The Crazy True Story Of The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

In 1932, the US Public Health Service began conducting a study on the African-American men of Macon County, Alabama. While the men volunteered to be treated for "bad blood," they were never informed of the true nature or the risks of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.

For 40 years, public health officials engaged in unethical testing of Black sharecroppers, under the guise of offering them free medical treatment. But the men were never really given treatment. Instead, they were given placebos while researchers documented the long-term effects of syphilis on Black men, basing the foundation of their research largely on pseudoscience and eugenics. The medical mistrust sowed by the Tuskegee study would have lasting negative impacts on the African-American community for years to come.

According to Jean Heller, the reporter who eventually broke the Tuskegee experiment story, the men of Macon County were "strictly targets of opportunity. There was no humanity in this whatsoever. [...] They were just targets. They were just convenient guinea pigs," via "Bad Blood": The Tuskegee Syphilis Study.

"Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male"

In the 1920s and 1930s, public health was seeped in racial prejudice, and nowhere was it more apparent than in matters of sexual health. Dating back to the Civil War, scientists posited the idea that African Americans were a different species, and the negative effects of this harmful theory continued to influence scientific studies in America throughout the 19th century. By the turn of the 20th century, eugenics had surged in popularity in America, and scientists began presenting a series of pseudoscientific theories regarding the African-American population. Scientific and public health officials claimed that they had larger genitals and a higher sex drive than white people and were more prone to contracting sexually transmitted diseases, like syphilis, according to McGill University. Most crucially, scientists also believed that African-American men would not seek out or accept treatment for STIs even if they were available.

It was out of this climate of prejudice and racial bias that the infamously unethical "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male" was conceived.

Goal of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment

In 1932, Taliaferro Clark, the head of the venereal disease department of the US Public Health Service, designed an experiment that would study the course of untreated syphilis on Black men. While Clark is credited with founding the study, another doctor, Thomas Parran Jr., also played a significant role in beginning the experiment. The sixth US Surgeon General and a prominent Public Health Service official, Parran was a driving force behind the development and implementation of the study, per The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Parran was influenced by a similar study that had been conducted in Norway over 20 years earlier. "The Oslo study of the natural history of untreated syphilis," conducted between 1891 and 1910, was one of the largest studies on the effects of syphilis. Two thousand patients, both men and women, who had contracted syphilis were left untreated for nearly 20 years in Oslo, per Science Direct, to understand the natural effects the course of the disease would have on the human body.

The plan for the Tuskegee syphilis experiment was to build on that work, while also comparing the different effects syphilis might have on subjects of different races. Scientists believed that the cardiovascular systems of African Americans would be more significantly impacted by the disease. The initial purpose of the study was to examine the pathology of syphilis in African-American males for six to nine months, according to Britannica.

"Black Belt"

