The Messed Up Truth About Gone With The Wind

While the recent decision by HBO to pull Gone with the Wind from HBO MAX until it can be put into "historical context" might seem like a modern development, the fact is both the iconic film and novel have always been controversial. The story of a group of people centered around the fictional plantation Tara in Georgia on the eve of the Civil War, Gone with the Wind presents a sentimental view of the old South—and slavery. Contrary to what you might have assumed, there have always been people who took issue with the film.

A runaway success and in many ways the first "blockbuster," the film has become a fixture, so prevalent and so frequently parodied, referenced, and analyzed that it's become just part of the everyday scenery of American pop culture. But at a time of incredible change in the way the USA perceives both its past history of race relations and its path forward, it's impossible to ignore the messed up truth about Gone with the Wind—truths that include overt racism, love affairs, protests, and one of the most chaotic and poorly-run film productions in history.

The novel is even more racist

Many defenders of Gone with the Wind point to the fact that the film and the novel (which won the Pulitzer Prize) are nearly a century old, and obviously reflect what was considered culturally acceptable at the time. But as The AV Club notes, this argument would be more compelling if the novel presented its racism as an historical necessity. Instead, author Margaret Mitchell imbues much of the book with what is clearly her own attitude towards Black people, who are presented as sub-literate creatures and persistently described using standard racist templates.

Where the filmmakers were forced to keep some of the worst aspects of the book from the screen (The Washington Post notes that producer David O. Selznick insisted he would remove all racial bias from the story), Mitchell had no such problem. As Cass R. Sunstein writes for The Atlantic, the novel reads very much like an elegy for a civilization that Southern Belle Mitchell clearly admired—a civilization built on brutality, racism, and literal slavery. Several of her characters casually join the Ku Klux Klan, and in the novel Rhett Butler actually murders a Black man for the crime of speaking in an "uppity" manner to a white lady. And there is no hint that he suffers any consequences—or that he should.

Clark Gable took the role of Rhett Butler because he needed cash

It's safe to say that for modern audiences, Rhett Butler is Clark Gable's defining role. He's a brilliant character in many ways—a sarcastic, intelligent, self-loathing man who clearly sees the disaster coming for the South but steadfastly refuses to be a hero. While Gable wasn't the first choice for the role, he went on to own it with an iconic performance—once he was convinced to take it in the first place.

Not everyone thought the film was destined for greatness; a persistent rumor says that Gary Cooper passed because he was convinced the film would be a huge flop. And according to The Atlantic, Gable was also worried that he would never be able to live up to the expectations of readers who had already formed a mental image of Butler.

But as Rebbekka Wolton writes for Sports Retriever, Gable had other problems that the role could solve. Namely, he was embarking on a messy divorce from his wife, having fallen head over heels in love with Carole Lombard. His wife, Rhea Langham, was determined to make him pay through the nose for the privilege. Gable needed money, and that was the deciding factor in his decision to take the greatest role of his career.

There was rampant sexism on the set of Gone with the Wind

Gone with the Wind the novel, despite its repugnant racism, is actually a sophisticated and surprisingly modern take on gender politics that features a complex female protagonist. Gone with the Wind, the film, isn't quite as great in that respect, but Scarlett O'Hara is still depicted as a smart, fiercely independent woman for much of the story.

Sadly, behind the scenes things were a lot more like 1939 in terms of gender equality. In fact, Clark Gable, despite not being the lead in the film and not having nearly as much screen time as Vivian Leigh, got paid a whole lot more than his co-star. Granted, as The Atlantic notes, the studio had to overpay in order to get MGM to loan him out, but the discrepancy remains startling. According to TCM, Gable was paid $7,000 a week—which works out to an eye-popping $129,119 in today's money. Per week. And he only worked 71 non-consecutive days.

Leigh, on the other hand, had to work 125 days in a row, appeared in just about every scene, and was paid $25,000 total for her work—about $461,140 in today's money. Gable's total payout equals about $2.2 million in modern dollars, so about four times the pay for half the work.

