley eaters" or "barley men." The result of this high-carb diet was apparently gladiators with a high ratio of fat to body mass, and this conveyed a surprising advantage in their hazardous day job: Archaeology contends that a healthy layer of subcutaneous fat helped protect gladiators by providing layers over blood vessels and nerves, so a skinny gladiator may have been more likely to have their life quite literally cut short.

Social status (or lack thereof)

Despite the wild popularity of gladiatorial bouts, gladiatorial work as an occupation was viewed by most Roman citizens as disgraceful, on a par with modern-day convicted felons, or cold-calling telemarketers.

There were a couple of reasons for the denigration of the profession, which is explained in "The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome." First, gladiators, on the whole, came from disrespected elements of society, mainly enslaved persons or prisoners. Second, even if free people sold themselves to a lanista and became gladiators, it was a mark of disgrace, since the person was probably a financial basket case. In both cases, the underlying disgraceful element of the job was that the gladiator was now at the command of the lanista. They no longer had control over their own bodies and had no self-sovereignty. This is described by M.C. Bishop in "Gladiators," who points out that gladiators took an oath which, when reconstructed, reads: "I promise to endure burning, bondage, flogging and death by the sword to obey my master." In taking the oath, a gladiator (enslaved or not) had dehumanized himself.

Nonetheless, a gladiator's notoriety did not always get in the way of achieving celebrity status, and some — like celebrities today — found their names and depictions celebrated in poetry and pottery alike. But even an A-lister gladiator would find their status, dubbed "infames," subject to certain restrictions, such as being unable to enter the highest political ranks or, if they had been freed from enslavement, become a Roman citizen.

Bouts were intense

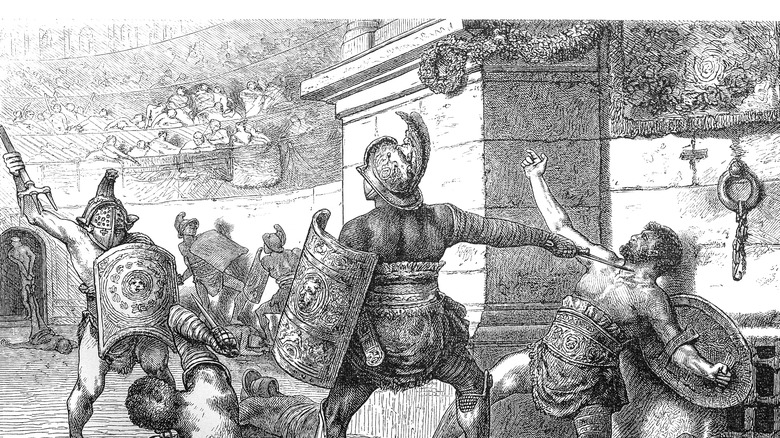

Gladiator bouts were no doubt exciting to watch, but they weren't especially long — so there were plenty of them, and the lead-up took up the rest of the slack.

While gladiator games evolved over their long history, during imperial times, the events were a full-day spectacle. According to the University of Chicago, the gladiators proceeded through the amphitheater before presenting themselves to the emperor if he was present. Criminals who were condemned to death would state, "Ave, imperator, morituri te salutant!" This translates to, "Hail Emperor, we who are about to die salute you!" Regular gladiators, on the other hand, didn't say this.

Before the main bouts, there were exhibition duels, sometimes with wooden weapons, all to get the crowd excited. After this warm-up act, a trumpet blew. This was the signal of the official games and was joined by a cacophony of a roaring crowd and music. The gladiators entered the arena, and those who were reluctant were forced out with hot irons and whips. The matches themselves lasted up to 15 minutes, as although the fighters may have been well-trained and closely matched, their weaponry was more than capable of delivering a quick, killing blow. This was, in fact, about the same length of time that a modern mixed martial arts match lasts. Between the physical exertion of trying to kill a person and the sheer energy of having thousands cheer and jeer, it seems amazing that they lasted that long.

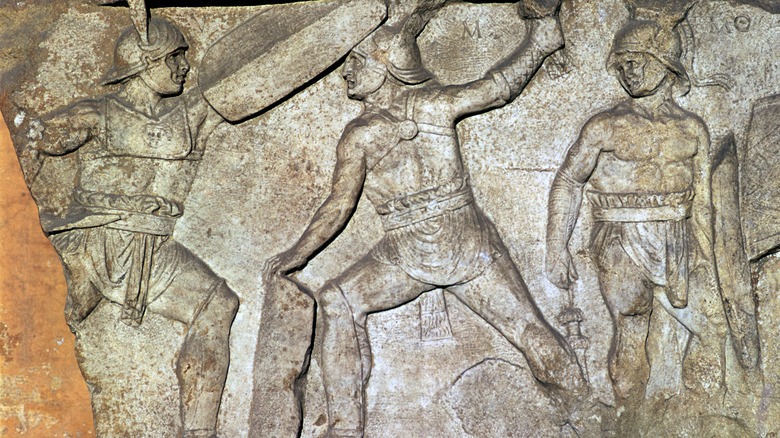

Fighters were specialized

To make things more interesting for the spectators, Roman gladiators were divided up into different classifications of fighters. Each type of fighter had different weapons and armor. As a result, this required that each fighter type learn to fight differently.

