The Full Timeline Of How America's Police Became Militarized

There's little doubt that we as a country are going through some stuff. Policing in the United States has been a topic of discussion for decades now, with the need for some sort of police reform front and center. It's easy to see why, when demonstrations against police misconduct and brutality inspire real-time examples of both problems, but those images of police departments that look more like the forces of a sci-fi dystopia have raised the important question: How did we get here? After all, studies have shown that militarizing the police is ineffective as a strategy against crime and very effective in targeting minority neighborhoods and demonizing citizens exercising their rights to free speech and assembly.

Despite these obvious drawbacks, police departments continue to receive billions of dollars in military equipment every year and are increasingly trained in aggressive tactics that favor the concept of "enforcement" over peacekeeping. Although the process has accelerated in just the last few decades, the full timeline of how America's police became militarized goes back two centuries and deals with a lot of history that America would prefer not to remember in too much detail.

Pre-Civil War

The idea of a professional police department is a relatively modern one. As Time points out, when the United States was born, policing was a largely informal and privatized affair. Towns would hire part-time law enforcement when needed and relied on a simple night-watch system to ensure that property and lives were protected.

It wasn't until the country began to prosper and cities began to grow that these inefficient systems began to be supplanted by full-time, professional police — but the country, already divided into northern and southern states, followed two different paths. In the North, this was largely driven by merchants who wanted to protect their merchandise but didn't want to keep paying for private security. In grand capitalist fashion, they lobbied to have policing become a public expense. The first full-time police department was created in 1838 in Boston. According to Professor of Justice Studies Gary Potter, New York City followed in 1845, and by the 1880s, just about every major city in the country had a police department.

In the South, however, policing began with the creation of slave patrols, the first of which was founded way back in 1704. Slave patrols were charged with keeping the slave population in line through terror and brutality, chasing down escaped slaves, and putting down any slave revolts. These patrols formed the roots of the police departments that were created in the South after the Civil War.

Post-Civil War

Back in the 1860s, this country fought a war over slavery that, in typical American fashion, we refer to as The Civil War. As MinnPost explains, when the Confederacy surrendered, the Northern troops remained for years as a peacekeeping force. The soldiers acted as police and law-enforcers and were instrumental in allowing former slaves to enter society as free, equal citizens. As History reports, immediately after the Civil War, a period known as "Radical Reconstruction" led to the first black representatives being elected to Congress — a total of 16, with hundreds elected to state legislatures.

The Southern states raged against these measures, but with the federal troops in place, there wasn't much they could do. In the presidential election of 1876, they saw their chance. The race between Republican Rutherford Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden was so close that the South offered a deal: They'd concede the election to Hayes if the troops were recalled. This was done, and a few years later, the Posse Comitatus Act 1878 was passed, forbidding the use of the armed forces for enforcing domestic laws.

This left a law-enforcement vacuum, which was easily filled by the old slave patrols that had once kept the black population in line. As USA Today points out, these patrols did everything a police department did — with the twist that they were blatantly race-oriented. Very shortly, all the progress the former slaves had made was virtually erased — and those slave patrols evolved into modern-day police departments.

The Gilded Age

The idea that the police exist to protect and serve the population in general, ideally without prejudice or politics, is a pretty new one. In fact, in the late 19th century — a time of immense economic inequality in this country, usually referred to as the Gilded Age — police were seen more as population control.

As Sam Mitrani, PhD, Associate Professor of History at the College of DuPage, writes for the Labor and Working-Class History Association, the vast gulf between the obscenely wealthy and the poor working-class people led to a lot of civil unrest. That unrest led to demonstrations that occasionally devolved into riots, but what really scared the One Percenters was the rise of organized labor and the strikes it inspired. The police were used to ruthlessly and brutally suppress these strikes.

As a result, police began to define themselves as that "thin blue line" that stood between civilization and chaos — by which they meant rich people and poor people. In fact, as Dr. Mitrani notes, many police departments were specifically organized to be outside the control of the local populations, and their traditions and policies were purposefully designed to set police apart from the communities they supposedly served.

