The Crazy Real-Life Story Of W.E.B. Du Bois

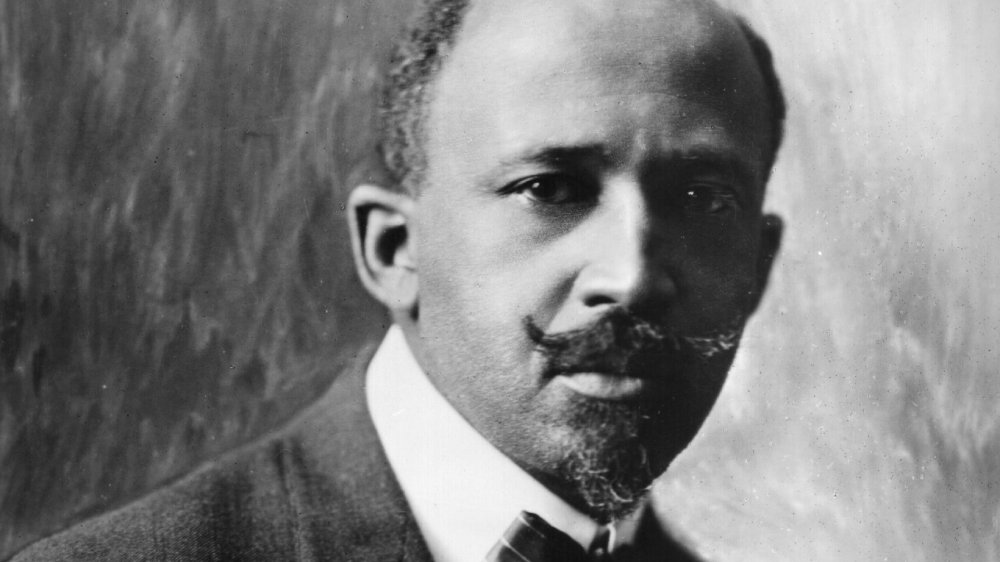

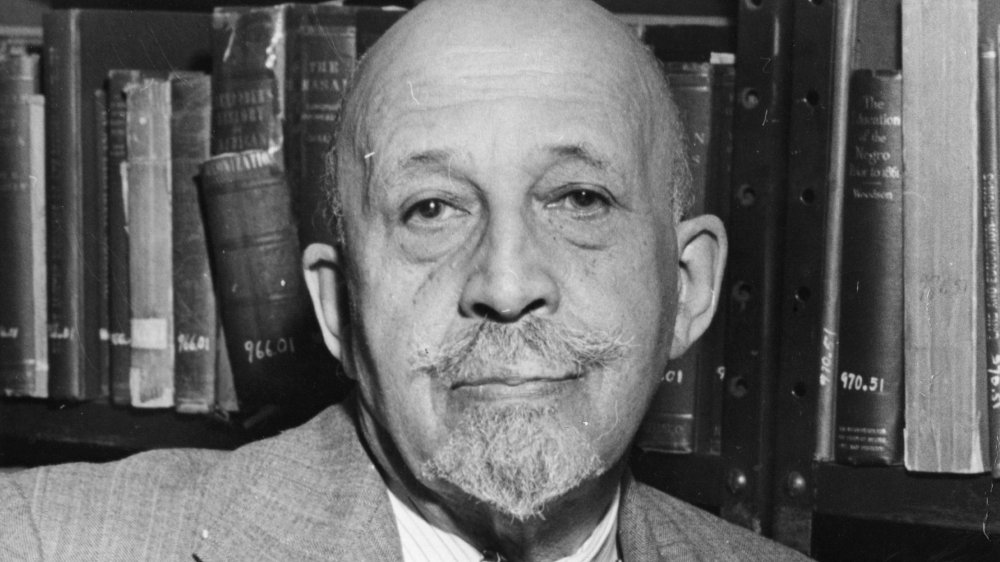

When you chronicle the many courageous Black American heroes who have fought against the racism embedded in the United States — from Frederick Douglass to Malcolm X, Martin Luther King to Angela Davis — no list of names is complete without W.E.B. Du Bois. Born in the wake of the Civil War, a co-founder of the NAACP, a leader of the Niagara Movement, and author of the acclaimed The Souls of Black Folk, Du Bois was a champion of promoting the use of hard data to address serious social issues. His progressive views, knowledge, and advocacy were decades ahead of his time, and there's no doubt that he'd have a lot to say about the systemic racism, mass incarceration, and police brutality still facing the United States today.