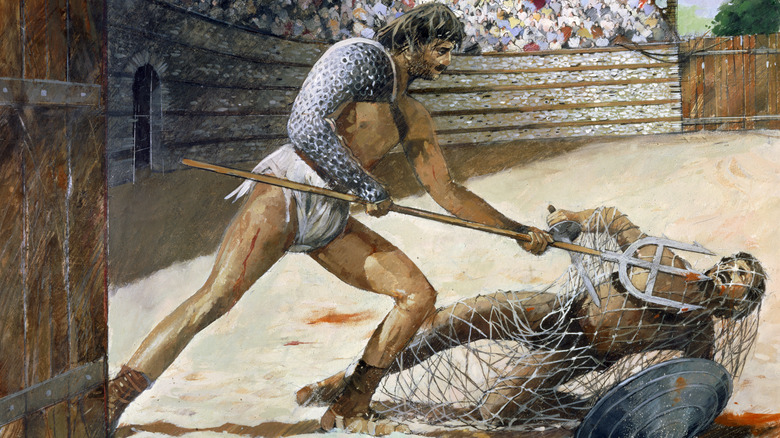

Within each classification, individual gladiators were ranked based on skill, which had practical effects on gladiatorial life. According to the "Oxford Handbook of Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World," gladiators probably lived and trained almost exclusively with their class and fighter level. Classifications changed over time, but the most well-known were the Samnite, Thracian, murmillo (myrmillo), and retiarius. Perhaps the retiarius is the most distinctive of these, with this class wielding a trident and net. There were many more specialized type fighters, such as the andabatae, who fought on horseback with closed visors so they couldn't see, and the dimachaeri, who wielded two short swords.

One particularly gruesome event — the venatio, or beast hunt — was not something gladiators typically trained for or partook in, with the human victims usually being condemned criminals or prisoners of war. But, were a gladiator to be trained in certain specialized schools, such as the Ludus Matutinus, or "Morning School," they might find themselves on a career trajectory facing ravenous beasts in the arena, albeit better equipped to survive than the aforementioned condemned prisoners.

Gladiators at work were deliberately paired

Mixed martial arts fans these days may compare one combatant's grappling skills against another's punching and kicking skills. Such spectator-driven matchups were the same for gladiators. Classes of gladiators were specifically paired with one another in fights, which displayed the strengths and weaknesses of the other. The idea (per the University of Chicago) was that fights were supposed to be fair, but fighters were not to be identical. This allowed for greater audience engagement, and encouraged gambling.

Most pairings involved a lightly armed fighter against a heavily armed one. The retiarius, for example, would often be matched against a type of murmillo called the secutor. The retiarius, being lightly armed with a net, small shield, and trident, would try to entangle the much slower and heavily armored secutor. A sturdy blow from the secutor would dispatch the net-man quickly. One may imagine how in a match like this, the retiarius would constantly run away from the secutor looking for an opportunity to toss his net over him — Secutor, in fact, means "chaser" or "pursuer." Likewise, the Thracian was usually pitted against the heavily armored murmillo. The Romans sometimes called this the difference between parmularii or scutarii (small-shield and big-shield men). Therefore it was rare to see two of the same class of fighters face one another.

Gladiators were on the job infrequently

Gladiators did not have nine-to-five jobs. Instead, they trained for years for infrequent appearances. In "The Eternal City," Ferdinand Addis writes that the average gladiator may have fought only one or two times a year, with the rest of the time spent training and traveling. Some epitaphs reveal that, over an extraordinarily long career, some gladiators were credited with fighting in as many as 60 matches, though this is very much on the high end of the spectrum.

While one to two fights per year may seem surprising to some, especially with how the gladiator life is depicted by Hollywood, this statistic has modern comparisons. Modern professional boxers, for example, only box up to three fights per year, with less than two dozen bouts on average in an entire career. These numbers also confirm the value of Roman gladiators as financial resources — the best among them needed to be saved and used with the greatest effect so that the most money could be made.

