The Untold Truth Of General Custer

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

General George Armstrong Custer remains a household name as the man who died at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876. The legendary massacre, in which Custer and over 200 other soldiers died along the Little Bighorn River in Montana, remains one of the most controversial engagements in history. Some historians assert that Custer foolishly led his men to certain death even after he'd been warned that he was outnumbered, according to Our Great American Heritage. Others revere him as one of the best leaders of his time. Either way, Custer's Last Stand remains on the books as the "worst American military disaster ever," as stated by Eyewitness to History.

But there's more to the controversial Custer than meets the eye. He was, states We Are the Mighty, a dedicated Civil War soldier who was deemed a national hero after the Battle of Gettysburg. He has been called brave, brash, and a dedicated husband — but also a devout narcissist who made rash decisions and whose men couldn't stand him. In all, it took only 15 years after Custer graduated from West Point to get himself killed at Little Bighorn. In between, the seemingly charmed man led a life that remains worthy of note, if only because he was about the craziest commander of the early West. Read on for some little-known facts about the historic figure America loves to hate.

Custer almost chose a career as a teacher

According to American National Biography, George Armstrong Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio, in 1839, to farmers Emanuel and Maria (nee Ward) Custer. History confirms that as a young child, George was unable to pronounce his middle name, calling himself "Autie." He would carry the nickname throughout his life. The Custers were a large, "rough-and-tumble" family, and Autie spent his youth running around the countryside hunting and fishing and was big on practical jokes. As he grew older, Custer's family instilled in him Methodism and the virtues of the Democratic party.

While living with his half-sister and her husband in Monroe, Michigan, Custer attended Stebbins Academy — but favored reading whimsical romance novels over studying. Upon returning to Ohio, Custer enrolled at McNeely Normal School at age 16. It took a year for him to acquire a teaching certificate, at which point Custer found himself teaching grammar school students. The occupation bored him silly, although he did stick around long enough to teach, briefly, at two different country schools. But the teen wanted more out of life and decided instead to apply to the United States Military at West Point. He was almost immediately accepted, says his biography on Little Bighorn Battlefield, and entered the Academy at only 17 years old.

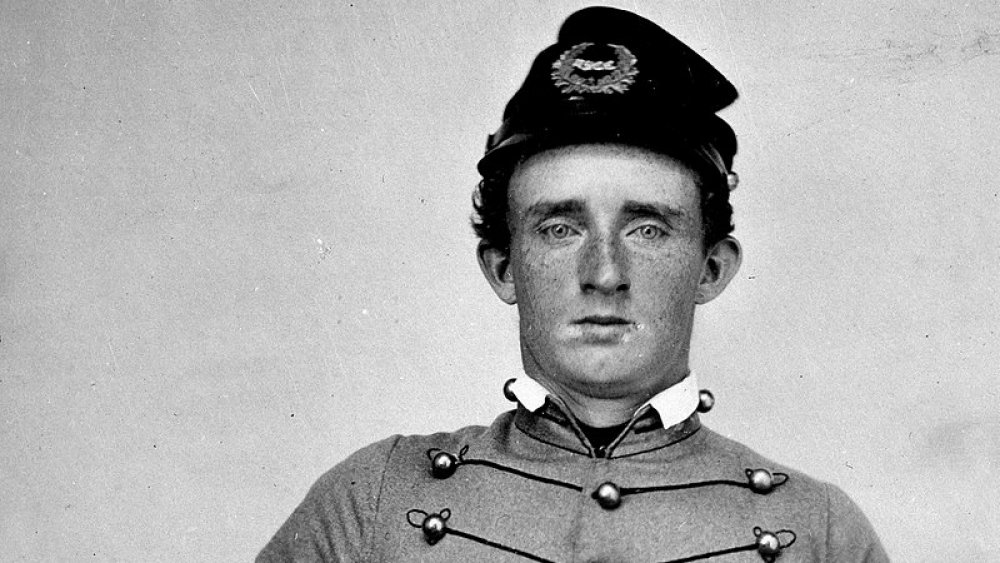

Custer was last in his class at West Point

Custer owed his acceptance to West Point to the father of Mary Holland, whose family he boarded with while teaching. According to HistoryNet, his love poems to Mary were almost erotic, and he was going to be booted from the Holland home. Upon deciding to attend West Point, Custer found that he needed a congressional appointment — something the local Republican congressman was unwilling to give. Mary's father, however, happened to be a Democrat and willingly gave his blessing as a means to get Custer away from his daughter. Little Bighorn Battlefield confirms that the boy began his studies in the fall of 1857.

