The Messed Up Truth Of Catherine The Great

Catherine II, or Catherine the Great as she's best known today, has earned her place in history as one of Russia's best-remembered rulers and one of the world's most influential queens. She was never even supposed to rule — that was supposed to be her husband, Emperor Peter III. However, through sheer intelligence and cunning, Catherine not only managed to escape a miserable political marriage, but she successfully wrested power away from her husband and claimed the Russian throne for herself. She held power in Russia for the next 35 years — up until her death — making her the longest-reigning female ruler in Russian history.

Catherine is credited for shifting Russia from a provincial, rustic country to a paragon of European splendor and power. There have been many stories about the legendary monarch, and new interest in the infamous Russian Empress has been sparked thanks to Hulu's new series, The Great — loosely based on the monarch's early years. But the real story of Catherine the Great shows that the truth can be stranger than fiction.

Catherine the Great wasn't actually Russian

She is best remembered as the Empress of Russia, but Catherine the Great was actually of German descent. According to Smithsonian Magazine, she was born in 1729 in central Germany, which was once known as Prussia. As noted by History, her birth name wasn't even Catherine — she was christened Princess Sophie von Anhalt-Zerbst. The young princess' parents were impoverished Prussian royals, but what they lacked in wealth, they made up for in noble connections – her mother was especially ambitious to secure an advantageous marriage for her eldest daughter.

It was thanks to her parents' notable ties that Sophie's mother was able to arrange an in-person introduction for her daughter with Czarina Elizabeth of Russia, who was looking for a bride for her nephew and heir, Peter — a grandson of Peter the Great. Well-trained by her mother, Sophie charmed the Czarina with her good looks and lively, engaging personality. The match was made, and the 16-year-old Sophie was to be wed to the 17-year-old Peter. Upon her betrothal to Peter, Sophie converted to Russian Orthodoxy and was baptized with the new name of Catherine — or, in Russian, Ekaterina.

Catherine was greater than her husband

Although Catherine's family were likely thrilled that their daughter had snagged such an impressive marriage — to the future emperor of Russia, no less — Catherine was less than thrilled with her new husband. Her marriage to Peter was a disaster from the onset. According to Biography, their relationship got off to a bad start after Peter abandoned his new bride on their wedding night to go off and party with his friends — and things only got worse from there. Catherine's accounts of her husband in her letters and memoirs tell of a marriage to a cruel, drunken boor whom she couldn't bear to be near.

Peter was reported to be a poor student and immature, while Catherine was highly intelligent and had a great love for European culture. According to Smithsonian Magazine, she embraced her new homeland, and her husband still clung to his father's Prussian roots. (His mother was Russian, and Peter was adopted by his aunt.) Peter tried desperately to create an image for himself as a strong military commander, but according to Town and Country, more of his military experience came from playing with his toy soldiers than from successfully commanding real ones. Meanwhile, Catherine busied herself with her intellectual interests, such as reading about the Enlightenment authors and perfecting her knowledge of the Russian language. With their drastically different interests and personalities, it wasn't long before both Peter and Catherine were taking other lovers.

Catherine the Great's son might not have been legitimate

Although their marriage was unhappy, Catherine and Peter managed to secure an heir for Russia, or at least Catherine did. There is some evidence that Catherine's son Paul might not have been Peter's legitimate son. According to History, some historians suspect that Peter might have been infertile, and others have questioned if Peter was even able to consummate the marriage at all. Catherine didn't even become pregnant until eight years after they were married — highly unusual for a royal marriage. Given that Catherine and Peter's marriage was so notoriously dysfunctional, plus both were openly having affairs, the questioning of Paul's legitimacy would not have been unheard-of.

