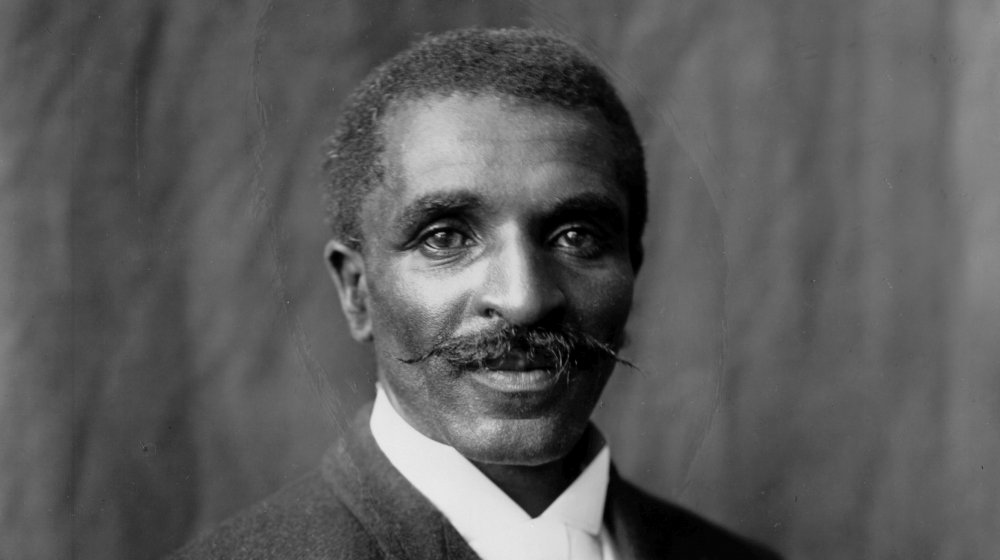

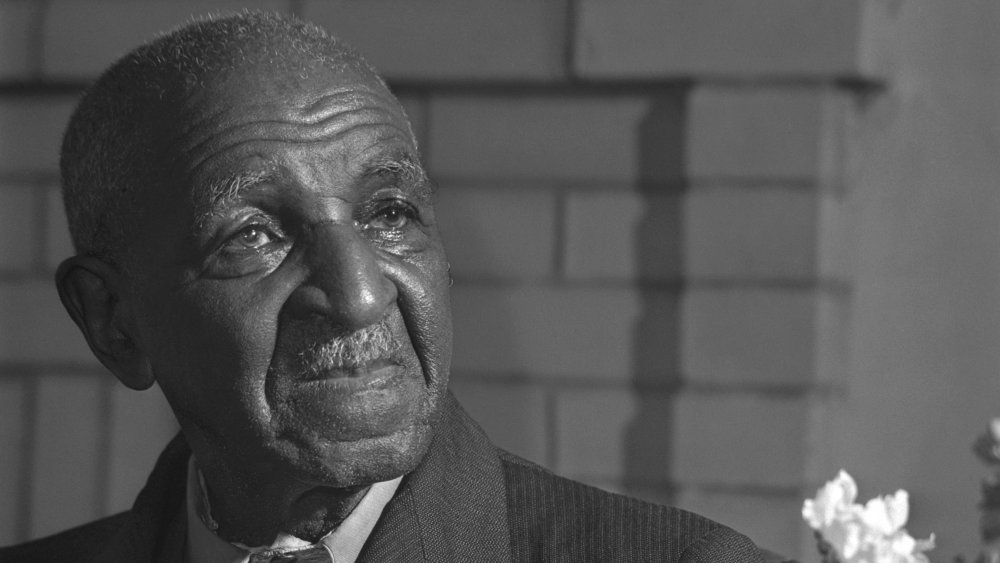

The Untold Truth Of George Washington Carver

Many know George Washington Carver as "that peanut guy." However, this hardly scratches the surface of the prominent 20th-century scientist and agriculturist. George Washington Carver is, after all, a household name. NPR described Carver as "The Black History Monthiest of Them All." It's true — most children get their introduction to George Washington Carver through flash cards and book reports during the month of February.