But Custer was less interested in school than he was in causing trouble. His room was a pigsty, he chucked snowballs at his classmates, and when he was discovered wearing a wig to disguise his long hair, they shaved his head. On top of it all, he was always getting drunk at a nearby tavern, where he likely contracted gonorrhea. We Are the Mighty reports that the night before graduation in 1861, while on duty, Custer found two cadets arguing and suggested that they fight out their differences. As punishment, he was forbidden from attending his own graduation ceremony. Custer graduated last in his class of 34 cadets, but he was able to enroll in the Union Army as the Civil War broke out.

Custer became a brigadier general at age 23

Custer was dispatched to the 2nd Cavalry, according to Essential Civil War Curriculum, three days after leaving West Point. Battlefields describes his behavior as "aggressive, gallant, reckless, and foolhardy." Yet he was cited for "bravery under fire" when he boldly rode forth and transformed retreating soldiers into an orderly formation. He was soon assigned as an aide-de-camp for Brigadier General Phillip Kearney. Another time, as Major General John G. Barnard pondered whether it was safe to cross the Chickahominy River, Custer rode his horse right out into the middle of the water to see if it was. Higher-ups duly took notice and promoted him to Captain.

Over the next two years, Captain Custer continued climbing the ranks, serving under General George. B. McClellan, commander of the Union Army of the Potomac, per Britannica. Especially under General McClellan, Custer was able to meet and mingle with numerous other commanders. They took note of his outright, if sometimes brash, bravery. In 1863, Custer was made Brigadier General, a job that consisted of overseeing the Michigan Cavalry Brigade of the U.S. Volunteers. The brigade was made up for four regiments of men, which Battlefields equates to a few thousand soldiers. Custer, who was only 23 years old, was dubbed the "Boy General," but he'd soon make a name for himself across America during the Battle of Gettysburg.

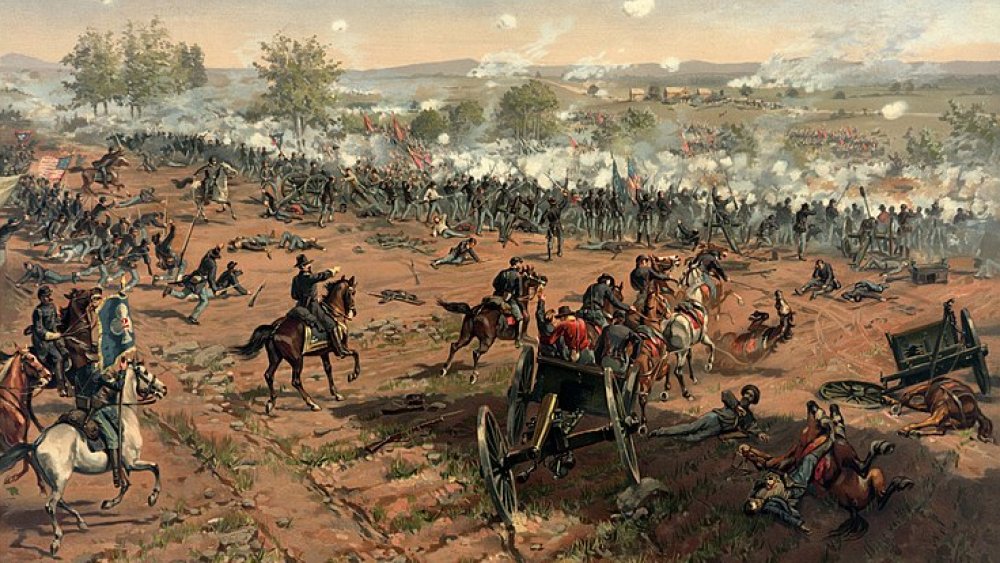

Custer at the Battle of Gettysburg

History verifies that the Battle of Gettysburg was one of the most important battles during the Civil War. Between July 1 and July 3 in 1863, Union and Confederate soldiers clashed, with casualties on both sides. The Union emerged victorious and stopped General Robert E. Lee from invading Northern territory. For Custer's part in the battle, the Boy General led several charges. In one instance, according to We Are the Mighty, his horse was literally shot out from under him. Undaunted, Custer found another horse and, during his final charge, shouted "Come on, you Wolverines!" as he raised his saber. The Confederates scattered.

