The Real Reason People Still Read Sun Tzu's Art Of War

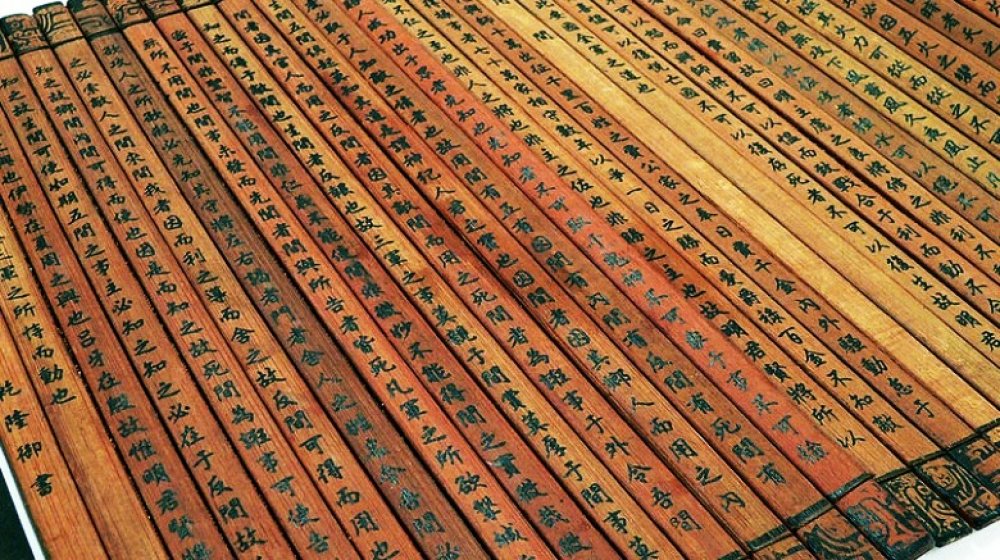

The Art of War was written some time in the 5th Century BCE by acclaimed (and possibly nonexistent) Chinese military strategist, Sun Tzu. This slim, thirteen-chapter volume provides practical advice on how to win a war. If you ever wondered how a military general goes about the deadly business of playing Risk with real lives, this little gem delivers a roiling mushroom cloud of unsettling insight.

Now, Art of War is obviously going to be right up a military historian's alley. That's a no-brainer. But how does a two-and-a-half thousand-year-old how-to manual — essentially a heavily outdated edition of Warfare for Dummies — manage to fetch over five million Google hits in the 2020s?

Today, The Art of War is read as a guide to business strategy. The vast majority of folks thumbing through Sun Tzu's glittering manifesto to military brinkmanship don't wear army boots. In fact, the closest that many of these contemporary readers will ever come to a physical confrontation is when a snooty hipster cuts in front of them at Starbucks. However, the book's elegant set of martial strategies possess one sharply crystalline idea at their core: "Know your enemy, and know yourself." According to Larry Kim, a C-suite executive writing for Inc Magazine, Sun Tzu's warlike philosophy can teach business people to "learn how to recognize opportunities to strike smartly and efficiently. There is much skill in business, but managing conflict and competition is an art as old as time."

Business is war

It is the perceived wisdom that business is war. The basic language building blocks of the board room are filled with war metaphors, as Harvard Business Review points out. From "captive markets," to "competitive advantage," to "hostile takeovers," the climate-controlled air in your garden-variety office is alight with an endless barrage of ass-kicking catchphrases. Even the word "strategy" comes from the ancient Greek word for a military general. And, of course, there's at least a teaspoon of truth in the idea that humans use such words because that's what humans are — creatures that use stupid-large brains to compete for limited resources.

With human evolution as a starting point, here's one way of answering the question of why people still dip into Sun Tzu's Whitman's Sampler of warmongering wisdom: Sun Tzu isn't just talking about war. He's speaking the basic language of what it means to be human. It doesn't matter if you're a social media influencer, sell novelty socks, or operate the happy end of a rocket-propelled grenade launcher.

Humans compete. Therefore, Sun Tzu's ideas are timeless.

Is that a good thing, though?

Basically, people get a buzz from thinking of their daily grind as a dramatic tale of overcoming adversity. Case in point: Trading Places — the iconic Eighties-era tale of battle-field business — wouldn't have been much of a story if everyone had just gotten along, selling orange juice to needy orphans with the occasional friendly spat over who's top of the Duke & Duke fantasy football league. And storylines help! They structure events. They reduce boredom. Maybe working life is just a grayer, less satisfying place without a Dwight Schrute figure playing evil nemesis to a prototypical Jim Halpert good-guy archetype. Is there any harm in that?

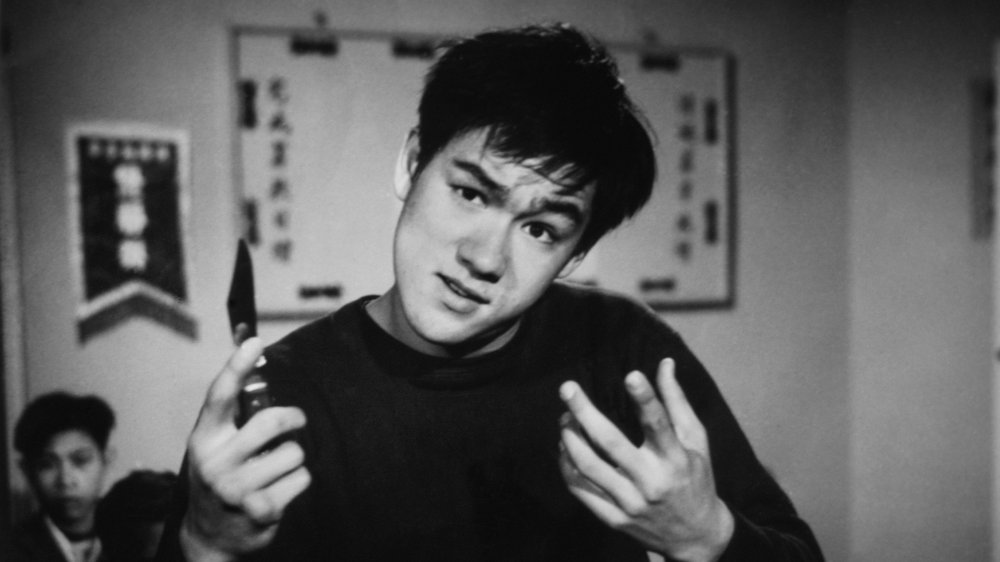

Possibly. The Harvard School of Negotiation argues that using warfare as a way of understanding business is a double-edged sword (irony of battle-field lingo very intentional). They claim that "metaphors both clarify our vision and distort it. [...] For example, seeing bargaining as warfare allows us to borrow strategies and tactics from the battlefield but may blind us to the fact that negotiation is also much like a dance." This is an interesting point. A 2,000-year-old treatise on how to Chuck Norris an enemy army into submission may still offer a useful metaphorical toolbox for ambitious executives eager to find success. However, it's probably worth pointing out that even Bruce Lee was one heck of a good dancer.