The Crazy True Story Of Nellie Bly

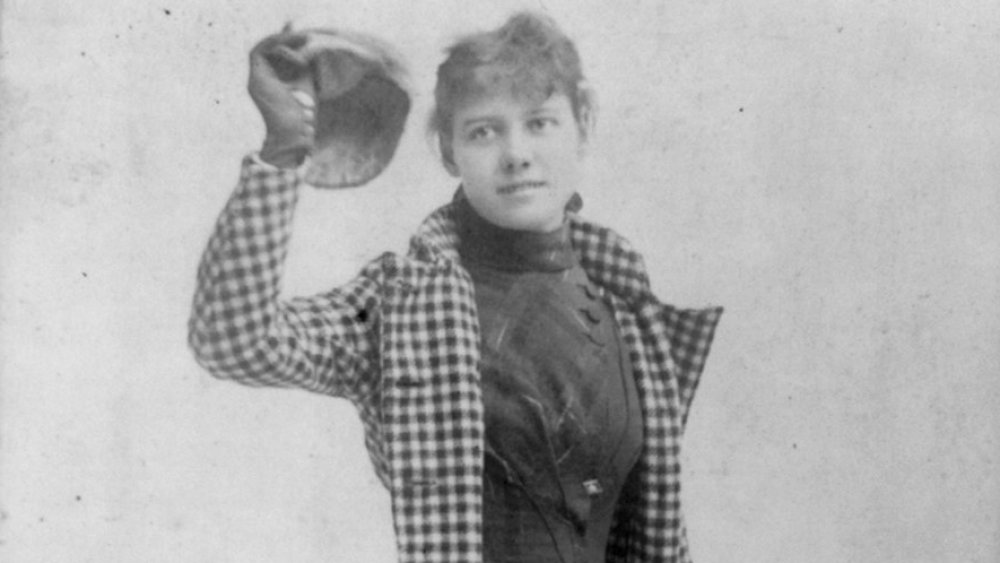

Nellie Bly was a pioneering investigative journalist during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Born in 1864, Bly was not only one of the first women to demand an equal role in reporting, but she was also one of the first journalists to embrace a hands-on, undercover approach to reporting that became the precursor to modern investigative journalism. From the dismal conditions faced by Pittsburgh's female factory workers to the harsh treatment suffered by asylum inmates in New York City, Bly was known for going undercover and reporting eye-opening exposés with clear, unflinching prose and a sharp wit.

Following the completion of her trip around the world in 1890, Bly became one of the most famous journalists in the United States. Nellie Bly died in New York City at just 57 years old, but her legacy as a reporter, as an activist, and as a reformer can still be felt today.

Nellie Bly was one of 15 children

For the first 20 or so years of her life, Nellie Bly was known not as Nellie, nor as Elizabeth Jane Cochran, which was her birth name, but as "Pink," due to her fondness for the color, according to New World Encyclopedia. It was one of the few things that helped set her apart from her 14 siblings. Her father, Michael Cochran, was a wealthy judge, mill owner, and landowner. Bly was born in Cochran's Mills, Pennsylvania, a town named in her father's honor, on May 5, 1864. By then, Michael Cochran already had ten children by his first wife, Catherine Murphy. She died in 1857, and he met and married Bly's mother, the widow Mary Jane Cummings, the following year, per Correction History.

The couple had another five children together, including Bly, and the large family lived relatively comfortably until 1870. When Bly was only six, Cochran died. He had no will, so Mary Jane had no legal claim to his estate. Instead, the remains of his estate were divided up between all of his children. Despite his wealth, the money did not go far when it was divided up between 15 people, and there was little left for Bly and her mother to live on after Cochran's death, according to ThoughtCo.

Bly's family moved to Pittsburgh for financial opportunities

With not much money and few other options, Bly's mother married a man named John Jackson Ford not long after Cochran's death. But Ford was frequently abusive and violent, and the next few years of Bly's childhood were marked with difficulty, fear, and financial uncertainty. But the marriage wouldn't last. Mary Jane divorced Ford in June 1879, according to ThoughtCo.

