The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Emily Dickinson

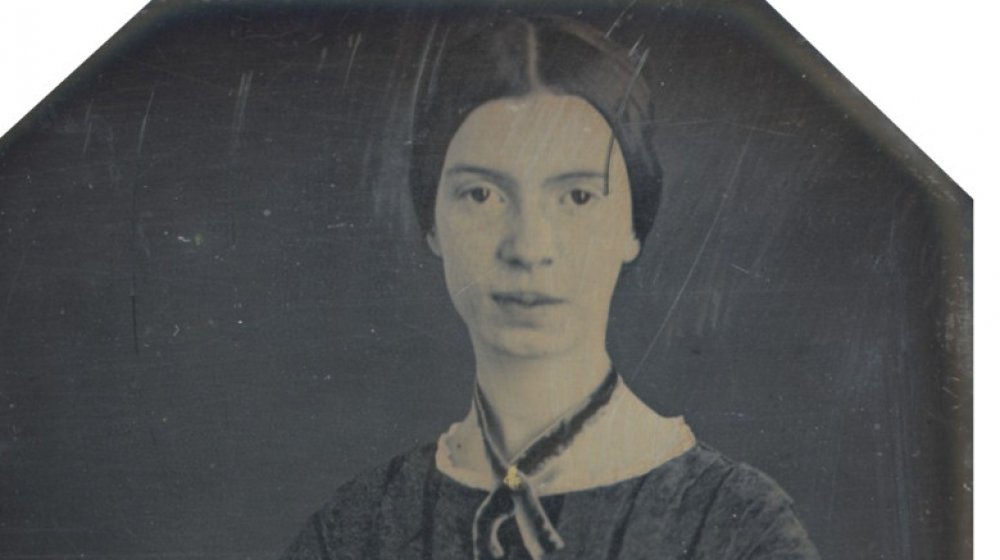

Today, Emily Dickinson is one of the most famous American poets, whose work you almost certainly encountered at some point in your school years. Dickinson was a trailblazer in poetry, incorporating an intimacy and immediacy to her poetic voice that was wholly new and exciting, conflating personal and inscrutable interior desires and memories with universal imagery that made them seem shared, like secrets between friends. You might not always understand what Dickinson was specifically thinking of when composing a poem, but you always feel like it speaks to something you have experienced yourself.

All great literature stems from the life experience of the artist, their emotional journey, and their interpretation of events. In Dickinson's poetry, you get a sense of who she was as a person: intelligent, curious — and sad. If all you know about Dickinson is that she existed and that you can sing all of her poems to the tune of the Gilligan's Island Theme Song, you might not know that her poetry's rich emotional palette stems from a life filled with sadness and loss. Read about the tragic real-life story of Emily Dickinson, and her poetry will have a new depth and meaning.

Emily Dickinson probably suffered from epilepsy

If Emily Dickinson's poetry hadn't been published after her death, she might have remained little more than a local legend. Born into a prominent family in Amherst, Massachusetts, she never left her family home and was referred to as "The Myth" or "The Lady in White" around town. Although obviously intelligent and enjoying many close relationships throughout her life, Dickinson was considered at the time to be a classic spinster — a woman who never married — and, later in life, a recluse.

She was also frequently unwell, suffering at different times in her life from respiratory illnesses and troubles with her eyesight. But author Lyndall Gordon writes in The Guardian that there is evidence Dickinson suffered from another lifelong affliction: epilepsy.

Gordon notes the near-constant reference to illness and the brain in her poetry, and the prescriptions written for her by her family physician are in line with 19th-century treatments of what was then called the Falling Disease. This would also explain Dickinson's frequent absences from school as a child — and her reclusive nature. At the time, epilepsy was still widely misunderstood, and epileptics were often considered to be evil, violent, or otherwise impaired. If a member of a prominent family suffered from the ailment, they would be very likely to try their best to conceal it — which might require that they stay inside, hiding.

Emily Dickinson loved a woman

Emily Dickinson's love life is a fascinating subject. For a woman who was reclusive and socially isolated, her poems brim with passion and references to mysterious objects of her affection, and as The Rumpus notes, she wrote — though possibly never sent — three infamous (and steamy) letters to an unknown person she referred to as her "Master." She forged several very deep relationships with men over the course of her life, but there is another, even more tragic possibility: that Emily Dickinson was in love with a woman at a time when such relationships were beyond impossible.

