The Messed Up Truth About The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire was one of the most devastating industrial accidents in this nation's history. In under 20 minutes, the accidental blaze killed 146 garment workers in downtown Manhattan on March 25, 1911. Many of these deaths could have been prevented, but due to lax fire safety laws and few labor regulations, unsafe working conditions prevailed in New York's garment factories in the early 20th century.

In the aftermath of the tragedy, workers and labor activists were galvanized into action, joining together to call for labor reform. Politicians and the public took notice, and a series of laws and regulations were passed to make workplaces safer and improve working conditions in New York City. Even today, the Triangle Factory fire remains an important symbol of organized labor reform. The building where the tragic accident took place still stands, designated as both a National Historic Landmark and a New York City landmark. A monument to the victims stands in Brooklyn's Cemetery of the Evergreens, where six unidentified bodies from the tragedy are interred.

The Triangle Shirtwaist factory was a modern industry standard

The Triangle Shirtwaist factory was housed in the top three floors of the Asch Building, which stood on the corner of Greene Street and Washington Place in Greenwich Village. Working conditions in the factory were inadequate by today's standards. Factory workers worked long hours in cramped workspaces, amidst dangerous and flammable materials, with few health and safety precautions. However, work in the garment industry was known for being difficult and dangerous, and, by early 20th century standards, the Triangle Factory's new address was considered an exemplary model of the modern factory. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the building was newly constructed, only 10-years-old, with 27,000 square feet spread out over the eighth, ninth, and 10th floors.

The well-lit high-rise, outfitted with new, well-maintained equipment, was a far cry from the tenement factories that had been pervasive the previous century, where workers toiled away for long hours in cramped, dark, dilapidated apartments, per Timeline. Tragically, however, the high-rise proved to be significantly more dangerous in one very important way: with its multiple stories and limited exits, the building was a firetrap waiting to happen.

Working conditions in the garment industry were abysmal

Despite its modern amenities, work at the Triangle Factory was still exhausting, hazardous, and largely unregulated. The owners of the factory, Isaac Harris and Max Blanck, had made $1 million in sales (about $30 million today) by 1908, per Forbes. But their profits often came at the expense of their workers' health and safety.

The Triangle Factory workers were predominantly immigrant women. Shirtwaist making was a high-risk job with low pay. Employees, some as young as 14, worked 12 and a half hour days, every day, and made around six dollars per week, according to AFL-CIO. In November 1909, the shirtwaist factory workers went on strike, demanding an increase in wages, a 52-hour work week, and an improvement to seasonal unemployment, per the National Museum of American History. They organized an industry-wide walkout that came to be known as the Uprising of the Twenty Thousand, marking the first labor movement in American history where women workers were the driving force.

Harris and Blanck resorted to violence to intimidate the picketers. Per the Washington Post, they hired goons to physically attack the strikers. In October, they hired a gang leader named Johnny Spanish to beat up Joe Zeinfield, a leader of the strike. In February 1910, the strike came to an end without an official union agreement. While Harris and Blanck did finally give in to shorter hours and higher wages, they remained staunchly opposed to worker unionization, per PBS.

The owners of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory had a suspicious history with fires

The Triangle Shirtwaist factory owners, Isaac Harris and Max Blanck (pictured center), were immigrants themselves, having moved to America from Russia in the 1890s, according to PBS. Like many Jewish immigrants at the time, they went to work in the garment industry. Harris was a skilled tailor, while Blanck made a name for himself as a garment contractor and salesman, per Forbes. Harris married Blanck's cousin-in-law, and in 1900, they went into business together. Their partnership coincided with the rise of the popularity of the ready-made clothing industry. In 1900, Harris and Blanck opened their first factory on Wooster Street, making a popular new lady's garment called shirtwaists, which were styled after menswear and were less constricting than a traditional bodice.

Their business boomed, and by 1902, it had grown enough to warrant opening a newer, bigger factory in the Asch Building. They continued to expand, opening factories throughout New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. By 1908, New York's "Shirtwaist Kings" were the largest manufacturers of blouses in the city, per PBS.