Although 50 percent of the soldiers under Custer were killed, he was still respected and admired for his bravery. In far-north Vermont, the Burlington Free Press noted that Custer's men "captured more than man for man from an enemy whose force consisted of four times their numbers." The newspaper concluded proudly, "This is cavalry fighting, the superior of which the world never saw." Custer, meanwhile, furthered his bloody engagements at the Battle of Yellow Tavern and the Third Battle of Winchester in 1864, according to Britannica. Even as he fought his way through the Civil War, however, Custer had marriage on his mind. His chosen mate was Elizabeth Bacon, a gorgeous little lass whom Custer felt also was well worth fighting for.

The romance of George and Libbie Custer

In November 1862, according to History, Custer met Elizabeth Clift Bacon at a party. One look at the man with golden hair cascading down his back, and Libbie was smitten. The two began courting as Custer returned to fight in the Civil War. The couple's "relationship intensified" when Custer returned to Monroe during the winter of 1863. According to We Are the Mighty, however, Libbie's father initially disapproved of the courtship, because Custer came from a working-class family and drank too much. Nevertheless, the couple remained inseparable. They were engaged by Christmas and married in February 1864.

Libbie was a model Army wife, often staying near or with Custer. Custer snuck out at night to see her, and per Frontier Partisans, their love letters are legendary. When Libbie wrote of wanting a kiss, Custer responded, "Oh, I do want one so badly. I know where I would kiss somebody if I was with her tonight." Libbie put up with Autie's pranks and calling her "Old Lady," according to author Dee Brown. She also loved engaging in "wild games of romps" with him. Her shrieks as the two galavanted around their tent led others to believe "that the commanding officer was beating his wife." The rumor was untrue, and Libbie stayed faithful to her man for the rest of his life.

A court martial for Custer

Back at war, Britannica credits Custer with chasing down the Army of Northern Virginia and Confederate leader General Robert E. Lee. The South finally surrendered in 1865. As a reward, according to History, Custer was temporarily awarded the rank of Major General. With the war over, he decided to stay on, accepting a position as Lieutenant Colonel. In 1867, according to History Source, he was assigned to go west to handle the "Indian problem." Today, it is widely recognized that America's attacks on indigenous people were wrong on just about every level. In Custer's day, however, Anglos viewed the natives as grossly primitive and a force to be dealt with.

Custer did not fare well out West. In September, he was court-martialed for leaving part of his regiment in Kansas at Fort Wallace, without permission, to return to Fort Harker for supplies — and to see his beloved Libbie. Ten other charges included forcing his exhausted men to march on "private business," neglecting to pursue Native Americans or bury those already killed, and commanding his officers to shoot three deserters without trial. The men were seriously wounded, and one of them died after Custer denied him medical treatment. In the end, according to Encyclopedia.com, Custer was found guilty of five of the charges. He was suspended for a year, during which he did not receive pay.

Custer the unfaithful

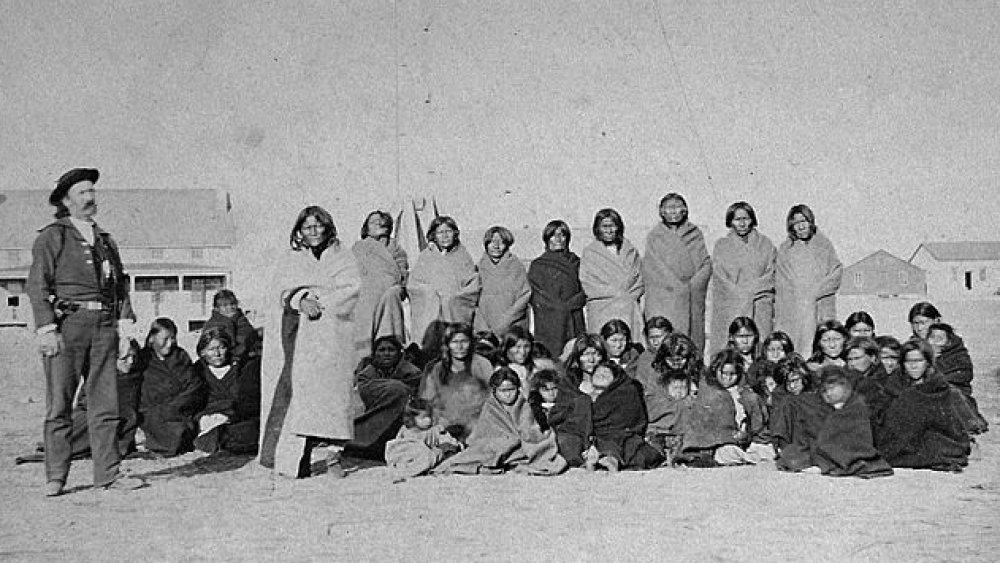

Libbie Custer may have been faithful to her husband, but the same cannot be said of ol' George. When Custer and his men attacked a Cheyenne village in the Washita Valley of Oklahoma on November 27, 1868, according to America's Library, a number of Native Americans were killed or captured. Of the captives (pictured) Custer took, he paid particular attention to a young woman named Monahsetah (aka Meotzi). HistoryNet recounts Custer's description of the maiden: "an exceedingly comely squaw, possessing a bright, cheery face, a countenance beaming with intelligence, and a disposition more inclined to be merry than one usually finds among the Indians." Clearly, Custer was quite taken with the girl.