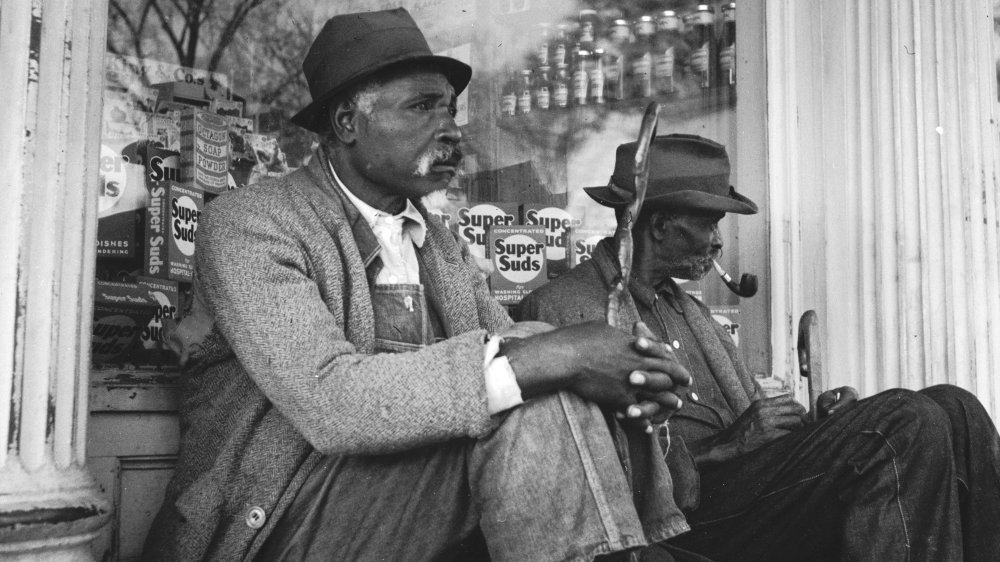

US Public Health Service officials needed a location to conduct their study, and they found the perfect place in Macon County, Alabama. It was known as the "Black Belt" of the region, both because of the thick, dark soil that made land so fertile for agriculture and because of the large population of Black sharecroppers who made their living working the land, according to Tuskegee University. According to the US Census, 82 percent of Macon County's population was Black in 1930, per "Bad Blood." The region was very rural, and most sharecroppers were not well-educated. In Macon County, 227 out of every 1,000 African Americans could not read.

A predominantly rural, Black, and illiterate population was ideal for the purposes of the Tuskegee experiment. In January 1932, after seeing Macon Country, Dr. Parran declared, "If one wished to study the natural history of syphilis in the Negro race uninfluenced by treatment, this county would be an ideal location for such a study," via The Philadelphia Inquirer. Dr. Clark echoed a similar sentiment, saying: "Macon County is a natural laboratory; a ready-made situation. The rather low intelligence of the Negro population, depressed economic conditions, and the common promiscuous sex relations not only contribute to the spread of syphilis but the prevailing indifference with regard to treatment."

Almost 40 percent of Tuskegee's Black population had syphilis

Tuskegee also had one other major factor that made it the perfect location for the experiment: Almost 40 percent of the Black population of Tuskegee had syphilis by 1929, making it the city with the highest syphilis infection rate in the country, according to Time.

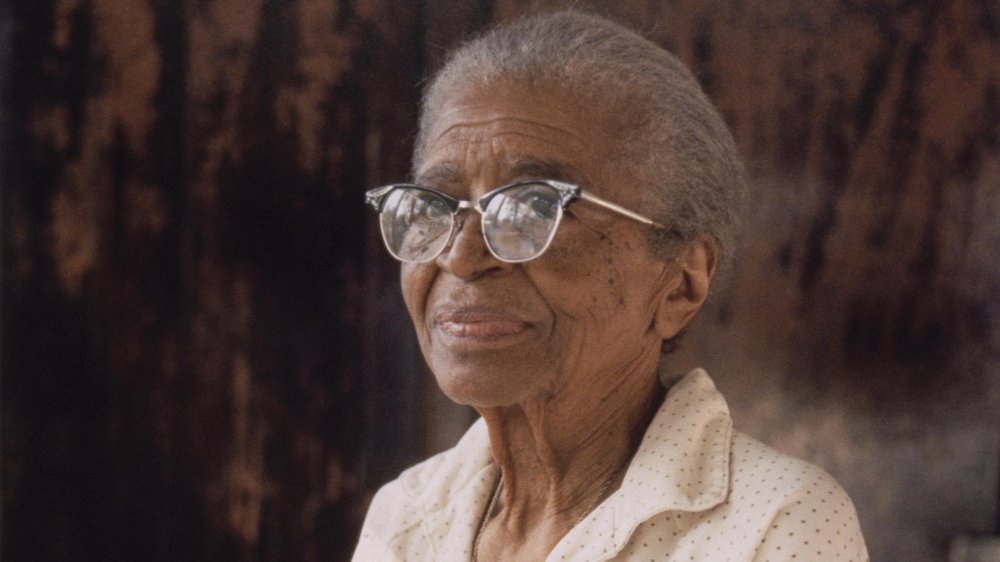

The US Public Health Service enlisted the help of the Tuskegee Institute, now known as Tuskegee University, and its affiliated hospital to conduct the study. They also enlisted Eunice Rivers, a local nurse, to help establish trust within the community, according to The Washington Post. Rivers (pictured above) was charged with helping pick up subjects and bring them to their appointments, deliver hot meals, and drop off medicine, but behind the scenes, she was also in charge of keeping records on the men. She also reached out to surviving family members after a subject had passed to encourage them to consent to autopsies. Rivers served as a critical point of connection between the researchers and Macon County's African-American population for the entire 40 years of the study.

Tuskegee subjects were compensated with free food and medical exams

Health officials initially recruited subjects to the study by offering them free medical care. Macon County was not a wealthy region, and health care was not always easy to come by for Black agricultural workers, so it was an enticing offer. However, some men were initially skeptical, suspecting that they were really being examined for military recruitment. To quell these fears, officials began including women and children in their examinations while still adding any eligible men they encountered to the study, according to McGill University.