Gone with the Wind's morality was flexible

At the time of Gone with the Wind's production, Hollywood operated under what was known as the Hays Code, a voluntary code of censorship designed to keep morally objectionable stuff out of films. This made some of the story elements a bit problematic, but it also extended beyond the plot and script, with producers worried about the reputations of the actors as well.

The casting process for the female lead, Scarlett O'Hara, was lengthy and used to drum up publicity for the film. Thousands of actresses read for the role, but in the end only two were considered strong enough to merit an actual color screen test—Paulette Goddard and English actress Vivian Leigh. As The Atlantic reports, Goddard was actually the favorite to win the part, but then it was discovered that Goddard was living with Charlie Chaplin, and the two didn't seem to be married. Worse, this was public knowledge. This was considered to be too risky for such an expensive production, and Goddard was dropped from consideration as a result.

Meanwhile, Vivian Leigh was involved in a torrid love affair with Laurence Olivier—who was very much married at the time. But since the extramarital affair wasn't publicly known, it didn't hurt Leigh's chances of getting the part.

Gone with the Wind's production was chaos

Gone with the Wind was an epic undertaking. At the time, it was the most expensive film ever made. Producer David O. Selznick bought the rights to the novel just a month after it was published in 1936 and spent two years in pre-production on the film. The Atlantic reports that Sidney Howard—who wound up with the sole credit for the script—turned in a first draft that would have run six hours long. Britannica notes that in the end Selznick called in no fewer than 13 writers—including author F. Scott Fitzgerald—to finish the job.

The film also went through at least three directors—George Cukor started the job but was fired three weeks into shooting and replaced with Victor Fleming. When Fleming was forced to take a break due to exhaustion (filming ran 140 days total), he was briefly replaced by Sam Wood.

Worse, the actors were temperamental. Clark Gable flatly refused to film the scene with Olivia de Havilland where he cries, afraid it would ruin his manly image. Only gentle coaxing from de Havilland got him to perform the scene as written. And Vivian Leigh, in love with Laurence Olivier, wanted very much to return home to England and so pushed to get as much filmed as possible every day, contributing to the sense of manic exhaustion on set.

They burned history for Gone with the Wind's most ambitious scene

According to The Atlantic, Producer David O. Selznick knew that star Clark Gable was available for a limited window of time. That meant that as 1938 drew to a close he had to get something on film in order to make it even theoretically possible to finish filming. He decided to go all in and film one of the two major set pieces of the movie—the burning of Atlanta.

As WQAD television reports, this single scene would cost $25,000 to shoot (about $450,000 in today's money) and would determine the fate of the whole project. If the scene turned out badly, there would likely be no recovering from the disaster. But since the scene could be shot without the actors (Gable wasn't available until February, and Scarlett O'Hara had not been officially cast yet) it was an ideal starting point. The production decided that in order to get the right sense of danger and scale, they would actually burn down some buildings. As History Daily notes, these structures were chosen from the studio backlot, and included many sets from classic films, including King Kong. In other words, a huge swath of Hollywood history was burned to the ground in order to get the shot.

The forgotten boycotts of Gone with the Wind

If it seems like the controversy surrounding Gone with the Wind is new, you just haven't been paying attention. Producer David O. Selznick was actually very aware of the controversial nature of the book's racism, and was determined to avoid it by ensuring a lack of "bias" in the film. But according to The Atlantic, the Black press wasn't convinced. As production began, Black newspapers like The Pittsburgh Courier threatened boycotts, as did the Los Angeles Sentinel.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) put pressure on Selznick as well, and The New York Times notes they strongly suggested that he signal he understood the concerns of the Black community by hiring technical advisers to ensure Black characters were represented fairly. Selznick did so—although both of the advisers he hired were white men.