So, what is Carver known for? Contrary to popular belief, the legume-happy Carver was not the inventor of peanut butter. (Peanut butter use can actually be traced back to the Aztecs and the Incas.) George Washington Carver can more accurately be credited as the implementer of crop rotation, the first Black student (and later faculty member) at what is today the Iowa State University, and one of the earliest proponents of the sustainability movement.

Carver's climb to academic prominence was a challenging one, though. His early life was one of immense loss, liberation from slavery, and setbacks due to the racist policies governing the era. This is the untold truth of George Washington Carver, the squeaky-voiced botanist who rose from the institution of slavery to become the foremost agriculturist of 1900s America.

George Washington Carver was enslaved at birth

George Washington Carver, enslaved at birth, was born in Diamond, Missouri, sometime in the 1860s, toward the end of the Civil War. Young George's mother, Mary, was enslaved by Moses and Susan Carver. It's suspected that George's father was an enslaved man on a nearby farm who was killed before he was born.

As noted by the State Historical Society of Missouri, an infant George Washington Carver, along with his mother and sister, were kidnapped by Confederate raiders. This band of raiders was associated with men who roamed Missouri during the Civil War era with plans to sell captured enslaved workers for a profit. Moses Carver's neighbor reclaimed George and brought him back to the farm. Tragically, George's mother and sister were never heard from again. Freed after the passing of the 13th Amendment, George then was raised by the Carvers along with his older brother Jim.

George Washington Carver becomes the Plant Doctor

George Washington Carver proved himself to be a most unusual child. Moses Carver's wife, Susan, taught George to read and write, and soon enough, Carver was consumed by a love of learning. On the Carver farm, young George, enfeebled by whooping cough, took on domestic chores such as cooking, laundry, and gardening. A devout Christian, Carver had faith that his health would improve. Carver also developed a complete fascination with painting, algebra, music, and most of all, flowers.

In an account by Carver himself, collected by the National Park Service, he described flowers as his pets and said "all sorts of vegetation seemed to thrived under my touch." With his green thumb, Carver was dubbed "the Plant Doctor" by those who knew him.

Though the Carvers had allowed George to study at home, at the time, public schools were not open to Black children. But there was an all-Black school in Neosho, where Carver boarded for two years in the late 1870s. Carver bounced around the Midwest, using his domestic skills to fund himself, and finished out his high school degree. When George Washington Carver was accepted to Highland College in Highland, Kansas, the offer was rescinded as soon as the college discovered that he was Black.

George Washington Carver gets in the classroom

In the late 1880s, Carver moved to Winterset, Iowa, and became a cook at a large hotel. It was here that he made friends with the white couple John and Helen Milholland, as told by the State Historical Society of Missouri. The couple pushed Carver to enroll at Simpson College to study art and piano. Funnily enough, Carver's art teacher, Etta Budd, saw a burgeoning botanist in her student and encouraged him to transfer fields, according to The Henry Ford. Taking her advice, the next year, Carver moved to State Agricultural College at Ames, Iowa, to study agriculture.

George Washington Carver was able to utilize his keen artist's eye in the field of horticulture, contributing his own drawings of plants to botanists. In fact, Carver's painting "Yucca and Cactus" won an honorable mention at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, per Tuskegee University. In 1894, George Washington Carver earned a bachelor of science degree and became a faculty member at Iowa State. Carver then got his master's in agriculture, graduating in 1896.