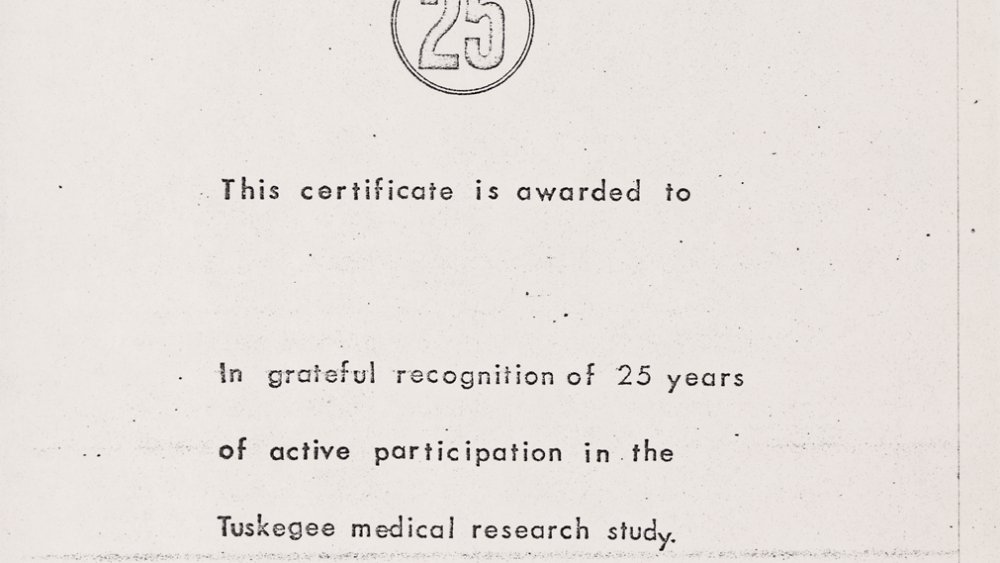

In the 1930s, as the Great Depression worsened, the promise of free medical care was an exceptionally temping offer, particularly for an economically impoverished area. However, even the promise of free health care was not enough to entice some of the men to continue the treatments. So as the study went on, the subjects were offered more benefits, including extended medical treatment, free rides to appointments, hot meals on appointment days, medical exams, and even burial stipends, per Tuskegee University.

For some of the treatments, like the painful and ultimately unnecessary spinal taps, Public Health Service officials used a psychological tactic. Enticing them with the offer of a "special free treatment" for their "bad blood," officials convinced many of the men to undergo the dangerous spinal procedure, according to The New Social Worker.

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment went on for 40 years

The original experiment was only supposed to last six to nine months. Initially, the patients were left untreated for around six months and then treated with heavy metals, like arsenic, bismuth, and mercury, per Britannica, which were commonly used therapies at the time. However, the study subjects were largely only given treatment in order to abide by Alabama guidelines and assuage any fears on the part of the participants.

Researchers released their initial findings in 1934 and published their major paper on the experiment in 1936. However, that same year, researchers declared that they hadn't received enough data and decided to extend the study. Rather than treat the subjects, they chose to follow the infected patients throughout the rest of their lives, documenting the long-term effects of the disease, according to the CDC.

