The Population Decline We're Not Ready For

On July 15, Lancet, the peer-reviewed medical journal, published the findings of a series of models they've implemented to predict the future of humanity's population based on trends in fertility, migration, and mortality rates. What they found was that the fertility rate in almost every country will drop below the replacement level — that is, the amount of newly-spawned children needed to keep a level population — by 2100. Because of this, every country's population will both age and drop, with the most extreme examples being twenty-three countries, including South Korea, Thailand, Spain, and Portugal, that will see their populations drop by more than half in the time between now and 2100. The example that the BBC gives is that Japan's population of 128 million will diminish to 53 million.

Despite the mildly apocalyptic titles with which news sites greeted this report, such as the BBC's "Fertility rate: 'Jaw-dropping' global crash in children being born," the data also shows that our societies have improved in terms of people not dying young so often, and ensuring more women have control over giving birth. So, in its own way, the drop in fertility, and aging societies, could be considered as signs of progress.

But, progress or not, the awaiting changes in population size will necessitate societal transformation.

Societies are growing older

The biggest issue, here, is that the decrease in population will result in what Professor Christopher Murray of the University of Washington's Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation describes as an "inverted age structure" — namely, the amount of old people will outnumber the young. Due to trends already mentioned, the number of under-fives will decrease from our current 681 million to 401 million in 2100, while those over 80-years-old will more than quadruple from 141 million to 866 million ... including every person alive right now!

One of the two obvious changes will be the shift of weight in population power: Nigeria, along with most of the other sub-Saharan countries, will explode in population, even with their projected declines. This means, as Dr. Murray also notes, that the need to address racist inequalities will be greater than ever: "Global recognition of the challenges around racism are going to be all the more critical if there are large numbers of people of African descent in many countries."

The other change, then, will be how people think about aging. As Harvard Business Review comments, there is already the cliche that "40 is the new 30," and so on. However, since that publication only really cares about the economy, their take on this is that people will develop new "career cycles," with differing expectations on how to move through the corporate ladder. Specifically, thinking about a world in which retirement may become unsustainable.

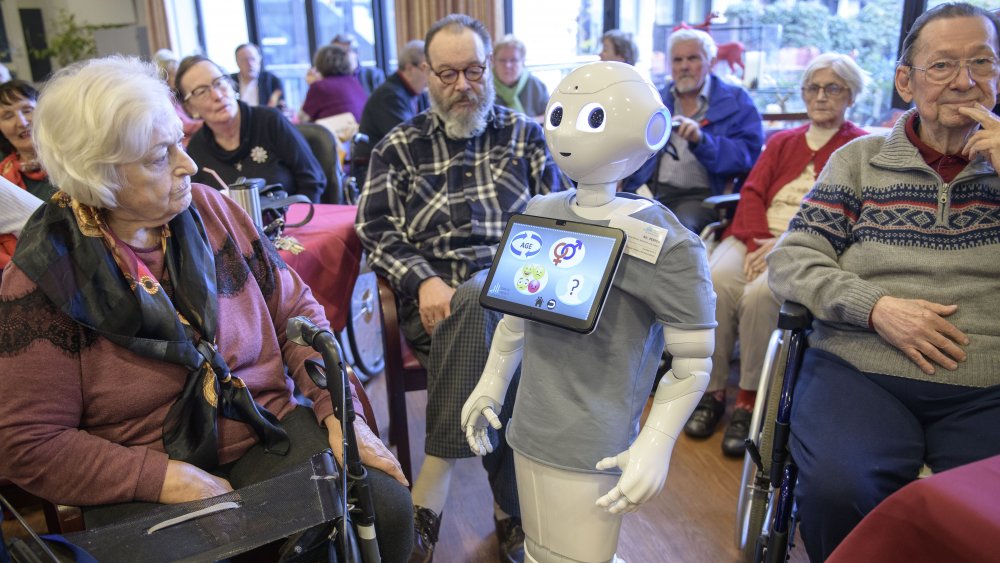

Aging into robots

If the economy is going to force people to work into old age, the powers-that-be will have to redesign the work environment to suit elderly bodies, or else lose out on efficiency.

The most likely solution seems to be that companies will develop robots to replace aging workers. The World Economic Forum illustrates this with an article examining construction workers in Japan, which already has become an aging society, with over 25% of its population over the age of 65. Shimizu Corporation, a construction contractor, has started developing three types of robots: a Robo-Carrier to transport supplies, a Robo-Welder to ... uh, weld, and a Robo-Buddy to install ceiling boards.

The amusing thing, though, is that conversations about robots and automation tend to summon images of layoffs and human obsolescence. However, the issue which the Japanese construction industry actually faces is that since they've only recently started to develop these robots, they can't actually replace the workers who have retired quickly enough. This issue has prompted both the Japanese government and Japanese businesses to invest heavily in the development of robotics and artificial intelligence, as Reuters reports. The Fourth Industrial Revolution may very well be caused not so much by groundbreaking advances in science, but a population aging into a different way of relating to the world.