The early 20th century

Once police departments became a normal part of everyday life for Americans, it wasn't long before a drive to make them more professional and more disciplined came into force. As LA Weekly notes, many of the decisions that ultimately militarized the police were initially regarded as reforms. In the early 20th century, many veterans of America's more recent wars returned home and found work in police forces, bringing with them their training and admiration for military organization.

One of the most influential was a man named August Vollmer, who became Chief of Police for Berkeley, California, in 1909. Vollmer was a former Marine and a veteran of the Spanish-American War, and as Berkeleyside reports, he vigorously applied his military experience to the police force he now commanded. In fact, as The Independent notes, Vollmer was the man who invented the office of "Chief of Police." He also instituted the command structure that's familiar to us today and introduced modern concepts of policing like strict reporting and record-keeping, forensic evidence gathering and analysis, and the use of radio communications.

Vollmer is known as the father of modern policing and was instrumental not only in making police work more modern and reliable but also in the literal militarization of the police. Without Vollmer's war-inspired changes, police forces would not have so easily mutated into the paramilitary organizations we so often see today.

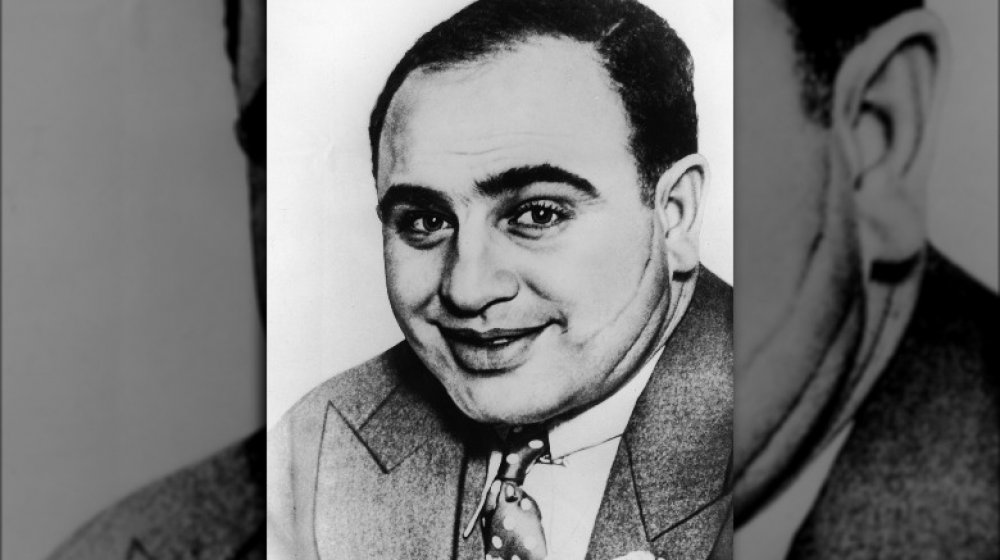

Prohibition

It seems hard to believe today, but there was a time when alcohol was largely illegal in this country. Prohibition was voted into law in 1919 and lasted until 1933. That's just 14 years — but it was long enough to have a lasting impact on the police.

Prohibition was controversial. Plenty of otherwise law-abiding citizens were determined to hang onto their drinking habits, and this gave rise to an incredibly lucrative black market for alcohol, exacerbated by the fact that booze remained perfectly legal in neighboring countries like Canada. As the Foundation for Economic Education notes, this led to the rise of organized crime in this country — there was simply so much easy money to be made.

The crime syndicates that arose from this situation were in constant, violent battle with each other, and the iconic image of the machine-gun-toting gangster took hold. The gangs were well-armed, and the police, charged with stopping them, increasingly adopted similar practices. Police began carrying automatic weapons like the Thompson Submachine Gun and using armored vehicles for the first time. This violent period of history also established the popular belief in the necessity of a heavily armed police force capable of dealing with the most dangerous criminals.