Like so many of Du Bois' peers, though, the struggles he faced in his own life were often devastating. From oppression due to the color of his skin, to an attempted silencing during the era of McCarthyism, Du Bois lived a fascinating, but often painful, existence, and throughout it all, he never stopped fighting for a better, more equitable tomorrow.

W.E.B. Du Bois lived from the end of the Civil War to the dawn of the Civil Rights movement

Few people in history have experienced a life as long, accomplished, or unique as William Edward Burghardt Du Bois. Born in 1868, a mere three years after the end of the Civil War, Du Bois spent nearly a hundred years on Earth, living until 1963. Thus, Du Bois essentially lived from the Civil War until the Civil Rights movement — a time that included two World Wars, a Depression, and Jim Crow — and Du Bois spent the bulk of these decades championing social justice, civil rights, and the end of colonial power.

However, while Du Bois' path would lead him to become a huge figure in the fight against racism, it took a few years before he experienced these struggles firsthand. Du Bois' hometown was Great Barrington, Massachusetts, according to Biography. He would often describe his childhood as a happy one, and while his town and school were predominantly white, he said that his teachers positively embraced his studies. The first time that Du Bois claims he recognized the realities of racism, firsthand, was in one of these classes, according to Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, when a classmate rejected the opportunity to exchange greeting cards, purely because Du Bois was Black. This was a touchstone moment for Du Bois, who later wrote that he suddenly realized the "two-ness" of being Black in America.

Du Bois' first encounter with Jim Crow laws came in college

Due to the admiration that Du Bois gathered in his Massachusetts hometown — and as the first person in his family to attend high school — the local churches banded together to pay his tuition for college, according to History. Du Bois was admitted into Fisk University, in Tennessee, where he also became the editor of a student magazine, The Herald.

However, it would have been on the very train ride that took him to the South that he first became fully acquainted with the toxicity of Jim Crow. As explained in the book American Thinkers: W.E.B. Du Bois, the young student from the North would have found himself on a segregated train, riding a Jim Crow car — cars which, in general, were substandard, poorly maintained, and overcrowded, compared to the white train cars. Tennessee had been the first state to enact post-Civil War laws that separated Black and white communities in public spaces, and white supremacy was growing worse, not better, as lynching became increasingly prevalent. As Du Bois wrote in his autobiography, "Murder, killing, and maiming Negroes, raping Negro women — in the 80s and in the southern South, this was not even news; it got no publicity, it caused no arrest; and punishment for such transgression was so unusual that the fact was telegraphed North."

These experiences with the hideousness of white supremacy would prove formative for Du Bois, and deeply influence his future direction in life.

