The Most Brazen Propaganda Campaigns Ever

As long as language has existed, so has propaganda: the use of information — usually misleading, if not totally false — to persuade and manipulate (the scientific term is bamboozle). Most of us like to imagine that we're too smart to fall for propaganda, but the truth is most propaganda is subtle and omnipresent, and the best of it actually incepts you and makes you think it was your idea all along. From political messaging to commercials and advertising, propaganda is literally magic: An attempt to change reality using nothing more than words and human psychology.

And then there are examples of propaganda that took a big swing—misinformation campaigns that didn't bother with subtlety and might as well have had a big bright disclaimer reading "THIS IS PROPAGANDA." The fact that most of these examples were successful to a large extent despite being the most brazen propaganda campaigns ever is a testament to the power that propaganda has when it's used skillfully. It should serve as a warning to us all: You might think you're immune to propaganda, but you probably aren't.

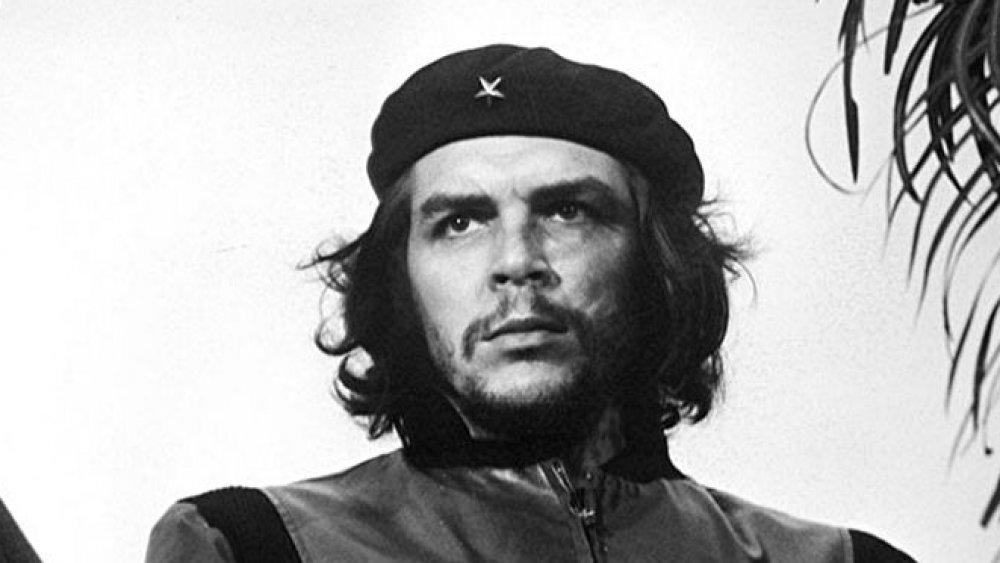

'Guerrillero Heroico' was great PR for Che Guevara

Che Guevara is one of the most complex figures in recent history. Born to a well-off middle-class family in Argentina, he became a doctor and embarked on lengthy motorcycle journeys around South America. These epic road trips exposed the already-politically aware Guevara to lifestyles and political beliefs he might otherwise have missed. This put him on a path towards an increasingly radical viewpoint that led him to the Castro brothers and the Cuban revolution, where he eventually rose to second-in-command behind Fidel.

Opinion on Guevara remains hotly divided. Some regard him as a champion of freedom. Others note his violence and cruelty and regard him as a criminal. (History reports that while he was in charge of La Cabaña prison, he personally ordered 144 people executed). None of this matters, though, because of one of the most blatant pieces of propaganda ever produced: Guerrillero Heroico, the iconic photo of Guevara that NPR notes has become the most-reproduced photo in history.

As Smithsonian reports, the photo, taken by Alberto Korda in 1960, has become so ubiquitous it's been adopted by just about any movement or philosophy that considers itself countercultural—or that just wants a cool, edgy icon. The result of this brazen effort to make Guevara look the part of the heroic and determined revolutionary is that his image and identity has become divorced from his actual beliefs and actions. His face is now just a generic image for rebellion.