Author Martha Nell Smith writes that Dickinson's unusually close relationship with her sister-in-law, Susan Huntington Dickinson, was very likely a romantic one. They lived next door to each other and wore a deep path between the houses with their frequent visits, and they enjoyed an intense correspondence of letters and passed notes that writer Maria Popova describes as "electric love letters" and The New York Times describes as having "an intensity that some might view as erotic."

It's impossible to know whether Emily and Susan truly had a romantic relationship, but the circumstantial evidence is compelling. If it's true, they would have had to keep their relationship secret from everyone, especially Susan's husband — Dickinson's own brother.

Emily Dickinson remained anonymous

The world simply wasn't ready for Emily Dickinson's unique brand of poetry, and she actually made very little formal effort to publish her work. The level of interest she had in traditional publication is open to debate, but as The New Yorker writes, her disinterest in official publication doesn't mean she didn't want her poetry to be read (her deathbed order to burn her poems aside). She sent many poems to friends, for example, and even tried her hand at self-publishing with hand-bound collections. She produced 40 such books during her life.

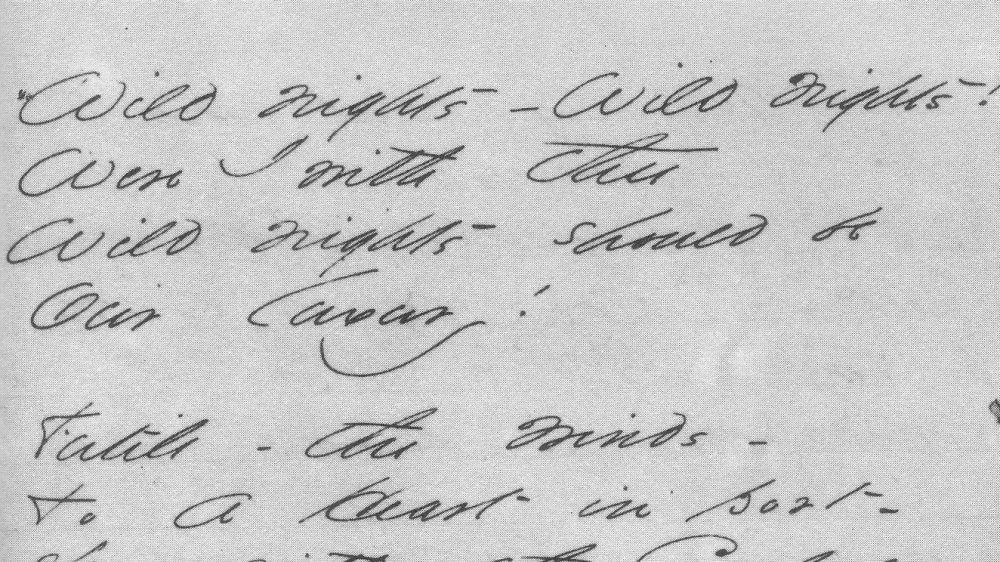

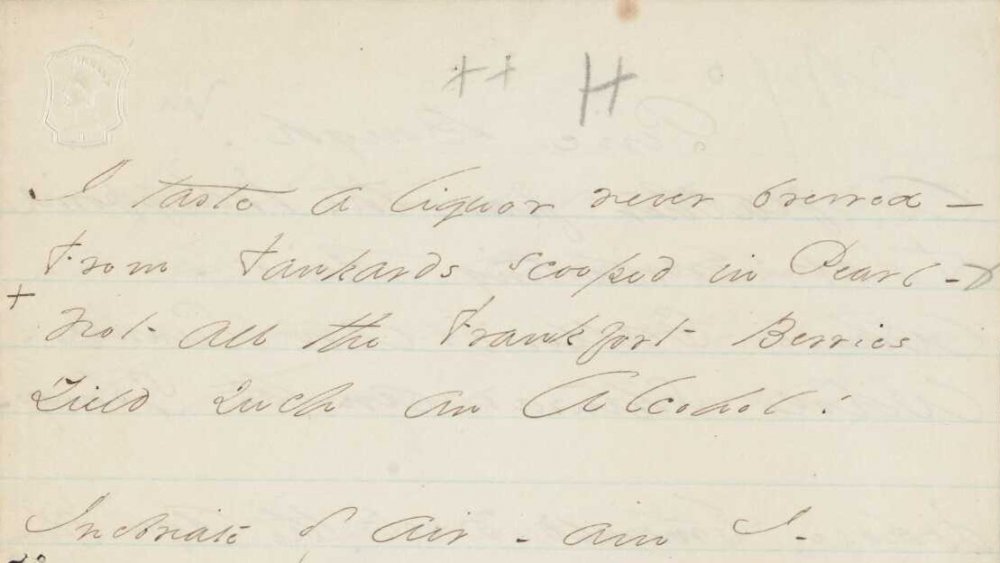

The tragedy is that Dickinson died without recognition for her work. Only ten of the nearly 1,800 poems she wrote were published in her lifetime, and those were published anonymously and were heavily edited in ways that removed everything that made them hers — including giving them titles and rhyme schemes that turned them into prettier but less interesting works. For example, Dickinson scholar Thomas H. Johnson notes that her poem "I taste a liquor never brewed" was printed in The Republican in 1861, but the editor gave it a different title and introduced a traditional rhyme scheme to replace Dickinson's more sophisticated "slant" rhyme. Nothing could be more depressing to a writer than to see their work so fundamentally changed, which might explain her disinterest in publication.

Emily Dickinson Lost Carlo