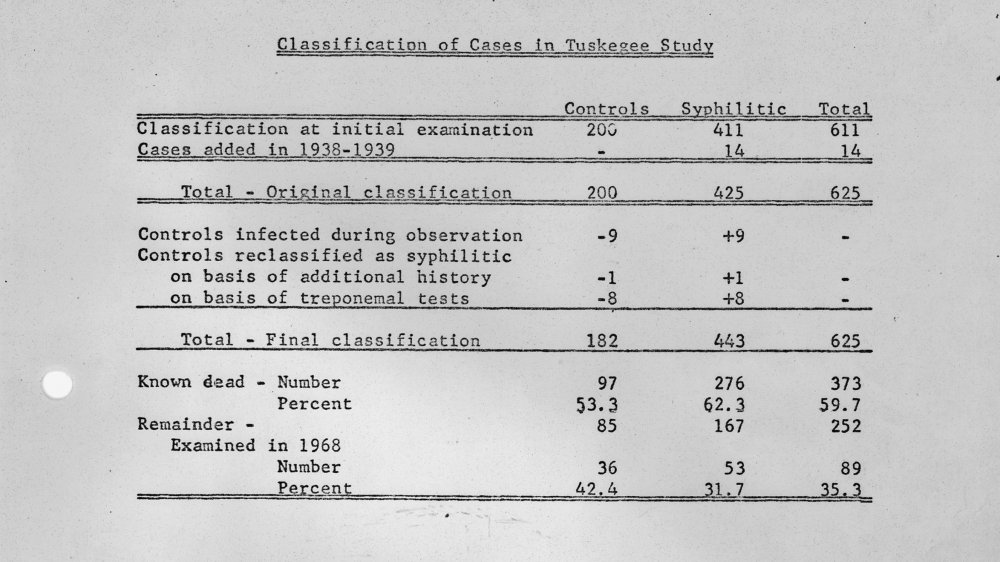

Initially, they'd recruited 600 Black men to the study, of whom 399 had syphilis. The remaining 201 African-American men who didn't have the disease served as the control group. All of them were then given placebos to continue the ruse that they were being treated, while in reality, none of them were receiving proper medical care. The study went on for 40 years, and when it finally came to an end in 1972, only 74 of the subjects were still alive, per The New Social Worker.

Informed Consent

One of the main reasons the Tuskegee experiment was so unethical was because the study participants were never provided enough information to be able to give their informed consent. In fact, researchers deliberately withheld information about their disease and the true purpose of the experiment. An intern at the Tuskegee Institute's hospital admitted, "The people who came in were not told what was being done. We told them we wanted to test them. They were not told, so far as I know, what they were being treated for or what they were not being treated for. [The subjects] thought they were being treated for rheumatism or bad stomachs. We didn't tell them we were looking for syphilis. I don't think they would have known what that was," via "Bad Blood."

The subjects were told only that they were being treated for "bad blood," which could include any number of illnesses, from syphilis to anemia to simple fatigue. None of the subjects were told they were being treated for an STD, and as a result, many unknowingly passed it on to their wives or girlfriends. Because they were not aware what illness they were being treated for, subjects were also not given the option to leave when penicillin became readily available as a syphilis treatment, per the CDC. None of the patients were informed of the potential dangers, and none ever gave informed consent, making the Tuskegee syphilis experiment one of the most notorious and unethical studies in American history.

Researchers withheld treatment from Tuskegee subjects

When the study began in 1932, there was no known cure for syphilis. However, the study's subjects were repeatedly denied even the minorly effective treatments that were commonly used at the time, like mercury or arsenic.

In 1947, it was determined that penicillin was an effective cure for syphilis, and by the 1950s, it had become the standard treatment and was widely used. Despite knowing this, officials never gave the study subjects penicillin to treat the disease. As a result, 128 of the men died from syphilis or its complications, 40 of their wives were infected, and 19 of their children had the disease passed down to them over the course of the study, according to McGill University

Study officials went out of their way to ensure that subjects were not treated. In 1934, officials provided all doctors in Macon County a list of study participants, telling them not to treat the subjects. In 1940, they expanded the distribution of the list to the Alabama Health Department. The following year, when some of the subjects were drafted to the Army, their medical entrance exam revealed the disease. Researchers, instead of allowing the men to be treated by Army doctors, pulled the men from the Army. The staff nurse, Eunice Rivers, even once followed a study subject to his personal doctor to ensure that he was not treated for syphilis, per The Washington Post.

A whistleblower brought the Tuskegee syphilis experiment down

No one raised any concerns about the unethical nature of the study until 1966, when Peter Buxtun, a Public Health Service employee, became suspicious after hearing that a colleague in the venereal disease section had scolded a doctor for treating a Tuskegee study subject with penicillin.

Upon further investigation, Buxtun was shocked to discover the similarities between the syphilis experiment and the crimes that had been brought to court during the 1947 Nuremberg Doctors' Trial. The subsequent Nuremberg Code had been established to prevent unethical experimentation on human subjects, but these ethical guidelines were being steadfastly ignored in the Tuskegee study.

Buxtun wrote a report detailing his concerns about the unethical nature of the experiment, but his report was dismissed by his superiors, who insisted the subjects were all "volunteers." Buxtun argued they were "nothing more than dupes ... being used as human guinea pigs" and were "quite ignorant of the effects of untreated syphilis," via the Government Accountability Project. When the US Public Health Service chose to continue on with the study, Buxtun decided to go public. He leaked information about the experiment to Jean Heller, a reporter at the Washington Star, who broke the story July 25, 1972. The ensuing public outcry over the unethical nature of the study led to its eventual end in October 1972.