It was also around this time that Bly changed her name for the first time, adding an "e" to the end of Cochran because she believed it made her sound more sophisticated. The young Elizabeth Cochrane enrolled in the Indiana Normal School, a small teaching college in Indiana, Pennsylvania, in 1879. However, she couldn't afford the tuition, and she left the school in her first semester due to lack of funds.

According to American National Biography, Bly convinced her mother to move from her home in Apollo, Pennsylvania, to the nearby city of Pittsburgh, where two of her brothers had already settled. Bly believed there would be more opportunities to find work in the city but was disappointed to find that only a small number of jobs were open to women. Bly and her mother opened up a boarding house, and to help make ends meet, Bly worked at the few odd jobs that employed women, like housekeeping or serving as a wealthy woman's companion.

What Girls Are Good For

Despite her lack of formal education, Bly was smart, determined, and set on becoming a writer. Although she was unable at first to find paid writing jobs in Pittsburgh because of her gender, that didn't stop her from penning a fiery response to an article that was published in the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1880. Entitled "What Girls Are Good For," the piece's author, Erasmus Wilson, argued that women's participation in the workforce was "a monstrosity" and called instead for women to remain in the domestic realm, according to Biography.

Furious, Bly sent a rebuttal to the editor, arguing instead for an expansion of the "women's sphere," especially for women who bore the responsibility of financially supporting themselves and their families, according to American National Biography. She signed off as "Lonely Orphan Girl." George Madden, the Dispatch's managing editor, was intrigued by the response and placed an add in the paper asking for the "Lonely Orphan Girl" to come forward. Madden had been so impressed with her writing that when Bly identified herself as the author of the piece, he offered her a job at the Pittsburgh Dispatch as a full-time columnist. Bly accepted and immediately began another piece, entitled "The Girl Puzzle," about the effect divorce had on women.

At the time, most women journalists wrote under a pseudonym, and taking inspiration from a popular song by Stephen Foster called "Nelly Bly," she intended for that to be her pen name. However, her editor misspelled it as "Nellie," and the name stuck.

The Pittsburgh Dispatch

Nellie Bly began her journalistic career covering the dismal conditions faced by working women in Pittsburgh's factories. She began by reporting on the daily lives of women laborers in the city, investigating the dangerous factories in which they worked long hours in unsafe conditions for low wages. However, her reporting didn't earn her any popularity with the factory owners, and they soon barred her from entering their factories, according to History. Undeterred, Bly, for the first — but certainly not the last — time, went undercover as a factory worker and kept writing. She continued to expose the long hours, unsanitary conditions, and exploitation that working girls had to endure.

Tired of the bad publicity and public outrage Bly was stirring up, the factory owners complained to her editors at the Dispatch. They threatened to pull their advertising dollars from the paper if the editors didn't stop Bly's reporting on the conditions at their factories, according to Your Dictionary. The editors gave in to the factory owners' demands, and despite her proven investigative chops, Bly was soon relegated to the women's pages of the Pittsburgh Dispatch. Because of her gender, she was assigned to write "puff" pieces about beauty, fashion, and homemaking, rather than hard news stories about real women's issues.

Six months in Mexico

By 1886, Nellie Bly had grown tired of the women's pages. At just 21 years old, Bly got her chance to move beyond the traditional role of female journalists. She managed to convince her editors at the Dispatch to send her to Mexico and assign her the position of foreign correspondent, according to History. Her editors believed the assignment was too dangerous for a woman, so Bly brought her mother along. However, her mother didn't stay abroad long, and Bly spent the next five months in Mexico alone, reporting on Mexican culture and daily life.

But Bly wasn't any more content writing human interest stories in Mexico than she had been in Pittsburgh. Instead, she focused on the suffering endured by Mexico's working poor, reporting extensively on the poverty she saw there. Poor people living in Mexico City were "worse off by thousands of times than were the slaves of the United States," Bly reported.

