The Biggest Scandals To Hit NPR

National Public Radio is America's 50-year-old public radio syndicate, a nonprofit media organization producing and distributing news and cultural programming for over 1,000 member stations.

Multiple millions of Americans wake up to NPR's flagship program Morning Edition and/or listen to All Things Considered on the drive home. Live shows like Wait Wait... Don't Tell Me! and A Prairie Home Companion have been touring the country for decades. But NPR's reputation has always veered to the bespectacled, bookish, and bland, and The Washington Post asked and answered, "Does NPR sound too 'white?'" (Yes.)

Hosts with uncommon names, off-kilter segments on all manner of subcultures, and a colloquial speaking style dubbed "the NPR Voice" have all contributed to an image of NPR as boring and unabashedly nerdy, so it may come as a surprise that even an outfit as vanilla as NPR is still frequently embroiled in scandal. Here are some of the biggest.

NPR drops World of Opera

World of Opera was typical NPR: opera performances from the world over interspersed with cultural and historical insights into the composers and performers, delivered in soft, dulcet tones. With episode titles like "A Baroque Variety Hour" and opera descriptions like "combines biblical and apocryphal gospel texts with deeply felt Latin-American poetry," the program was inoffensive at best. Airing on 60-odd stations around the country, World of Opera was as popular and as innocuous as they come, so it surprised many when NPR stopped broadcasting the program in 2011.

When it was reported that the show's host, Lisa Simeone, had been acting as a spokesperson for a group associated with the then-ongoing Occupy Wall Street protests, NPR decided to cut ties with World of Opera. Many of NPR's liberal listeners accused NPR leadership of caving in to people who "accuse NPR of somehow being a platform for progressive thought or Radio Moscow," as On the Media's Bob Garfield framed it in a conversation with outgoing NPR CEO Joyce Slocum. Slocum noted that NPR had ceased producing the show over a year prior and that NPR hosts represent the organization and have standards to uphold.

Simeone responded to NPR correspondent David Folkenflik: "What is NPR afraid I'll do — insert a seditious comment into a synopsis of Madame Butterfly?" World of Opera continued to be distributed by WDAV, the new producer of the show, until its 2016 cancellation.

NPR's CEO resigns following undercover video

Media bias is a trope so old that it's a functionally redundant phrase for a great number of people, which is partly why the media constantly reports on itself. (That narcissism may be common among writers.) From Yellow Journalism's Hearst and Pulitzer to today's Fox and MSNBC, some people see troublemakers where others see muckrakers.

A conservative "non-profit journalism enterprise" called Project Veritas released a secret recording in 2011 of NPR's top fundraising executive. He thought he was having a lunch meeting with two representatives of the "Muslim Education Action Center," which had offered NPR a donation of $5 million. They were actually working with Project Veritas, and they covertly filmed him calling the then-prominent Tea Party movement "not just Islamaphobic but really xenophobic [...] white, middle-America gun-toting [...] They're seriously racist, racist people." Predictably, Tea Partiers and the greater conservative political sphere erupted in righteous fury, proof in hand of the liberal bias they claimed permeated NPR. NPR Chairman Dave Edwards refuted the suggestion, telling USA Today, "We take very seriously, and we reject, the comments that were made in that video."

NPR's chief fundraiser and CEO both resigned immediately. The following week, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives voted to end federal funding of NPR, but it was rescued by the Democrat-controlled Senate.

NPR host fired for bullying, hostile work environment

Originally started as a one-time two-hour special the week of September 11, 2001, On Point is one of NPR's longer-running and popular call-in shows. For most of that time, one man was at the helm: Tom Ashbrook.

Ashbrook was well-respected by his peers and known as a fierce and opinionated host, described as "hands down one of the finest interviewers on radio and TV," by Mary Olson, general manager of one of largest public radio stations in California. When he was suspended in December 2017 and investigated by his employer, WBUR in Boston, for bullying as well as sexual misconduct, it shocked many. This was at the heyday of the #MeToo movement, and Ashbrook's friends, worried he was getting caught up in a "witch hunt atmosphere" that discredited the movement, penned an open letter in his defense signed by some prominent names in the press, arts, and academia.

Ultimately, WBUR fired Ashbrook for creating "an abusive work environment." Reporting on his dismissal, WBUR itself stated, "Devoted listeners called and emailed the station urging managers to rethink the decision and promising to go elsewhere if they didn't." On Point airs in over 290 stations around the country today, and the podcast is downloaded over two million times a month.