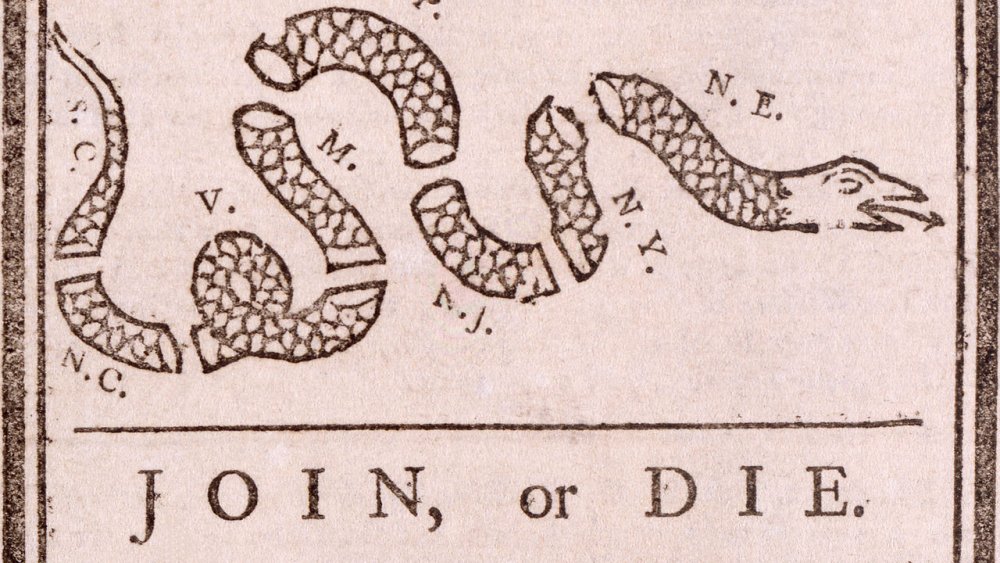

'Join, or Die' helped create the United States

One of the most famous icons of the Revolutionary War is the "Join, or Die" illustration created by Benjamin Franklin. Depicting a snake divided into eight pieces representing the British colonies in America (South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania are labeled specifically, with the four New England colonies grouped together under the label "N.E."), it's a powerful message made even more effective due to its brevity and simplicity.

It's such a powerful piece of propaganda, in fact, it was used twice. As author Karen Severud Cook writes, Franklin originally published the illustration in his newspaper The Pennsylvania Gazette in 1754 in an effort to unite the colonies against the French during the French and Indian War. As Cook notes, the genius of the illustration is that the superficial simplicity hides a much deeper message. Resembling a map, the snake's undulations mirror the curves of the eastern coastline, evoking the image of a united set of colonies.

A decade later, the drawing was recycled against Franklin's wishes and re-purposed to promote unity between the colonies against the British. The Constitution Daily notes that it employs one of the key features of propaganda very powerfully: Fear. Propaganda often tries to persuade people that they are in danger unless they do as the propaganda says, and there's nothing scarier than being told you will flat-out die if you don't follow old Ben's advice.