Bly also wrote about Mexico's political corruption and was openly critical of the country's dictatorial government. After learning of a local journalist who was imprisoned for criticizing the Mexican government, Bly was outraged. She vocally criticized the arrest. When the authorities learned of Bly's reporting on the event, they threatened to arrest her as well. She was forced to flee the country and return to Pittsburgh, but she continued to criticize Mexico's corruption and blatant restriction of free press. Bly's pieces on Mexico were published as a collection, titled Six Months in Mexico, in 1888, per ThoughtCo.

'I'm off for New York. Look out for me.'

After returning from Mexico, Bly felt even more stifled writing for the Pittsburgh Dispatch. Still largely consigned to women's interest stories, Bly's ambition was to write articles that appealed to an audience of both men and women. She decided that the only place where she could write more serious pieces was New York City. In the spring of 1887, she left Pittsburgh with little warning, leaving a note on her editor's desk that simply read: "Dear Q.O., I'm off for New York. Look out for me. BLY," via American National Biography.

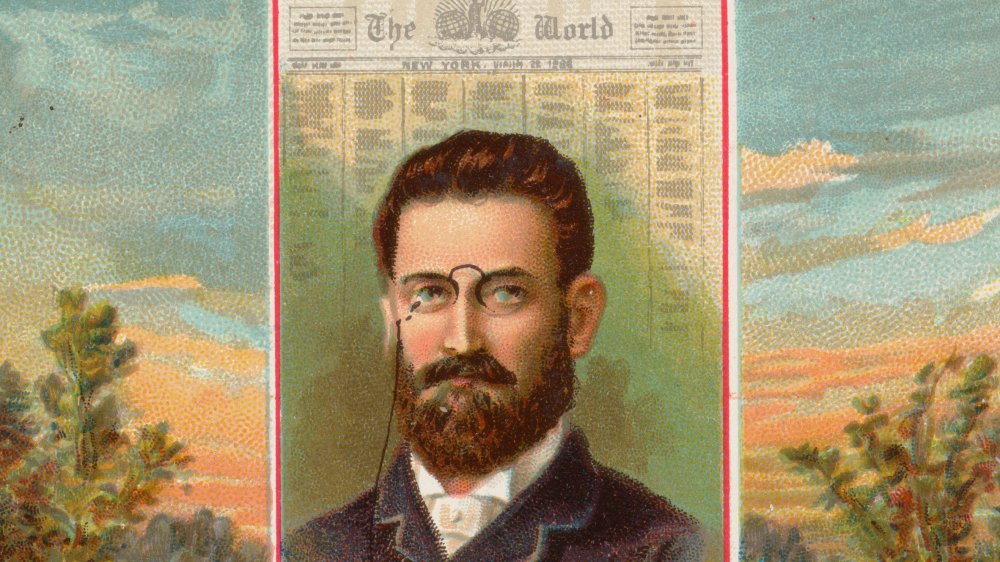

However, despite her ambition and talent, Bly still initially struggled find work. For the first four months, she was only barely able to supported herself by freelancing for the Dispatch from New York. But in September 1887, her move finally paid off when she met Joseph Pulitzer (pictured above). The owner of the New York World, Pulitzer was pioneering a new type of investigative journalism. He liked sensationalist and dramatic stories and soon became known for employing "stunt girls," whose pieces were attention-grabbing gimmicks to sell papers. However, he was also one of the few publishers who employed young women, giving them the chance to show their reporting prowess.

Pulitzer agreed to give Bly a trial assignment for the New York World, and her first piece was sure to be an attention-grabber. Per Your Dictionary, Bly, together with New York World managing editor John Cockerill, came up with the idea for Bly to go undercover in a madhouse.

Nellie Bly gets committed

Nellie Bly had a three-step plan for going undercover in the asylum. First, she had to be committed. She accomplished this merely by practicing looking and behaving in a "crazy" manner and then checking into a boardinghouse. Once there, she acted erratically, calling other boarders crazy and refusing to go to bed. The police were called, and Bly was taken to the courthouse, per New World Encyclopedia.