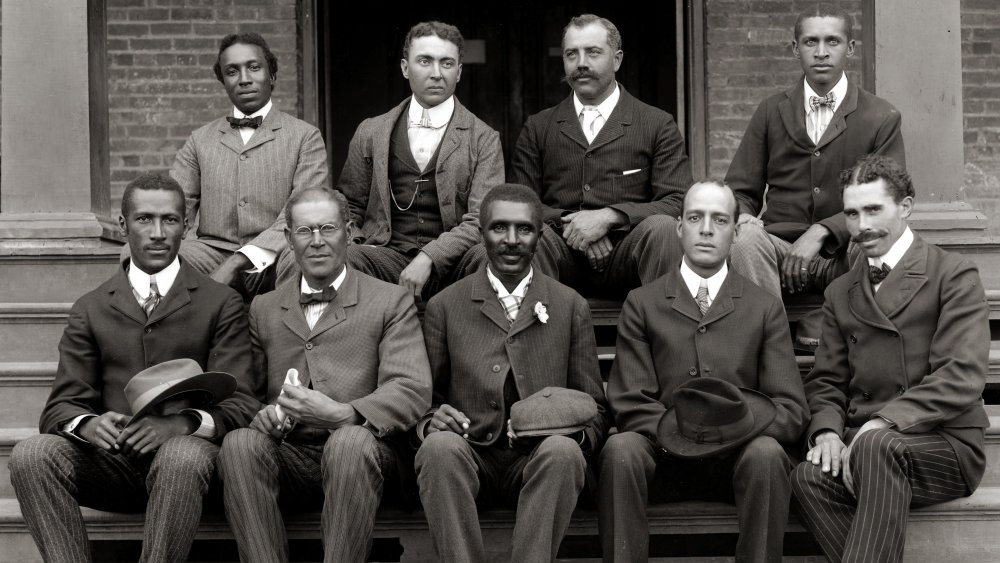

George Washington Carver joins the Tuskegee Institute

With accolades and degrees, George Washington Carver was scooped up quickly for a career in agriculture. On October 8, 1896, Booker T. Washington recruited Carver to teach agriculture at the Tuskegee Institute and serve as the department's director.

Carver's role at Tuskegee was a bit unusual. (Sensing a trend?) Carver, who remained unmarried for his whole life, had special perks as a professor. Washington allowed Carver to take up residence in two dorm rooms, one for his plants and one for him, whereas two single professors usually shared one room. According to the American Chemical Society, Carver was paid $1,000 a year, compared to his colleagues' roughly $400 average. Sometimes, though, Washington and Carver clashed. As told by NPR, Carver could be somewhat of a diva: Though beloved by students, he often threatened to resign and hated paperwork. At one point, Carver — who only wanted to be tinkering in his lab — asked Washington if he could stop teaching students. Washington refused him, but his successor, Robert Russa Moton, allowed Carver to cut back on classes except for summer school in 1915.

Carver stayed at Tuskegee until his death in 1943, and in his later years, he largely pivoted to experimentation, public speaking engagements, and chronicling his research. Carver was said to work excruciating hours — sometimes 4:00 AM to 9:00 PM – researching agriculture.

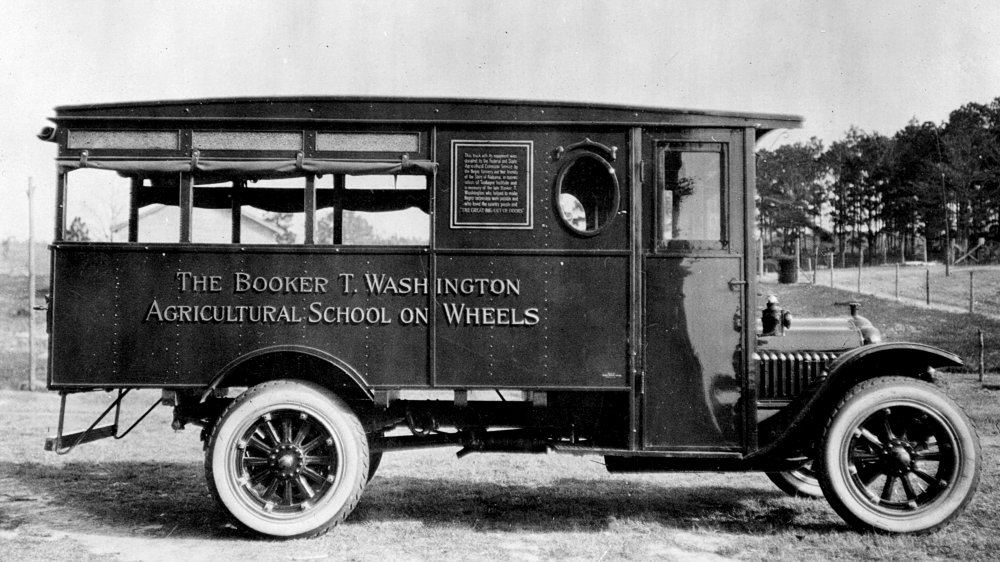

George Washington Carver opens a school on wheels

For George Washington Carver, teaching agriculture was a means of uplifting African Americans. He wrote: "It has always been the one great ideal of my life to be of the greatest good to the greatest number of 'my people' possible. [...] This line of education is the key to unlock the golden door of freedom to our people," as reported by ACS.