Later, Libbie met Monahsetah at Fort Hays. Custer said she was his "interpreter," although she spoke no English. Libbie even admired the girl's baby, "a cunning little bundle of brown velvet with bright beadlike eyes," wrote Dee Brown. Many claim that Libbie "pretty plainly knew about the extramarital affair," but it is unclear whether she recognized the baby's yellow hair — just like Custer's. Monahsetah named him Yellow Swallow, and nobody is sure what became of him. As for Monahsetah, Indian Country Today maintains that she remained faithful that "Long Hair" would come back to her, mourning him by "cutting her hair and gnashing her arms" when he died.

Custer the narcissist

Indeed, George Custer was all about himself. Aside from his marital indiscretions, according to History, he loved wearing a black velvet uniform trimmed in gold lace, with a bright red scarf around his neck and a "large, broad-brimmed sombrero." As for his golden tresses, Custer favored perfuming his hair with cinnamon oil. According to Biography, Custer even saved locks of his own beloved hair so that he could have a wig made in the event he lost it. Incidentally, a surviving lock of Custer's hair, owned by American West collector Glen Swanson, sold at Heritage Auctions in 2018 for a whopping $12,600.

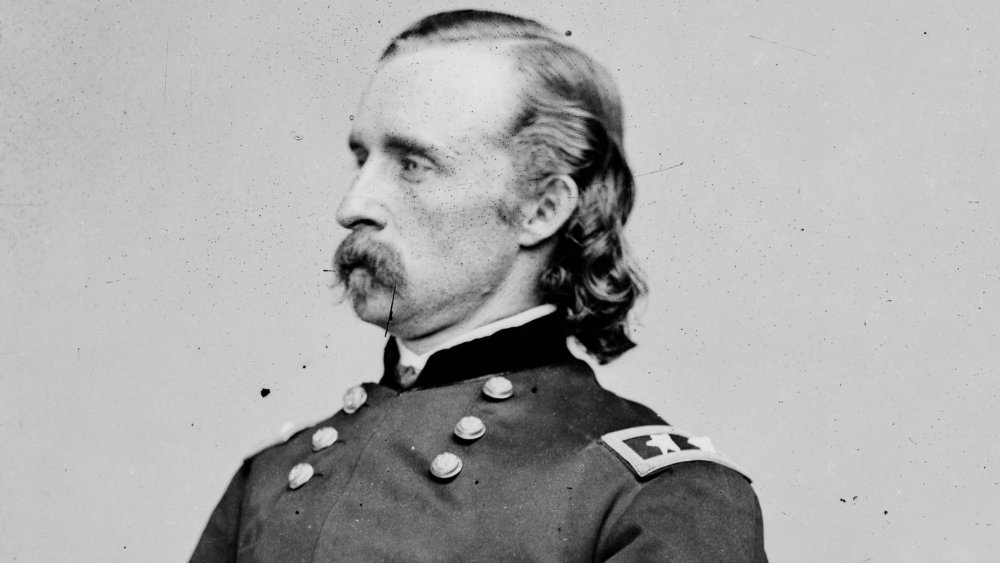

Custer's biggest monument to himself was his 1874 book, My Life on the Plains. The book, according to Amazon.com, was comprised of a collection of articles Custer had written. It is touted as "an intensely personal account," even as it included such hypocrisies as, "If I were an Indian, I often think I would greatly prefer to cast my lot among those of my people who adhered to the free open plains, rather than submit to the confined limits of a reservation..." Colonel Frederick Benteen (pictured above), who was with Custer at Washita battlefield and "took an immediate dislike" to Custer, saw through his flagrant fling at self-promotion. Benteen called the book "My Lie on the Plains," according to authors Edward Caudill and Paul Ashdown.