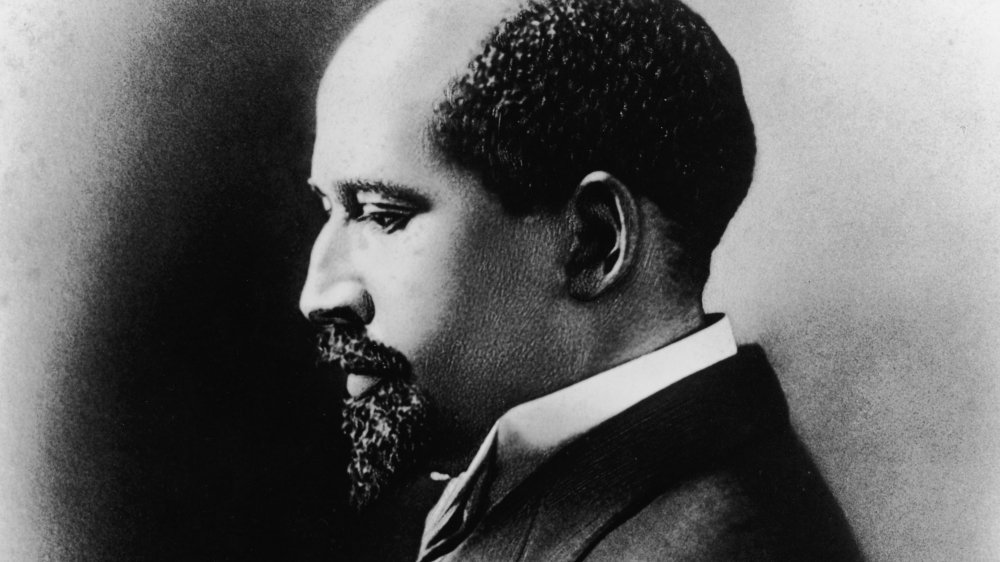

W.E.B. Du Bois soon became a world-class scholar

The insight, intelligence, and perceptiveness of W.E.B. Du Bois, particularly in his time, is nothing short of astounding. As History reports, Du Bois' work as a sociologist and activist transformed the way that Black life and Black struggles were seen in the United States. He was an early proponent for using data and statistical analysis to address sociological problems, confronting white supremacy head-on, asking bold questions, and drawing awareness to the poverty facing the Black community. On a broader scale, Du Bois came to believe that racism was a symptom of the capitalist system itself.

Du Bois was the first Black American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard, and following this success, he continued his studies in Germany, according to Biography. It was here that he would study and adopt the leftist perspectives that influenced all of his future work. By 1899, he had produced The Philadelphia Negro: A Social Study, a landmark case study on the Black communities of the United States. By challenging racism with hard data, as Mona Chalabi wrote for the Guardian, Du Bois demonstrated that scholarship and activism could be one and the same, as seen when he presented his data at 1900 World Exposition in Paris for the world to see.

Du Bois, of course, was also a distinguished author, with his most celebrated work being his 1903 publication, The Souls of Black Folks, a collection of 14 essays.

The conflict between W.E.B Du Bois and Booker T. Washington

At the dawn of the twentieth century, W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington had extremely different ideologies regarding the path to equality — and the echoes of their debates have continued reverberating into the present day.

Washington, for his part, had the "conservative" argument, as explained by Biography, as he believed that the Black community should put aside protests, civil rights debates, and political agitation — basically, putting aside the fight for equality — to instead work hard, follow the rules, and in the future, presumably "earn" equal rights as a reward for winning white people's respect. This stance, pejoratively called the "Atlanta Compromise," was anathema to the more "radical" W.E.B. Du Bois, who argued that this approach merely perpetuated white supremacy, and that the only way for the Black community to achieve social and political equality was to fight for it through protests, political battles, and agitation. Washington's conservative argument, of course, was largely proved false by white people themselves, as Ta-Nehisi Coates writes for the Atlantic, since Washington had assumed that separation would breed safety ... when, in reality, white mobs continued to violently and senselessly attack Black communities in horrific fashion.

In the end, history has shown that true change occurs not through compromise, but through protests, mass movements, and public demonstrations, of the sort Du Bois endorsed, which forcibly shift the Overton window, and force prejudiced power structures to buckle under the weight of public opinion.

