The Phoenicians: Who Were They?

The world of the ancient Mediterranean was pretty crowded. According to the Ancient HIstory Encyclopedia, the Mediterranean Sea of 2000 BCE was already ringed with prosperous settlements and crisscrossed by intrepid sailors. The land and ocean alike were rich with natural resources, from minerals, to timber, to agriculture, to seafood.

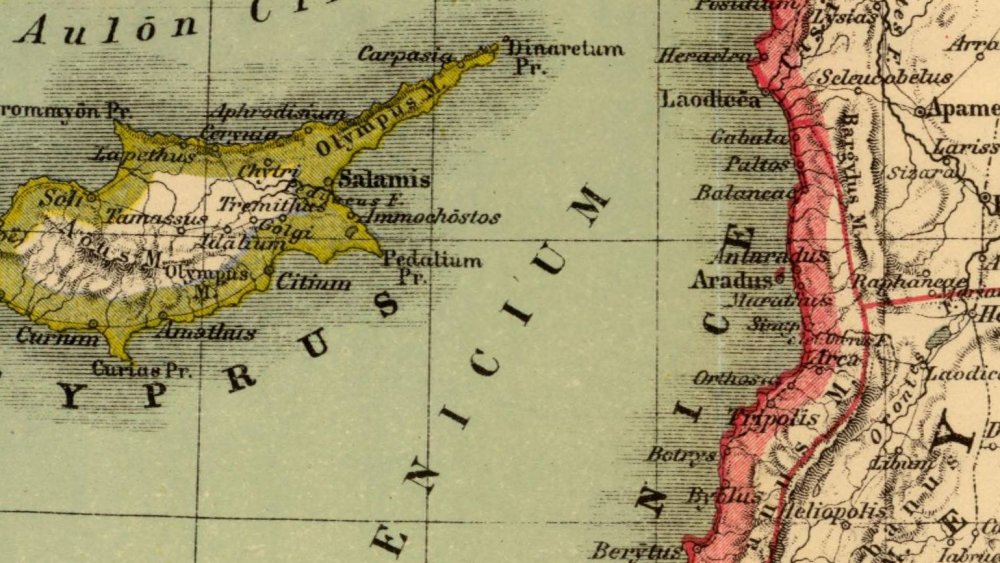

At the heart of it all were a mysterious people: the Phoenicians. Even today, historians and archaeologists can't quite agree on who was a part of this diverse group. Per The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Phoenician people were most active around 1500 — 300 BCE and lived in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean. They became renowned as traders and city-builders, establishing major centers like Tyre, Byblos, and Sidon. Yet, most of our sources concerning the Phoenicians come from outsiders like the Greeks. In fact, it looks as if the Greeks coined the name "Phoenicia" to describe these traders, from "phoinix." There's still some mystery here, since, according to Who Were the Phoenicians?, the origins of the Greek name are also unclear.

What is clear, however, is that the Phoenicians were mighty. They established cities that are described in the Bible, created impressive artworks that survive to the present day, and maybe even sailed as far as the British Isles. The mysteries of their past add interest to an already fascinating and complex history.

The Phoenicians weren't a nation

The Phoenicians did not exist. Well, at least not as "Phoenicians."

Instead, says The History and Archaeology of Phoenicia, this was a description used by the Greeks to describe a loose federation of traders from the eastern Mediterranean. We'll keep using the term for convenience's sake, but keep this fact in mind if you ever take a time machine back to the Bronze Age Levant region. If you ask for directions to Phoenicia, you'll confuse practically everyone.

Instead of coming together as one great, cohesive nation, the people we now call Phoenicians actually lived in and around independent city-states. According to Haaretz, these included settlements like Byblos and Tyre, mentioned in the Old and New Testaments. In fact, Byblos was such a big deal that its name is actually the origin of the word "Bible," reports Britannica.

Thanks to all of this confusion, tracking down the Phoenicians has proven to be pretty tough. They left behind very few written records, apart from boilerplate temple dedications that don't give us much new information. Many of our sources describing them come from outsiders like Hebrew, Greek, and Roman authors, says The Jewish Quarterly Review.