There has been heavy speculation that Paul might have been fathered by Catherine's lover at that time, military officer Sergei Saltykov. Even Catherine openly acknowledged that Czarina Elizabeth had been complicit in allowing her relationship with Saltykov, fueling the rumors of Paul's paternity even further. Catherine had three other children after Paul, and while Paul's legitimacy might still be debatable, historians are in general agreement that Catherine's other children were almost certainly not fathered by Peter. Her daughter, Anna (possibly fathered by Stanislaw Poniatowski), died at age two while Peter was still alive. Alexei and Elizabeth — likely the offspring of Grigory Orlo and Grigory Potemkin, respectively — were sent away at birth and raised in other households.

Catherine the Great was a usurper

When Czarina Elizabeth died in 1762, Peter and Catherine were crowned Emperor and Empress of Russia. Peter III had a notably short reign as emperor — only six months. Having spent her time as a grand duchess studying and improving her mind, Catherine came to the conclusion that the drunk, bumbling, and poorly educated Peter would be an unfit ruler — unlike herself. She decided that Peter had to go.

With her lover Grigory Orlov, Catherine planned a coup to overthrow Peter and take the throne for herself. A talented equestrienne (unlike her husband), Catherine led a group of 14,000 soldiers on horseback to storm the Winter Palace. After being successfully dethroned in a bloodless coup, Peter was forced to sign his abdication and was immediately thrown in jail. He died in jail soon after he was deposed. While it was originally thought that Catherine was the cause of Peter's death, historians find this debatable. According to Harper's Bazaar, theories include that Peter could have been assassinated — possibly by Grigory Orlov's brother, Alexei — and there is some evidence that Peter may have committed suicide. Regardless of the cause of Peter's death, Europe blamed Catherine.

Catherine the Great was a great patron of the arts

As a result of her intense years of study when she was still a grand duchess, Catherine considered herself an enlightened despot and one of Europe's most progressive rulers. When Catherine first ascended the throne, Russia was regarded by other European countries as backwater and provincial. According to Biography, Catherine was determined to remake Russia's world image. A great champion of the arts, Catherine used art and architecture both a tool to show off Russia as a model of modern Western European culture and, of course, for her own personal enjoyment. She sponsored many artistic and cultural projects for the betterment of the country and had a theater built in St. Petersburg. Catherine herself even contributed a few librettos to be performed there. Catherine was also a great fan of the playwright Voltaire, with whom she had a lifelong correspondence.

One of Catherine's most notable legacies to Russian culture and history was her vast collection of art, which she housed in the St. Petersburg Winter Palace, now known as the Hermitage Art Museum. Additionally, as a self-taught woman herself, Catherine sought to make education more available, especially to women. She created a St. Petersburg boarding school for the daughters of noblemen and later called for the establishment of free schools throughout Russia.

Catherine the Great was extremely militaristic

Russia enjoyed great prosperity and strides in the arts during the reign of Catherine the Great, but none of this would have been possible without Catherine's military ventures. According to Smithsonian Magazine, as she waged war on the Ottoman Empire for control of the Black Sea, Catherine turned her attention to the Crimean Peninsula — a key area. Home to a predominantly Muslim population from intermarriage between the Turks and the Mongolian armies from the time of Genghis Khan, Crimea had a turbulent history with the Russian and Polish-Lithuanian Empires due to raids on their territory. Russia ultimately annexed Crimea in 1783, to the annoyance of the rest of Europe. Claiming Crimea for Russia gave Catherine the control she desired over key ports of the Black Sea.

Between the Russo-Turkish Wars and three separate partitions of Poland, Catherine continued to acquire more territory for the empire. The once-independent Poland was divided among Prussia, Austria, and Russia — and Russia's slice of the pie included large portions of modern-day Ukraine, Lithuania, and Latvia. By the end of her reign, Catherine had added over 200,000 square miles of territory to Russia, per Britannica.

You wouldn't want to be a serf under Catherine the Great

While Catherine is credited for bringing great reform and modernization to Russia, this was not the case when it came to the country's use of serfs. The Russian economy depended heavily on the use of serfs, who comprised most of the population, and the demands of the state led to even more demands on the nobility and their serfs. While it would appear that Catherine may not have personally favored the institution of serfdom, she learned that she would have to rely heavily on the nobility to help keep order in Russia — and, in turn, keep herself in power. This led to her appeasing the nobles by granting them far more control over their lands and serfs to keep them content.