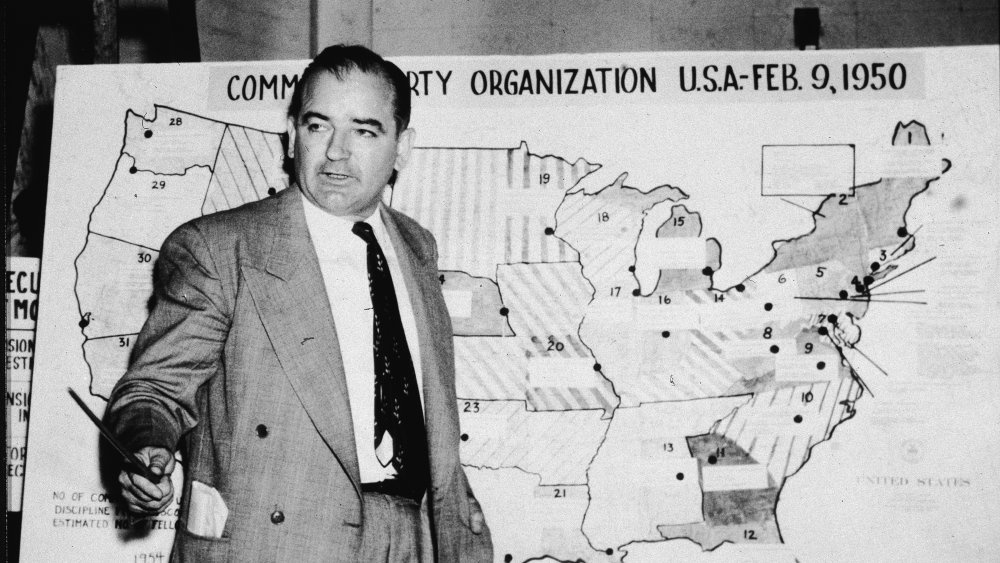

The Cold War

After World War II remade the world map and elevated the United States and the USSR to superpower status, America entered into a period of "Cold War" marked by paranoia and fear. The idea that communist "infiltrators" were embedded in every aspect of our society led to the Red Scare, the McCarthy Hearings — and a radical shift in how police viewed the citizens they served.

As The Conversation reports, this new paranoia led the government to view any demonstration or protest movement with suspicion. It began to categorize the people involved with them as potential revolutionaries or traitors, and this attitude was passed down to the police departments charged with reacting to protests — the police were literally instructed to treat demonstrators as enemy combatants.

Worse, viewing American citizens as enemies and traitors who deserved violent suppression was given a scholarly and scientific gloss through the use of studies funded by the Department of Justice. And these studies usually targeted minority communities, heavily implying that, if left unchecked, agitators would inspire these communities to rise up and start a race war. These Cold War-era fantasies had a permanent influence on policing in this country, giving police departments around the country justification for the violent and racially motivated violence they unleashed on Americans using their right to free assembly and speech.