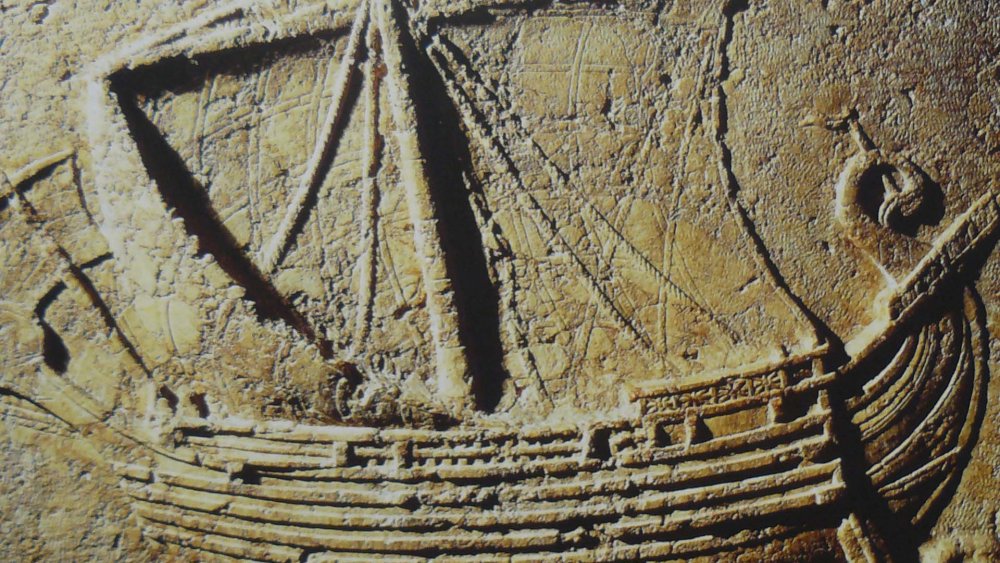

The Phoenicians were master sailors and shipbuilders

If the Phoenicians were known for anything in the ancient world, it was their mastery of the ocean. They were so good at it that even their earliest colonial overlords acknowledged the strength of their craft.

During the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, which covered 2575 to 2150 BCE, the city of Byblos was under Egyptian control. That allowed pharaohs and other high-ranking Egyptians to enjoy exotic goods like cedar and fir wood, says The History of Phoenicia. Thanks to the demand for timber and other goods, the port of Byblos was one of the busiest, most important shipping centers in the region.

If the Phoenicians were so good at transporting goods, then it stands that they also had to be highly skilled sailors and shipbuilders. Ancient Egyptian sources, like those referenced in Early Dynastic Egypt, refer to "Byblos ships" as the premiere vessels for oceangoing trips. These ships would have also been larger and faster than many other seafaring options. The Ancient Egyptians stood to make a lot of money thanks to their control of Phoenician lands and technology.

Some called the Phoenicians pirates out of jealousy

Phoenicians pop up in Homer's Odyssey, one of the most famous works of ancient literature. However, they aren't always depicted in the best light. Some of the references there, says On Art in the Ancient Near East, are pretty complementary. The Greek characters praise luxury goods produced by the Phoenicians, like a silver mixing bowl given to Telemachus, the son of Odysseus, toward the beginning of the epic poem.

On other occasions, however, Homer hints at the Phoenicians' less than stellar reputation. In one scene, Odysseus listens to the tale of old Eumaeus, who says that he first came to Ithaca after being kidnapped by a Phoenician pirate crew. Eumaeus says that the Phoenicians were "greedy knaves." Though we know the Odyssey is fiction, Homer could be describing some very real Greek prejudices.

Where did this all come from? It might be the result of jealousy, says the American Journal of Archaeology. Traditionally, scholars have said that the Ancient Greeks were especially harsh against the Phoenicians because the Greeks were only occasional traders, thinking it beneath their dignity. Meanwhile, the Phoenicians took trading on as an icky full-time job. They also dared to be good at it. That might not capture the whole picture. The journal Ancient Society argues that Homer might not have been all that down on the Phoenicians. He could have simply been ill-informed and maybe a bit too eager to work some cool pirates into his tale.

The Phoenician alphabet is at the heart of writing

In The History, the ancient historian Herodotus said that the Phoenicians taught the Greeks their alphabet. Herodotus, who also hinted that maybe Zeus is real and had never heard of a peer-reviewed journal, isn't exactly the epitome of academic integrity. That said, he may have been onto something in this passage. The Phoenician alphabet could actually be at the heart of many writing systems we still use today.

To be clear, the Phoenicians definitely didn't develop the concept of an alphabet on their own. According to History, that honor probably goes to Semitic people who riffed on Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs around 2000 BCE. It looks as if the Phoenicians, who would have been closely related to these groups, then took that writing system and made it their own.