Emily Dickinson understood the fundamental truth of life: We simply don't deserve dogs. As professor of American literature Colleen Glenney Boggs writes, Dickinson was given a puppy by her father in 1849 and named the dog Carlo after a dog mentioned in the novel Jane Eyre. (Boggs also notes that "Carlo" was a very common name for a pet dog in the 19th century.)

Dickinson and Carlo became best friends for the next 16 years. The Academy of American Poets reports that beginning in 1850, you can find references to Carlo in many of Dickinson's letters and even her poems. In her letters, Dickinson described Carlo as being almost as large as she was, and in her poetry, she refers to Carlo with obvious affection and loyalty. As anyone who has ever enjoyed a dog's faithful companionship knows, losing such a friend can be a terrible emotional blow, and it's likely no coincidence that when Carlo passed away in 1866, Dickinson withdrew even further from outside life.

Despite her obvious pleasure in the animal and her tendency to refer to him in her work, Dickinson never took another pet despite living another two decades. As Wendy Martin, a professor of American literature, writes, Dickinson penned a poem in Carlo's honor: "Time is a test of trouble / But not a remedy — / If such it prove, it prove too / There was no malady."

Emily Dickinson had a strained relationship with her mother

Emily Dickinson is commonly known to have been a recluse, a woman who never moved out of her childhood home and who rarely even went outside. She wasn't the first Dickinson woman to behave like that, however. Her mother, who she was named after, also rarely left the house — but there was a crucial difference between the two. Where Emily was intensely emotional in her poetry and lavished affection on her friends, Harvard Magazine describes her mother as "quite aloof," a woman who suffered from a mysterious illness for most of her life.

Emily herself had few kind words for her mother. Journalist Esther Lombardi notes some of the things she wrote about her mother in letters, including "My Mother does not care for thought" and "Could you tell me what home is. I never had a mother."

There is speculation that her mother suffered from depression or even bipolar disorder, explaining her lack of affect and disinterest in her daughter's well-being. This strained relationship was made even more difficult for Emily when her mother suffered a stroke and broken hip and was bedridden for the last seven years of her life, depending on Emily and her sister Lavinia to care for her until the end.