NPR's most popular host fired for #MeToo allegations

A Prairie Home Companion was one of the longest-running radio variety shows in American history. Generations of kids (whose parents listened to NPR in the car) grew up hearing tales of Lake Wobegon delivered with humor dryer than the Sahara during a drought. At its height, over four million people every week tuned in to almost 700 public radio stations around the country to enjoy a live comedy and music show chaperoned by the mellifluous voice and terrible dad jokes of Garrison Keillor.

The most successful Minnesota Public Radio star ever, Keillor also wrote several successful books and even starred in a celebrity-stuffed Hollywood movie adaptation of Prairie. His 2016 retirement episode was recorded live before 18,000 people and included a telephone call from President Barack Obama. As reported by The Irish Times, Obama told Keillor that "you kept me company. A Prairie Home Companion made me feel better and more human."

A year later, MPR announced they were cutting all remaining ties to Keillor amid an investigation into his workplace behavior. Allegations going back over a decade surfaced, and not only was Keillor fired, but A Prairie Home Companion was renamed. In addition, rebroadcasts of old episodes ended, and distribution of Keillor's daily program The Writer's Almanac was dropped. Keillor restarted The Writer's Almanac on his personal website, which also hosts old episodes of A Prairie Home Companion.

NPR's Israeli and Palestinian bias

Every news organization is accused of bias by someone or, depending on the subject, by everyone. Covering Israel, specifically any story about connections of that country with Palestine or anything remotely to do with Palestinians, is fraught with peril. Any sentence could be construed by someone as evidence of prejudice for or against ... something. Left-wing magazine Jacobin thinks the media industry is grossly pro-Israel. Conservative Aish Ha Torah, an Orthodox Jewish educational and news nonprofit with one of the largest Jewish content websites on the Internet, says that for everyone from The New York Times to the BBC, "the bias of most leading print and broadcast outlets against Israel has become entrenched."

NPR has been accused of biased coverage of Israel often, from both sides. In fact, in 2003, reported The Baltimore Sun, NPR's then-CEO attended the annual meeting of the Jewish Council for Public Affairs in order to "defend his network's coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict against charges of bias against Israel." The progressive media watchdog group FAIR has reported frequently over the years that NPR "takes a default pro-Israel line when reporting on the affairs of Israel/Palestine."

For its part, in 2014, NPR conducted a self-assessment over 11 years of its coverage on Israel and Palestine. They concluded that their coverage had a "lack of completeness but strong factual accuracy and no systematic bias." Which surely ended the question.

Former CEO accuses NPR of liberal bias

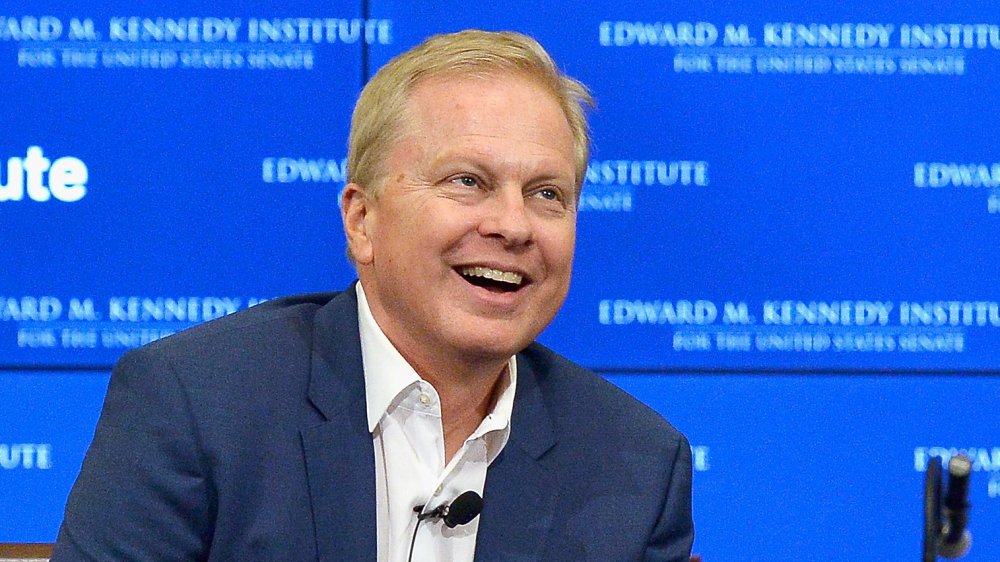

NPR takes accusations of bias seriously. They and their 1,000 member stations receive millions in federal funding, and NPR leadership refutes any suggestions that their coverage is slanted. So when former CEO Ken Stern released a book subtitled: "How I Left the Liberal Bubble," it caused a minor furor.

