Here's How Hannibal Almost Conquered Rome

When the sun rose on August 3rd, 216 BCE, the future of the Roman Empire seemed in mortal peril. The day before, the Roman army had marched to meet Hannibal's invading force outside the of Cannae, only for 48,000 Romans and various allies to die at a rate of 500 deaths a minute, according to History Extra. This was Hannibal's third decisive victory and the Second Punic War seemed to be heading towards a its end point.

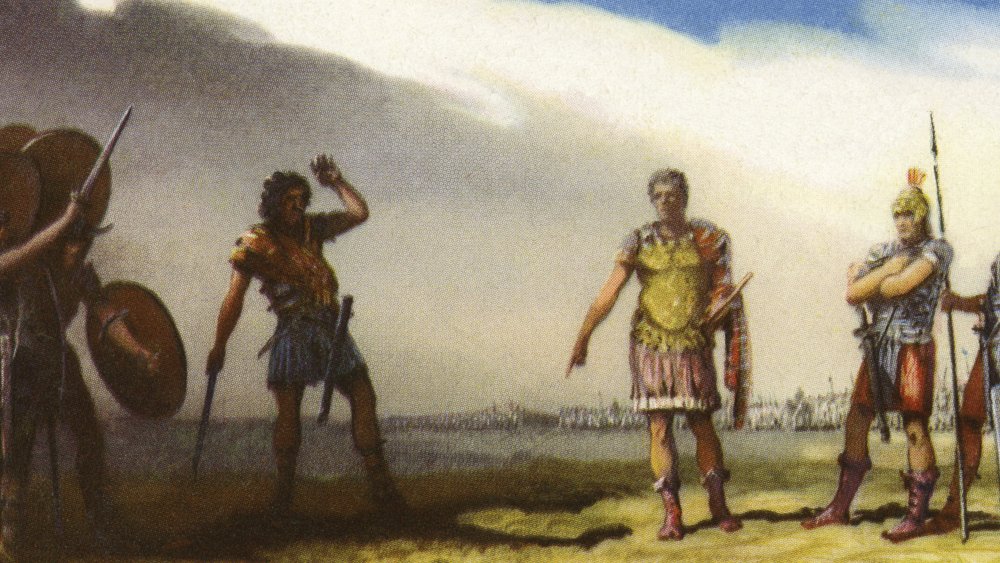

Hannibal had engaged the Romans with the daring move of invading Italy through the Alps, losing most of his men as he went. But while Hannibal was indeed a military genius, the defeat was also caused by Caius Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemilius Paullus, the two consuls leading the Roman army, as the Ancient History Encyclopedia explains. Every year, a new set of consuls were elected and the previous consul Quintus Fabius Maximus Verrucosus had been following a very unpopular strategy that consisted of attrition, not derring-do. So, the two new consuls moved to attack Hannibal. After all, they outnumbered him. The Romans attacked, the Carthaginian infantry "retreated," and Hannibal's cavalry swept around the rear, trapping the entire force inside. Wholesale slaughter ensued.

By this point, Hannibal's army had managed to slay about 175,000 Roman and Italian soldiers in under two years, according to Dickinson College Commentaries. The Macedonians, a kingdom based around today's Thessaloniki, agreed to attack Rome on a second front. Still, the Romans refused to capitulate to the Carthage.

Winning battles but losing wars

After the catastrophic defeat, the Romans quickly decided to adopt the previously maligned Fabian strategy. Hannibal's strategy, according to Fact Behind Fiction, focused on defeating and killing Roman soldiers to destroy the burgeoning empire while releasing Italians: "I have come not to make war on the Italians, but to aid the Italians against Rome." So, by denying Hannibal the battles he needed to win, the Romans deprived him of victory. Similarly, the other prong of their approach, a scorched earth tactic, kept Hannibal from laying siege to Roman cities.

However, the Fabian strategy only resulted in a stalemate. Hannibal won some battles, lost more troops, but still remained in Italy. So, in 204 BCE, a young, newly-elected consul Publius Cornelius Scipio invaded Carthage, a crisis that forced Hannibal to leave Italy. Hannibal's invasion had failed. The two armies engaged in the Battle of Zama in 202, according to Encyclopedia Britannica. Here, Scipio employed the cavalry trick from Cannae, and crushed the Carthaginian forces. Hannibal had lost. Rome was now the sole superpower.

However, even in defeat, Hannibal had conquered the imaginations of the Romans. In Virgil's Aeneid, composed almost 200 years after the war, Juno's love of Carthage is the cause of the Trojans' suffering. And to this day, the phrase "Hannibal is at the gates" is used to express fear and anxiety, especially in little Roman children who don't eat their supper. During the rest of Ancient Rome's days, no other foreigner ever managed such an impact.