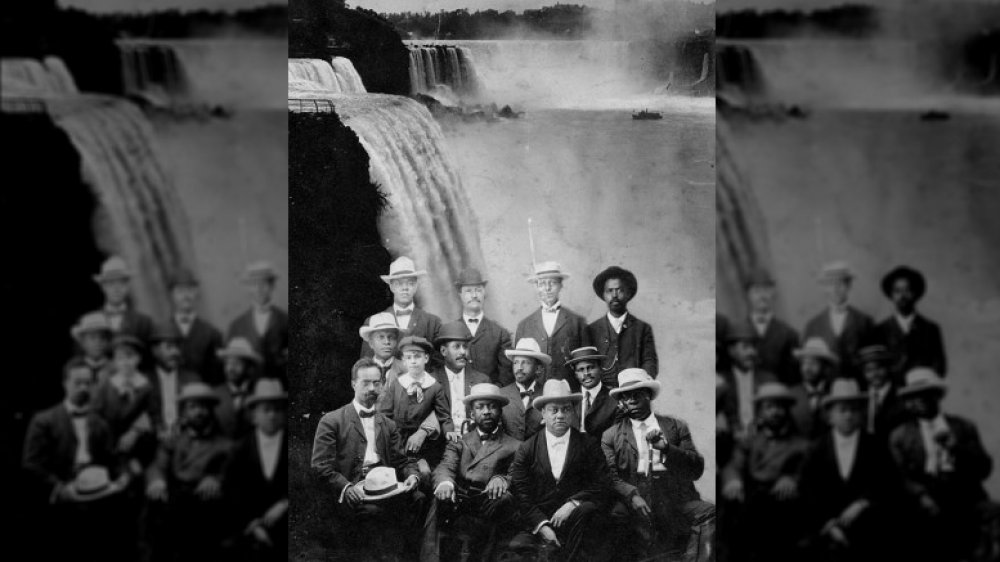

W.E.B. Du Bois co-founded the NAACP

W.E.B. Du Bois didn't want the modest reforms advocated by Booker T. Washington's infamous "Atlanta Compromise" with white Southerners. He wanted Black Americans to have full equality, as promised by the Fourteenth Amendment, and he believed that radical action — a fight for liberation, not subordination and/or accommodation — was necessary. That's why, in the midst of escalating Jim Crow laws and lynching, Du Bois and a number of other individuals met in Niagara Falls in 1905, according to the National Endowment for the Humanities, and formed what was referred to as the "Niagara Movement," which called for full suffrage, complete freedom of speech and press, the end of discrimination based on race, and other demands that terrified the white elite.

Four years later, in 1909, the same group behind the Niagara Movement took things to the next level, and founded the National Organization for the Advancement of Colored People, or the NAACP, an organization that fought to end Jim Crow, to give Black students fair opportunities in education, and to advance anti-racist causes. Co-founder Du Bois served as the NAACP's Director of Publicity and Research, while also working as the editor of their magazine, The Crisis, where he worked to highlight true stories of violent racism that were ignored by mainstream publications.

Other founders included Ida B. Wells, Mary White Ovington, Oswald Garrison Villard, and Mary Church Terrell, according to the NAACP's website.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Riots were a defining moment for W.E.B. Du Bois

In 1906, as explained by Georgia Humanities, armed mobs of white people descended on the streets of Atlanta, Georgia, and proceeded to murder and/or brutalize the Black population. Somewhere in the range of 25 to 40 Black Americans were killed by white supremacists, who destroyed Black property, ripped people right off street cars, and terrorized the streets for two days.

W.E.B. Du Bois bore witness to this carnage — securing himself and his wife in their apartment during the riots, and even buying a gun to protect his family from white supremacists — and this terrifying incident proved to be a pivotal moment in his trajectory. Du Bois penned the poem "The Litany of Atlanta," in response to the violence, and it convinced him of the necessity of an organization dedicated to promoting social justice, directly leading to his role in co-founding the NAACP. On a broader public level, as Mental Floss notes, the Atlanta race riots effectively proved the weight of Du Bois' arguments in contrast to the "accommodation" philosophies of Booker T. Washington: Clearly, white supremacy wouldn't step aside willingly, and ending the carnage required more aggressive political agitation and protest, in order to achieve equal rights and equity for the Black community.

W.E.B. Du Bois' Senate run

When looking at the broad scope of W.E.B.'s long and accomplished life, it's important to note that, even in his later years, he never stopped fighting for justice and equality — no matter how steep the odds.

For example, in 1950, at the age of 82, Du Bois — instead of retiring — ran for public office. He entered the election for U.S. Senator of New York, according to Gerald Horne's W.E.B. Du Bois: A Biography, running on the American Labor Party ticket, on a progressive platform of anti-nuclear, pro-labor views. This would've been a grueling campaign for a younger man, to say nothing of one in his eighties, as it placed him against the powerful and entrenched incumbent Senator Herbert Lehman. Du Bois was fiercely attacked for his run — Du Bois was a leftist with socialist views, running against a moderate liberal, a conflict which has echoed through so many U.S. elections ever since — and he knew from the start that his chances of winning were slim, particularly as a third party candidate, but he ran primarily to argue on behalf of civil rights and world peace, at one point even drawing a crowd of 1,500 in Harlem. In the end, according to AJC, Du Bois pulled in over 200,000 votes, about 4 percent of the total, and he continued fighting for progressive causes by proposing a left-wing coalition to challenge other political seats in New York.