As Newsweek reports, Selznick took all of this seriously enough to reach out to the Pittsburgh Courier. He informed them that there were no racial epithets in the script of Gone with the Wind, and that several objectionable sequences (including one featuring the KKK) had been removed. He also invited journalist Earl J. Morris to the set to meet with the Black actors. These efforts yielded much softer coverage from the newspaper, and the crisis was averted, for the moment.

Racism was okay, but keeping 'damn' took a lot of work

Gone with the Wind was filmed and released during a period in Hollywood where self-censorship was huge. During the 1920s, Hollywood dealt with a number of scandals, and in order to clean up its image it imposed the Motion Picture Production Code (known as the Hays Code after Will H. Hays, who helped set it up). Many aspects of Gone with the Wind were problematic in terms of the Hays Code.

You might think that the epic racism on display was one of those troubling aspects, but no one was particularly bothered by that outside of ensuring no actual boycotts were organized. Instead, two little words caused the film the most trouble. As Filmsite reports, the word "miscarriage" was given a hard no by the Hays office, and was replaced with the word "accident." And the other problem almost ruined one of the most famous lines in film history.

As Today notes, producer David O. Selznick knew that the line "My dear, I don't give a damn" (slightly reworked for the script) was important, and that the Hays office would resist. He wrote a lengthy justification for the inclusion of "damn" and "hell" in the script, getting into the semantics of whether "damn" counted as a curse as opposed to a simple "vulgarism." But as Elle Magazine reports, he played it safe by having writers come up with some alternatives—including the slightly less amazing "Frankly, my dear, I don't give a whoop!"

Racism marred everything to do with Gone with the Wind

Producer David O. Selznick was conscious of the racism in the material and made efforts to placate the Black community and ensure a lack of controversy. But he couldn't change the world, and the world in 1939 was decidedly pretty racist.

The film studio planned a lavish premier in Atlanta, and the city treated it like a national holiday. But Hattie McDaniel, the actress who would go on to win an Oscar for her role as Mammy, wasn't invited: As The Hollywood Reporter reveals, Georgia law at the time segregated theaters. This enraged Clark Gable, who'd become good friends with McDaniel during filming. Gable threatened to skip the premiere himself, but McDaniel—no doubt exhausted after a lifetime of dealing with stuff like that—politely informed everyone she couldn't make the event.

Worse, when McDaniel was nominated for an Academy Award, she wasn't allowed to sit with the white actors at the awards dinner. Selznick managed to pull strings to get her allowed into the main hotel to receive her award, however. Sadly for McDaniel, despite making history as the first Black actor to win an Oscar, she would never be fully accepted by the Hollywood establishment while also being reviled by many in the Black community for what they saw as willfully perpetuating Black stereotypes in the roles she took.

The infamous staircase scene

The relationship between Rhett Butler and Scarlett O'Hara is one of the best in literary history (we just wish it wasn't contained in such a blatantly racist book). He's a self-loathing schemer desperately in love with the young, beautiful Scarlett. She's the fiercely intelligent survivor clinging to the remnants of her old life. In many ways, they're using each other, but you almost feel bad for Rhett because Scarlett never stops loving another man.

Until, as The Washington Post points out, Rhett sexually assaults her. Haven't heard about that? Probably because when the film was first released the concept of marital rape wasn't widely accepted. In what is sometimes referred to as the Grand Staircase Scene, Rhett comes home extremely inebriated, angrily berates his wife for not loving him, and then grabs her and carries her to the bedroom while she struggles and protests.

Yeah. It's bad. Even worse, as Films Deconstructed points out, is the next scene, where Scarlett wakes up and is visibly happy about this event (pictured). But the characters are never depicted as being actually in love at this point—and its pretty clear that Scarlett isn't role-playing when Rhett grabs her. It's a disturbing element that just doesn't play well in the modern day—if it ever did.