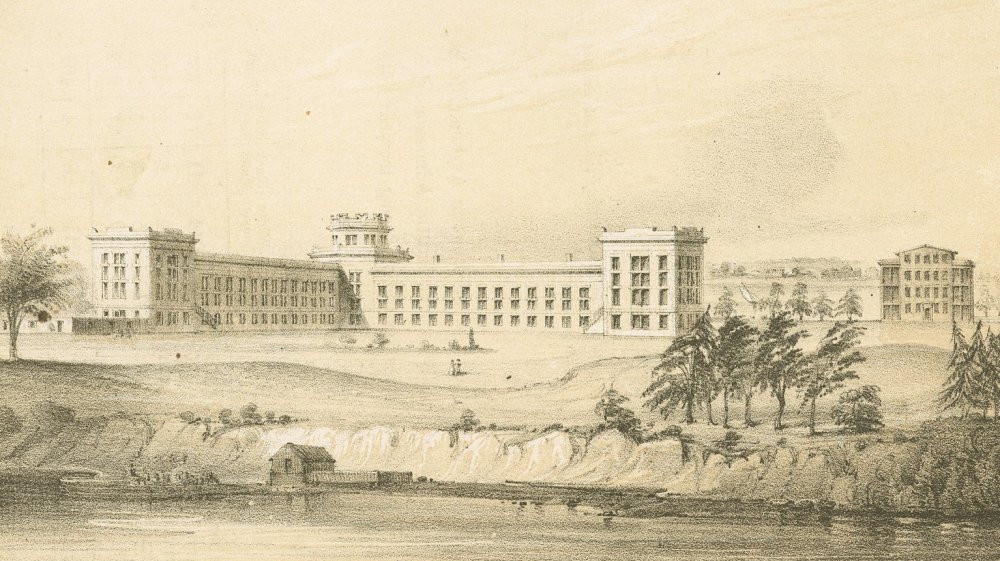

The second part of her plan commenced the next day, when she convinced a judge, several doctors, reporters, and the head of the insane pavilion at Bellevue Hospital that she was "undoubtedly insane" by faking amnesia. She was committed to the insane asylum (pictured above) on New York City's Blackwell's Island (now called Roosevelt Island). Once she was a patient, she was subjected to humiliating and inhumane treatment, beginning with a forced scrubbing in ice-cold water as soon as she passed through its walls.

Bly detailed the experience: "one after the other, three buckets of water over my head [...] into my eyes, my ears, my nose and my mouth. I think I experienced some of the sensations of a drowning person as they dragged me, gasping, shivering and quaking, from the tub. For once I did look insane, as they put me, dripping wet, into a short canton flannel slip, labelled across the extreme end in large black letters, 'Lunatic Asylum, B. I. H. 6.,'" via Brainpickings.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

For the next ten days, Bly was forced to endure terrible food, abysmal living conditions, and rude, unfeeling doctors and nurses. After listening to the stories of abuse and neglect from the other inmates and witnessing the deplorable conditions firsthand, Bly concluded, "What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment?" via New World Encyclopedia.

For the final step in her plan, the New York World's lawyers arranged her release from the asylum after ten days. However, even leaving was bittersweet, as Bly reported: "I had looked forward so eagerly to leaving the horrible place, yet when my release came and I knew that God's sunlight was to be free for me again, there was a certain pain in leaving. For ten days I had been one of them. Foolishly enough, it seemed intensely selfish to leave them to their sufferings. I felt a Quixotic desire to help them by sympathy and presence," per Brainpickings.

When her exposé, Ten Days in a Mad-House, was released in October 1887, Bly became an instant celebrity. Her reporting shone a harsh light on the brutal treatment endured by patients who had been sent to asylums ostensibly to be cured, and the public was scandalized. Bly herself proposed a series of reforms to improve the system. She assisted a grand jury in its investigation into conditions at the asylum, which led to an $850,000 increase in funds for the Department of Public Charities and Corrections to improve the treatment and conditions at asylums.