Emily Dickinson's closest friends died young

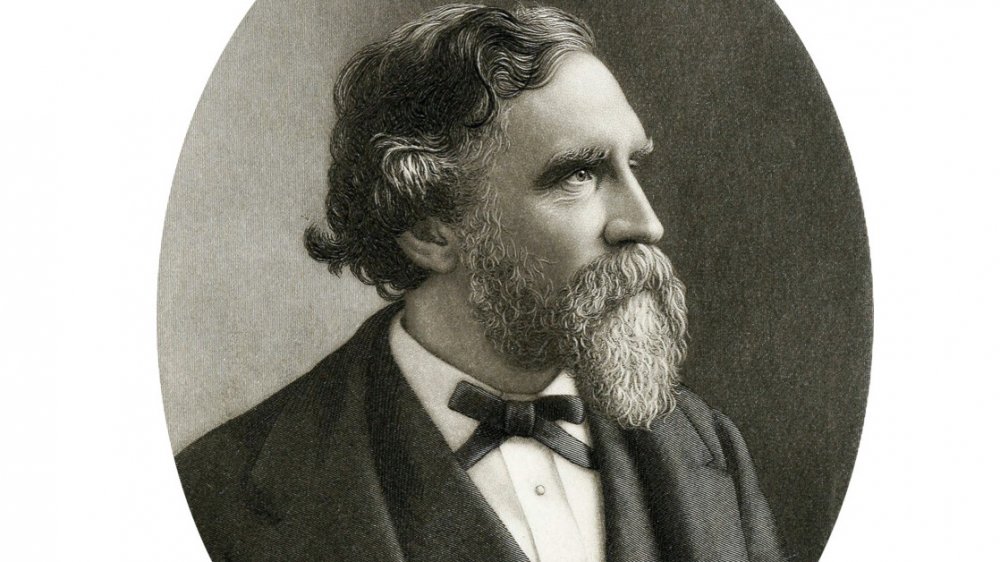

For a reclusive woman who hardly left her house and never traveled or married, Dickinson had no shortage of intense relationships. Two of the most important were with the Reverend Charles Wadsworth and Samuel Bowles. As academic Thomas H. Johnson wrote in American Heritage Magazine, there is plenty of evidence that Dickinson was absolutely in love with Wadsworth — though she only met him in person twice, and the pious reverend showed no signs of returning the sentiment beyond a platonic affection. And as The New Yorker notes, when Dickinson entered into her most reclusive phase, it wasn't that she saw nobody, it was that she only saw an exclusive list of people, one of whom was Samuel Bowles (pictured above).

Her attachment to Wadsworth was obviously very deep: When he moved to San Francisco to join the Calvary Church, Johnson notes that the word "Cavalry" begins to appear in Dickinson's poetry, and no other place name is used nearly as often in her work.

Bowles died in 1878 when he was just 52 years old, and Dickinson wrote to his widow expressing her deep sadness at his passing. Wadsworth passed away just a few years later, in 1882, and Dickinson mourned, calling him "my dearest earthly friend." Most tragically, these were just the two most prominent friends that Dickinson lost in the last years of her life.

Emily Dickinson's lover died

Emily Dickinson's love life is an endless source of speculation precisely because of her spinsterish image — and its contrast with the fiery emotions of her poetry. When her father died in 1874, his old friend Otis Lord, a judge on the Massachusetts Supreme Court, maintained his interest in the family — especially Emily. He visited often and asked Emily's sister Lavinia to report on her health to him. When Lord's own wife passed away a few years later, this friendship erupted into a completely inappropriate love affair of sorts.

As author Lyndall Gordon writes, not only did Lord's own family fully believe rumors that Emily's sister-in-law had walked in on her embracing Otis in a more-than-friendly fashion (they referred to her as "Little Hussy"), but Dickinson's letters to Lord are practically confessions to the affair, such as one that says, "lift me back, wont you, for only there [in your arms] I ask to be." Meanwhile, Judge Lord's visits to Amherst became so regular that the locals began to openly speculate about a wedding despite him being 18 years older than her.

Tragedy struck before anything could come of it. Lord suffered a debilitating stroke in 1882, leaving him largely incapacitated, and he died two years later, possibly robbing Dickinson of her last chance at love and marriage.

Emily Dickinson died young

Part of the tragedy of Emily Dickinson is that she died so young. After a lifetime of isolation and illness, she passed away in 1886 at the age of just 55. Worse, her last years were marked by steady loss of friends and family, losses that sapped her desire to leave the house or even to write and circulate the poetry that had been her lifelong passion.

As Alfred Habegger writes for Encyclopedia Britannica, Dickinson's cause of death was a stroke, which her doctors attributed at the time to Bright's Disease, an affliction of the kidneys. Modern-day doctors have speculated it might have actually been hypertension. But author John Evangelist Walsh writes that it might have been much sadder than that: Emily Dickinson may have committed suicide.

Walsh's case is circumstantial but persuasive. Dickinson was clearly depressed after the loss of several loved ones, including Otis Lord, a man many speculated she might marry. She'd become almost totally reclusive in her last years, never leaving the house, and she'd stopped sending out her poems — though she continued to write, and her poetry from this period is dark, focused on death, and makes many references to famous suicides. Finally, the symptoms she exhibited in her final hours are in line with poisoning, indicating that she may have decided the time was right and taken things into her own hands. After all, this was the woman who wrote the famous lines "Because I could not stop for Death / He kindly stopped for me."