But Blanck and Harris had a history of their factories going up in flames. The Triangle Factory had already been the victim of mysterious fires twice in 1902. Another factory, the Diamond Waist Company, had also burst into flames twice, always before business hours, prompting suspicions Blanck and Harris were torching their own factories in order to collect on the sizable insurance policies, per History.

Fire safety was lax and unregulated

While Blanck and Harris' record of factory fires might seem suspicious, they were a common occurrence in garment factories. With no mandatory safety laws in place, fire prevention measures lay in the hands of factory owners. But Blanck and Harris were known to avoid implementing safety measures to keep costs down and profits high. The Triangle Shirtwaist factory was no exception. While the owners took out fire insurance policies, they did little to ensure worker safety in the event of an emergency. Per Smithsonian Magazine, the pair had neglected to install a sprinkler system. Fire drills were never performed, and no evacuation procedures were in place.

To make matters worse, Harris himself deliberately designed the sewing floor layout to prevent employees from conversing and wasting time, per PBS. However, this layout also resulted in crowded aisles that hindered free movement. A survivor of the fire, Celia Walker Friedman, recalled, "The aisles were narrow and blocked by the chairs and baskets... The door to the stairway was completely blocked by the big crates of blouses and goods," via Cornell University.

It was standard practice to put out fires with pre-filled water buckets that were strategically hung throughout the factory. However, these were not regularly checked, and on the day of this fire, the buckets were empty. Similarly, the single fire hose was old, rotten, and rusted shut, rendering it useless, per History. When tragedy eventually struck, there was no way to slow down the blaze.

An accidental ignition

On March 25, 1911, at about 4:45 p.m., according to Forbes, the work day was almost finished when a spark was ignited in a rag bin on the eighth floor. Per Smithsonian Magazine, the most likely cause of ignition was an unextinguished cigarette. Because very few women smoked at the time, it probably belonged to one of the cutters, a job held only by men. Although there were rules against smoking in the factory, they were not strictly enforced. Cutters would often sneak smokes while working, exhaling into their jackets to prevent detection.

Cotton scraps, paper waste, and material dust caused the fire to quickly spread to the ninth and 10th floors, and panic ensued. Employees on the eighth floor reached the exits first, and many were able to escape. Workers on the 10th floor, which included the owners Harris and Blanck, were able to make it to the roof and escape to neighboring buildings. Per Forbes, Harris told his workers: "Girls, let us go up on the roof ... I cried to them to go up the Greene Street stairs, and at that time the smoke was very thick in the room there and it was getting very dark."

But, a telephone operator evacuated instead of alerting the ninth floor. Without the early warning, the ninth floor was trapped before they were even aware of the fire.