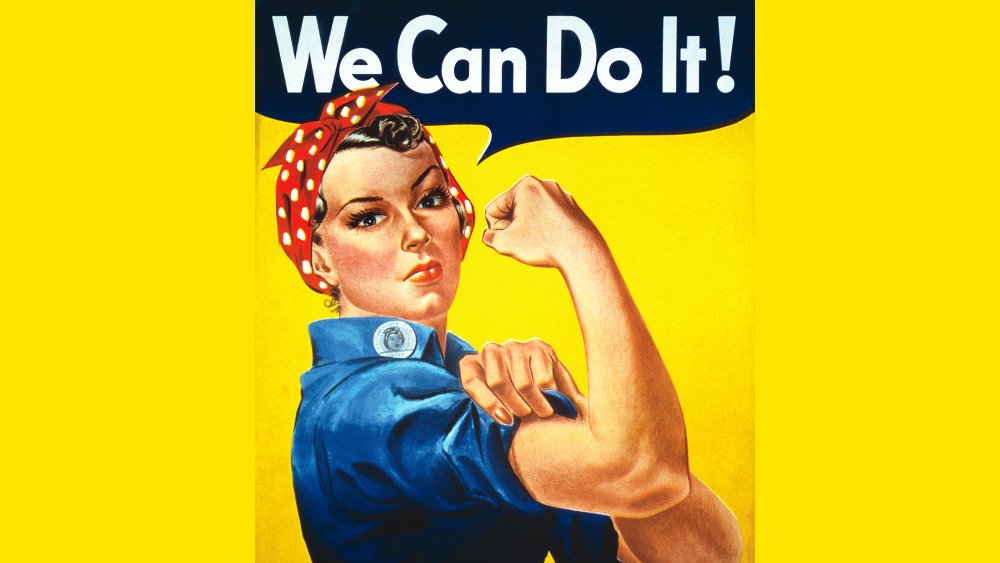

Rosie the Riveter certainly did it

Propaganda's main purpose is to manipulate, typically using misleading or outright false information and imagery. So it's fitting that according to The Atlantic the model who inspired the famous "We Can Do It!" poster, known now as Rosie the Riveter, only actually worked her World War II factory job for two weeks before quitting out of fear of an accident, despite encouraging others to pitch in.

With most able-bodied men off to war in the 1940s, the U.S. needed women to step up and take over the manufacturing jobs they'd left behind. Posters like this one were designed to make it acceptable and patriotic for women to take on a traditionally male job. Except, most of the 18 million women who took that challenge weren't new to the workforce—many had lost their jobs during The Great Depression, and others already worked in lower-paying jobs, so this wasn't the mind-blowing gender flip it was portrayed to be.

Worse, as soon as the war began winding down the government shifted gears and encouraged those women to leave those jobs so that the weary soldiers returning home could take them, leaving many women feeling a bit betrayed. So it's also fitting that, as Fast Company reports, the feminist movements of the 1970s and 1980s appropriated Rosie, once again using her image to inspire and manipulate opinion, thought this time with slightly purer motives.

America's Army was propaganda for the real one

Military service is a noble and sometimes necessary choice, and millions of Americans make a career out of that service. But it's also an extremely dangerous job that shouldn't be made into a game—which is exactly what America's Army does.

What's America's Army? According to TechRadar, it's a first-person shooter video game that the United States government spent nearly 33 million tax dollars developing. Originally released in 2002, it's gone through several updates, with the most recent arriving in 2013. It's also clearly some pretty blatant propaganda, explicitly making serving in the United States Army seem like a lot of exciting fun while simultaneously grooming young folks to be better prepared for basic training should they follow through and actually join up. As reported by HowStuffWorks, the government takes the game seriously enough to test conceptual weapons in it.

This kind of recruitment could be vital for the future of military operations. As The Guardian reports, the increasing use of drones and other remote technologies in warfare has made video games like America's Army increasingly useful, with some recruits considering their training to have begun long before they actually joined up—playing said video games. It might be brazen propaganda, but that doesn't mean it's not working: As TechRadar points out, studies have shown that Americans aged 16 to 24 have a more positive view of the army because of video games like this.

'La Bestia' is dangerously catchy propaganda

Immigration has been a hot-button topic in the United States for decades, and we're all familiar with some of the efforts (like a big, beautiful wall) to curtail the illegal movement of people from Mexico, Latin and South America into the U.S. But the U.S. isn't just relying on walls and patrols to keep people out. There's also plenty of good, old-fashioned propaganda—including a really catchy song that was released a few years ago.