Nellie Bly went around the world in 72 days

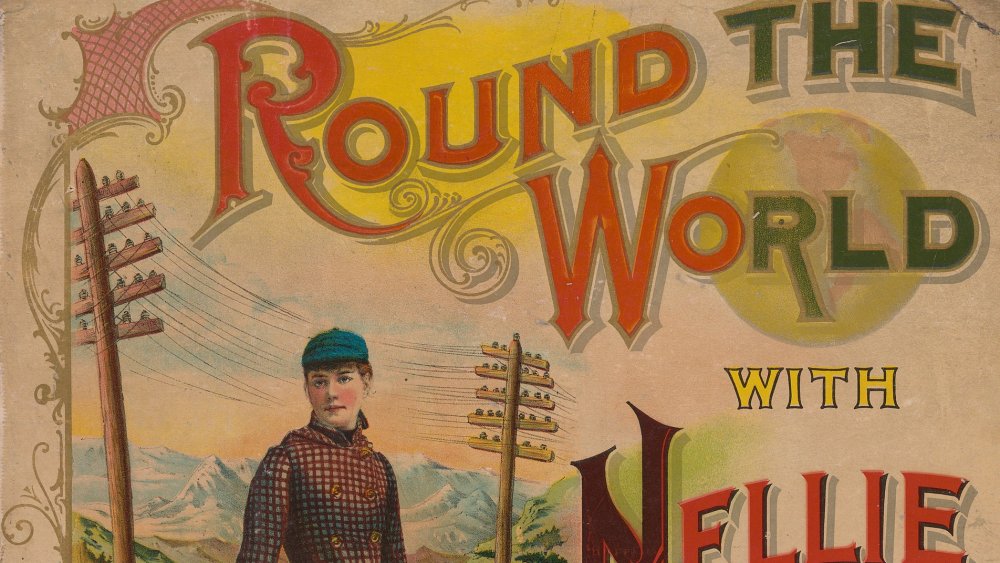

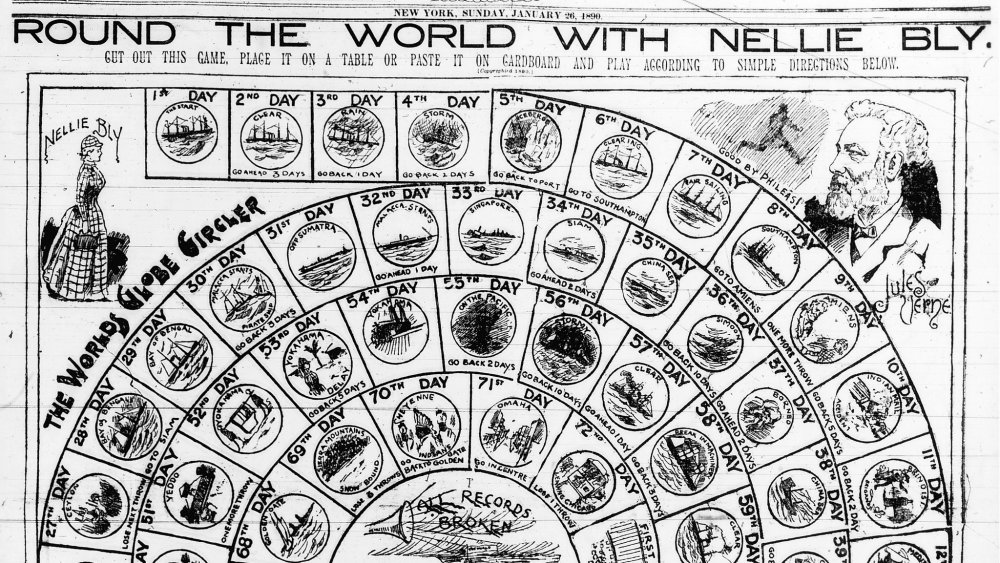

While her madhouse exposé may have gained her the spotlight, Nellie Bly's most famous stunt didn't occur until November 1889. Inspired by the famous Jules Verne novel Around the World in Eighty Days, Bly had proposed to her editor that she try to break the fictional record set by the book's protagonist, Phileas Fogg. At 9:40 AM on November 14, she boarded the steamer Augusta Victoria from Hoboken, New Jersey, and began her 24,899-mile journey around the world, sponsored by the New York World, according to New World Encyclopedia.