Bottlenecks and broken elevators prevented workers from evacuating

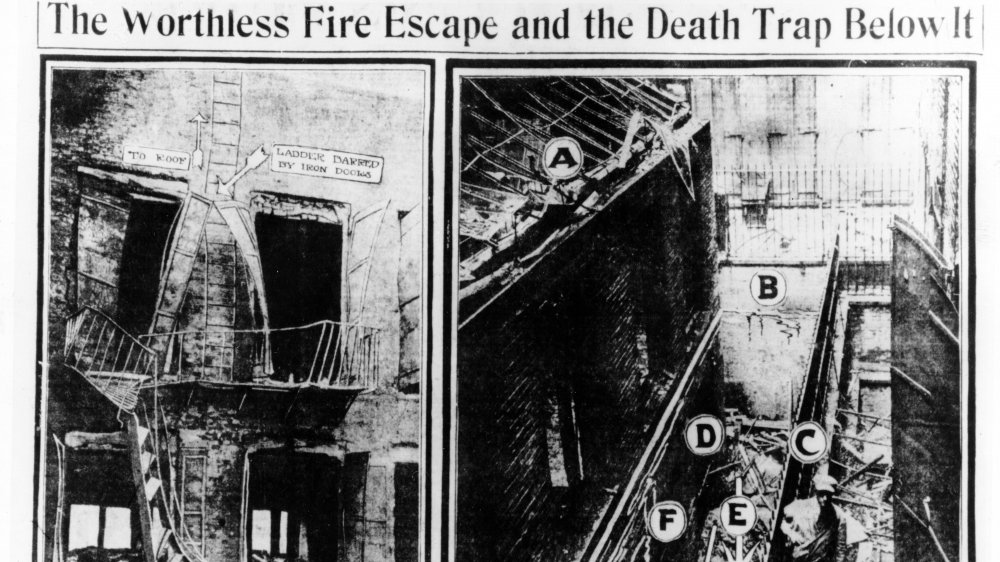

The ninth floor, with few exits and no early warning of the emergency, bore the brunt of the tragedy. Bottlenecks built up as workers raced to exits, only to discover they were blocked. The building had only one fire escape, despite needing at least three to accommodate all 500 factory employees, per Baruch College. It was too narrow to allow many people to pass through, and it buckled from the heat and weight of all the workers rushing onto it from the ninth floor.

The main point of escape was a single elevator, which could fit just 12 people at a time. The operator only made four trips before it broke down, per History. Some girls tried to escape by sliding down the cable, causing many to fall to their deaths in the shaft.

Celia Walker Friedman, who survived the elevator shaft, recalled: "I was left with those who didn't make the first trip. Then the elevator came up a second time ... I rushed with the other girls but just as I came to the door of the elevator it dropped down right in front of me. I could hear it rush down and I was left standing on the edge trying to hold myself back from falling into the shaft ... Maybe through panic or maybe through instinct I saw the center cable of the elevator in front of me. I jumped and grabbed the cable," via Cornell University.

Some doors of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory were intentionally locked

The Triangle Factory had just one functional elevator and two staircases leading outside: one opened onto Greene Street, and the other onto Washington Place. Flames on the ninth floor blocked the Greene Street stairway, leaving only one exit. However, to prevent theft, the owners had locked Washington Place exit. Per the Washington Post, it was common practice at the time to secure all exits except one, which employees were required to pass through and have their bags inspected for stolen goods before they were permitted to leave at the end of each work day. This policy turned out to be lethal. With no open stairways, the only viable fire exits were the dangerous elevator, which ultimately failed, or the single inadequate fire escape.

With no other way to get out, some workers resorted to jumping from the top floors of the factory rather than burn to death. An onlooker to the fire, William Shepherd, described the horrific sound of the jumpers as "a more horrible sound than description can picture. It was the thud of a speeding, living body on a stone sidewalk. Thud—dead, thud—dead, thud—dead, thud—dead. Sixty-two thud—deads. I call them that, because the sound and the thought of death came to me each time, at the same instant. There was plenty of chance to watch them as they came down. The height was 80 feet," via the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Memorial.

Rescue attempts were ineffectual

According to the Village Alliance, a passerby on Washington Place noticed the smoke and sent out the first fire alarm just before 5 p.m. Pure pandemonium greeted the rescue workers who arrived on the scene to put out the fire. Company 20 were the first on the scene, but the firefighters were woefully unprepared to deal with the magnitude of the blaze. Initially, they had difficulty even reaching the building, due to the bodies of jumpers that covered the surrounding sidewalks.

When they finally did get close enough to the factory, it became apparent their hoses were not strong enough to be effective against the flames. The water pressure was too weak to reach the eighth floor, rendering them essentially useless, according to Baruch College. The ladders were also too short, reaching only as high as the sixth floor.

Unable to reach the workers on the top floors, rescue workers laid out nets to catch the jumpers. However, multiple people lept from the buildings at once, and the nets were not strong enough to bear their weight. The life nets ripped, sending more people to their deaths, according to the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Memorial. Ill-equipped and overwhelmed, Company 20 had to send out four more alarms before they finally go the inferno under control.

'Too much blood has been spilled'

The entire fire lasted just 15 minutes. In that short time, 146 workers died, per the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Memorial. The structural integrity of the building remained intact, but the human devastation was unprecedented. The Triangle Shirtwaist factory fire was the deadliest industrial accident in the history of New York City, and remained so until the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001, per OSHA. The loss was so great, makeshift morgues had to be set up to house the dead. Families struggled to identify their relatives, many of whom were burned so badly they were unrecognizable. Six victims remained unidentified until 2011, per Britannica.