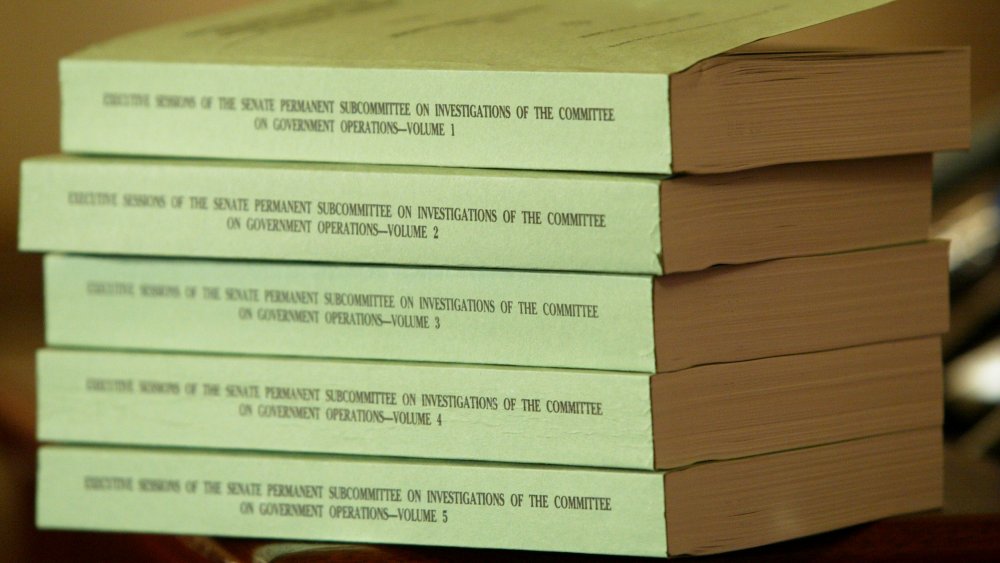

As a leftist, W.E.B. Du Bois was hit hard by McCarthyism

Propaganda is a dangerous thing, particularly when used by white supremacy for the purpose of weaponizing social justice leaders against social justice movements. Malcolm X, for instance, was never the violent figure that white propaganda painted him as, but rather, a thoughtful and powerful leader. Similarly, the sanitized version of Martin Luther King, Jr. often taught in schoolbooks today is not the real-life radical who stirred up a revolution in the sixties, publicly decried the Vietnam war, and argued for a universal base income. So, to understand the true W.E.B. Du Bois, it's important to also understand that his core philosophy not only denounced the evils of racism, but also the evils of capitalism, which he saw as inextricably linked. As detailed by the African American Review, Du Bois was an unapologetic socialist, a supporter of women's rights, and an anti-nuclear protester.

Sadly, this unabashed progressiveness caused him to smash, hard, into the gates of McCarthyism, wherein anyone with leftist views risked accusations of being a spy for the Soviet Union. The FBI monitored Du Bois, and in 1951, the 83-year-old scholar was taken away in handcuffs, according to the Boston Review, and branded as "Un-American." Such trials were primarily conducted to silence leftists, but Du Bois' arrest triggered massive media attention, as well as a star character witness in Du Bois' friend, Albert Einstein, so Du Bois was quietly acquitted due to lack of evidence.

W.E.B. Du Bois faced severe financial struggles late in life

W.E.B. Du Bois survived his brush with McCarthyism, and was acquitted, but his reputation still was smeared in the dirt. Despite his prized intelligence, his accolades within intellectual circles, and the many achievements and movements he had spearheaded over the decades, the public accusations of Du Bois being an agent for the Soviet Union — while false — were used to slander him, sapping away at his power to fight publicly against nuclear weapons, racism, and other causes he believed in. According to the Boston Review, the U.S. government's attack on Du Bois left him blacklisted. For three years in the fifties, his passport was revoked. The publicity of the trial pummeled his career so badly that he could barely afford groceries and utilities.

On a personal level, according to AJC, the whole ordeal left Du Bois deeply hurt, particularly since, after everything he had done and fought for, his allies in the NAACP never stood up to defend him when he was put up on trial.

The father of modern Pan-Africanism

W.E.B. Du Bois was a civil rights activist on a global scale, trying to improve the lives of marginalized people across the world. Du Bois has been pronounced by both New African Magazine and Encyclopedia Britannica as the "father of modern Pan-Africanism" — the cultural movement which unites the African diaspora under the believe that all people of African descent are united in cause, history, and future — and throughout his life, Du Bois was quick to point out that racism was not a problem isolated to the United States, as seen by the struggles of Black Africans living under European Colonial rule.