Stern's book gave anecdotal support for the conservative theory that America's press, and NPR specifically, is trapped in an ideological echo chamber. "Virtually everyone in the mainstream media is on one side of the political landscape," he told the CBC. His confessional wasn't well-received by many in the industry and generated a few indignant rebuttals from his former public radio colleagues. Stern's central thesis actually reflects well-established research. A Cambridge University study suggested that over 78 percent of American journalists are on the left. Investor's Business Daily reported the results of a twin university survey of American financial reporters (allegedly the most conservative type), revealing that fewer than five percent identified as conservative, compared to over 58 percent as liberal.

Writing in the New York Post, Stern warned that when everyone around you thinks the same, "it is easy to fall into groupthink." Preeminent pollster Nate Silver said it flatly in a postmortem on 2016 presidential campaign coverage: "There really was a liberal media bubble." Stern insists the full title of his book, Republican Like Me, doesn't reflect his actual sympathies, and he's registered as the largest US political affiliation: independent.

NPR fired a prominent black correspondent

A veteran and Emmy award-winning journalist with over two decades experience at The Washington Post, Juan Williams had been at NPR for ten years when they let him go for comments he made on a Fox News program.

Williams was a frequent guest on Fox, and in a late 2010 segment, he told host Bill O'Reilly that "when I get on the plane [...] if I see people who are in Muslim garb [...] I get worried. I get nervous." Backlash from Muslim groups, politicians, and fellow media personalities was swift, and NPR fired him. In a statement, NPR said that Williams' remarks "were inconsistent with our editorial standards and practices, and undermined his credibility as a news analyst with NPR." This wasn't the first time Williams had violated NPR's code of ethics, said NPR CEO Vivian Schiller in an internal memo reported by Politico, and he'd been "repeatedly asked to respect NPR's standards and to avoid expressing strong personal opinions on controversial subjects in public settings, as that is inconsistent with his role."

Backlash was equally swift against Williams' firing. Since he was one of the few prominent minority males at NPR, many were concerned with the optics of it."I fear some will look for racial motivations in NPR's decision to fire Williams," said NPR's Alicia Shepard. Williams landed on his feet, though. CBS reported that Fox News signed him to a $2 million multiyear deal.

NPR is elitist

NPR is public radio and depends on the public to survive. The regular and regularly annoying membership and donation drives cement that for even the most casual listener. You can't go too long without hearing that the program you just listened to is made by possible "by the support of viewers like you." But it turns out that much more of NPR's funding comes from corporations than from listeners or even from taxpayers.

In 2015, the progressive group Fairness and Accuracy In Reporting (FAIR) conducted a study and concluded that NPR is lopsidedly funded and directed by corporate interests. In an article titled "National Plutocrat Radio," FAIR described how "Corporate One-Percenters dominate NPR affiliates' boards." After studying the composition of the governing boards of the top eight NPR stations, FAIR said that three out of four NPR trustees is a corporate executive. The New York Times pointed out that the majority of NPR funding is in the form of corporate sponsorship and affiliate fees and not, as is their image, from individual listener contributions.

This is, in large part, strategic. NPR's audience has been shrinking for years, and the previous CEO made a concerted effort "to boost revenues greatly [...] by asking more — a lot more — of wealthy donors," which explains why the Times could report in 2020 that around one third of NPR revenue comes from corporate sponsors, although that number is falling.

NPR News chief resigns due to sexual allegations

Michael Oreskes (right) was an old-school journalist. He got his start in the New York Daily News before embarking on a 20-year stint with The New York Times and eventually settling down at NPR in 2015 as Vice President of News and Editorial Director. He didn't have a long tenure there. #MeToo was rough on NPR staff, and Oreskes was another installment in the network's purge of sexual predators in 2017.