Gone with the Wind is not very historically accurate

Gone with the Wind is historical fiction, but it's kind of bad at it. Although The Atlantic reports that author Margaret Mitchell claimed she'd spent "tens of years" researching the time period and historical events depicted or referenced in the book, she gets much of the reality of the Antebellum South wrong.

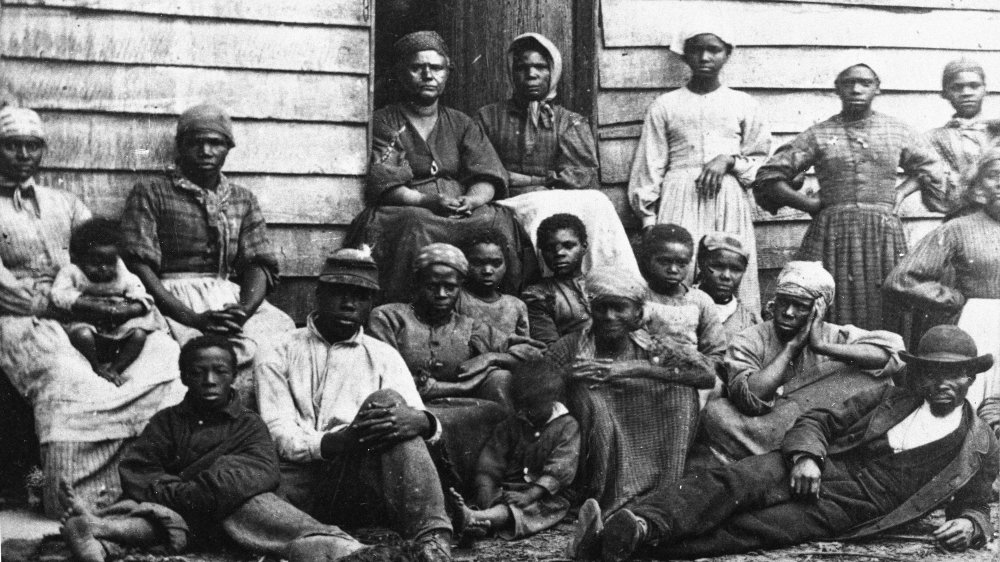

For one thing, none of the slave characters ever complain about their position, wish for freedom, or exhibit anything but affection for their white owners. For another, as Time points out, none of the white characters ever wrestle with the idea of slavery in any way. No one ever thinks to free their slaves, or that there might be anything at all wrong with owning another human being—in fact, Mitchell manages to avoid the problem simply by having O'Hara and other characters never even think about the larger issues of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Mitchell's greatest crime against history, as The Guardian points out, is making the Black characters in her book devoid of any inner life at all—they might as well be props. The only motivations, problems, or aspirations that matter in the novel and the film are those of white people.

The film is undeniably 'Lost Cause' propaganda

The Civil War decimated the former Confederacy, and it took decades for the region to recover economically and politically. As the 20th Century began, a revisionist version of history began to gain ground among many who longed for the good old days of slavery and white supremacy. They saw the Confederacy as a noble "Lost Cause," the Antebellum South as a glorious, peaceful society of beauty and grace, and the Civil War as a political dispute divorced from the issue of slavery.

There's little doubt that both Gone with the Wind and its film adaptation are essentially Lost Cause propaganda. As NY Mag explains, Mitchell purposefully romanticized slavery and made the life of a wealthy plantation owner in Antebellum Georgia look mighty wonderful, filled with spectacular dresses, handsome men, and lots of dancing. As The Washington Post explains, the story hits a major, common "Lost Cause" talking point in the depiction of Mammy and Pork. After the war is over, Mammy and Pork are free and no longer slaves. Not only do none of the white characters exhibit the slightest resentment of this fact, both characters volunteer to remain behind and continue to labor for their former owners—happily. That the slaves were actually well-treated and happy is one of the biggest lies of the Lost Cause, and Gone with the Wind pretends it was true.