The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Evita

Eva Perón, better-known as Evita ("little Eva"), is one of the most famous women of the 20th century in general, a near-mythical figure in her home country of Argentina. Rising up from humble beginnings, Evita made herself into one of the highest-paid actresses in Argentina before meeting and marrying Juan Perón just as he ascended to the pinnacle of power, becoming president of Argentina in 1946 and launching a political movement that continues to influence Argentinian politics today. Although her legacy is complex and controversial for many, she remains a symbol of both the country and a movement.

Evita's impact on the world was seismic, especially considering that she was a prominent part of politics and public life for just six years. Thanks to a lavish 1978 stage musical by Andrew Lloyd Weber, even people who have never paid any attention to Argentina or its politics know who Evita was and are familiar with the popular iconography that has grown up around her.

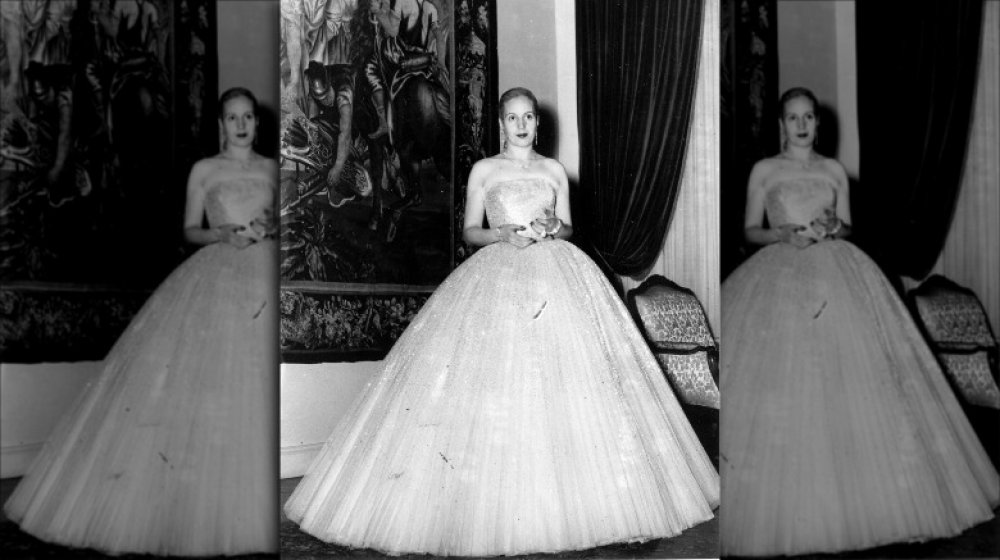

But Evita's brief life was filled with tragedy and pain which make her achievements even more impressive. The fact that she molded herself into an international icon in such a short time — she died when she was just 33 years old — is a testament to her talent for self-mythologizing and her peerless political instincts. But the tragic real-life story of Evita is more dramatic than you know.

Evita grew up poor

Born María Eva Duarte in Los Toldos, Argentina, Evita's childhood was impoverished and unstable. According to the Associated Press, her father was a wealthy man named Juan Duarte who had moved to the tiny, rural town to manage a ranch owned by his family. Her mother, Juana Ibarguren, took a job as a servant at the ranch and soon became Juan's mistress. At this time in Argentina, it wasn't unusual for wealthy men to have a second family, and for a time, things were stable.

Juan Duarte left Juana a year after Eva was born, however, and according to Encyclopedia Britannica, he died in a car accident when she was just six years old — which was also when young Evita learned that she was illegitimate and that her father had another family, one that was considered his "real" family. These events plunged the family into financial distress. As an unmarried woman with illegitimate children, Juana struggled, working tirelessly as a seamstress to support her children.

The image of her mother working to earn a living stayed with Evita. Years later when she was the most famous woman in Argentina, she used her charitable foundation to give away thousands of sewing machines to poor women.

Evita's father abandoned her family

Evita's mother, Juana, was only a teenager when she met Evita's father, Juan Duarte, but she quickly became Duarte's mistress and had several children by him, including Eva. According to authors Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro, Juana refused to act like a mere mistress. She took Duarte's name as if they were married and enjoyed a notorious reputation in the small village because she didn't act with the appropriate level of shame.