As reported by The Guardian, "La Bestia" ("The Beast") is a song about the dangers of hopping on the big freight trains many desperate immigrants ride northward. The trains are often referred to as The Beast or the Train of Death anyway, so the song's title isn't exactly subtle. With lyrics like "They call her the Beast from the South, this wretched train of death/With the devil in the boiler, whistles, roars, twists and turns" the song might seem like an unlikely radio hit—until you realize that, as Vice reports, the song was created and distributed by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Agency.

According to the songwriters, Carlo Nicolau and Eddie Ganz, the song was part of a compilation CD that was sent out to radio stations throughout Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, and other areas without any sort of heavy-handed messaging. As with the most effective propaganda, the hope is that the song penetrates popular culture and makes people more afraid of riding the big freight trains northward.

North Korea is almost nothing but propaganda

What do you do when you're a poor, isolated nation in need of an image revamp? According to Business Insider, if you're North Korea between the years 1969 and 1997 you buy a series of expensive full-page advertisements in newspapers like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Guardian. And since this is North Korea, those advertisements were both a little crazy and incredibly ineffective.

The problem was that the propaganda aspect was too obvious. Since North Korea couldn't get the major Western press to take them very seriously, they tried to play a game where they purchased ads that were made to look like articles in, say, The New York Times, then turn around and claim the newspaper had reported the content of the ads. The whole idea was to convince North Koreans at home that their country wasn't a failed state. For example, an advertisement placed in The New York Times in 1969 promoted an English-language biography of North Korea's then-leader Kim Il-Sung. When this was reported to the North Korean people, they were told it was a piece of journalism that appeared "under the block-letter title, 'Korea Has Produced the Hero of the 20th Century.'"

But as NK News notes, even North Korea's supporters thought this was a dumb idea, since the ads had little effect and were extremely expensive.

Russian troll farms did their job

Russia is certainly no stranger to the joys of propaganda, and has perfected the use of modern-day technology and social media to get the job done. The New York Times reported on Russian "troll farms" that employ people to spread disinformation and chaos while posing as ordinary Internet users, describing a complex attempt at a disruptive hoax aimed at a small parish in Louisiana in 2014. What's remarkable about these efforts is that they don't have a single, clearly-defined goal like traditional propaganda—they're designed to destabilize in general and to erode our trust in sources of information and authority.

And it's pretty brazen. As The Guardian reports, people employed at the St. Petersburg building where most of these troll farms operated created multiple accounts on social media platforms, pretending to be locals, and actually posted tons of benign, normal Internet-type stuff like recipes and sharing songs they liked in an effort to build up a realistic presence while sifting in more politically-charged propaganda.

Trolls with good English-language skills are also directed to comment on articles published by The New York Times and other news sources, causing even more chaos. And the folks who orchestrate online hoaxes like the one in Louisiana operated under the moniker "Special Projects Department." What makes this propaganda so effective is how hard it is to tell real people from fake when everything is online.

