The Hidden Meaning Of The Clash's London Calling

While the word has metastasized into a cliche, "London Calling" by The Clash is a truly iconic song, so much so that it crashes into the 15th spot on Rolling Stones' list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time. Besides "Should I Stay or Should I Go," it is the Clash song. It appears in the James Bond film Die Another Day and in countdown coverage for the 2012 Olympics.

But, as Alan Connor quotes Marcus Gray in a piece for the BBC "London Calling is a classic example of a song that has become so familiar that its original meaning has been lost. It's instantly recognisable and superficially the perfect invitation to the capital and the world's premiere sporting event, but it's actually about the end of the world, at least as we know it."

Yes, the opening chords are almost instantly recognizable. Yes, it's got the word "London" in it. But surely, no matter how cool it is, it's not the best song to use for a London tagline, is it? That's the question Alan Connor asks in his article "Smashed Hits: Is London Calling the best anthem for a city?"

His main point begins with the song's title and recurring lyric: "London Calling." "London Calling" comes from the World War II introduction for BBC radio broadcasts to foreign countries: "This is London Calling. The news from Britain – up-to-the-minute, truthful." The Clash have war on their minds.

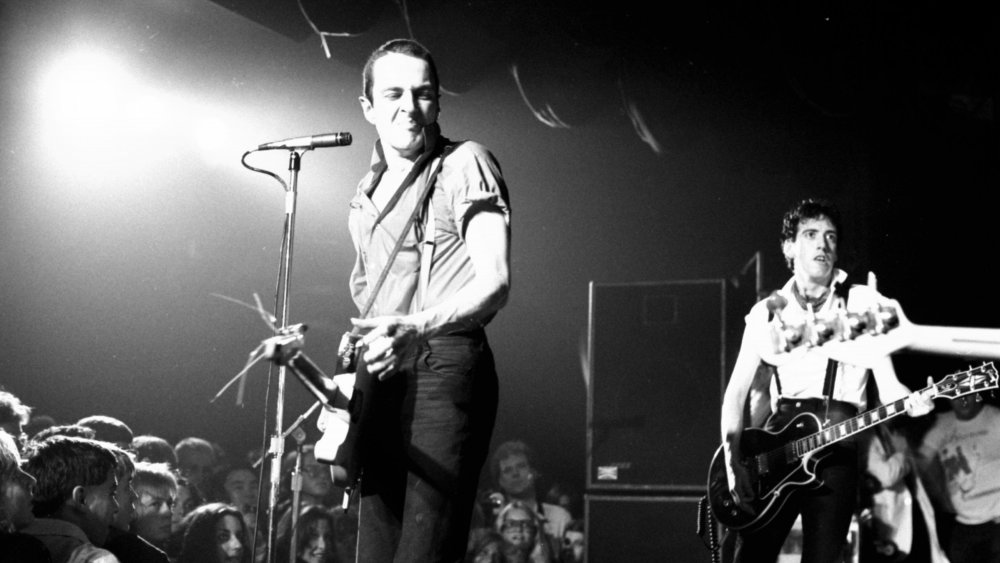

Phony Beatlemania

When you listen to what the words are directly stating, the apocalyptic doesn't so much creep as snarl throughout every verse and every chorus. When he explained to the Wall Street Journal the meaning of one of the most memorable lines — "Phony Beatlemania has bitten the dust" — Mick Jones rebuked the rationale behind using "London Calling" as the city's anthem: "The line about phony Beatlemania biting the dust was aimed at all the touristy sound-alike rock bands in London in the late '70s. We were fans of The Beatles, The Who and The Kinks—but we wanted to remake all of that... Our message was more urgent—that things were going to pieces." This follows directly from a command for the fans "don't look to us." The Three Mile Island nuclear reactor had melted down earlier that year, threats of the Thames overflowing and flooding London were rampant, and the newspapers were heralding plagues every day. The feeling of the scene was just as heavy with doomsday as today.

In the midst of the apocalypse, the song cackles in gallows humor. The chorus builds up, layering nuclear era upon sun drawing near upon wheat growing thin until Joe Strummer breaks it off to say he doesn't fear any of that. Why? Because London is drowning and he lives by the river, making him the first to go. The song is directed to the boys, girls, and zombies all around, telling them to wake up to the catastrophes occurring all around them.

Which London is Joe Strummer calling?

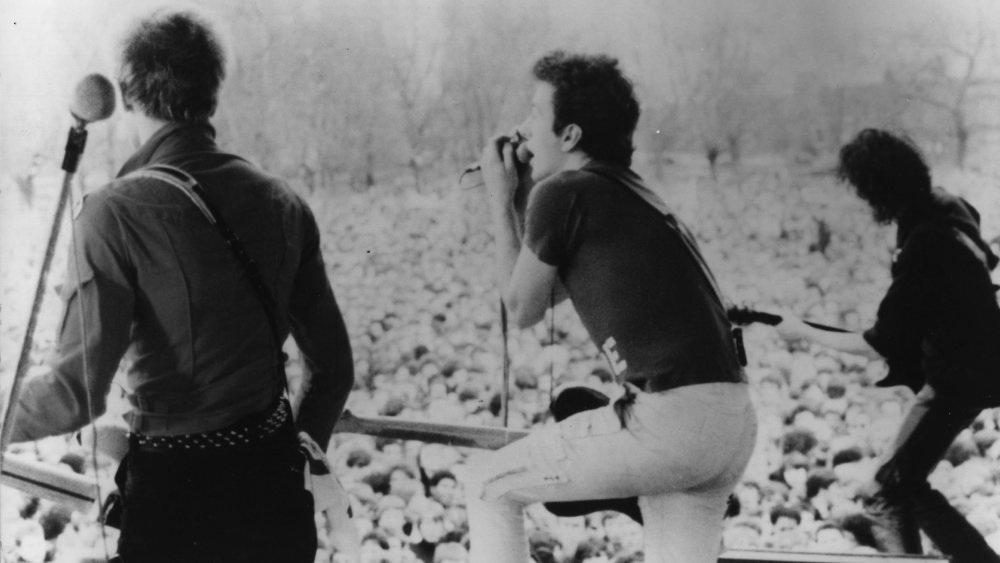

A few days after Alan Connor's article was published, Scott Simon, host of Weekend Edition, sat with him to talk about the disconnect. The song "London Calling," like many of the other songs by The Clash, revel in a left-wing political perspective. "[The song's] celebrating London," Connor explains, "but it's also repudiating the previous decade's idea of London. When he says, 'We ain't got no swing,' I think Joe Strummer is trying to put in the bin the red-bus, black-taxi, groovy-baby kind of London." More than that, however, is that the only swing left in London is the ring of a truncheon.

The sixties and all the touristic Disneyfication of London had to be ripped away so that the people the song addresses, whom the song shouts at for nodding out, can stand up for themselves. It's an excellent song and it rightfully earns its place as an iconic punk song, but using a song that rails against the papering over the troubles of the world as an ad for a fake London is not in the spirit of "London Calling."