However, there are exceptions to this infrequent trend. For example, when the emperor Trajan held games, one gladiator fought in nine fights over the course of nine days. It must have been a genuinely terrifying and stressful experience for the gladiator, though it ended happily, since this particular gladiator was granted freedom at the end of the ordeal.

Gladiators had good health care (for ancient Rome)

Healthcare in ancient Rome may have been primitive when compared to modern medicine, but nonetheless, gladiators probably had the finest medical care available for the age. This, according to the German medical journal Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift, was because of their value. Gladiators were generally enslaved, but their worth to the gladiatorial school was so much that they needed them not just to be alive, but to be killers in a peak health condition.

The most well-known gladiator doctor was the 2nd-century physician Galen. He was from an aristocratic family, but in 157 A.D., he chose to become a physician to gladiators. It was an unusual step, especially when considering all things connected to gladiators was considered demeaning. For Galen's purposes, he used much of the experience to learn about the human anatomy and tinker with the gladiators' diet.

Aside from being patched up and otherwise well-tended, gladiators also had special services. For example, Roger Dunkle, in "Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome," notes that gladiators, especially in the preeminent imperial gladiatorial schools, were serviced by masseuses who worked on the knotted muscles of the fighters. This care may be why gladiators in these top schools were said to have better morale than in other backwater burg schools.

It was a death-averse profession

A gladiator's ostensible job was to kill or be killed, but in reality, it was a very death-averse profession. Luciana Jacobelli, in "Gladiators at Pompeii," explains that the value of the gladiators as entertainment commodities and the expensive costs of training them did not make them disposable commodities.

There were, naturally, several ways a gladiator could die, the most obvious being killed outright by his opponent, which is a real risk. Another way was when the "editor," who was the official and sponsor of the games, ruled that the defeated gladiator could not be spared, or the spectators demanded death. This usually happened only when the defeated gladiator didn't do his job correctly and really ticked off the audience with a bad show. When an editor ruled death, he had to pay the gladiator's manager, the lanista, the cash value of the gladiator. Therefore, there was little incentive for a ruling of death, and most defeated gladiators were likely spared. It is also clear that by the imperial period, not all gladiator matches were even to the death, but a good number were instead staged demonstrations.

Sometimes everyone was a winner

There were three ways a gladiator could exit the arena. The best way was through the Porta Triumphalis, reserved for victors. The worst way was through the Porta Libitinensis, by which the dead were hauled out and stripped of their weapons. The third option was for the defeated but spared gladiator who left shamefully through the Porta Sanavivaria.

However, there were occasions in gladiatorial combat when everybody could be a winner. One such occurrence was recorded by the satirist Martial, who attended games sponsored by Emperor Titus in the first century A.D. These games marked the opening of the famous Flavian Amphitheater (better known today as the Roman Colosseum). Among Martial's various epigrams, which included praise to a beast killer named Carpophorus, he recorded a contest between two gladiators named Verus and Priscus.

Verus and Priscus were equally matched and fought to a standstill. The crowd, evidently bored, started to demand a draw. Still, Titus, who was presiding, did not make a judgment, since he had established a rule that contests would continue to go on until somebody yielded. To placate the noisome crowd, Titus sent gifts to it, but eventually, the two gladiators yielded simultaneously. Titus was apparently relieved since he sent the two gladiators palms of victory and wooden swords — a symbol of retirement.

It could be lucrative

In the Roman Colosseum, there was blood to be spilled and money to be made. Fik Meijer in "The Gladiators: History's Most Deadly Sport" explains that most money went to the gladiator managers, the lanistae. If cash was doled out to the fighters, it was usually some token sum and a prize wreath or olive branch.

That being said, there were rare occasions when a gladiator hit the equivalent of the lottery. For example, the emperor Tiberius doled out a cool 100,000 sestertii to several veteran gladiators to lure them out of retirement. The notorious emperor Nero, a fan of the games, took a shining to a gladiator named Spiculus and granted him properties, which included a palace. In some cases, elite gladiators even worked out a percentage system with the lanista, where they kept a portion of the prize money. Enslaved gladiators were given 20%, while free gladiators got 25% — The rest went to the lanista. The Roman philosopher Seneca thought the whole gladiatorial system was corrupting and exploitive, likening the gladiators to cattle being farmed and butchered by the lanista.

It was a religious experience, but not really

Even though gladiator fights were wildly popular, there had always been moral objections to them. Seneca, in his Epistles, was disgusted by the gratuitous violence, writing of its impact on the soul: "Either you will be corrupted by the multitude, or, if you show disgust, be hated by them. So stay away."

It is impossible to know what the gladiators thought, but they may have shot back that gladiatorial combat had a religious purpose — at least in its beginnings. The Etruscans, the dominant city-state in Italy before the rise of Rome, deeply influenced the Romans. The Etruscans practiced various sacrifices to the gods, sometimes to honor them and sometimes as a form of divination. As part of these rites, they held warrior combat events as a death ritual at funerals, where the combatants would be assumed to journey with the demised to the afterlife as bodyguards.