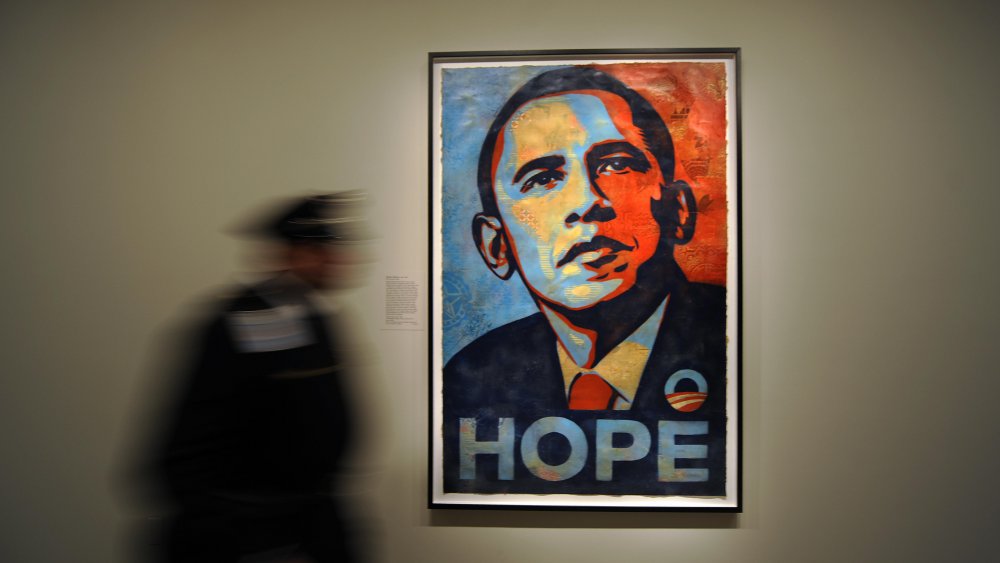

Obama's Hope was subtler propaganda

The word "propaganda" has a negative connotation, of course, and so we tend to only apply it to material promoting something we disagree with or consider evil. A lot of people don't think of the famous Barack Obama "Hope" poster created by Shepard Fairey to be propaganda—but it certainly was. And it didn't make any effort to hide the fact.

In an interview in The Huffington Post, in fact, Fairey said he waited to get formal permission from Obama's team before proceeding because he "didn't want to act without permission and have it be seen as undermining Obama's goals in any way." Once he had that permission, he created the image in just one day. The original poster used the word "Progress," but the campaign thought this was a little off-message, and so it was changed to "Hope." The colors Fairey chose evoke the American flag without being too literal, and the blocky, graphic style of the image makes it both easily reproducible in any format as well as visually interesting.

It worked like gangbusters, of course. Fast Company notes that the poster now resides in the National Portrait Gallery, and it's so iconic there have been countless riffs on it—the color scheme alone is so unique you know precisely what's being referenced even if every other detail is different.

Operation Himmler

In 1939, Hitler and the Nazis had a problem. After convincing many of the German people that all their post-World War I woes stemmed from the terrible treaty Germany signed at Versailles, and promising that re-activating the military and becoming "strong" again would fix everything, they needed to make some moves to prove the theory—but without appearing to be the aggressor. In other words, Hitler wanted to invade Poland but wanted it to look like self-defense, which was problematic since the Poles didn't have much of an army and weren't intending Germany any harm.

The answer was one of the most transparent propaganda efforts of the 20th century, Operation Himmler. As The Washington Post reports, Germany staged an attack by Polish soldiers on a radio station. According to The Atlantic, this was actually a pretty fancy affair with soldiers wearing Polish uniforms who broke into the station and broadcast anti-German statements. Western journalists were then brought in and shown fresh corpses—prisoners recently executed—and told that this was evidence of Polish brutality. Hitler then went before the Reichstag and made a fiery speech against the Poles, kind of ignoring the fact that Germany had signed a nonaggression treaty with Poland five years before, and that Poland's military mobilization was slow and incompetent. Two days later World War II started, so Operation Himmler was a ... success?