The allegations against Oreskes stretched far before his time with NPR, all the way back to the 1990s. His case prompted a "virtual rebellion" among NPR staff, reported The Washington Post, in that NPR executives delayed addressing multiple sexual abuse accusations against Oreskes for nearly two years. According to the Associated Press, where Oreskes had also worked for a short period before joining NPR, Oreskes had already been chastised by NPR for a 2015 incident in which he made a female staffer uncomfortable.

Oreskes was asked to resign. The New York Times reported that he wrote a farewell letter to NPR staff in which he apologized, "I am deeply sorry to the people I hurt. My behavior was wrong and inexcusable, and I accept full responsibility." Oreskes received an unusually stiff dismissal, fired without severance or separation benefit, and WaPo reported that he also reimbursed NPR for $1,800 worth of expenses regarding the individual meetings he had with his accusers.

NPR producer in India resigns after anti-Hindu tweets

Furkan Khan was an NPR producer in New Delhi when she got Twitter-famous. Now, what you're about to read is offensive, but take in while you read it the breathtaking stupidity required to write this in the world's largest Hindu-majority country. On Twitter. As reported by the International Business Times, a journalist of an internationally respected media organization, in India, thought it was a good idea, in 2019, to tweet: "If Indians give up Hinduism, they will also be solving most of their problems what with all the piss drinking and dung worshipping."

Justifiably, and predictably to anyone who isn't a dribbling loon, outrage swiftly ensued. Organizations and individuals from India to London to California vented their fury at NPR. That the Indian ambassador to the United States had complained to The Week that same day about an anti-India bias in coverage of Kashmir in the American media definitely made things worse. Fellow Indian journalist Swati Goel Sharma suggested on Twitter that Khan's tweet "seems like a threat to Hindus around." NPR quickly issued a statement: "This comment does not reflect the views of NPR journalists and is a violation of our ethical standards. She has publicly apologized for her tweet and has resigned from NPR."

Khan did apologize, including, as reported by The Times of India, one very honest Tweet: "Please accept my sincere regret. I'll be off Twitter for a while."

NPR's diversity problem

NPR has had a demographic problem for a while. Their audience skews harshly upward in age, and that trend has been getting more pronounced. But other demographic problems have been plaguing the organization recently. NPR's audience is big, around 132 million monthly listeners across platforms they say, but it's also pretty white.

After the cancellation of one of NPR's few minority-run and aimed programs, due to sagging ratings, NPR's ombudsman, Edward Schumacher-Matos, lamented the lack of diversity at the organization. He pointed out NPR's audience and staff numbers were not in line with the national averages. Only ten percent of NPR's staff is black, and it's half that in their audience. In addition, five percent accounts for the number of Latinos on-staff and only six in the audience. NPR's education blogger added inadvertent context when she tweeted out on NPR's official Education Team account: "I reach out to diverse sources on deadline. Only the white guys get back to me." As WNYC's PJ Vogt summarized, "NPR has a diversity problem."

Schumacher-Matos explains that, "NPR appeals mostly to Americans with a college degree, regardless of race or ethnicity." If you take this into account, black and Latino listeners are in proportion with broader social numbers. And Asians are over-represented in the audience. NPR has made diversity a core mission over the last few years, and staff diversity has increased, from 77-percent white in 2014 to 71 today.

NPR bans torture from the air

In the late 2000s, the War on Terror was in full swing, America's military was surging in Iraq, the TSA was learning how best to pat down grandma, and we were all buying smartphones for the NSA to tap. America was also collecting prisoners detainees from all over the world to deposit in Guantanamo Bay and waterboard them for information. But was waterboarding torture?

Glenn Greenwald, an attorney-turned-journalist, accused NPR of banning the word "torture" from its descriptions of America's interrogation practices, calling NPR's ombudsman Alicia Shepard's explanation a "cringe-inducing montage of NPR's repeatedly going out of its way to avoid calling Bush interrogation tactics 'torture.'" NPR wasn't singled out — Greenwald aimed plenty of venom at The New York Times and many other outlets, accusing them of "complicity." Shepard disputed the characterization entirely: "NPR did not ban the word 'torture.' Rather, we gave our journalists guidance about how to avoid loaded language about interrogation techniques, realizing that no matter what words are chosen, we risk the appearance of taking one side or another."

In 2014, President Obama candidly admitted that "We tortured some folks," and The New York Times rescinded its own "torture ban," prompting NPR to clarify its own position on the matter: "Our guidance on use of the word "torture" comes down to the issue of whether it 'makes sense in the context of the piece.'" Which is just the most NPR way of putting it.