The special Phoenician innovation was spreading this alphabet through their trade routes, says The History and Archaeology of Phoenicia. Inscriptions using this writing system pop up all throughout the regions where they settled. Eventually, the Greeks made their own variation on the alphabet, giving vowels just as much importance as consonants. This established a writing convention that would go on to influence Latin and many modern languages.

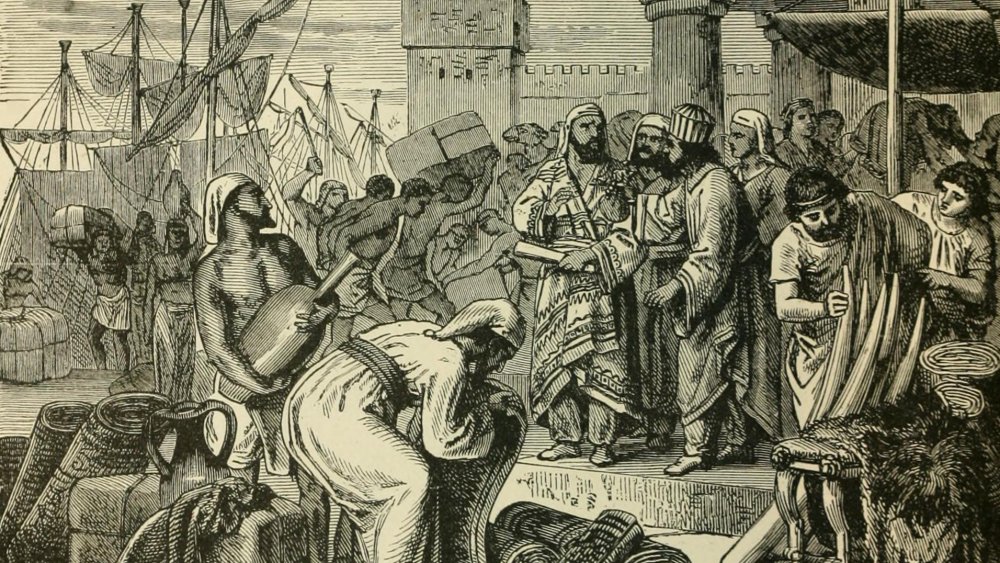

If you traded, it was with the Phoenicians

Thanks to their seafaring prowess and unique goods, the Phoenicians became well-known traders, says the Ancient History Encyclopedia. They had connections to the Greek islands, Africa, parts of Europe, and maybe even ancient Britain. A few land routes supplied other goods from as far afield as India.

They were savvy businesspeople, often taking low-value goods from one part of the world and selling them at a significant markup in other regions. Tin mined in Iberia and beyond, says Expedition Magazine, wasn't especially valued by the people living there. However, it could be sold for a healthy sum in other parts of the Phoenician trading realm.

Rather than act exclusively as middlemen, Phoenician people also produced their own goods, says Britannica. They exported cedar and fir wood that made the region famous for its timber. At the same time, they crafted finely made textiles, like linen woven in Tyre and embroidery from Sidon. Unfortunately, cloth doesn't survive millennia very well, but the Phoenicians weren't stopping there. Per the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, they also earned a reputation as skilled artisans working with metal, glass, and clay.

The Phoenicians are in the Bible

For many people, their first encounter with the Phoenicians comes through the Bible. They aren't exactly named that in the pages of the book, thanks to historical confusion over the identity of Phoenicia, but they are definitely there, says The Metropolitan Museum of Art. You can identify them through their cities, like Byblos, Tyre, and Sidon.

In the works of ancient Jewish historian Josephus, Israel's King Solomon is said to have teamed up with King Hiram of Tyre on some very plum trade deals. He even commissioned Phoenician masons to shape the foundation of the Temple in Jerusalem. In return for Hiram's generosity, says the Biblical book of 1 Kings, Solomon sent a regular gift of food for the Tyrian royal household. Hiram appears to have been savvy in the ways of trade relations. Earlier, in 2 Samuel, Hiram had already made nice with the legendary King David by sending cedar logs and stonemasons to set up a sweet new palace for the ruler.

The Bible also records some of the tragedy that hit the Phoenicians and the rest of the Mediterranean. Ezekiel 27 contains a lament for Tyre, listing the wonderful goods that made it famous. Its glory didn't last forever. After a punishing 13-year siege by King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon, says the Ancient History Encyclopedia, it was no more. In the words of Ezekiel, speaking to the city, "You have come to a horrible end and will be no more."