Duarte, for his part, encouraged this. He was, by all accounts, very kind and generous to his second family — until he decided to leave. Evita was just a year old when Juan Duarte left Los Toldos and his mistress, returning home to his wife and family in Chivilcoy. He apparently gave no reasons to Juana and left his second family literally nothing — no money, no means of support, and no legal standing. In the village, Juana was still reviled as a mistress. Rumors spread that she was sleeping with a long list of local men in exchange for food and support.

When Juan Duarte died a few years later in a car accident, Juana and the children were even denied the right to mourn him. They were barred from the funeral by his wife.

Evita was crushed when her grandmother died

María Eva Duarte was born into a poor and unstable family. Her mother had been the mistress of a wealthy man who abandoned her and his children shortly after Eva was born. This left them not just incredibly poor but also ostracized. As authors Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro note, her mother had to deal with the moralistic judgment of their small-town neighbors and was rumored to have slept with many men in their small village in exchange for money and support. And as The New York Times notes, her grandmother was also rumored to have supported the family in the same manner.

Those cruel rumors led the family to cling to each other and become extremely close. Eva's older brother Juan became their protector, getting into many fights when people insulted them. Experiencing such negativity and prejudice almost from birth, Eva was understandably an emotional child. She was prone to what Fraser and Navarro call "attacks of rage," and when her beloved grandmother died, she reportedly threw herself on the ground and cried "inconsolably." Evita's short life had already been marked by loss, and her childhood as an illegitimate child in a poor home shaped the political views that would have such an impact on the future of her country.

Evita tried to hide her past

When biographers began to put together the life story of Eva Perón, they discovered a curious thing: Her birth certificate appeared to have been falsified.

Evita was born poor in a tiny rural town, the illegitimate daughter of Juana Ibarguren and Juan Duarte. As the Associated Press reports, Evita was initially registered under her mother's last name because Duarte refused to accept official responsibility for the children he fathered with Juana, though he did support them for a time. Years later, when Evita was poised to marry Juan Perón and become one of the most famous and powerful women in the country, her illegitimate status was a problem. Argentina was a religious society, and a prominent politician couldn't be with a woman with a bad reputation.

As authors Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro report, in 1944, Evita's original birth certificate was still on file in her hometown of Los Toldos. In 1945, her sister visited the town clerk and tried to convince him it was in his best interests to alter the records, but he refused. Sometime in the next few months, however, the original birth certificate was destroyed, and a new one that showed her as the legitimate daughter of Juan Duarte was substituted. Twenty-six years after her birth, Evita had finally succeeded in erasing her shameful past.

Evita likely wanted children

Evita married Juan Perón in 1945 and remained married to him for the final six years of her life. Despite being the First Family of Argentina during most of this time, Evita and Juan never had children, nor is there any official record of a pregnancy. However, it's very likely that Evita wanted to have children but was unable to.

As author Jill Hedges writes, a woman named Nilda Quartucci claimed to be Evita's illegitimate daughter, born in 1940 when Evita was a struggling actress in Buenos Aires. Her claim has never been proven, but at the time, Evita discussed a "secret suffering" with a local priest named Hernán Benitez. Father Benitez later admitted that the young actress made an appointment to talk to him about something she might take "extreme measures" about, but he forgot to meet with her.

As Hedges reports, Evita expressed a desire for children when she married Perón but may have suffered a miscarriage as a result of her uterine problems — problems which developed into terminal cervical cancer just a few years later. This makes it very unlikely that Quartucci is her secret daughter — but very likely that Evita wanted to have children and could not. This becomes extra heartbreaking when you consider her work involving the poor children of Argentina.

Gossip about Evita was hurtful

Politics can be brutal. When combined with sexism, that brutality can reach epic proportions. As a beautiful woman in 1940s Argentina who seemed to rise up out of nowhere to become one of the most famous and influential people in the country, if not the world, it would be surprising if Evita didn't have enemies. And those enemies tried their best to spread malicious rumors about her, one of which was particularly hurtful: that she'd been a sex worker in Buenos Aires prior to meeting Juan Perón.

As Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro point out, in the 1940s in Argentina, it was still common to believe sex workers were manipulative women with secret powers of influence. As Evita gained prominence and enemies, it was easy to combine her obscure past with her sudden relationship with Juan and imply that she'd seduced him using her professional sexuality. As Julie Taylor notes, this idea gained so much credence that even Jorge Luis Borges, a respected literary figure in Argentina, accepted that Evita had been a "common prostitute" before marrying Juan Perón.