Arriving in Alabama to teach at Tuskegee, Carver was struck by how the monoculture of cotton had depleted the soil and caused erosion. As was the system of sharecropping at the time, Black farmers were using Southern landowners' plots and forced to give those owners a piece of the pie. Because Black farmers rarely owned their own land, they weren't investing in the quality of the soil.

At Tuskegee, George Washington Carver launched the Jesup Agricultural Wagon, a sort of mobile school, to deliver tools and do demonstrations for rural farmers. Starting in 1906, the Wagon taught about 2,000 people a month, per Smithsonian Magazine. With his school on wheels, Carver was able to teach Black farmers how to compost and grow their own food. Carver was introducing a method of social progress outside of the warped Jim Crow system — the Jessup Wagon was a means of teaching liberated Americans to meet all their needs through tending their land.

George Washington Carver revolutionizes agriculture

As George Washington Carver had discovered in his research, the South's cash crop, cotton, was depleting the soil. To solve this, he developed a system of crop rotation, which worked by using enriching plants like soybeans, pecans, peanuts, and sweet potatoes to reinvigorate the soil on Southern farms, as ThoughtCo notes. When the land reverted back to a cotton crop, the yield was that much greater. The method was so solid that Carver was able to transform a half-acre plot from a yield of 40 bushels of sweet potatoes to 266 bushels in only a matter of years, according to ACS.

It was also in these Tuskegee years that George Washington Carver became the peanut champion. He discovered that peanuts could be grown as a companion crop to cotton because they grew at different times of the season. Peanuts were a key pick because they produce their own nitrogen, which enriches the soil they are in. Not to mention, peanuts are highly caloric, full of protein, and nutritious.

With Carver's focus on economic recovery for poor Black farmers, all of his growing tips — which he published through 44 bulletins – were replicable for one-horse farmers with limited equipment and no access to commercial fertilizer.

George Washington Carver helps the war effort

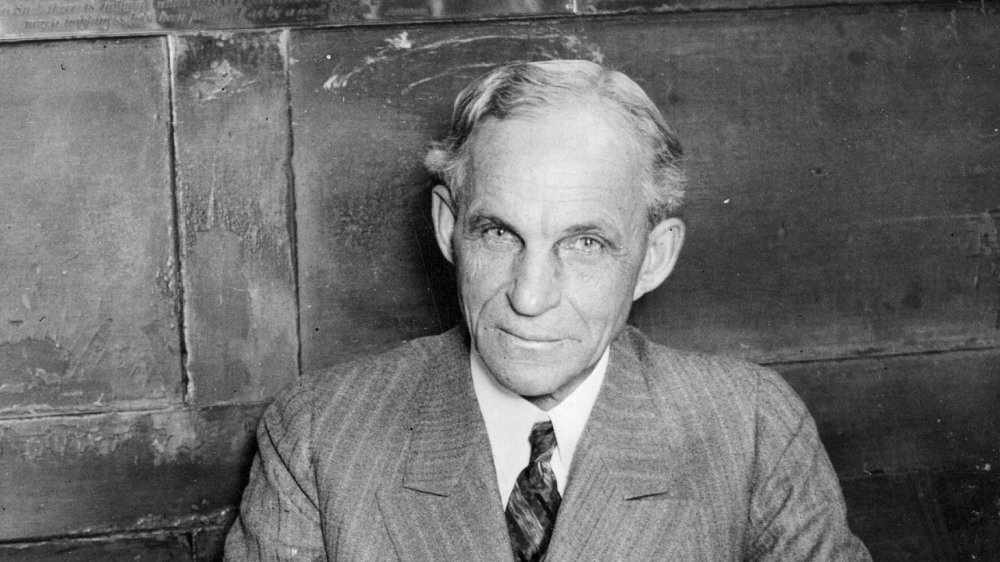

During World War I, George Washington Carver was asked to help fellow innovator Henry Ford — a friend of Carver's — with developing new products to help the resource-hungry country. Carver assisted Ford in developing a rubber substitute using, what else, the peanut, according to Live Science. During this period, dyes from Europe were also difficult to track down. Carver set to work developing over 30 variations of dye colors, all made from Alabama soils.