The trip generated worldwide press. The New York World generated even more excitement by publishing daily updates on her location. They even sponsored a guessing contest, in which they asked readers to guess, down to the second, when Bly would return and offering a free trip to Europe for the person with the closest guess. As the trip went on, Bly became an international celebrity. Games, songs, and even fashions were inspired by Bly and her famous journey, per Your Dictionary.

Bly completed most of the trip alone, traveling through Europe, Asia, the Suez Canal, and Ceylon via steamships, railroads, horses, rickshaws, and even a sampan. Along the way, she sent press releases and cables back home, reporting on her journey. Bly completed her trip around the world in 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes, and 14 seconds, according to Biography.

Nellie Bly had some friendly competition

During Nellie Bly's trip around the world, another reporter, Elizabeth Bisland, was hot on her heels. Hoping to capitalize on the worldwide attention garnered by Bly's trip around the world, Cosmopolitan magazine decided to sponsor their own reporter's trip, bragging that she could do it faster than both Bly and Verne's protagonist. Bisland began her journey in New York and started around the world in the opposite direction, planning to arrive back in New York before Bly reached Hoboken.

However, Bly had no interest in racing. In fact, she was unaware there was even a competition going on until she reached Hong Kong on December 25. She recounted meeting a man from the office of the Oriental and Occidental Steamship Company, who told her that she was at risk of losing the race. She recounted the exchange (via Smithsonian Magazine): "'Lose it? I don't understand. What do you mean?" I demanded, beginning to think he was mad. 'Aren't you having a race around the world?' he asked, as if he thought I was not Nellie Bly. 'Yes; quite right. I am running a race with Time,' I replied. 'Time? I don't think that's her name.'"

Bly completed her journey in Hoboken, the same place it began, on January 25, 1890, where she was greeted with crowds of cheering supporters. According to History, she had, in fact, beaten Bisland by four days, setting the world record at the time for the fastest trip around the globe.

The Iron Clad Manufacturing Company

At just 31 years old, the world-renowned journalist decided it was time to hang up her pen. In 1895, Nellie Bly married millionaire Robert Seaman, who was 73. He was the owner of a successful company, the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company, which manufactured steel containers. Bly decided to give up journalism to focus on caring for Seaman, who was in poor health, and assisting with his business.

Bly took over as head of the company following Seaman's death in 1903, per the National Women's History Museum. Ever resourceful, Bly had several innovative ideas and even received two patents for developing new containers. One patent was for an innovative milk can, and the other was for a new metal barrel design inspired by steel containers she saw while on a trip to Europe, according to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

However, inventive as she was, Bly had poor business sense. She held strong ideals about owners sharing profits with their employees, so she spent a good deal of her profits on amenities for her workers, including building a bowling alley, a clinic, and two libraries, per the Los Angeles Times. Her overspending was worsened by the fact that a factory manager was embezzling funds from the company. Bly's financial problems continued to worsen, and the company went bankrupt in 1911.

Nellie Bly reported from the front lines during World War I

Nellie Bly lost most of her money after the Iron Clad Manufacturing Company went bankrupt, so she returned, once again, to journalism. In 1912, she began writing for the New York Evening Journal. Two years later, World War I broke out, and Bly spent the next several years as a foreign correspondent, reporting on the war from the Eastern Front. She was the first woman to cover the war zone between Serbia and Austria-Hungary, where she was briefly arrested on suspicion of being a spy, according to New World Encyclopedia.

After the war ended, Bly returned to New York. She continued writing, covering social issues such as adoption, the women's suffrage movement, and capital punishment. She became an activist advocating for the rights of abandoned children and orphans in her later years and even adopted an orphan child herself at 57 years old, per ThoughtCo.

Her final job was working as an advice columnist for the Evening Journal, according to the Los Angeles Times. Nellie Bly died of pneumonia in New York on January 27, 1922.