Centuries later, virtually all the religious meaning behind the games had evaporated except for two vestiges. First, it was common to see person dressed as the messenger god Hermes, who sometimes struck a final blow after a gladiator had fallen. Also, at the most prestigious games, the emperor was present, who as Pontifex Maximus — the chief priest — along with the Vestal Virgins, gave the bloodletting a divine cloak of religious authority.

Heartthrobs and heroes

Gladiators had a low social status, but were still greatly admired for their strength and skill. Donald G. Kyle explains the reasoning behind their sex appeal in "Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome." He notes that the gladiators were the ultimate form of ancient machismo, who broke taboos through the violent eroticism of the games. In other words, they were the ancient Roman equivalent of the quintessential bad boy.

Roman graffiti, documented in Luciana Jacobelli's "Gladiators at Pompeii," reveals that gladiators received a lot of romantic attention, with one gladiator, Caledus, called the "heartthrob of the girls." Other evidence has been unearthed by archaeologists, including artifacts in which images of gladiators are shown juxtaposed with erotic images. It seems that the chief object of desire may have been the Thracian class of gladiators — their armor was more flashy and refined, which may have promulgated their reputation as sex objects.

The sex appeal of gladiators is also confirmed in literature. The Roman satirist Juvenal wrote how even aristocratic Roman women wanted to run away and have sexual dalliances with gladiators. Rachael Hanel in "Gladiators" relates how one gladiator nicknamed Flamma (meaning "The Flame) was so enamored of the crowds that even though he was freed from enslavement four times, he chose each time to return to the arena. Flamma finally died at age 30, after fighting 22 times.

Gladiators feasted before fights

Ancient Rome is notorious for its extravagant dining, and so it's no surprise that big games required big gladiator feasts. The night before matches, gladiators held a feast called the cena libera. Roger Dunkle, in "Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome," explains that the sponsor of the games arranged for the festivities. Not only did the gladiators enjoy copious amounts of expensive food and drink, but so did beast fighters and the damnati. The latter group were criminals condemned to death, and the cena libera seems to be an ancient invocation of the last meal rites. One can only imagine how these three groups interacted, but the idea behind them was for the games' host to show how thankful he was to the people who may die in his games, or in the case of the damnati, those who certainly would die.

The cena libera was a spectacle in itself. The feasts were held outside in a public area where people could interact with the participants, and so was a clever way of marketing the upcoming game. With the participants, though, there was also a lot of last-minute will-making, where arrangements were made for their wives and families.

Gladiator armor could be eye-catching

One thing that gladiators did not have to worry about in life was armor. Not only did they not have a lot of it, but what they had was provided to them by their gladiator school. Rachael Hanel, in "Gladiators," writes that most gladiator armor consisted of leg guards and a helmet, and in most cases, there was no protection for the chest. Of the different classifications, the retiarius was the most poorly armored, given just a shoulder guard. His usual opponent, the secutor, tended to be the most heavily armored, given a large head-to-toe shield and armor for the sword arm.

Some armor was more elaborate and created, no doubt, to show off the gladiator's physique. These pieces included plumed helms complete with engravings. However, again, the armor didn't belong to the gladiator. Konstantin Nossov, writing in "Gladiator: The Complete Guide to Ancient Rome's Bloody Fighters," reports that the equipment all went back to the school, and elaborate pieces would have been passed from generation to generation of gladiators. This may have occurred either through retirement or, just as likely, death.

Retirement was possible

Gladiators did not have a retirement plan per se; simply surviving each fight was the primary goal. Nonetheless, there were many gladiators who managed to make it through their careers alive and eventually retire. Those who did so were given a rudis, a wooden sword that symbolized freedom, along with their own freedom.

Retirement marked a new phase in the gladiator's life. Some, of course, could enter into civil life. Rachel Hanel in "Gladiators" explains how, as regular free agents, gladiators looking for work played to their obvious strengths. Some became bodyguards, or, in the disruptive period of the late Republic, were hired as muscle for gangs.

But the denigrated social standing of a gladiator, along with his inherent experience fighting, often led retirees to stay within the profession as trainers or even the heads of gladiator schools — due to their experience, they were often highly sought after by gladiator training schools. Then there were some rare few who, through prize money and aristocratic favor, could amass a small fortune. One notable example was Spiculus, a favorite of the infamous emperor Nero, whose victories in the arena landed him with wealth beyond most Romans' wildest dreams — and who met his end not in combat, but under a toppled statue of Nero during a riot.