The First World War also brought a wheat shortage, so Carver began developing a way to make flour from dried sweet potatoes. This piqued the US Department of Agriculture's interest, per How Stuff Works, and they drew up plans for large-scale experiments to test Carver's sweet potato flour. The wheat shortage, luckily, didn't last long once the war resolved, so none of us are still going to the store to pick up a bag of sweet potato flour. Carver's inventive war effort had illustrated something that he had always believed: "Learn to do common things uncommonly well; we must always keep in mind that anything that helps fill the dinner pail is valuable."

George Washington Carver testifies in Congress

So, how did George Washington Carver officially become the peanut man? In 1921, he was asked by the United Peanut Association of America to go to Washington, DC, to give a talk in front of the US House Ways and Means Committee about peanuts. Congress had been debating a tariff on foreign peanuts, and Carver stood up to testify. Congress was surprised by the breadth of knowledge he shared about the legume and floored by its many uses, as reported by Smithsonian Magazine.

When one member of Congress made racially tinged jokes about George Washington Carver craving watermelon, Carver politely deflected that watermelon was a dessert food, per NPR. He proceeded, barreling through time extensions on his testimony. Congress was so rapt that they applauded when Carver was finished. In the end, the tariff on imported peanuts that Carver was lobbying for was passed. This was exceptional within the context of America at a time when Jim Crow laws, Plessy v. Ferguson, and the Ku Klux Klan were the law of the land. Carver was one of the few Black men who had a mainstream presence in American culture. This Congressional appearance would skyrocket his public profile.

George Washington Carver was incredibly famous

During his lifetime, George Washington Carver was the most famous Black man in America. In 1941, Time magazine named him the "Black Leonardo." This was a man who had many buildings and institutions — like a theater in Norfolk, a swimming pool in Indianapolis, and a professional building in Cincinnati, to name a few — named after him, according to NPR. Carver had a high, squeaky voice and a humble, excited demeanor that enthralled his audiences and students alike.

Still, George Washington Carver was a Black man in the early 20th century, so he was constantly navigating a world of accommodation and separation within his fame. Once, while dining at Henry Ford's house, Carver slipped out to eat his meal outside so that he wouldn't offend any white guests.

In the 1930s, Carver arrived at a New York hotel with a room reservation, only to be dismissed when he attempted to enter. Even when pressed by white colleagues, the hotel still would not admit Carver. This was common for him. When George Washington Carver spoke at hotel engagements, he was used to side entry and eating in the kitchen, per the National Park Service.

George Washington Carver's 300 uses for peanuts

After singing the praises of the peanut crop, George Washington Carver met some backlash: Southern farmers were thrilled with their thriving cotton crop but had way too many peanuts on their hands. So Carver set to work thinking of ways to use that surplus, as told by Live Science. The result was 300 new peanut products, which Carver introduced to the public in a series of brochures.

George Washington Carver was using the peanut for everything. According to the Tuskegee Institute, his inventions include flour, meat substitutes, paste, insulation, laundry soap, shaving cream, peanut orange punch, laxatives, wood stains, printing ink, and antiseptics.

While peanut butter was certainly on George Washington Carver's list of peanut uses, he never claimed it was of his own invention. In fact, many of Carver's product ideas were borrowed from magazines and cookbooks of the day, which he acknowledged by citing over 20 sources within his brochures, notes Smithsonian Magazine. Carver's aim was not to invent peanut products or even take credit for them with patents but to show poor farmers that their new abundance of peanuts was an economic win. In fact, Carver didn't even think his work with the peanut was the most important of his life — it's just the one that stuck.