Public outcry

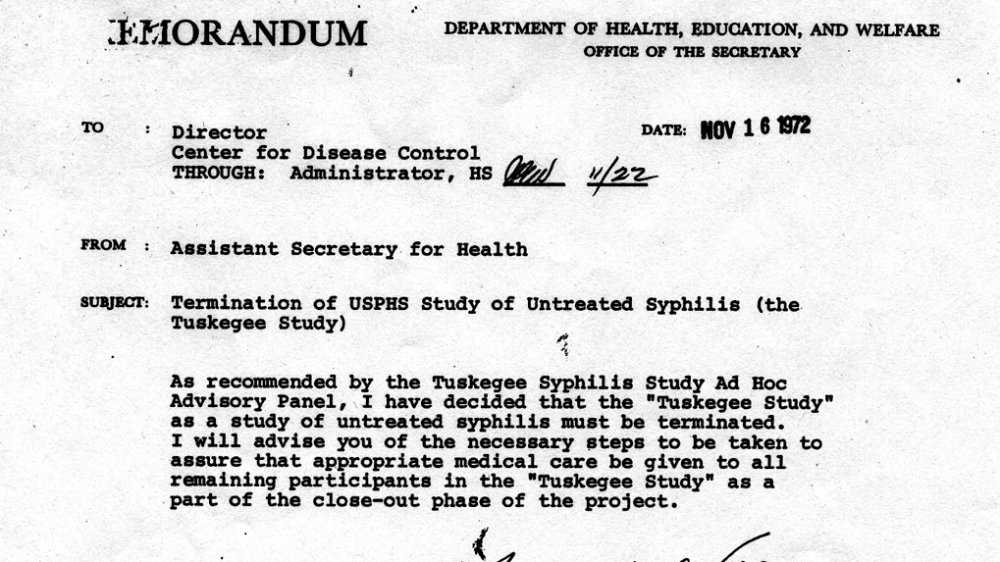

After the Tuskegee story broke, public outcry was immediate. Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy called the experiment "outrageous and intolerable," according to the Government Accountability Project, and held congressional hearings on the matter. An advisory panel was also established to review the study, and in October 1972, the panel ruled that the study was unethical and should be stopped immediately, officially bringing the 40-year experiment to an end.

The study's surviving participants, represented by attorney Fred Gray, filed a class-action lawsuit against the US Public Health Service in the summer of 1973, per Tuskegee University. The study's remaining subjects were awarded a $9 million settlement. They were also granted lifetime medical benefits and burial services. In 1975, the benefits were extended to include not just the surviving subjects, but all participants' wives and children, as well. In 1995, it was extended one final time, to include health as well as medical benefits for all participants and their families. The Tuskegee Health Benefit Program was established to disperse the benefits, according to the CDC.

Congress also passed additional protections for human subjects, including the National Research Act, which required the approval of institutional review boards for all experiments using human test subjects, according to Britannica. The outcry following the Tuskegee syphilis experiment helped establish many of the modern medical ethical standards that are in place today.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee

In 1994, a symposium called "Doing Bad in the Name of Good?: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Its Legacy" was held at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library in Charlottesville, Virginia. The goal of the symposium was twofold: First, they wanted a public apology from the president on behalf of the government for the experiment, according to Tuskegee University. They achieved this goal on May 16, 1997, when Bill Clinton publicly apologized for the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, saying, "You did nothing wrong, but you were grievously wronged. I apologize and I am sorry that this apology has been so long in coming, " via Time.

Their second goal was a little more complicated. They hoped to address the lasing damage of the study and set up strategies to address unethical government studies while restoring the reputation of Tuskegee University. The result was the creation of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee, which first convened in January 1996 and focused on establishing scientific ethics, as well as the founding of Tuskegee University's National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care.

Lasting public health effects of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment

In the aftermath of the tests, African-American communities developed a mistrust of public health initiatives that still lingers today. As a result, Black men are less likely to seek health care and treatment than their white counterparts, per The Atlantic.

According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, a study "comparing older black men to other demographic groups, before and after the Tuskegee revelation, in varying proximity to the study's victims" found "that the disclosure of the study in 1972 is correlated with increases in medical mistrust and mortality and decreases in both outpatient and inpatient physician interactions for older black men."

After the experiment had been made public, life expectancy for Black men at age 45 fell up to 1.5 years. The Tuskegee syphilis experiment continued to cause harm to the Black community even years after it officially ended.