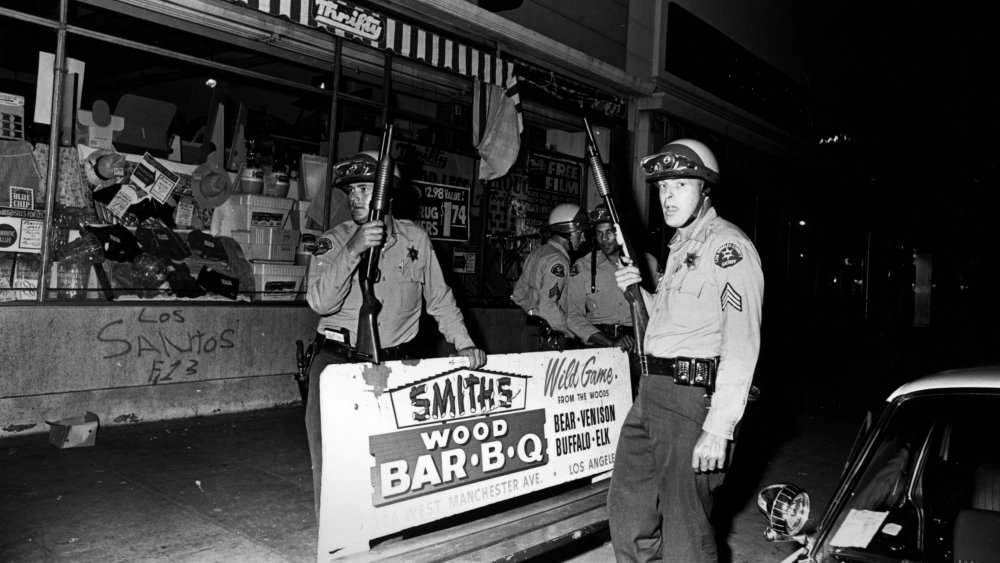

The Watts Riots

Far from an era of peace and love, the 1960s were a turbulent and violent time in America. During World War II, millions of black Americans moved to California to escape the racial segregation of the South and to seek employment — the black population of Los Angeles increased greatly between 1940 and 1965. So did racial tensions, and on August 11, 1965 a now-familiar scene played out: A black man was pulled over by police, events escalated into a violent confrontation, and for the next six days, the Watts neighborhood in Los Angeles was engulfed in a riot.

The damage was incredible, and the city learned all the wrong lessons from it. As LA Weekly reports, instead of seeking better understanding and relationships, it instead turned to former Marine Sergeant John Nelson and future Chief of Police Daryl Gates to form the first special weapons and tactics (SWAT) team. Since the Posse Comitatus Act 1878 forbid the federal government from sending in troops to enforce laws, and the National Guard was under the governor's authority, SWAT teams were seen as a way to respond to violent riot situations like the ones in Watts.

The New York Times notes that Gates' SWAT experiment was deemed an authoritarian success after clashes with the Black Panthers and other groups in the 1960s and 1970s, and before long, every major police department had a SWAT team explicitly charged with a military-style response to civilian disorder.

The 1967 Detroit Riots

On July 12, 1967, riots swept the city of Newark. Two weeks later, on July 23, 1967, police raided an illegal after-hours bar in Detroit in a sweltering, economically devastated black neighborhood, sparking another violent riot. These riots were racially motivated — black communities rising up against police departments staffed almost entirely by white men and perceived more like occupying armies than peacekeepers. They also gave credence to the idea that law and order was crumbling in America. Chaos seemed to reign everywhere, and the impression was that cities didn't have the resources to handle problems at this scale.

The result, as Timeline reports, was twofold. One, SWAT teams were formed to provide a military-style response to riots and other dangerous situations. And two, the Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. This created the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA), which gave federal grants to police departments for the purchase of military-grade equipment and the creation and training of SWAT teams and similar units.

So just as SWAT teams, literally modeled on anti-terrorist military units and tactics, were being formed, the federal government started handing out money so they could buy high-powered weapons and advanced crowd-control technology.

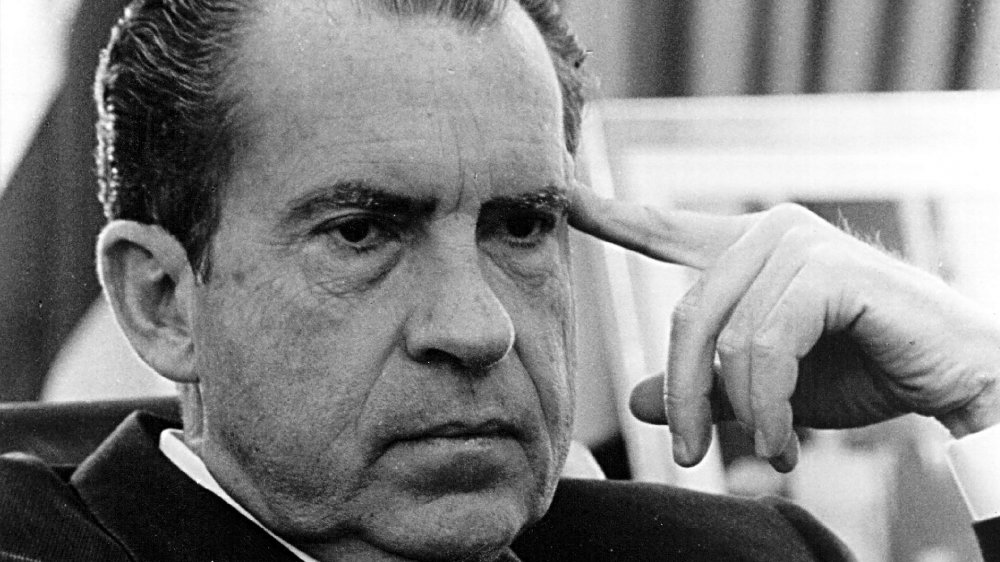

The war on drugs

If you've recently heard the term "law and order president," know that it's not new. Richard Nixon dubbed himself the "law and order" president back in the early 1970s, and he launched the first "war on drugs" in this country.