George Washington Carver's odd jobs

George Washington Carver's work wasn't just limited to the fields and his lab. He took on other pet projects. In the period between 1923 and 1933, Carver traveled with the Commission on Interracial Cooperation to promote racial equality in the South, according to Biography. While Carver would give speeches about racial harmony to white Southern colleges, he largely refrained from criticizing any policies of the time or personally making any political statements.

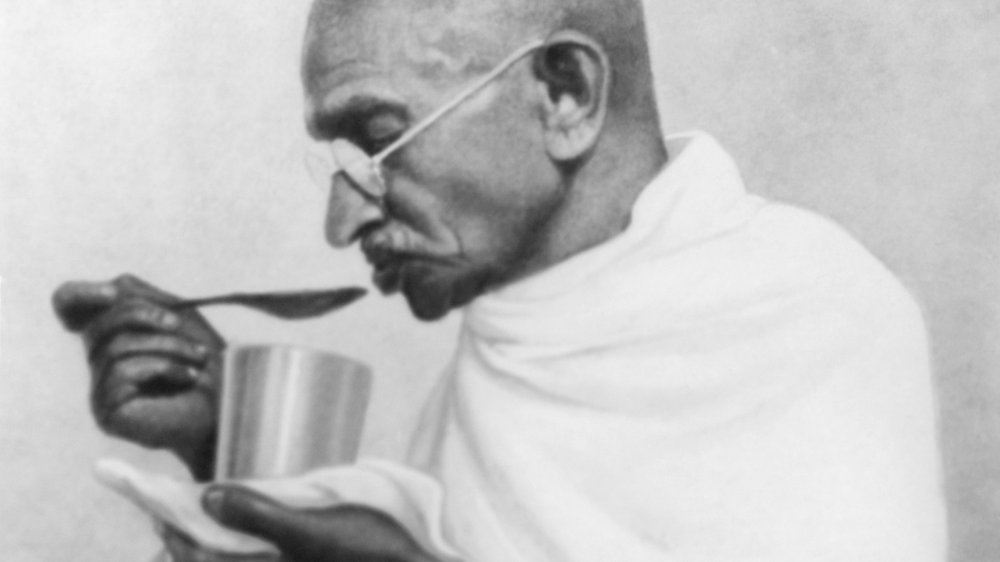

Funnily enough, Carver developed a friendship with Mahatma Gandhi in 1929. The Indian leader was a vegetarian and asked about how he could improve his nutrition. Carver gladly fielded his questions and recommended that Gandhi add some soy to his diet, per Biography. He trekked to India once and advised Gandhi on nutrition in developing nations. Even Joseph Stalin asked Carver to come revive the Soviet Union's cotton crop in the 1930s, but Carver refused.

Always looking to help, during the polio epidemic of the 1930s, George Washington Carver was an advocate of peanut oil massages and believed they could offer some relief for patients with paralysis, as told by History. It was called "Carver's cure." Reportedly, President Franklin D. Roosevelt tried out Carver's massage technique (though, it was never proven to work).

George Washington Carver's legacy

George Washington Carver's lasting legacy is a series of contradictions. While he invented products prolifically, Carver only took the time to patent three of his inventions, two stains and a cosmetic. While Carver was a devout Christian, he believed firmly in scientific inquiry. While George Washington Carver seldom spoke out against racial persecution, his life's work and level of achievement pushed boundaries forward for the Black community.

According to History, Carver died on January 5, 1943, after a fall down the stairs. Always frugal, he was able to leave behind a life savings of $60,000 to found the George Washington Carver Institute for Agriculture at Tuskegee, per Live Science. After his death, President Franklin D. Roosevelt erected a national monument to Carver in his hometown of Diamond, Missouri — the first-ever national monument dedicated to celebrating a Black American.

Black contemporaries looked to Carver as an example that education was a transformative path to success, while white people of the era saw Carver as proof that Blacks could be successful while still living in a segregated Jim Crow-era America, NPR explains. Throughout his life, George Washington Carver's top concern was uplifting the economic lives of Black people and rural farmers in the United States. As Carver once put it: "No individual has any right to come into the world and go out of it without leaving behind him distinct and legitimate reasons for having passed through it."