The Disturbing Truth Of Company Towns

It may seem like the main objective of Monopoly is to last forever and make the other players hate you until the end of time ... but in a way, the aim is to create a lucrative company town. You strategically buy up properties, railroads, and utilities, until you have the most money, and control pretty much every residence, place of employment, and important resource in that infuriating universe.

In this infuriating universe, megacorporations play their own games of Monopoly using rules they write. IBM established its first headquarters in the village of Endicott, New York, which transformed into a company town. Guardian contributor Heidi Moore writes that at its height Endicott had roughly 13,000 residents, 11,000 of them IBM employees. By 2014, the company had laid off more than half the staff to placate Wall Street investors. In 2020, Facebook revamped plans to build its so-called Willow Village in Silicon Valley, which would house thousands of employees, per Mercury News.

Other juggernauts have created de facto company towns. For instance, in Seattle, Washington, Amazon amassed "as much office space as the city's next 40 biggest employers combined," according to a 2017 Seattle Times piece. Notably, Amazon founder, majority shareholder, and modern-day robber baron Jeff Bezos also owns the Washington Post, founded the aerospace manufacturer Blue Origin, and is the world's wealthiest man, via Investopedia. Historically, such arrangements have given employees ample reason to hate the players and the game.

Taking the Lowell road

Smithsonian Magazine names Lowell, Massachusetts as America's very first "truly planned company town." Named after Francis Cabot Lowell, it was a textile town founded in the 1820s after his death and modeled after his life philosophy. Per History of Massachusetts, biographer Chaim Rosenberg describes Lowell as "wealthy from birth and sheltered from the roughness of life." Convinced failure is born of "personal weakness" while hard work breeds success, Lowell wanted to create a factory utopia where workers could live in company-owned homes, eating company-provided food.

The primarily female workforce in Lowell awoke to factory bells at 4:30 in the morning and had twenty minutes to clock in. They were also required to attend church. The hope was that these employees would flourish through strenuous effort and strength of character "rather than form a permanently downtrodden underclass." Yet increasing hours and decreasing wages created a low-paid, overworked underclass of immigrants who were valued for their willingness to do more for less.

A game of life and death

When a company writes the rules, they have every incentive to rig the game in their favor. In the 19th and 20th centuries, workers who tried to rewrite those rules were occasionally met with massacres. As Smithsonian Magazine details, in 1897, miners in the coal town of Lattimer, Pennsylvania, went on strike after a supervisor struck one of them with a hand ax to promote of "work discipline." Not long after, roughly 400 foreign-born workers —some of whom already received 10 to 15 percent lower wages than so-called "English speakers" — started a peaceful march to protest a pay cut that was imposed to offset a new tax.

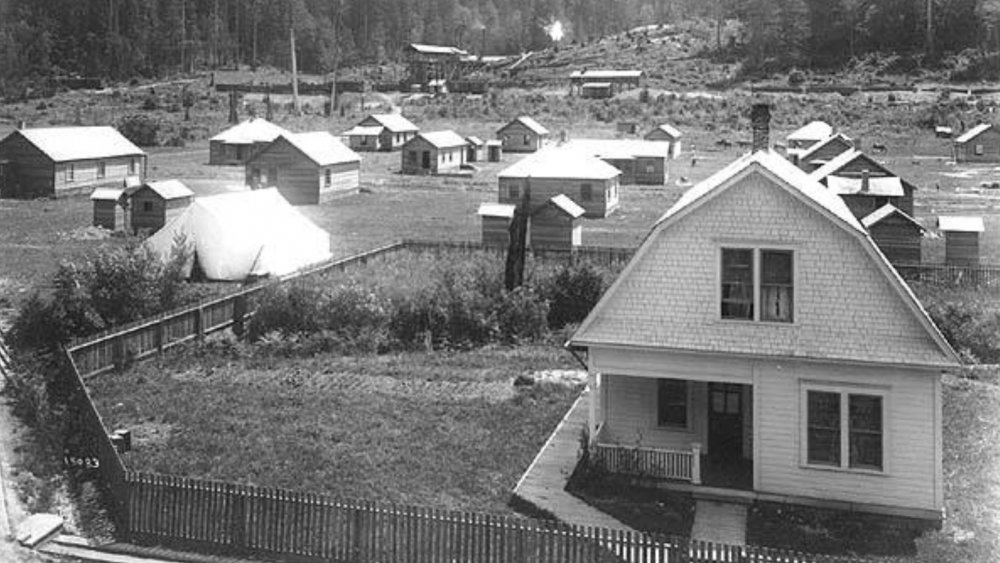

Lattimer's peaceful protesters were greeted by hostile sheriff's deputies, who harassed them. Tensions escalated, pitting the protesters against 86 armed deputies, who were accompanied by coal police. Nineteen miners were shot dead. Perhaps the most infamous company town massacre took place in Ludlow, Colorado. The town was run by Colorado Fuel and Iron company, which belonged to the world's first billionaire, J.D. Rockefeller. The resident miners grappled with black lung, carbon monoxide poisoning, explosions and cramped conditions, per Moyer on Democracy.

Ludlow's serf-like workers were evicted from their company-owned homes for trying to strike, forcing them to live in tents, according to Timeline. The company's hired guns shot into those tents as families slept. Because some miners fired back, the National Guard was called in. The ensuing 10-day conflict ended in some 75-to-100 deaths.