However, serfs were essentially a type of slave — and their working conditions were horrible. According to Live Science, the serfs who worked in factories, mines, and foundries rarely lived to middle age. In 1767, Catherine passed a declaration that condemned serfs for protesting against their conditions — something that would come back to haunt her in the form of a great rebellion against her.

Catherine the Great combatted several uprisings

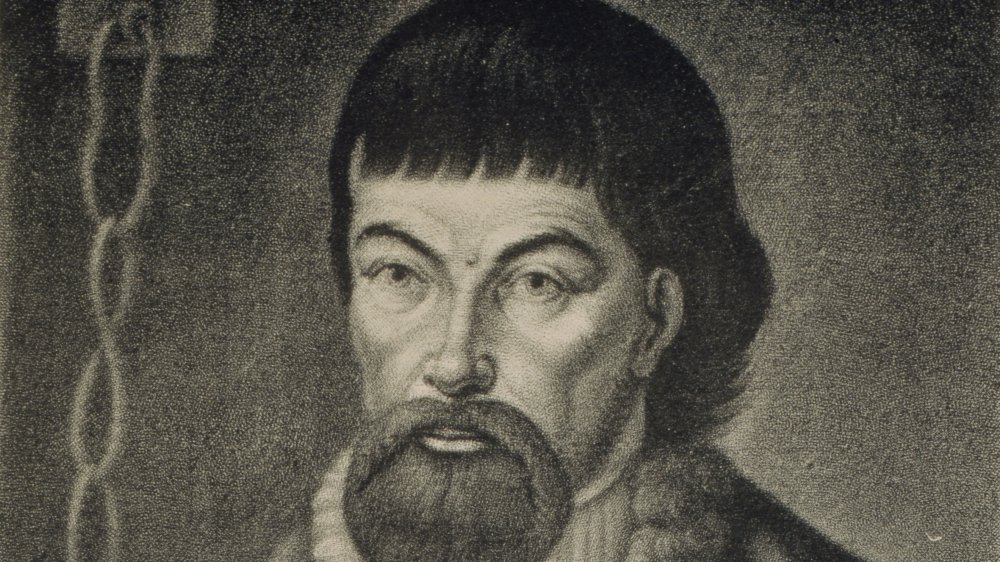

Although Catherine managed to stay in power until the end of her life, her throne was often under threat — unsurprisingly, given the controversial way she came to rule. While she ended up having to fend off more than a dozen uprisings during her reign, the most dangerous insurrection proved to be Pugachev's Rebellion.

Catherine's new laws regarding Russia's serfdom proved upsetting for the serfs themselves, as they were not only being forced to work in poor conditions, but they were even forbidden from protesting. In 1773, Emelyan Pugachev, a former army officer, led a troop of armed peasants to rebel against Catherine's reign. According to History, Pugachev claimed to be Catherine's deposed husband, Peter III, and the true ruler of Russia. Catherine's reign was always tenuous at best, and this claim was enough to call her rule into question. Pugachev was able to garner thousands of supporters, enough to conquer the city of Kazan and a significant amount of territory. Once Catherine realized the danger that Pugachev posed to her rule, she responded to the uprising with the enormous force of the Russian Army. Once the peasant army saw what they were up against, most deserted Pugachev, who was soon captured and publicly executed.

Catherine the Great loved love

Catherine knew that the best way to hold on to her power was to avoid marriage. Besides, she had been married once before, and everyone knew how well that relationship ended — she probably had little desire to repeat the experience. But avoidance of marriage did not stop her from taking lovers, and she had many throughout her life. According to History, Catherine started having affairs while she was still married — first with officer Sergei Saltykov (who may have been the father of her son, Paul) and later with Grigory Orlov, who helped her overthrow Peter. Other notable names in Catherine's life included Russian nobleman Grigory Potemkin and Polish noble Stanislaw Poniatowski. Being the Empress's lover was a most coveted position, given how well Catherine treated her paramours. Even after the relationships ended, Catherine still generously lavished her former loves with land, titles, serfs, palaces, or political backing.