The International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union declared a day of mourning, per Cornell University. The week following the fire, 350,000 people joined in the Triangle victims' funeral march, and crowds of people attended a memorial meeting hosted at the Metropolitan Opera House, per AFL-CIO.

At the Metropolitan Opera House, labor activist Rose Schneiderman delivered a passionate call to action, declaring "the life of men and women is so cheap and property is so sacred. There are so many of us for one job it matters little if 146 of us are burned to death... Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement," via the Jewish Women's Archive.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory owners were indicted for manslaughter

The public was outraged, and they demanded someone be held accountable for the many preventable deaths that had occurred in the factory. On April 11, 1911, the Triangle Factory owners, Harris and Blanck, were indicted on seven counts of first and second degree manslaughter, per PBS. Their trial began in December 1911. The prosecutor, Charles Bostwick, charged the owners had broken section 80 of the Labor Code, which mandated factory doors remain unlocked, by knowingly locking the exit doors near closing time.

Harris and Blanck had hired a prominent defense attorney named Max Steuer, who immediately began to poke holes in witness' testimonies. Over 100 witnesses testified, and Steuer focused on destroying their credibility by claiming the prosecutors had told them in advance what to say on the stand. Kate Alterman, a survivor of the fire, was made to repeat her testimony multiple times. Steuer seized on the fact her phrasing remained the same throughout, claiming this proved she was simply reciting a memorized statement, per the Village Alliance.

After three weeks, the jury, unable to prove Harris and Blanck knew the doors were locked, acquitted them of all charges. They were eventually ordered to pay out about $75 per victim, after losing a civil suit in 1914, per Forbes. However, their fire insurance payout was $60,000, which amounted to more than $400 per victim, leaving them still comfortably in the black.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire sparked a series of labor reforms

The Triangle Factory fire was far from unique. A similar fire had occurred at the Wolf Muslin Undergarment Company factory in Newark, New Jersey the previous year, but it failed to stir the public into action, per the New York Times. The Triangle Factory fire, however, became a touchstone which workers and activists, led by the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union, rallied around, calling for immediate labor reform.

Politicians began to pay attention, and on June 30th, 1911, the New York State Legislature established the Factory Investigating Commission. Per the Village Alliance, the goal of the commission was to "investigate factory conditions in this and other cities and to report remedial measures of legislation to prevent hazard or loss of life among employees through fire, unsanitary conditions, and occupational diseases."

The commission gathered testimony and performed factory inspections. By the end of 1911, they proposed 15 new fire safety laws and passed eight, per Smithsonian Magazine. New York City also established the Bureau of Fire Investigation, which empowered the fire department to improve worker safety and eventually led to the passing of 38 new labor regulation laws. These laws included mandatory safe fire exits, on-site fire extinguishers, installation of alarm and sprinkler systems, and even a reduction in working hours, per the Village Alliance. In addition, New York City founded the American Society of Safety Engineers in October 1911.

'They did not die in vain'

The labor reform movement that emerged in the wake of the Triangle Factory fire influenced politics for decades to come. Progressive politicians became champions of the labor movement, working hand in hand with organized labor to reform working conditions, both in New York City and on a national level.

Twenty years later, many of the same politicians who helped spearhead labor reform in the wake of the Triangle Factory fire would join President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal. The progressive group included New York Governor Alfred E. Smith, and Robert F. Wagner, the director of the Bureau of Fire Investigation, who would later become a main New Deal legislator and strong labor movement supporter, according to History.

Most notably, Frances Perkins, who helped to establish the Factory Investigating Commission in 1911, went on to become the New York State Commissioner of Labor in 1929, before becoming the first woman to serve in a federal cabinet position. In 1933, she was appointed President Roosevelt's Secretary of Labor. Perkins herself saw a direct link between the activism sparked in 1911 and the New Deal. In the Triangle fire's 50th anniversary memorial speech, she declared "They did not die in vain, and we will never forget them," via the NY Department of Labor.