This was especially painful because Evita's mother and grandmother were both accused of sleeping with others for money when she was a child, solely because her mother was a "fallen woman" who'd had children outside of wedlock.

Evita suffered terribly from cervical cancer

As noted by Nicholas Fraser and Marysa Navarro, the first sign that Evita was ill came in early 1950, when she fainted while giving a speech. She was rushed to the hospital, and it was announced that her appendix had been removed and that she was recovering. In truth, she had developed cervical cancer at the age of 30 — but Evita was not informed of the diagnosis and continued to work a punishing schedule that left her visibly thin and exhausted.

While Evita was kept ignorant of her disease, Juan Perón and his government took steps in secret to try and treat her without revealing her cancer. When her pain and suffering became agonizing and doctors feared she'd soon be too weak for surgery, they tried to convince her to have a hysterectomy, but she refused, believing her political enemies simply wanted to remove her from public life. When Evita was finally convinced that the operation was necessary, Dr. George T. Pack, one of the leading oncologists at the time, was secretly flown in to perform the procedure. Evita never met Dr. Pack and did not know he performed the surgery.

As noted by author Darlene R. Stille, Evita's last public appearance was at her husband's second inauguration ceremony, during which she rode next to him in a car, waving at the adoring crowds. She was so weak and in so much pain that she had to wear a special brace under her clothes to remain upright.

Evita might have lived if she hadn't married Juan Perón

Evita's painful, early death from cervical cancer was tragic. At the height of her power, influence, and fame, she was felled by a terrible disease — one which might have been treatable, even in 1952. But not only was she never informed that she had cancer, but she didn't receive treatment until it was far too late.

Worse, as Medical Bag makes clear, she might not have developed the cancer at all if she hadn't married Juan Perón. As Dr. Roberto Leon explains, 99 percent of cervical cancers are caused by human papilloma virus (HPV), a venereal disease. Many people become infected with HPV over their lifetimes, but most fight it off without suffering any ill effects. Some men can pass it on to their partners, however, where it can cause cervical cancer.

Juan Perón's first wife, Aurelia Tizón, also died at a very young age of cervical cancer. As author Jill Hedges notes, her death was eerily similar to Evita's, marked by bleeding, pain, and terrible suffering. This makes it very likely that Perón was an unwitting carrier of HPV and infected both of his wives, dooming them to a painful death.

Juan Perón forced Evita to have a lobotomy

One of the most horrifying details of Evita's last days was secret until fairly recently. While her suffering while she slowly died of cervical cancer is well-documented, the BBC reported in 2015 that examinations of her remains had led medical researchers to believe she underwent a prefrontal lobotomy shortly before her death.

This isn't as crazy as it might initially sound. As The New York Times notes, lobotomies were once seen as an effective remedy for many ailments, including chronic pain and emotional distress. It's not impossible that Evita's doctors thought the brain surgery would reduce her suffering, or at least make it a little more bearable. But the physician who conducted the research, Dr. Daniel E Nijensohn, believes the procedure had a more nefarious goal: to control her increasingly irrational behavior during a hard-fought presidential campaign.

As the BBC notes, in her final months, Evita became increasingly violent in her speeches and had reportedly ordered a cache of weapons, which she intended to hand out to her supporters. This rhetoric and the arming of a private army could have led Argentina to a bitter civil war, and it's theorized that Evita's husband, President Juan Perón, might have ordered the lobotomy in order to control her better during the campaign.