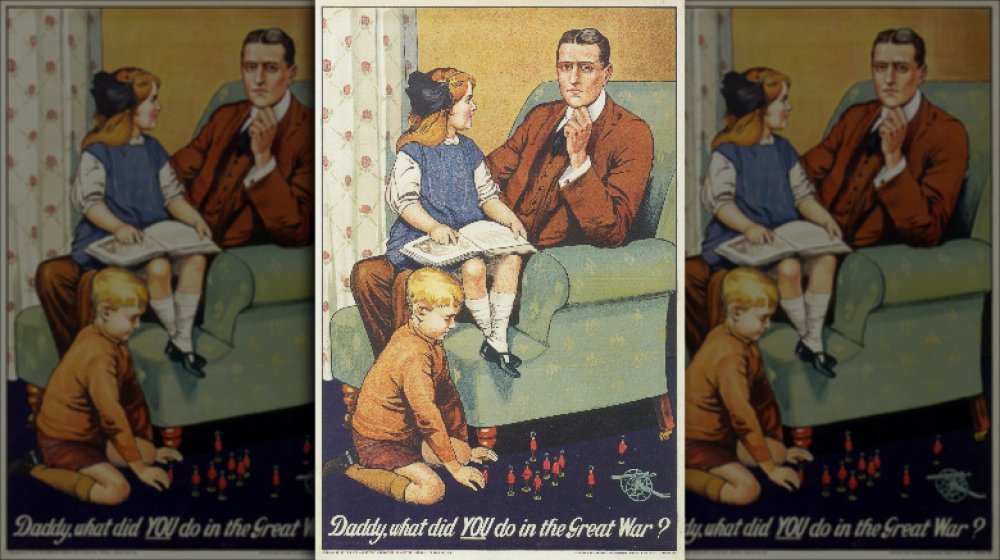

'What Did YOU do?'

Propaganda doesn't necessarily need to rely on false facts to be effective. Sometimes plain old-fashioned emotional manipulation is all it takes. Back in 1916 the British War Office devised one of the most obvious attempts to shame men into joining the army the world has ever seen: The "Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?" poster.

When World War I broke out, Britain—like most countries—wasn't quite prepared. As the British Library notes when discussing the poster, Britain's army was small, there was no draft in place, and many men worried the pay cut they would take to join the army would leave their families destitute. In order to convince men to volunteer for military service, Britain turned to the burning power of shame, brilliantly using that same sense of familial duty against them with a poster that forced them to contemplate how they could possibly seem like anything but a coward when trying to explain their decision to their children.

It's a brilliant piece of psychology—the man's expression of empty horror when his daughter asks this simple question is incredibly bleak. It's an expression no one ever wants to wear on their face. It's such a powerful idea that it works even though you know you are being manipulated.

Soviets were the original Photoshop

Stalin was good at a lot of things. Murdering people, for instance. Also, running a huge country thoroughly into the ground. But his greatest skill was changing history, typically through the simple expedient of erasing people from photographs.

In fact, as The New Yorker writes, Stalin didn't just order people removed from photos, he often had people inserted into photos—most notably himself. Stalin was very sensitive about his lack of active participation in the revolution that brought the Bolsheviks to power, and his way of dealing with it was to erase people like Leon Trotsky (who he eventually managed to erase in real life) from photos and then have himself pasted into others. As Open Culture notes, many of these manipulations were designed to present Stalin as the sole hero of the Soviet Union.

The end result was clumsy, obvious propaganda, but it did the job. Not only did these photographic alterations remove any evidence that history and reality were different than what Stalin said they were, they also served as very obvious warnings to people regarding the fate of folks who ran afoul of Stalin. As The New Yorker points out, there are many photos from Stalin's reign of terror where it's obvious someone has been erased—but we don't know who.

The 2008 Summer Olympics made China look good

Propaganda usually employs some razzle-dazzle in order to get past your defenses and sink into your brain. Back in 2008, the People's Republic of China, looking to leave behind its image as a totalitarian state that drove tanks over protesters and reset itself as a thriving and peaceful economic powerhouse, used more razzle-dazzle than was previously thought to even exist in the universe. The propaganda? The 2008 Summer Olympics opening ceremonies.

As The New York Times notes, all Olympic opening ceremonies are essentially propaganda for the host country, but in 2008 China seemed to be determined to blow minds worldwide. Choreographed by filmmaker Zhang Yimou, it was perhaps the most spectacular opening ceremony ever. And despite the very, very obvious and blatant intention of the ceremony, it worked, making China look like a cheerfully prosperous country of dancing, singing, happy people.

A Reuters article, however, peeled back the illusion slightly, noting that while many of the blandly positive, building-sized posters around Beijing were written in many languages, smaller signs aimed at Chinese speakers were bluntly ordering citizens to "not be filthy" and to "obey regulations." And many of those huge signs were actually covering up half-finished construction projects the Chinese were worried would make them look poor and incompetent. Good thing they had all those fireworks to distract us.