Although tales of Catherine's supposed promiscuity and nymphomania pervaded Europe, the reality was that despite having many lovers, Catherine was actually quite the "serial monogamist," as detailed by Biography. Catherine was never involved with more than one person at a time, and several of those relationships lasted for many years. It wasn't until her later years that she started taking on younger, more short-term lovers, and she absolutely never engaged in bestiality or tried to have sex with a horse — a popular rumor spread by her enemies.

Catherine the Great deliberately infected herself with smallpox

Catherine was very excited about advancements in medicine and was eager to introduce new developments to Russia. In 1767, an epidemic of smallpox wiped out over 20,000 people in Siberia, and the rest of Europe was desperately searching for ways to cure and prevent the deadly disease. At the time, British doctor Thomas Dimsdale was experimenting with a method of inoculation wherein the patient is deliberately infected with a mild form of the disease so the body can protect itself from any future infections.

Anxious to protect the people from a smallpox outbreak, Catherine invited Dr. Dimsdale to Russia. According to the Daily Herald, Dimsdale initially wanted to test out the vaccine on some of the common people to see how the inoculation would take in a Russian versus a British person. However, there were no takers among the people. Instead, Catherine volunteered herself and her son, Paul, to be the first vaccine patients in order to establish the doctor's credibility. She was inoculated on October 12, 1768, and developed a mild case of smallpox but fully recovered by the end of the month. As noted by Time, Catherine and Paul's positive results led to a mass inoculation program in Russia, and by 1780, 20,000 people had been treated. As a reward for his efforts, Catherine named Dr. Dimsdale a Baron of the Russian Empire.

Catherine the Great did not get along with her son

Paul was Catherine's only living and — at least for appearance's sake — legitimate child and her only heir, but the two did not particularly like each other. According to Harper's Bazaar, Czarina Elizabeth took Paul away to raise him when he was born, and once Catherine took the throne when he was eight years old, she had little time or inclination to give her son much attention. Also, Catherine didn't have high regard for her son. Despite the fact that he was her heir, she didn't consider him very intelligent and wasn't convinced that he would be a competent ruler.

One thing was for sure: There was no way she would abdicate in his favor as long as she was alive. As noted in History Today, Catherine married Paul off to a German princess and sent them away to live in Gatchina — far away from St. Petersburg and away from serious affairs of state. Paul — much like Peter III — entertained himself with meaningless military exercises and parades. Once Paul had children of his own, Catherine stepped in and took over their upbringing. Catherine had such doubts about her son's abilities that it was rumored that she was planning to bypass him in the line of succession in favor of her grandson, Alexander. However, she died before she could set such a plan in motion.

Catherine the Great's death was less eventful than rumored

There were many outlandish rumors about how Catherine the Great died. Some said she died on the toilet — others said she died while attempting to make love to a horse. All of these rumors were false. The truth of Catherine's death is far more ordinary than the rumors would have people believe — she simply died in bed of a stroke in 1796, at the age of 67. It was after her death that the more salacious rumors emerged, spread by her enemies (both foreign and domestic) to discredit Catherine's accomplishments.

Catherine's son Paul did succeed his mother after her death. According to History Today, Paul proved as inept a ruler as Catherine had feared. He immediately set about reversing her trademark policies, which drastically weakened the power of the aristocracy. Fearing the influence of the French Revolution, Paul forbade his subjects from traveling abroad and banned the import of foreign reading material. To seemingly further spite his deceased mother, as noted by History, Paul even signed a decree that forbade a woman from ruling Russia again. This law would carry over into the next century. However, Paul's reign did not last long — he was assassinated after only five years. His eldest son, Alexander, took the throne as his grandmother had apparently wanted all along.