Elliott Smith Was Never Cut Out For Fame. Here's Why

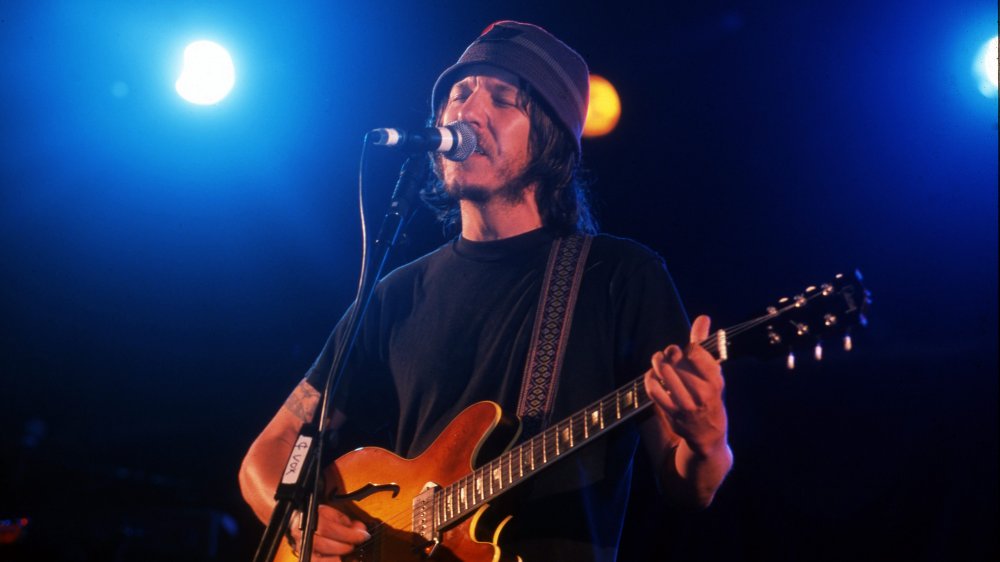

"Yeah, I don't know. I mean, I mostly only know things are different because people ask me different questions, but I don't feel like things are very changed... I'm the wrong kind of person to be really big and famous." Elliott Smith wandered through this answer in an interview with 2 Meter Sessions when asked about the changes he saw with Good Will Hunting. In the trope-shaped timeline of the romantic artist's demise, the reception of "Miss Misery," the Oscar nominated song which appeared on the soundtrack for Good Will Hunting, plays the pivotal point that directs him to his death.

Because the song was nominated for an Oscar, Smith got roped into playing it for the Oscars in 1998 by a threat that they would get a "Richard Marx" type to sing it if he refused. Looking back, however, he merely commented to Under the Radar that "[The night] was surreal enough that it didn't seem like it happened to me." And the further away he got from the night, the more abstractly he seemed to treat it: "I never think about the Oscar thing any more, except for the fact that it comes up in interviews. It doesn't bother me anymore." Still, he eventually moved to Los Angeles, the city where he would die in 2003 at the age of thirty-four after apparently completely abstaining from the drugs and alcohol that were ruining his life and performances. Regardless of what Smith may say, the arc follows the trope's formula.

Pushback against romanticism

Too often, however, these types of narratives are too contrived. That serves as the thesis Matthew LeMay puts forward in his contribution to Bloomsbury's 33 ⅓ series, which publishes individual books to examine in-depth an album. LeMay's looked at Elliott Smith's XO: "At a time when Smith was being groomed for a particular (and particularly condescending) brand of stardom, he produced a record that eviscerated one of the central assumptions of singersongwriterdom: that pain is beautiful. XO insists that romanticizing personal tragedy can only leave you 'deaf and dumb and done.'"

For those not interested enough to go for the book, Salon exhibits a section that characterized LeMay's general argument. The excerpt starts with a piece run by Yahoo in 1998 which describes Elliott as "seen by society as a f**k-up, he's a genius working in obscurity who's suddenly given the chance to enter the mainstream," just like Mr. Hunting. The problem is that it's sites like Yahoo that are decided that Elliot is a "f**ck-up" and, like Hunting, will be raised. In reality, although Smith wasn't a chart topper like Celine Dion, he had already released three albums and signed with a major label: "His extensive back catalog, its enthusiastic reception, and its modest commercial success often get entirely omitted... And—most troubling of all—Smith himself is positioned as a suicidal "f**k-up," whose "sudden" success as a musician is in no way the result of hard work, perseverance or–God forbid–ambition (I mean, the guy tried to kill himself!)."

The tragedy of Elliott Smith's passing

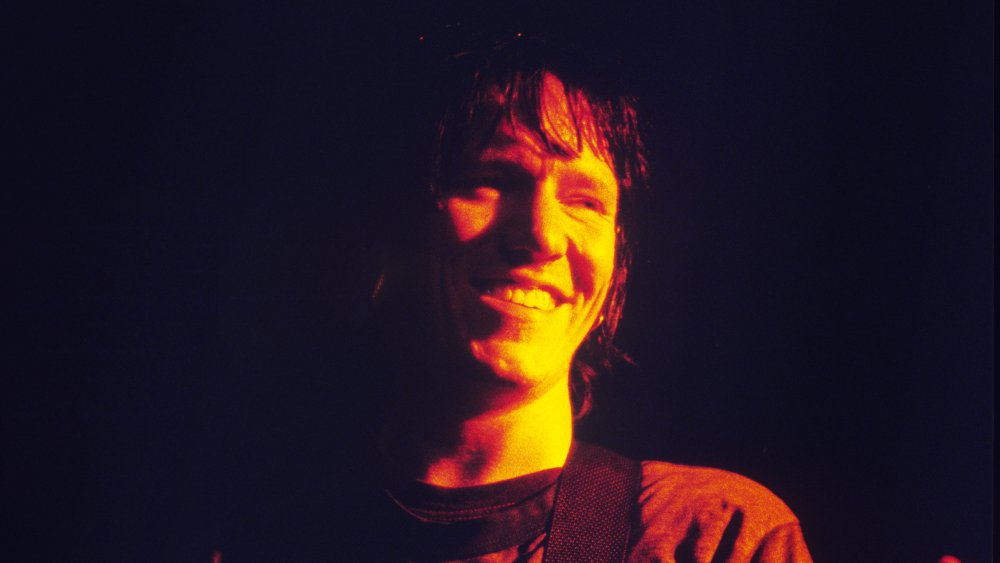

These rebuttals to the simplistic "fame got 'em" narratives in no way dismisses the tragedy of Elliott Smith's early passing. Like Kurt Cobain, Smith had problems that preceded the national spotlight — see his 1997 description of how he handled a breakup: "Um, yeah – I jumped off a cliff. But it didn't work." On the other hand, however, he would also tell NME [as quoted in The Independent] "I don't play music because I'm a tortured person. I play music because I enjoy it. I'm no sadder than anyone else I know. People overlook the happiness." He had severe emotional problems that he balanced for a while, but eventually couldn't.

Between going cold turkey on a series of dependencies, such as heroin, alcohol, and caffeine, and having, as Spin describes "memories of being sexually molested by his stepfather," Elliott Smith soon fell beyond the realm of being helped. If his 1997 move from Portland to New York to Los Angeles did set his death in motion, it was because he had severed himself from his community. Willamette Weekly describes how once he became famous "he lost the comfort of relative anonymity. He tried relocating to New York first, but found it didn't give him the isolation he desired. In L.A., he could disappear into the sprawl." He found quiet but he lost the safety net of "the people who kept him grounded back in Portland." Without them, Smith was a time bomb.