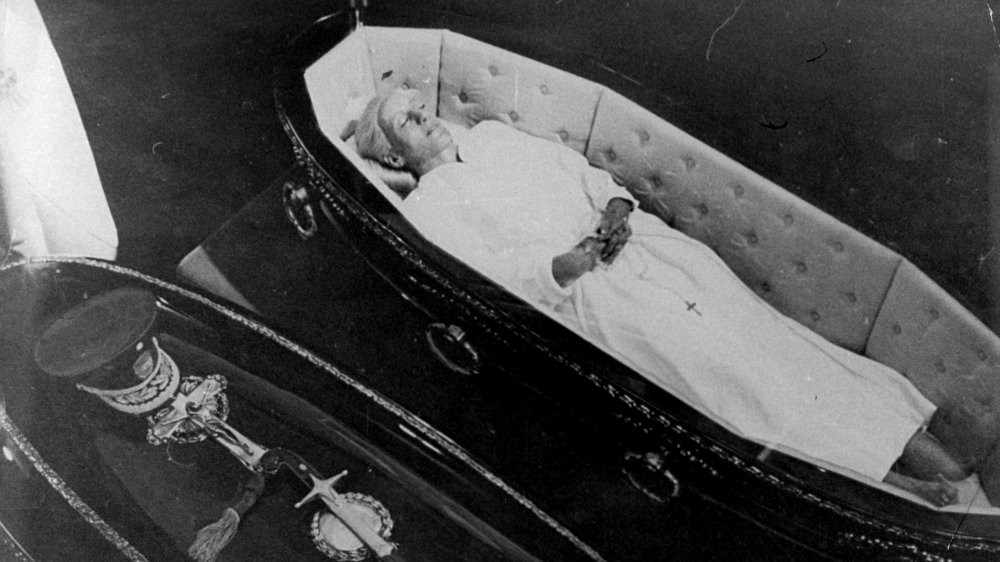

Evita's body was stolen

When Eva Perón died in 1952, she was an immensely important political figure in Argentina. While many in the rich upper classes and the military despised her and her husband, President Juan Perón, she was almost a saintly, religious figure to the poor and the working class, which is why, as The New York Times reports, when Juan Perón was overthrown in a violent coup in 1955, military officers took possession of her body and hid it away. They feared her corpse would be a focal point for the opposition, so they sought to remove this powerful symbol of what was known as "Perónism."

But as the BBC reports, the military government had a problem: No matter where they hid Evita's body, her supporters would find it and mark the site with flowers and other tributes. The military moved the body several times, but it kept happening. Eventually, they had Evita's remains shipped to Italy, where they were buried under a false name. Even then, trouble followed: In 1970 Perónist supporters kidnapped and assassinated former president General Pedro Aramburu because he'd overseen the theft of Evita's body.

Evita remained in Italy until 1971, when Perónism was legalized and she was returned to her husband. A few years after Perón's triumphant return to power in Argentina and his sudden death, Evita was finally returned to her home.

Evita's body may have been abused

Evita proved to be as powerful and controversial in death as she'd been in life. Three years after her death, her body was stolen and shipped to Italy in an attempt to remove a powerful symbol of what had become known as "Perónism." It remained there for 16 years.

Even worse than having your eternal rest interrupted for political purposes, it's possible that Evita's body had been abused badly at some point. As popular as she was with the working-class and poor people of Argentina, Evita also had a long list of enemies who despised her. It's possible some of them took out their anger on her body once it had been stolen.

According to the BBC, the man who was charged with restoring Evita's body to a presentable state before her return to Argentina in 1974, Domingo Tellechea, reported that her feet were badly deformed, probably from being hidden in a standing position for a lengthy period, that her body showed signs of having been compressed in a too-small coffin. Also, the remains had a wound and "marks on the outside of the body." Tellechea did remarkable work restoring Evita's remains so she could be put on public display. Her remains were finally laid to rest in Buenos Aires in 1976 — 21 years after they were stolen.

Evita's legacy is continually under attack

When she was alive and one of the most powerful people in Argentina, Eva Perón was subjected to many attacks on her morals and character — most commonly that she had been a sex worker before marrying Juan Perón. Her politics were controversial and became even more so during the years when Argentina was wracked by revolution and military dictatorship. Evita remains a powerful symbol, and thus, her legacy remains under constant attack.

One of the most potent is that Evita was a Nazi sympathizer who profited from the Holocaust, accepting gifts of treasure stolen from Jewish people in the concentration camps. As The Guardian notes, it's true that Argentina became a safe haven for Nazi war criminals in the aftermath of World War II. As author John Barnes notes, Argentina was in a powerful economic position because of the war-torn world's need for food, and Juan Perón was able to ignore even the United States when they demanded that war criminals be extradited. Argentina hoped Nazi scientists and technicians could contribute to the Argentinian economy.

But as The Washington Post reports, quoting historian Marysa Navarro, there's no evidence that Evita was directly involved with the policy that welcomed Nazis such as Adolf Eichmann (pictured above) or that she received any "treasures." The bottom line is that while there's little doubt that Juan Perón was a Nazi sympathizer, there's little evidence that Evita shared his feelings.