Custer nearly missed Little Bighorn

Custer nearly didn't go to Little Bighorn after testifying in 1875 that President Ulysses S. Grant's brother, Orville, was one of several officials accused of selling "exclusive trading rights" at various forts and trading posts. The president was incensed, according to Little Bighorn Battlefield, as Custer not only testified against Secretary of War William Belknap (pictured), but also Orville Grant. Although Grant held Custer's testimony against him, he finally relented in the spring of 1876 so that the fearless commander could take his 7th Cavalry to clear out the Lakota and Sioux tribes and force them onto the Great Sioux Reservation in South Dakota.

Notably, Custer's men also disliked him intensely. He was, after all, an egotistical, prankster/bully who had abandoned his men in Kansas, put himself before all others, and frequently failed to listen to his superiors. We Are the Mighty also commented on his "hypocritical leadership style that tended to trash morale." Custer biographer T.J. Styles expressed a slightly different opinion of Custer's relationship with his men. "In wartime his men loved him," Styles said in an interview with Cowboys & Indians. "But he failed as a manager under routine circumstances. He compensated with a high-handed manner, alienating subordinates and superiors." Under this questionable leadership, Custer's men followed him to the Little Bighorn River in late June 1876.

Custer's last stand

Custer's failure and subsequent death at Little Bighorn has been called the worst defeat in American military history. The story is achingly familiar: Eyewitness to History explains how, after dividing his men into teams, Custer and 209 of his men attempted to cut off one end of a Sioux village along the Rosebud River. Custer believed there were only 40 warriors there, but the actual number was three times his own force. Both Cheyenne and Sioux warriors "slammed into the advancing soldiers," killing everyone. Ironically, one of the warriors, Chief Magpie, had managed to escape Custer's massacre at Washita, according to America's Library.

Per History, Custer died of two gunshot wounds, but reports vary as to whether his body was stripped, scalped, and dismembered like the others, whether Custer lay untouched because he was not wearing his uniform (or, perhaps because he had an affair with a Cheyenne maiden), or whether his eardrums were pierced for his refusal to listen. But America was so caught up in Custer's defeat that history has nearly forgotten that four other family members also died at Little Bighorn. Shapell claims that Custer's brother, Tom, rode beside him as he was wounded and may have shot Custer in the head to prevent the natives from torturing him. Tom was found near Custer's body, riddled with arrows. Nearby were Custer's nephew Autie Reed, his brother-in-law James Calhoun, and his youngest brother, Boston.

Libbie's tributes to Custer

On the morning of July 6, Libbie Custer, according to HistoryNet, was visited by Captain William McCaskey, who told her that Custer had died. McCaskey would later recall his hour-long visit as being "the most difficult of his life." Custer's death marked the end of Libbie's time as an Army wife, meaning that she had to vacate her quarters at once. She did receive a $5,000 life insurance payout and a $30 monthly widow's pension. When Colonel Nelson Miles visited her, she was "depressed and in such despair." For a time, Libbie stopped seeing her friends at all, explaining to others, "A wounded thing must hide."

But Libbie Custer was resilient, defending her husband to the public "as a brave, gallant, and noble figure struck down before his time," says Little Bighorn Battlefield. Later, she would write three memoirs about her time with Custer: Boots and Saddles, Tenting on the Plains, and Following the Guidon. Libbie's books have been criticized for making Custer look better than he was, but she wasn't finished. Instead, she became "a professional widow," traveling and giving talks about her beloved Autie. It was quite a career. When she died in 1933, Libbie Custer's estate was valued at $100,000, the equivalent of millions today. She is interred beside her husband at West Point.

Buffalo Bill and Custer's last stand

Libbie Custer's efforts aside, it was the great showman Buffalo Bill Cody who memorialized the Battle of Little Bighorn and its infamous martyred hero. Shortly after Custer's death, according to History, Cody (who once scouted for Custer) killed and scalped a Cheyenne called Yellow Hair. He called the trophy "the first scalp for Custer." But it wasn't Cody who first incorporated "Custer's Last Fight" into his Wild West show but Adam Forepaugh, who first re-enacted the famous battle in his own show beginning in 1887, according to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West. The following year, Cody countered with an even grander show featuring the scalp of Yellow Hair.

Surprisingly, Libbie once attended Cody's show. She later wrote to him, commenting on "her emotional reaction to its 'terrible' realism." Spurred by her compliments and his own ego, Cody fine-tuned his show to include Native Americans who were actually at the Battle of Little Bighorn. But Cody wasn't alone in exploiting the battle and its fallen leader. Pawnee Bill also reenacted Custer's death (performance pictured above), and the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History reveals that the Anheuser-Busch Brewing Company came up with framed prints of the battle, which soon graced the walls of saloons across America. The original painting was destroyed by fire in 1946, but original chromolithographs and replicas are still for sale online today.