Emily Dickinson was only recognized after she died

Today, Emily Dickinson is a famous poet. Her poetry is studied, reprinted, and enjoyed by millions around the world. One of the most tragic aspects of her life is the fact that she died unrecognized for the genius she was.

When Dickinson died in 1886, no one outside of her immediate circle was aware of her poetry — and even they didn't have any idea of the scale of her creativity. She had asked her sister Lavinia to burn her papers, but when Lavinia discovered almost 1,800 poems in Dickinson's rooms, she thankfully decided that the word "papers" didn't mean "poems" and that the world needed to see her sister's work. The subsequent publishing of those poems finally woke the world up to Dickinson's genius.

But as Literary Hub reports, there was one further tragedy inflicted on Dickinson: The process of editing and publishing her poems was handled by a woman named Mabel Loomis Todd — who had engaged in an explosive extramarital affair with Dickinson's brother, Austin. Mabel took the work seriously but faced challenges: Dickinson's handwriting, for one, which she found difficult to parse. Another was the fact that Dickinson often worked outside of traditional forms, using techniques that are quite common in poetry today but were unusual back then. Todd often substituted words and changed rhyme schemes to make the poems more readable — but losing some of their genius in the process.

The death of Emily Dickinson's nephew broke her

Emily Dickinson's final years were marked by a series of personal losses. A woman with a very small social world, she watched helplessly as old friends vanished from her life. But one death appears to have been the final straw for the poet: Her young nephew Thomas Gilbert "Gib" Dickinson.

Gib died of typhoid in 1883. Author Sharon Leiter writes that he was a "remarkable" boy who was much-loved by his parents and everyone around him — especially his Aunt Emily, who doted on him and often took part in his adventures. When Gib fell ill with typhoid at the age of eight and lay on his deathbed, something remarkable happened: Emily, who had not been to her brother's house in 15 years (and who barely left her home at all) went there to sit with the young boy.

Dickinson fell ill after Gib's death and never fully recovered. She ceased most of her usual activities, including writing and sending out her poems to friends and family, and died just a little more than two years later. While there's no way to know for sure, her actions in these final years seem like a woman who was broken by this final, terrible loss.

Emily Dickinson spent her last year a recluse

Emily Dickinson was never much of a traveler – Time Magazine refers to her as a "textbook recluse." She was introverted and reclusive even in her youth, and The New Yorker reports that she was known as "The Myth" by residents of Amherst, who were well-aware that she hardly ever left her home and engaged in curious behaviors like speaking to people through closed doors and lowering things in baskets from windows rather than coming down to interact with people.

Dickinson's eccentric ways soured into something worse in her final years, however, as she lost most of the important people in her life, including her lover Otis Lord and her close friends Charles Wadsworth, Helen Hunt Jackson, and Samuel Bowles. As Alfred Habegger writes for Encyclopedia Britannica, "The deaths of Dickinson's friends in her last years [...] left her feeling terminally alone." After the death of her beloved nephew, Gib, in 1883, Dickinson went beyond her usual isolation and retreated into her home, never to emerge again, for any reason. She spent the final year of her life almost totally and voluntarily cut off from the rest of the world, seeing almost no one.

Emily Dickinson gave up on her poetry

The most tragic thing any artist can do is to give up on their art — to stop creating and sharing their work with the world. This is precisely what Emily Dickinson did in her final years.

How much Dickinson wanted to publish her work is up for debate. Although only about ten of her poems appeared in print while she was alive — anonymously, sometimes apparently without her direct involvement — she also sent her poems to many of her friends and, as rare bookseller Debbie Deegan notes, assembled her poems into carefully edited and arranged hand-bound books.

But in her later years, Dickinson stopped making these books. As the Emily Dickinson Museum writes, poems from her final years appear on scraps of paper, as if they were afterthoughts. Even more tellingly, when she instructed her sister Lavinia to burn her "papers" after her death, she left no specific instruction for the dozens of poetry books she left behind — leaving open the possibility that she included her poems in that request and intended to erase them from the world when she was gone.

Luckily for us, Lavinia didn't listen. She burned Dickinson's personal letters as instructed — but opted to publish the poems.