Phoenicians pop up in Greek mythology

Despite an unwillingness to write about themselves, the Phoenicians keep showing up in other records throughout the ancient world, including Greek myth.

Europa is arguably one of the best-known Phoenicians in ancient mythology. According to Britannica, she was the daughter of King Agenor of Phoenicia. She was also famously beautiful, to the point where Zeus, king of the gods, took notice. When Zeus starts paying attention to a mortal, weird and awful things start happening. In the case of Europa, Zeus turned himself into a white bull and carried her away to the island of Crete. She eventually had three sons by the god, including King Minos.

When Europa disappeared, says The Oxford Classical Dictionary, her family didn't take it sitting down. Agenor sent her brothers, Phoenix, Cilix, and Cadmus, to the rescue. Given that they were facing Zeus, who could throw lightning and turn into amorous animals at will, they didn't stand a chance.

The brothers did survive their anti-Zeus quest, at least. As related by Britannica, the defeated Cadmus went to an oracle for advice. He was told to follow a cow and build a town wherever the animal stopped. He followed the odd advice and eventually founded Thebes. In the meantime, Cadmus killed a dragon and buried its teeth. Violent, warlike men sprang up from the same ground and, after they finished fighting one another, helped build Cadmus' brand-new city.

The Phoenician religion has some familiar figures

Like many people of the time, the Phoenicians practiced a polytheisic faith with many different gods. The names and stories of those goddesses and gods trickled down into other cultures and stories, thanks to the far-traveling Phoenician people. One such figure was the widely known Baal. He was worshiped throughout the Middle East, says Britannica, especially by the Canaanite people in what's now parts of Israel, Palestine, and Lebanon.

Many historians argue that the Phoenicians and Canaanites were likely one and the same. If nothing else, clues indicate that they were very closely related. For both the Phoenicians and Canaanites, Baal was a storm god. He was sometimes called "Baal Shamen," or "Lord of the Heavens," among many other names recorded by The American Journal of Philology.

Other gods populated their world, says the Ancient History Encyclopedia, like Adonis, El, and Astarte. The term "El" could refer to an individual god or a general deity, but it gets extra interesting when you pay attention to the parallels between the Phoenician El and the Yahweh of the Old Testament. The Oxford Companion to World Mythology states that there's a pretty clear connection between the Canaanite god and the one that later showed up in the Bible.

The Phoenicians have been used to back up nationalist causes

From Lebanon to Ireland, different people have used supposed Phoenician heritage to bolster their cases for independence and cultural heritage.

Some of the first people outside of the Mediterranean to claim Phoenician heritage were British, says Aeon. Sixteenth-century writers like John Twyne said that the far-ranging Phoenicians were the first foreigners to land on their coasts. He also wrote that the original inhabitants of Britain were gigantic descendants of Neptune, the god of the sea, so remember to take his theories with a healthy grain of salt.

At roughly the same time, Irish nationalists were also trying to establish Phoenician ancestry. Ogygia: Or, A Chronological Account of Irish Events, published by Roderic O'Flaherty in 1685, champions this idea. Eighteenth-century scholar Charles Vallancey pushed for the same based on what he thought were similarities between the Irish gaelic and Phoenician languages, says The European Legacy. Most modern researchers can't ignore the inaccuracies in their work and no longer take it seriously.

At least Lebanon's nationalist movement, called "Phoenicianism," had the benefit of geography. Contemporary sources do say that the Phoenicians came from the same Levant region that includes modern Lebanon. According to Middle Eastern Studies, this 20th-century campaign was first pushed by Lebanese Christians who wanted to distinguish themselves from their Muslim neighbors. Given how much "Phoenicia" has been constructed by people from Ancient Greece to modern Lebanon, we may never know the truth of their descendants.