As Vox reports, drug use spiked in America during the 1960s for a wide variety of reasons, but it became closely associated with the countercultural movement that many conservative Americans saw as inherently untrustworthy and potentially traitorous. Nixon's aggressive attitude toward the scourge of drug use in the country was a response to those attitudes — but as with so many aspects of American history, there was a strong racial context to it. As USA Today notes, Nixon's war on drugs (and other attempts to be "tough," like New York's Rockefeller Drug Laws) disproportionately targeted blacks and other minorities — a fact that Nixon's domestic policy chief John Ehrlichman explicitly confirmed.

The use of the term "war" also served to justify the aggressive, heavily armed policing that was becoming the norm around the country. It completed a psychological shift from peacekeeping to law enforcement that had begun decades before and gave police departments every excuse they needed to militarize — because they were at war.

The crack epidemic

The war on drugs may have begun in the early 1970s, but it really took off in the 1980s with the advent of crack cocaine. President Ronald Reagan doubled down on the aggressive tactics born in the Nixon era. As Vox reports, anti-drug policies enacted under the Reagan administration have resulted in the spending of more than $1 trillion over the last four decades.

Reagan also ushered in a series of policies and new laws designed to help police departments fight this war. The most notable, according to writer and historian Christopher J. Coyne, was the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, which created the Department of Justice Assets Forfeiture Fund. While civil asset forfeiture is an old and well-established legal technique, the Comprehensive Crime Control Act actually gave police departments incentives to aggressively pursue civil forfeitures for their own profit.

The end result was twofold. On the one hand, it further encouraged police to regard citizens as the enemy, a group who could be relieved of their property with impunity. Two, it gave the police another source of funds for advanced, military-style weapons and equipment – USA Today reports that as of 2017, the federal governments forfeiture fund was more than $1.5 billion.

The Miami and North Hollywood Shootouts

Two incidents further pushed the narrative that police departments needed to be militarized: the 1986 Miami Shootout between the FBI and two bank robbers and the 1997 North Hollywood Shootout. In both cases, the police enjoyed tactical and numerical superiority against criminals but were at a severe firepower disadvantage. In both shootouts, the criminals used high-powered automatic weapons, which allowed them to pin down the police for hours.

As the LA Times notes, two men involved in the 1997 shootout, Larry Eugene Phillips Jr. and Emil Dechebal Matasareanu, wore body armor that made them almost impervious to the small-arms fire of the police and carried much more powerful weapons. It wasn't until LA's storied SWAT team arrived that the criminals were killed. The whole shootout was broadcast on television. It all added up to the obvious conclusion that the police were dangerously outmatched by a new breed of well-armed criminal, and as The Atlantic notes, this, in turn, led to the 1033 Program.

The 1033 Program is a Department of Defense program that moves surplus military equipment to police departments. It was initially restricted to anti-drug uses but was later expanded to include anti-terrorist units. After the North Hollywood Shootout, the program was aggressively expanded. If you're wondering how the police get all those expensive, military-grade toys, the answer is the 1033 Program.

9/11

The 9/11 terrorist attacks changed everything. Three days later, President Bush declared a War on Terror, and there was a rapid shift in the way terrorism was combated. As The Atlantic reports, prior to 9/11, anti-terrorism was largely seen as the domain of law enforcement. Once the War on Terror was launched, the military began to take on this role — and the police began to mimic military tactics and postures as a result.

As Forbes reports, the passage of the Patriot Act in October 2001 not only increased the already substantial access police departments had to military equipment (including, in some cases, actual tanks), but it also changed the rules by which the police had to operate. The introduction of new tactics like "sneak and peek" warrants that allowed the police to break into someone's property to conduct a search without the owner's knowledge or permission ramped up a sense of lawlessness.

More importantly, the rhetoric of the War on Terror can be seen as the final step in transforming police departments into military-style units that use the same equipment and operating rules as the military.