In 1900, Du Bois gave the closing address for the Pan-African Conference in London, and in 1919, he organized the first Pan-African Congress, calling for an end to the ways of European colonialism. African leaders such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, and Hastings Banda of Malawi would all later cite Du Bois as a major influence.

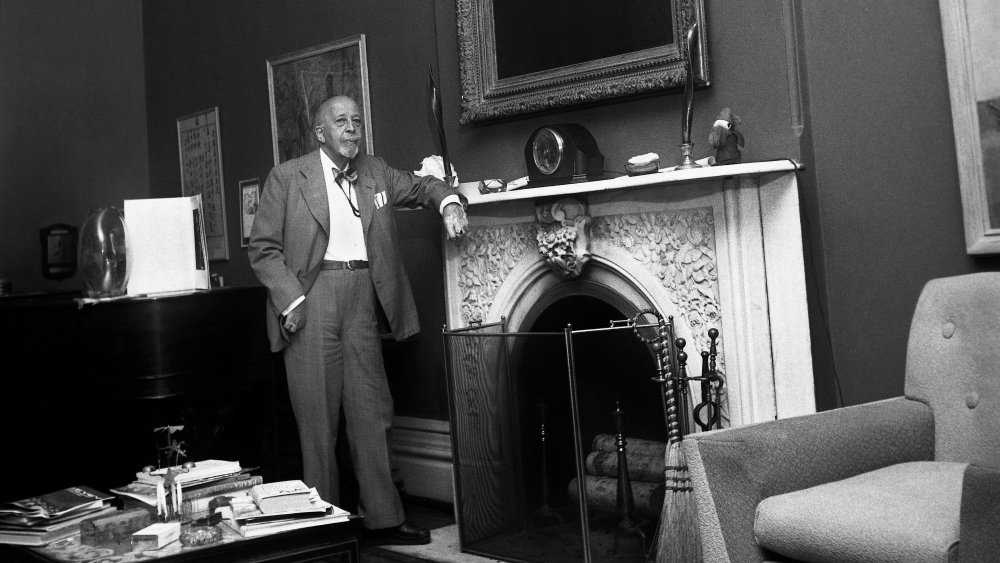

W.E.B. Du Bois, citizen of Ghana

After the prejudice, betrayals, monetary struggles, and blacklisting that W.E.B. Du Bois faced in the United States — particularly following his run-in with McCarthyism in the fifties — he eventually found a new home in Ghana, according to New African Magazine, where he was personally invited by the nation's first president, Kwame Nkrumah. Du Bois' had been one of the president's biggest inspirations, and Nkrumah had led Ghana to break from colonial rule in 1947, according to the Daily Beast, making it the first African country to achieve independence from Europe.

Ghana would, in the end, prove to be the place where Du Bois lived out his last years on Earth, after renouncing his U.S. citizenship, as the climax of a life spanning nearly a century. Ghana was his final home, his burial site, and the subject of his poem, "Ghana," which he dedicated to Nkrumah, containing the lines: "Here at last, I looked back on my Dream; I heard the Voice that loosed The Long-looked dungeons of my soul I sensed that Africa had come Not up from Hell, but from the sum of Heaven's glory."

The death and legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois

The philosophies and activism of W.E.B. Du Bois proved to be some of the most enduring, profound, and impactful of the century. Throughout his life, he never backed down, whether he was faced by white supremacist mobs or the prejudice of the U.S. government. In 1949, according to the Boston Review, he summarized his beliefs in one unforgettable statement: "Peace is not an end. It is the gateway to real civilization."

Sadly, in a bizarre historical coincidence, Du Bois expelled his final breaths of air, in Ghana, merely one day before the historic March on Washington, wherein Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave the rousing speech that would one day be his immortal legacy. Du Bois had dreamed of a similar march, some 60 years prior, according to New African Magazine, and on that prior night, the elderly scholar had written King a personal letter. Some months before that, Du Bois had written another letter to the march's organizers, seeming to realize that his life was nearly at its end, and stating, "Always I have been uplifted by the thought that what I have done well will live long and justify my life."

Certainly, Du Bois' impact on the world cannot be understated. While the march for true equality continues today, as embodied by the Black Lives Matter movement and the protests against police brutality, mass incarceration, and systemic racism, Du Bois' powerful voice lives on, and continues to inspire others.