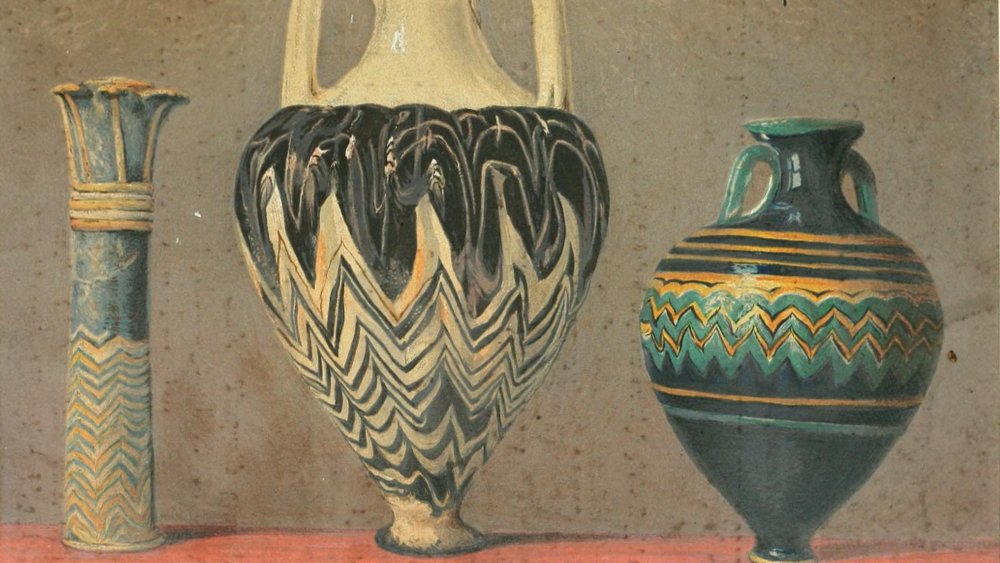

The Phoenicians' unique artistic style mingled different traditions

While Phoenicians were arguably best known for their trade networks and immense seafaring skill, that's not all there was to their culture. Today, most historians and archaeologists agree that they developed a unique and distinct artistic style thousands of years ago.

According to A Brief History of Entrepreneurship, Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote down a legend that says Phoenician sailors accidentally invented glass. Landing at night, they built a fire on a beach, which then effectively melted the sand. There's no evidence to back up this story, but it's clear that the people in various Phoenician cities became highly skilled glassmakers. Even today, glassmakers in Malta, a former Phoenician colony, claim to carry on millennia-old techniques from the ancient masters.

The Phoenicians were no slouches when it came to other crafts, says The History of Phoenicia. Taking cues from other art traditions in the region, like those of the Egyptians and Greeks, they became well-known for their works in ivory and metal. Even passages in the Bible, like Ezekiel 27, focus on the beautiful work produced by artisans in the city of Tyre. Too bad that textiles and carvings are notoriously short-lived and don't generally survive for thousands of years.

The Phoenicians may have sailed as far as Britain

While some have claimed Phoenician heritage in order to bolster nationalist claims, evidence for Phoenician ancestry is pretty hard to prove. After all, there was no distinct Phoenician nation but rather a loose collection of cities and settlements that encompassed a diverse group of people. Yet, there is tantalizing evidence that Phoenician traders really did sail as far as the British Isles in ancient times.

Genetic testing has shown that they at least made it as far as Portugal, reports The Independent. In 2016, scientists isolated a rare DNA sequence from a young man who died around 2,500 years ago in ancient Carthage, now in modern-day Tunisia. That same genetic code has been found in a modern-day person living in Portugal. Thanks probably to an amorous Phoenician sailor, we now have pretty strong evidence supporting the existence of their far-reaching trade network.

Did they go even farther? The Metropolitan Museum of Art mentions that the Phoenicians could have sailed beyond the Strait of Gibraltar, which connects the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Ocean. We have good evidence that they traded in tin, though we don't know if it came from Britain or closer to home. While it's not a smoking gun, some researchers wonder if the Phoenicians, who were clearly comfortable with the open ocean and invested in trade, might have sailed all the way up to British waters in search of a good deal.

The Phoenicians got rich thanks to special snails

Maybe more than anything else, what really cemented the Phoenicians in history was their involvement with a carnivorous sea snail. The Murex snail is a group of relatively large carnivorous snails that thrive in tropical seas. They were first mentioned by Aristotle in The History of Animals, making "Murex" one of the oldest scientific names still in use today.

The Phoenicians are generally credited with the technological innovation of turning these oceangoing gastropods into purple dye, says The History of Phoenicia. It turned out that the two most common Murex species in their area created a rich purple dye that resisted fading. The only catch was that the extraction process was agonizingly long and involved fermenting the crushed snails. The stink was reportedly so bad that dye processing operations were set up far away from peoples' homes.

The difficulty of producing the purple also meant that it was incredibly expensive. According to the BBC, Tyrian purple, so named after the Phoenician city of Tyre, was so precious that it was soon reserved for royalty only. The purple even makes appearances in much later artworks, such as the purple drapery worn by Christ in Michelangelo's The Last Judgement.